Michael Fitzpatrick

LM network resources

|

Dr Michael Fitzpatrick recently retired after over 25 years as a GP in Barton House Health Centre, Stoke Newington, London[1]. He trained at Oxford and the Middlesex Hospital [2]. Fitzpatrick was a leading member of the now defunct Revolutionary Communist Party and is an associate of the libertarian anti-environmental LM network having been involved with Spiked, Global Futures, Sense About Science, the Risk of Freedom Briefings, Worldbytes and the Battle of Ideas. From 2001 to the present he wrote for Spiked as the health correspondent. In May 2010 he became, and continues to be, a trustee of the lobby group Sense About Science having accepted an approach from Tracey Brown[3]. His writing has also been listed as suggested reading for the Battle of Ideas events since 2005, where he has appeared every year, on 17 panels as of 10th December 2014, including a number of discussion topics, often related to alcohol and drug use. He contributed regularly to the British Journal of General Practice between 2002-2012, Community Care from 2007-2011, and between 2003-2004 he had a regular column in The Lancet, for whom he contributed 31 articles in this period, contributing one further article in 2007.

Contents

Links with the LM Network

Michael Fitzpatrick, like his brother John, was a leading member of the RCP. He frequently contributed to its monthly review Living Marxism under the alias Mike Freeman. Living Marxism later became LM, in which Fitzpatrick had a regular column. Fitzpatrick has since contributed regularly to Spiked [4] and has spoken at events organised by both Spiked and the Institute of Ideas (IoI), such as its Genes & Society Festival, organised in association with Pfizer. Spiked and IoI both developed out of LM. Fitzpatrick has also contributed to the work of the Progress Educational Trust,[5] another body with links to the LM network.

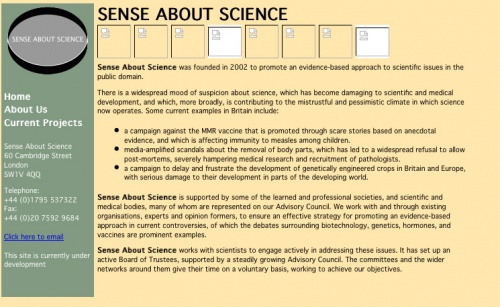

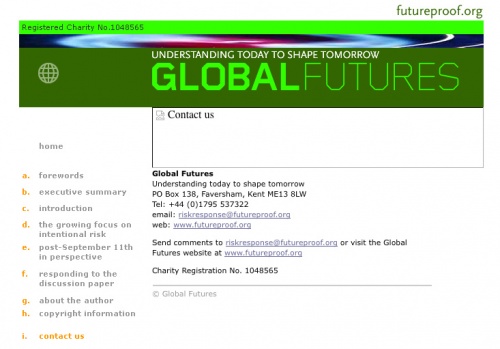

Since May 2010 he has been a Trustee of the controversial lobby group Sense About Science.[6] Sense About Science shares its telephone number with an organisation called Global Futures of which Fitzpatrick is also a Trustee and to which Sense about Science's director, Tracey Brown, and its assistant director, Ellen Raphael, also belonged, prior to its seeming demise.[7] [8][9][10]

Tracey Brown and Ellen Raphael both contributed to the magazine LM, which developed out of the monthly review of the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP), Living Marxism. Global Futures appears to be one of a series of front groups generated by the political network of individuals involved with LM and the RCP to forward their political agenda.

He was also member of the the joint Forum of the Social Issues Research Centre (which regularly donated to Sense About Science between 2003 and 2007[11]), for whom he was a contributor to the formulation of 'Guidelines on Science and Health communication for the media'. He is also a member of the Royal Institution which drew up the Guidelines on Science and Health to try and 'improve' the reporting of controversial scientific issues like GM foods by the media. Other members of the Forum included Professor Sir John Krebs FRS, the chairman of the Food Standards Agency, Lord Dick Taverne QC, the Co-Directors of The Social Issues Research Centre, and Baroness Susan Greenfield, former Director of The Royal Institution.

MMR

Fitzpatrick led the Medical Research Council team that concluded in 1998 that there was no risk from the MMR vaccine after Dr Andrew Wakefield claimed that patients had suffered adverse reactions from it. In a 2004 paper published in the British Medical Bulletin Fitzpatrick argues

The unfolding of the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) controversy reveals some of the key features of the cultural climate affecting matters of health and illness in contemporary society. A high level of anxiety around issues of health is reflected in a heightened sense of individual vulnerability to environmental dangers (such as atmospheric pollution, electromagnetic fields, bioterrorism) and in a general aversion to risk, particularly in relation to children. This mood has proved responsive to views sceptical, if not hostile, towards science and medicine and associated professionals, particularly in the sphere of immunization[12]

The case itself caused much controversy and Wakefield, who now lives in the USA, continues to stand by his research and deny all allegations against him. His supporters, mostly parents of autistic children, maintain he is the victim of a conspiracy and witch-hunt.[13]Martin J. Walker provides a detailed description of the controversy surrounding Fitzpatrick's involvement in the case and questions whether his roles for Global Futures and Sense About Science, who are both heavily funded by a number of pharmaceutical companies (including the 3 main producers of vaccines), may have had an influence on his research[14].

Views

Many of his articles centre on the belief that all relationships with state institutions are negative, and a vague notion of ‘people know what is best for themselves’, should rule. He has questioned the value of health programmes expanded by the government encouraging the ‘five a day concept’ through the change4life programme and argues it is used as a mechanism to increase the relationship between the state and people’s personal lives, as a result of loss of state authority in other areas.[15]. He also talks disparagingly about programmes which involve the offering of advice around sexual health issues in a number of articles and strangely takes the position that feminists should not have sought for law enforcement agencies to become involved in domestic violence cases because they (law enforcement) exist as representatives of a patriarchal state. He also sees attempts to encourage GPs to take a proactive approach towards achieving disclosure of domestic violence as 'insidious' and ‘means opening up the personal realm of family life and relationships to professional interference on an unprecedented scale’[16]. Fitzpatrick has also described alcohol, tobacco, chemicals, cars, fast food and pharmaceuticals as ‘stigmatised products’[17] and was frequently cited in the media regarding the Andrew Wakefield MMR-Autism scandal. He has written numerous articles on autism for Spiked, as well as two books, one entitled 'Defeating Autism: a damaging delusion' (Routledge, 2008), which followed from 'MMR and Autism: what parents need to know' (Routledge, 2004).

Writing for Living Marxism/LM (1990-2000)

Fitzpatrick wrote for LM from January 1990 until April 2000, contributing close to 70 articles in this time. He takes a fairly consistent line of argument to a variety of issues, such as Aids, public health, smoking, and BSE amongst others. This often involves describing society as risk averse and quick to panic, arguing either that there is an an orthodoxy that restricts debate on the reality of certain risks, or that 'interested parties' seek to elevate certain forms of risk for their own benefit. These situations are then said to have led to a paralysing application of the precautionary principle which attacks the human spirit.

Aids

Many of Fitzpatrick's articles on Aids question the risk the virus poses in the UK, particularly to those understood to be in 'low-risk' groups. He argues the real motive behind health campaigns warning the public of the dangers of Aids was a moral crusade to encourage 'sexual conformity' and to pursue a 'moralist agenda'[18]. He also argues that in 'low risk' groups all forms of sexual activity can be practised and there is no need to practice 'safe sex' for the majority of heterosexuals in the UK, unless having sex with 'high-risk' partners. Fitzpatrick's analysis appears to relate to his disdain for any form of advice, which he appears to see as damaging to the human spirit and an attack on individual freedom.

Creating panic/Managing risk

For example, Fitzpatrick argues that the authorities have sought to exagerate the threat posed by Aids through 'propaganda':

The danger of an imminent and large-scale heterosexual epidemic of Aids in Britain has been the central theme of the vast wave of Aids propaganda that has engulfed British society since 1986.[19]

He has also argued this risk has been exagerated by the 'Aids establishment' in order to ensure public concern for the issue has remained prevalent:

The more senior figures in the Aids establishment... were concerned that the limited spread of HIV infection in the West Midlands was undermining their efforts to maintain a high level of public concern around the issue.[20]

A Moral agenda

Fitzpatrick argues that government campaigns on Aids were an attempt to deflect attention from economic recession and a mechanism to control people's personal lives:

The government's Aids panic is not a public health campaign at all, but a moral crusade. It is a means of promoting sexual and moral conformity by manipulating public fears about a rare but fatal disease. At a time of economic recession and social crisis, conventional morality and traditional family values provide a much-needed source of cohesion and stability. Aids has provided the most effective vehicle for the drive to restore Victorian values in the Britain of Mrs Thatcher and her successors. The breadth and depth of the consensus around 'safe sex', even when its irrationality has been exposed, is a testimony to the fact that for the government the Aids panic is worth every penny spent on it[21]

Aids and the Precautionary Principle

He also seems to equate campaigns promoting safe sex and warning about the spread of heterosexual Aids (which he describes as the 'aids panic') with an excessive application of the precautionary principle:

The Aids panic is now sustained by the argument that 'we don't know what might happen in the future, but we can't be too careful'. According to this logic, everybody should stay at home in case they get run over by a bus, or perhaps, you never know, hit by a meteor[22]

Aids Orthodoxy

Fitzpatrick argues an Aids orthodoxy has developed which seeks to stifle alternative debate, citing research questioning the links between HIV and Aids. However, whilst he acknowledges that the scientific merits of the alternative research he cites may well be debatable, he strangely still argues this example demonstrates an irrational aids orthodoxy:

Another challenge to the prevailing Aids orthodoxy comes from professor Peter Duesberg and other scientists who assembled for an 'alternative' Aids conference in Amsterdam last month. Duesberg refutes the view that HIV is the cause of Aids, emphasising the role of recreational drugs such as poppers and crack. Others at Amsterdam accepted that HIV plays some role in the genesis of Aids, but only in association with 'cofactors' such as other infections. They were, however, united in condemning the transformation of the HIV/Aids hypothesis into a dogma, the censorship and distortion of alternative theories and the suppression of funding for research into such alternatives. Whatever the scientific merits of Duesberg's case, which are certainly debatable, there can be no doubt that he has exposed the climate of irrationality that surrounds the whole issue.[23]

Public Health

Fitzpatrick took a similar line of argument to other 'healthcare issues' when writing for Living Marxism/LM, often rejecting any attempts to introduce proactive/interventionist approaches to healthcare, which he sees as invading people's personal spheres.

Domestic violence

For example, Fitzpatrick argued against interventionist approaches from GP's in the area of domestic violence, even when they have been shown to be effective at reducing incidences of domestic violence, arguing such policies equated to regulating people's behaviour rather than treating illness:

The long-term consequence of GPs adopting a more proactive approach to domestic violence is more insidious. It means opening up the personal realm of family life and relationships to professional interference on an unprecedented scale...A popular model, featured prominently in the BMA report, is the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project in Minnesota in America. This seeks, through multiagency working, to transform a range of violent behaviour into non-violent or egalitarian behaviour, showing respect and trust, giving support, being honest and accountable, fairly negotiating, taking shared responsibility, having economic partnership and responsible parenting. Whether or not this approach is effective in terms of deterring domestic violence, it carries the heavy cost of opening up the private sphere to public scrutiny and regulation in a way that is characteristic of authoritarian societies. Such an intrusion into people's intimate life can only be profoundly damaging both for the individual and for society[24]

The precautionary principle and Child protection

Similarly, Fitzpatrick is disparaging towards preventative strategies involving families, and the idea of promoting 'good parenting'. He also apppears to reject the idea of monitoring for child abuse as overly authoritarian:

Doctors are also expected to participate in the machinery of surveillance and intervention that has developed under the rubric of 'child protection'. This means maintaining constant vigilance for signs of abuse or neglect and keeping in close contact with local agencies, including social services and the police. Because, according to Labour front-benchers Jack Straw and Janet Anderson, as people accept that in extreme cases it is justified to intervene to remove children from their families, then it should also be acceptable to intervene at an earlier stage with a preventive strategy ('Parenting: a discussion paper', November 1996). For New Labour, preventing what it considers is an automatic transition from poor parenting, to juvenile delinquency, to a life of crime, justifies interference in every family in the country.[25]

He also criticises organisations which offer 'advice services' as, for Fitzpatrick, the act of asking for advice can only reinforce the feelings of inadequacy that lead one to ask for advice in the first place, further undermining self-confidence:

The intrusion of an external source of authority into the family undermines not only confidence, but accountability. This is the effect of help lines such as ChildLine and Parentline...Originally motivated by a concern to expose child abuse, such agencies find themselves dealing with a wide range of day to day family conflicts, in which they act as a sort of conciliation and arbitration service. As a result, children are indulged, adults degraded and parental authority weakened.[26]

Obesity

Writing on issues surrounding healthy living, Fitzpatrick questioned the validity of evidence linking obesity and ill-health, particularly amongst those with lower levels of obesity. He also argues campaigns which seek to encourage weight loss provide a useful theoretical justification for imposing controls on everyone in society:

Linking weight to health makes it possible to generalise a sense of risk to the whole population. If more than half the population - including even me - is defined as being overweight, this surely justifies mass campaigns to change people's behaviour in the name of health. A major investigation of links between lifestyle and heart disease last year concluded that 'nearly everyone would benefit from being a little thinner' (British Medical Journal, 2 May 1997). In this way the influence of health professionals is extended from the sick to the well, and it becomes clear that the obsession with obesity provides a mechanism for imposing discipline over the whole of society.[27]

Smoking

Anti-tobacco moralism

In one article Fitzpatrick takes the line of argument that the turn towards greater regulation of tobacco in the 1990s reflected broader themes in society which assume individuals are weak, place too much significance on the power of advertising, and in which people refuse to take personal responsibility for their actions. He also suggests that an emphasis on the addictive qualities of nicotine is somehow indicative of this, rather than a scientific reality:

The political significance of the anti-tobacco crusade is that it resonates with some of the most influential themes in Western society today. It projects an image of the general public as helpless dupes of tobacco propaganda and as pathetic victims of chemical dependency on nicotine. The campaign against tobacco assumes a society of feeble individuals who need to be protected against cigarette adverts and against their own addictive personalities...The new emphasis on nicotine as an addictive drug, a key theme in the current US controversy, reinforces the notion of the vulnerable individual and further undermines the idea of individual responsibility for behaviour.

Passive smoking Orthodoxy

As with the issues of obesity and Aids, Fitzpatrick develops a line of argument which suggests an unscientific orthodoxy has developed around the impacts of passive smoking, citing a paper published by the Social Affairs Unit to back up his argument that this risk is exaggerated[29].

According to a recent Guardian editorial, 'mention of "passive smoking" now attracts groans and ridicule only from a small minority of those refusing to believe the overwhelming weight of opinion' (11 April 1996). It proceeds to invoke a consensus that embraces 'everyone else from the Department of Health to independent researchers' who accept that passive smoking damages health. Such a smug and rhetorical statement, typical of much public health propaganda, should immediately raise suspicion. In fact, much of the case against passive smoking is based on a statistical fallacy: the confusion of relative and absolute risk...(For a rigorous critique see JR Johnstone, 'Scientific fact or scientific self-delusion: passive smoking, exercise and the new puritanism' in Health, Lifestyle and the Environment: countering the Panic, Social Affairs Unit/Manhattan Institute, 1991.)[30]

In a somewhat 'tongue in cheek' piece Fitzpatrick suggests the drive to ban smoking in public places has not gone far enough and links such policies to Pol Pot's Killing Fields and the Nazi's 'Final Solution':

The public has already endorsed some important initiatives against smokers, driving them out of homes, workplaces, public transport and other public places. It is now time for the government to take the campaign a step further...Recalcitrant smokers could be driven in trucks from the inner city estates where they are concentrated to these camps in remote rural areas. In Cambodia in the 1970s, Pol Pot, a pioneer of the new public health, used this approach to achieve a dramatic reduction in mortality from smoking. It is fortunate that the new government has shown that it is capable of the sort of tough thinking necessary to devise a final solution to the tobacco problem. No doubt there will remain a hard core of those so corrupted by tobacco, its profits and its toxins, that they will refuse to give it up. Filthy habit, filthy people - they will have to be exterminated. The camps can then make room for all the other deviants whose behaviour is designated a major problem of public health - those who are overweight and not inclined towards exercise, those who drink more than the prescribed number of units of alcohol and take illicit drugs[31]

Paedophilia

Fitzpatrick argues that a new obsession with the issue of child sexual abuse has occurred without a concurrent rise in actual abuse, that feminist calls for the use of the criminal justice system will increase the oppression of women, and that the real reason for the obsession is an 'industry' which seeks to gain from increased incidences of abuse and the state's thirst for increased control over people's personal lives.

Creating panic/Managing risk

Fitzpatrick describes concern around the issue of child abuse as an effort by the state to extend its control over people's personal lives. As such he seeks to portray the issue as society panicking, which implies an exagerated perception of risk:

To explain the intensity and the pervasiveness of the public preoccupation with child sexual abuse, we must look to the wider sense of moral crisis that has engulfed Western society in recent years...The panic about child sexual abuse is another symptom of our anxious age. Here is the most extreme and degrading manifestation of the disintegration of the traditional family, which is also evident in the statistics of divorce and single parenthood, and in impressions of rampant juvenile crime[32]

Feminism as Patriarchy

Fitzpatrick also argues that using traditionally patriarchal state institutions, such as the police, against perpetrators of sexual violence, usually men, will inevitably lead to greater oppression of women. However, this clearly ignores the point that refusing to use these institutions in the absence of any alternative inevitably leaves the victims of abuse with no recourse for justice nor defence, and would ensure such institutions remain patriarchal and perpetrators of abuse retain control over victims:

Two British feminists argued for 'the exclusion of abusive men' through criminal proceedings (M MacLeod and E Saraga, 'Child sexual abuse: challenging the orthodoxy', Feminist Review, No28 1988). The feminists' main challenge to orthodoxy is their demand for the use of the state's repressive apparatus within the family. MacLeod and Saraga explicitly repudiate the traditional reticence of the left about state coercion. 'Recently', they note, 'a more complex analysis of state intervention has brought the work and ideas of feminists and some statutory agencies closer together'...It is ironic that the feminists are now inviting the 'patriarchal' state to tackle the problems of the violent patriarch. In reality, the state that safeguards the running of British capitalism at home and abroad has a capacity for violence that vastly exceeds that of the most psychopathic and chauvinist husband. The notion that this state could 'empower not oppress women and children' is an absurdity...The feminist argument combines utopian fantasy with an invitation to repression[33]

State power

In a similar analysis to his view of the 'Aids establishment', he appears to suggest that the risk of child abuse is elevated by 'interested parties' who will gain work, or an increase in power, as a result of an increase in perceived cases of child abuse:

For social workers, doctors, psychiatrists and psychologists, child sexual abuse is a growth area in a contracting market. It provides career opportunities, research prospects, and lots of case conferences to make everybody feel important. Back in 1988, MacLeod and Saraga complained that 'feminist theory is still "out in the cold" when it comes to the professional establishment'. Not any more. When it comes to calls for criminal proceedings, everybody can chorus 'we're all feminists now'...The result of more than five years of public concern about child abuse is the increase in state power and authority over family life. This does nothing to help abused children, but it reinforces the grip of a decadent establishment over a demoralised society[34]

BSE/CJD

The topic of BSE is frequently cited by members of the LM Network to justify their claims that society is currently in a heightened sense of panic, highly risk averse and obsessed with the precautionary principle. Fitzpatrick wrote a number of articles along these lines, also adding the idea that 'greens' and 'environmentalists' may have had something to do with the 'panic' surronding BSE. This argument is perhaps used in an effort to belittle concerns of environmentalists and equate all issues raised with new technology with undue panic.

Creating panic/Managing Risk Fitzpatrick argues the likelihood of a link between BSE and CJD was given excessive credence by the state and quango's:

The great mad cow panic did not begin in rural England or even in the media: it was launched by parliamentary statements by the ministers of health and agriculture on 20 March, which for the first time endorsed the possibility of a link between BSE, beef and CJD.[35]

Fitzpatrick also argues the BSE crisis was based on a society constantly in search of a health scare:

Recent events mark a historic achievement for the cult of the new public health - a health scare, not about a disease, but about the possibility of a disease. In the increasingly virtual reality of late twentieth-century society, we have a real panic about a virtual disease.[36]

BSE and the Precautionary Principle

He argues that the case of BSE demonstrates a risk averse society and appears to suggest that fears surrounding nuclear energy and global warming should be considered as a result of this anxiousness, rather than given any credence:

Why then, if there is no evidence that BSE causes CJD, is there such a wave of panic about the dangers of eating beef? ...The first is the psychology of the contemporary 'risk society'. The panic about mad cow disease took off in a society which has become preoccupied with collective fears of impending doom and with individual anxieties about threats to health, security and safety. We worry about nuclear war and global warming, AIDS and Ebola, mugging and burglary, road rage, child abuse and violence against women.[37]

In another article he links concern for public health, global warming, nuclear energy, domestic violence and child abuse as having caused this anxious society, and creating a society obsessed with diet:

In our increasingly insecure society, in which familiar social and political landmarks have disappeared, there is a striking tendency to exaggerate the risks of everyday life and to live with a heightened sense of danger, if not one of impending doom. Pressure groups emphasise particular dangers - of nuclear radiation, global warming, atmospheric pollution or of male violence, crime, or diverse forms of abuse. Health hazards resulting from the environment or from individual lifestyle factors are a constant theme of public discussion. Diet provides the link between concerns about environmental threats to health and individual choice[38]

For Fitzpatrick all of these concerns demonstrate a society obsessed with risk:

The notion that we live today in a 'risk society' is increasingly influential. One of the guidelines that has emerged to regulate the 'risk society' is the 'precautionary principle'. This means that unless something can be proved to be safe, don't do it. The logic of this applied to the BSE/CJD controversy is clear: until it can be proved that BSE does not cause CJD, then avoid beef and beef products. As it will take decades to demonstrate this, the precautionary principle dictates lifelong vegetarianism - and close attention to food packages to detect hidden beef products. This may not seem any great sacrifice, but applied systematically to everyday life, the precautionary principle means a life of caution, restraint and, ultimately, resignation[39]

Society Anti-science

He argues society is moving towards the rejection of science, which may have elevated the panic surrounding BSE:

Another factor contributing to the mad cow disease panic is the popular hostility towards modern farming techniques which are widely regarded as a violation of the laws of nature. From this perspective, BSE is, like the lethal viruses that are said to threaten new plagues, an example of the revenge of nature against human arrogance and interference[40]

He also suggests that environmentalism and vegetarianism are indicators of an anti-science mentality:

In recent years there has been a steady growth in the influence of a set of broadly green, pro-animal, anti-science and technology ideas. These are expressed in the rise of vegetarianism, in an increasingly widespread distaste for intensive farming techniques and in popular campaigns against the transport of live animals and against McDonalds. For people who hold such sentiments, the thesis that BSE causes CJD has an instant attraction: it confirms their view that the production and consumption of meat are evil, and provides them with the additional argument that meat is also dangerous[41]

Green/Environmentalist elite capture

He suggests the national curriculum has been 'corrupted' by green prejudice, which has perhaps increased society's fatalism:

These views reflect modern society's extraordinary collapse of confidence in itself. It is a simple fact, familiar to every schoolchild before the corruption of the national curriculum by green prejudice, that human civilisation is based on 'breaking the rules' of nature, on increasing the productivity of nature by cultivating plants and domesticating animals[42]

He also laments the rise in vegentarianism as contradictory to human development and suggests it is no surprise that a one of the leading proponents of BSE/CJD link is a known vegitarian:

While in the past support for vegetarianism and animal rights were the province of religious zealots, eccentrics, and film and pop stars, these causes today command growing popular - and establishment - support. Academic philosophers and scientists can readily be found to contradict the rational and humanist foundations of modern civilisation... One of the leading proponents of the BSE/CJD link is Professor Richard Lacey, a medical microbiologist whose works are published by the Vegetarian Society. For him, the link is a matter of faith which does not require substantiation by epidemiological or other scientific evidence[43]

Writing for Spiked (2001-Present)

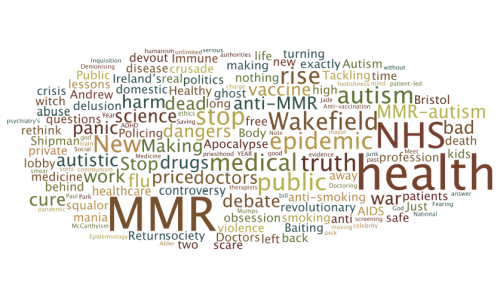

Fitzpatrick has written articles for Spiked regularly since 2000, contributing 183 articles. The main topics he focused on in Spiked were issues surrounding MMR, particularly in relation to the Andrew Wakefield 'scandal' and suggested links with autism, public health issues and changes to the NHS.

Writing for Tobacco (2002)

In 2002 Michael Fitzpatrick wrote an article for the tobacco funded Risk of Freedom Briefing publication in which he argued society had been medicalised to such an extent that people's personal lives had been invaded, undermining their autonomy and promoting dependency. He appears to question a number of modern definitions of illnesses, particularly those of a psychological nature, arguing many of these definitions allow people to avoid taking personal responsibility for their emotions:

The shift of medical practice away from the treatment of disease towards the regulation of personal behaviour draws doctors into areas in which they have neither competence nor expertise....The medicalization of society reinforces popular anxieties about health and fears about disease. Professional intrusion in personal life undermines individual autonomy and encourages dependency. The proliferation of disease labels, from post-traumatic stress disorder and social phobia to myalgic encephalomyelitis ('ME') and fibromyalgia, tends to prolong incapacity and inflates rates of disability. A return

to the old labels — ‘sadness’, ‘fear’, ‘laziness’, ‘apathy’ — would also point the way to the old, and often effective cures[44]

Affiliations

The Progress Club (Company number 04331329, created 29 November 2001) Directors along with: Geoff Kidder and Para Mullan[45]

Career Chronology

- 1988 (approx)[46] - 2013[47]NHS -GP in Stoke Newington, London

- Early 2000-September 2000 - Forum of the Social Issues Research Centre[48]

- 2001-Present - Spiked – Contributor/Writer and health correspondent

- 2002-2012 - British Journal of Medical Practice – Contributor/Writer

- 2003-2007 - The Lancet - Contributor/Writer

- 2006-Present - Battle of Ideas – Panel expert

- May 2007-March 2011 - Community Care – Contributor/Writer

- 2009 - Progress Educational Trust - Contributor/Writer

- May 2010-Present - Sense About Science – Trustee

- Ocotber 2013-Present[49] -Autistica - Contributor/Writer

Educational Background

- University of Oxford - Medicine[50]

- Middlesex Hospital - Medical training[51]

Other Links with the Network

Battle of Ideas Panel appearances

2005

- Sunday 30th October 2005 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Professor Brian Barry (author of Culture and Equality), Professor Simon Blackburn (Professor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge, Contributor to 'The Changing Role of the Public Intellectual' edited by Dolan Cummings), Professor Todd Gitlin (Professor of journalism and sociology at Colombia University Graduate School, Jewish People Policy Institute, Democratiya), and Dolan Cummings (associate fellow, Institute of Ideas; editor, Debating Humanism; was a co-founder of the Manifesto Club, editorial director of the Institute of Ideas, is the editor of Culture Wars, writes for Spiked), discussing 'Reassessing the Enlightenment?' at the Battle of Ideas[52].

2006

- Saturday 28th October 2006 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Professor Malcolm Johnson (director, International Institute on Ageing and Health), Raymond Tallis (professor of geriatric medicine, University of Manchester, has collaborated with Frank Furedi), Dr Tony Walter (reader in sociology, University of Reading and Centre for Death and Society, University of Bath), and Tiffany Jenkins (arts and society director, Institute of Ideas, wrote for Living Marxism, and Spiked), discussing ‘Morbid Fascinations – our obsession with death’ at the Battle of Ideas[53].

- Saturday 28th October 2006 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Michael Baum (professor emeritus of surgery and visiting professor of medical humanities, University College London, Hadassah UK), Jim Pollard (writer and editor, [Malehealth.co.uk 'Malehealth']), Dr Dana Rosenfeld (lecturer, Department of Health and Social Care, Royal Holloway, University of London; co-editor, Medicalized Masculinities), and Dr Liz Frayn (senior house officer in psychiatry, Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust, has written for Living Marxism and Spiked), Dr Tony Walter (reader in sociology, University of Reading and Centre for Death and Society, University of Bath), ‘Playing Balls – why are men becoming obsessed with their health?’, at the Battle of Ideas[54].

2007

- Sunday 28th October 2007 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Dominic Lawson (columnist, Independent and Mail on Sunday; visiting fellow, Reuters Institute, University of Oxford; editor, Snake Oil and Other Preoccupations), Dr David Runciman (professor of politics, Department of Politics and International Studies (POLIS), Cambridge University), Matthew Taylor (chief executive, RSA; former chief advisor on strategy to prime minister, Tony Blair, IPPR), discussing ‘Post Ideology’ at the Battle of Ideas[55].

- Sunday 28th October 2007 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Dr Tristram Hunt (broadcaster; lecturer in modern British history, Queen Mary, University of London, involved in the setting up of the Science Media Centre), and Bruno Waterfield (Brussels correspondent, Daily Telegraph; has written for Living Marxism, and has links to Manifesto Club), discussing ‘Frederick Engels’, at the Battle of Ideas[56].

2008

- Sunday 2 November 2008 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Dr Clare Gerada (GP; past chair, Royal College of General Practitioners), Dr Peter Marsh (co-director, The Social Issues Research Centre), Dr Gray Smith-Lang (consultant gastroenterologist, Medway Maritime Hospital), and Tony Gilland (associate fellow, Institute of Ideas, has written for Spiked), discussing ‘Boozy Britain’ at the Battle of Ideas[57].

2009

- Monday 12th October 2009 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Professor Richard E. Ashcroft (professor, bioethics, Queen Mary, University of London; deputy editor, Journal of Medical Ethics), Dr Elisabeth Hill (senior lecturer, Goldsmiths College, University of London; co-editor, Autism: mind and brain), Professor Stuart Murray (professor, contemporary literatures and film, University of Leeds), Sandy Starr (communications officer, Progress Educational Trust; webmaster, BioNews, has written for Living Marxism and Culture Wars, written for Spiked, is a member of the Manifesto Club, and adjudged for Debating Matters), and Dr Shirley Dent (founder, Spark Mobile; communications specialist (currently working with the British Veterinary Association media team, writes for Spiked and is a member of the Manifesto Club), discussing ‘Age of Autism: rethinking 'normal, at the Battle of Ideas[58].

- Sunday 1st November 2009 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Professor Raanan Gillon (emeritus professor, medical ethics, Imperial College London), Professor David Oliver (national clinical director for older people, Department of Health; consultant physician, Royal Berkshire Hospital), Adam Wishart (award-winning writer and documentary maker, The Price of Life and Monkeys, Rats and Me), and Helen Britwistle (History Teacher, former resources and communications manager, Debating Matters Competition), discussing ‘Is the NHS institutionally ageist?’, at the Battle of Ideas[59].

2010

- Saturday 30th October 2010 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Dr Clare Gerada (GP; past chair of Royal College of General Practitioners), Katherine Murphy (Chief executive, the patients association), Roger Taylor (co-founder and research director, Dr Foster Intelligence), and Bríd Hehir (development manager Do Good Charity; former NHS health visitor and senior manager, has written for Living Marxism and Spiked), discussing ‘Patient centred healthcare: the right to choose?’, at the Battle of IdeasSee ‘Patient centred healthcare: the right to choose?’, 30 October 2010, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015</ref>.

- Saturday 30th October 2010 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Professor Virginia Berridge (director, Centre for History in Public Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine), Professor Mike Kelly (director, Centre of Public Health Excellence, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)), Kristin Wolfe (head of alcohol policy, SABMiller), and Suzy Dean (freelance writer; blogger for free society, linked to Manifesto Club, writes for Spiked, works for ClerksWell/CScape), discussing ‘The war on alcohol: new puritanism or healthy sobriety’, at the Battle of Ideas[60].

2011

- Saturday 29th October 2011 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Roger Howard (former chief executive, UK Drug Policy Commission; chair, Build on Belief), Professor Neil McKeaganey (director, Centre for Drug Misuse Research), Dr Fiona Measham (senior lecturer, criminology, Lancaster University; chair, Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs Polysubstance Use Working Group), Suzy Dean (freelance writer; blogger for free society, linked to Manifesto Club, writes for Spiked, works for ClerksWell/CScape), discussing ‘Your mind, your high: is recreational drug use morally wrong?’, at the Battle of Ideas[61].

- Sunday 30th October 2011 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Johannes Busse (chair, London group of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD)), Rowenna Davies (Labour councillor, Southwark), Paul Kelly (professor of political theory and head, department of government, LSE), and Peter Smith (director of tourism, St. Mary’s University College, Twickenham, London, writes for Spiked), discussing ‘Can social democracy survive the 21st Century?’, at the Battle of Ideas[62].

2012

- Sunday 21st October 2012 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Andrew Copson (chief executive of the British Humanist Association), Alom Shaha (writer and science teacher), Mark Vernon (journalist) and Dolan Cummings (associate fellow, Institute of Ideas; editor, Debating Humanism; was a co-founder of the Manifesto Club, editorial director of the Institute of Ideas, is the editor of Culture Wars, and writes for Spiked), discussing ‘Atheism: What's the point?’, at the Battle of Ideas[63].

- Thursday 15th November 2012 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Dr Owen Bowden-Jones (consultant psychiatrist and chair, Faculty of Addictions, Royal College of Psychiatrists), Tim Hollis (chief constable, Humberside Police; chair, ACPO Drugs Committee), Molly Meacher (chair, All Party Parliamentary Group on Drug Policy Reform), Maryon Stewart (author and broadcaster; pioneer in non-drug medicine; Founder, Angelus Foundation; nutritionist, C4's Model Behaviour; presenter, The Really Useful Health Show), David Bowden (coordinator, UK Battle Satellites; columnist for Spiked), discussing ‘The law's drug problem: the challenge of legal highs’, at the Battle of Ideas[64].

2013

- Saturday 19th October 2013 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Anne Atkins (novelist, columnist and broadcaster), Ruth Dudley Edwards (columnist, Irish Sunday Independent; blogger, Daily Telegraph, member of the Advisory Board of the New Culture Forum), Joe Friggieri (professor of philosophy and former head of department, University of Malta), Dolan Cummings (associate fellow, Institute of Ideas; editor, Debating Humanism; was a co-founder of the Manifesto Club, editorial director of the Institute of Ideas, is the editor of Culture Wars, and writes for Spiked), discussing 'Do as I say not as I do: what's wrong with hypocrisy?' at the Battle of Ideas[65].

- Saturday 19th October 2013 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Dr Frankie Anderson (doctor in neurorehabilitation; co-founder, Sheffield Salon), Dr Henrietta Bowden-Jones (director, National Problem Gambling clinic), Dr Sally Satel (resident scholar, American Enterprise Institute), Phil Withington (professor of early modern history, University of Sheffield), and David Bowden (coordinator, UK Battle Satellites; columnist for Spiked), discussing 'What is addiction?' at the Battle of Ideas[66].

- Sunday 20th October 2013 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Tom Chivers (assistant comment editor, Daily Telegraph), Hannah Devlin (Science editor, The Times), Mark Henderson (head of communications, Wellcome Trust), Dr Jamie Whyte (philosopher and writer), Craig Fairnington (online resources manager, Institute of Ideas), discussing ‘Science journalism: the tyranny of evidence?’, at the Battle of Ideas[67].

2014

- Sunday 19th October 2014 - Michael Fitzpatrick featured on a panel with: Henry Ashworth (chief executive, The Portman Group; former member, Cabinet Office's Behavioural Insights Team), Michael Blastland (writer and broadcaster; presenter, The Human Zoo, Radio 4; co-author, The Tiger That Isn't), Dr Elizabeth Pisani (director, Ternyata Ltd; author, The Wisdom of Whores: Bureaucrats, Brothels and the Business of AIDS), and Timandra Harkness (journalist, writer & broadcaster; presenter, The Singularity & other BBC Radio 4 programmes; writer & performer, science-based comedy shows including BrainSex, has written for Living Marxism, writes for Spiked, produces and hosts Battle of Ideas events, has chaired part of an Audacity event and was director of Engaging Cogs, also has links with Culture Wars, the Institute of Ideas, and the Manifesto Club), discussing 'The science of public health: where’s the evidence?', at the Battle of Ideas[68].

Publications

1980-1989

1982

- Michael Fitzpatrick (as Mike Freeman), Malvinas are Argentina’s Revolutionary Communist Party, Junius Publications, 1982.

1987

- Michael Fitzpatrick and Don Milligan, 'The truth about the AIDS panic', Junius, 1987.

1990-1995

1990

- Linda Ryan, Dr Michael Fitzpatrick and Don Milligan, 'Aids', Living Marxism, No. 15 - January 1990, p. 14.

1992

- Michael Fitzpatrick, The politics of health, Living Marxism, No. 43 - May 1992, p. 16.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Aids panic in disarray', Living Marxism, No. 45 - July 1992, p. 17.

- Michael Fitzpatrick and Ian Scott, 'The truth about the Birmingham Aids panic', Living Marxism, No. 46 - August 1992, p. 20.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The dangers of healthy living', Living Marxism, No. 47 - September 1992, p. 26.

1993

- Michael Fitzpatrick (as Mike Freeman), The Empire Strikes Back: Why We Need A New Anti-Imperialist Movement, Revolutionary Communist Party, Junius Publications, 1993.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Aids: the truth about the Day report', Living Marxism, No. 58 - August 1993, p. 24.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Child sex abuse panics', Living Marxism, No. 60 - October 1993, p. 16.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Peace in Ireland?', Living Marxism, No. 61 - November 1993, p. 14-15.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Handicapped or oppressed?', Living Marxism, No. 62 - December 1993, p. 24.

1994

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The 'underclass' debate', Living Marxism, No. 73 - November 1994, p. 26.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The asthma myth', Living Marxism, No. 74 - December 1994, p. 23.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The Pope', Living Marxism, No. 74 - December 1994.

1995

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Futures: Fear of frying', Living Marxism, No. 75 - January 1995, p. 20.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Taboos: 'Repressed memory': a morbid symptom', Living Marxism, No. 78 - April 1995, p. 8.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Outbreak', Living Marxism, No. 80 - June 1995.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Medical TV dramas', Living Marxism, No. 82 - September 1995.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Futures: An epidemic of fear', Living Marxism, No. 84 - November 1995, p. 18.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'People's history', Living Marxism, No. 84 - November 1995.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The Marxist Review of Books', Living Marxism, No. 85 - December 1995, p. 43.

1996 -2000

1996

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Rationing health: a doctor speaks', Living Marxism, No. 86 - January 1996, p. 16.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'BSE scare: a mad, mad, mad, mad world', Living Marxism, No. 87 - February 1996, p. 14.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The great mad cow scare', Living Marxism, No. 90 - May 1996, p. 24.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The problem of parenting', Living Marxism, No. 91 - June 1996, p. 8.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Futures: The diseases of modern civilisation', Living Marxism, No. 93 - September 1996, p. 34.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Warning: Anti-tobacco crusades can damage your life', Living Marxism, No. 94 - October 1996, p. 16.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second opinion', Living Marxism, No. 95 - November 1996, p. 23.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second opinion', Living Marxism, No. 96 - December/January 1996/1997, p. 27.

1997

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'No balls', LM 97, February 1997.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Doctoring the family', LM 98, March 1998.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Is Blair Tina's heir?', LM 100, p. 20, May 1997.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Selling Aids awareness', LM 99, p. 37, April 1997

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: Doctoring an unhealthy society', LM 100, p. 37, May 1997.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Fundholding, New Labour-style', LM 101, p. 27, June 1997.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Ireland imports health panics', LM 102, p. 37, July/August 1997.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: A pig's heart: go for it!', LM 103, September 1997, p. 37.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Beware the rampant id', LM 104, October 1997.

1998

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'No backbone in beef crisis', LM 107, p. 32, February 1998.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: New Labour New NHS?', LM 107, p. 42, February 1998.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Exterminate the filthy smokers', LM 108, p. 37, March 1998.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The tyranny of health', LM 109, p. 24, April 1998.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Big girls and health zealots', LM 109, p. 33, April 1998.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: The ethics of cannabis', LM 110, p. 21, May 1998.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: The drugs campaign - just say no', LM 111, p. 23, June 1998.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Reading between the lines', LM 111, p. 43, June 1998.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second opinion: The significance of Bristol', LM 112, p. 33, July/August 1998.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: MMR madness', LM 113, p. 31, September 1998.

- Jennie Bristow, Mark Pendergrast and Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Whatever happened to false memory syndrome?', LM 113, p. 32, September 1998.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second opinion: Radical remedies', LM 114, October 1998, p. 32.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: Viagra and the staff of life', LM 115, November 1998, p. 41.

- Paul Colbert and Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Should men worry more about their health?', LM 116, p. 30, December/January 1998/1999.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: Awareness makes you sick', LM 116, p. 37, December/January 1998/1999.

1999

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: NHS crisis - what crisis?', LM 117, p. 41, February 1999.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Gulf War syndrome does not exist', LM 118, p. 10, March 1999.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second opinion: Domestic violence - NOT a healthcare issue', LM 118, p. 43, March 1999.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: Naming and shaming', LM 119, p. 39, April 1999.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: Patients getting physical?', LM 120, p. 41, May 1999.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: The problem of racist patients', LM 121, p. 41, June 1999.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: The methadone police', LM 122, p. 29, July/August 1999.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: Healthy living centres: millennial healing', LM 123, p. 39, September 1999.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Why 'social exclusion' is the in thing', LM 124, p. 34, October 1999.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second opinion: Who needs guidelines?', LM 124, p. 39, October 1999.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: Sex in the surgery', LM 125, p. 41, November 1999.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Impoverished politics', LM 126, p. 18, December/January 1999/2000.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: A great leap forward', LM 126, p. 39, December/January 1999/2000.

2000

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Tony Blair's therapeutic state', LM 127, p. 8, February 2000.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: Dr Patel and Dr Smith', LM 127, p. 37, February 2000.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'NHS in traction', LM 128, p. 8, March 2000.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: The dangers of deference', LM 128, p. 35, March 2000.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Addiction addicts', LM 129, p. 24, April 2000.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: Screen test', LM 129, p. 37, April 2000.

2001-2005

2001

- Michael Fitzpatrick, The tyranny of health: doctors and the regulation of lifestyle, London: Routledge, 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Amnesty' for dead organs: morbid anatomy', Spiked, 8 March 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'ADHD: turning a problem into a disease', Spiked, 8 March 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Addiction addicts', Spiked, 13 March 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Epidemiology uncovered', Spiked, 13 March 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The Queniborough CJD cluster ', Spiked, 27 March 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Why 'awareness' is bad for your health', Spiked, 30 March 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The price of precaution', Spiked, 4 April 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Dioxin: a toxin for our times', Spiked, 25 April 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Doctors on the defensive', Spiked, 1 May 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The hidden cost of free condoms', Spiked, 8 May 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'spiked-geist: Day 16', Spiked, 23 May 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Keep politics out of healthcare', Spiked, 31 May 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Public squalor or private rip-off?', Spiked, 5 June 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'spiked-proposals: The NHS', Spiked, 7 June 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Policing patients', Spiked, 19 June 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, The dangers of 'safe sun', Spiked, 26 June 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Body parts: part two', Spiked, 4 July 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Bristol Inquiry: key questions', Spiked, 19 July 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'New Labour's health cares', Spiked, 26 July 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The high price of Alder Hey', Spiked, 7 August 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'After Bristol: the humbling of the medical profession', Spiked, 16 August 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'An intelligent guide to medicine', Spiked, 10 September 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Blair's gospel of despair', Spiked, 5 October 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The lessons of the drugs war', Spiked, 9 October 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Anthraxiety', Spiked, 17 October 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The fear within', Spiked, 2 November 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Policing the medical profession', Spiked, 29 November 2001.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'NHS in traction', Spiked, 13 December 2001.

2002

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Doctoring domestic violence', Spiked, 7 February 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Debating the disease', Spiked, 14 February 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Immune to the evidence', Spiked, 14 February 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Myths of immunity', Spiked, 18 February 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Screening wars', Spiked, 26 February 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'An overdose of medical ethics', Spiked, 15 March 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Making a spectacle of ourselves', Spiked, 26 March 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Medicalising everyday life', Spiked, 17 April 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Catholicism in crisis', Spiked, 1 May 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Return of the babysnatchers?', Spiked, 8 May 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Andrew Wakefield: misguided maverick', Spiked, 20 May 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Body politics', Spiked, 5 June 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'MMR: the making of junk science', Spiked, 5 July 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Drugs debate: high on myths', Spiked, 11 July 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'AIDS in Britain: why complacency is justified', Spiked, 17 July 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Put alternative medicine back in its box', Spiked, 26 July 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Leaving the left behind', Spiked, 30 July 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, The 'Death of the Subject', Spiked, 2 August 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Training doctors as therapists', Spiked, 19 September 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Targeting doctors', Spiked, 30 September 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'A Poxy Panic', Spiked, 11 October 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Infected by panic', Spiked, 1 November 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The therapeutic society', Spiked, 19 November 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Mumps vaccine: swollen concerns', Spiked, 21 November 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Rabid warnings', Spiked, 26 November 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The rehab don't work', Spiked, 19 December 2002.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Making everything hard work', Spiked, 23 December 2002.

2003

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Breaking psychiatry's chains', Spiked, 3 January 2003.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Apocalypse from now on', Spiked, 25 April 2003.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Immune to the facts', Spiked, 27 May 2003.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Signing away the NHS', Spiked, 4 June 2003.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Hear the Silence', Spiked, 4 December 2003.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'MMR: Fact and fiction', Spiked, 11 December 2003.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Medicine on trial', Spiked, 15 December 2003.

2004

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'MMR: risk, choice, chance', British Medical Bulletin, 2004, Volume 69(1), pp. 143-153.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'A New Year prescription', Spiked, 5 January 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'After Shipman', Spiked, 16 January 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The cot death controversy', Spiked, 10 February 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'MMR: Investigating the interests', Spiked, 23 February 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'MMR: the controversy continues', Spiked, 15 March 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Demonising Drink', Spiked, 10 May 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Straw nanny', Spiked, 19 July 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Anti-vaccination nation?', Spiked, 9 September 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, MMR: ‘A reparation, of sorts’, Spiked, 22 September 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The sickness at the heart of modern healthcare', Spiked, 27 September 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'We have ways of making you stop smoking', Spiked, 15 November 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'How did the doctor get away with it?', Spiked, 19 November 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Why the drugs don’t work', Spiked, 8 December 2004.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The ghost of Harold Shipman', Spiked, 10 December 2004.

2005

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Fearing flu', Spiked, 27 January 2005.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'David Widgery: did he lose faith?', Spiked, 1 February 2005.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, ‘Agents of persuasion’? Just say no, Spiked, 10 March 2005.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'After John Paul II', Spiked, 8 April 2005.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Mercury and autism: a damaging delusion', Spiked, 13 May 2005.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Society’s unhealthy obsession with abuse', Spiked, 27 June 2005.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The price of multiculturalism', Spiked, 5 August 2005.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Patient power can harm your health', Spiked, 7 October 2005.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'When quackery kills', Spiked, 4 November 2005.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The death agony of the anti-MMR campaign', Spiked, 11 November 2005.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The absurdity of a ‘patient-led’ NHS', Spiked, 21 November 2005.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Pandemic flu: turning a drama into a crisis', Spiked, 25 November 2005.

2006-2010

2006

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Why do we carry on screening?', Spiked, 16 January 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The dangers of the crusade against cancer', Spiked, 27 January 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'A sickening White Paper', Spiked, 6 February 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The stigma of smoking', Spiked, 21 February 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'After Northwick Park: we need more research, not less', Spiked, 21 March 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'McDonald’s: why the parents of autistic kids are lovin’ it', Spiked, 2 May 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'MMR is safe - so why are many still scared of it?', Spiked, 9 May 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Stop bullying fat kids', Spiked, 24 May 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Doctors cannot stop domestic violence', Spiked, 15 June 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Stop witch-hunting Wakefield', Spiked, 19 June 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Big Pharma: a paper tiger?', Spiked, 3 July 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The trouble with autism-lit', Spiked, 21 July 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, Capital: ‘There’s nothing remotely like it’, Spiked, 22 August 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Autism: lack of services is the cruel joke', Spiked, 8 October 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The new priesthood of the kitchen', Spiked, 18 October 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Children: they aren’t what you feed them', Spiked, 26 October 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Get off the couch!', Spiked, 14 November 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'A green bill of health?', Spiked, 21 November 2006.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The Dawkins delusion', Spiked, 17 December 2006.

2007

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The anti-MMR gravy train derailed', Spiked, 12 January 2007.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'You’re so vain, Nick, you think this war is about you', Spiked, 2 February 2007.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Just Say No to this ‘radical rethink’ on drugs', Spiked, 12 March 2007.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'What’s behind the ‘autism epidemic’?', Spiked, 20 April 2007.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Empowering patients: New Labour’s unhealthiest idea?', Spiked, 11 May 2007.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Dumbing down doctors', Spiked, 18 May 2007.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Baiting the devout', Spiked, 21 June 2007.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, ‘The MMR-autism theory? There’s nothing in it’, Spiked, 4 July 2007.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Baiting the devout', Spiked, 13 July 2007.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The dark art of the MMR-autism panic', Spiked, 17 July 2007.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Why did communism survive for so long?', Spiked, 31 August 2007.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Measles: the bitter results of a rash panic', Spiked, 3 September 2007.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The Doublespeak of the Darzi review', Spiked, 8 October 2007.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Was Jesus a revolutionary?', Spiked, 21 December 2007.

2008

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Healthy in mind and body… what about spirit?', Spiked, 9 January 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Anti-MMR mania: diagnosis and cure', Spiked, 25 January 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The rise and fall of anti-MMR mania', Spiked, 1 February 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'I’m backing Boris for London mayor', Spiked, 31 March 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'How the British left betrayed Ireland’s 1968', Spiked, 25 April 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, ‘Healthy living’ zaps the fun from life, Spiked, 30 April 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, Derry 1968: Ireland’s ‘moment of truth’, Spiked, 9 May 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Taking a political placebo', Spiked, 13 June 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The real choice: public or private squalor', Spiked, 1 July 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The authorities have lied, and I am not glad', Spiked, 29 August 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, AIDS epidemic? It was a ‘glorious myth’, Spiked, 5 September 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, Tackling the epidemic of ‘bad science’, Spiked, 22 September 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Childhood obesity is not a form of child abuse', Spiked, 8 October 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, Tackling the epidemic of ‘bad science’, Spiked, 24 October 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, ‘Crusade against autism’: doing more harm than good, Spiked, 29 October 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'A Salvation Army without the brass band', Spiked, 11 November 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, The ghost of the ‘refrigerator mother’, Spiked, 24 November 2008.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, False prophets in the ‘crusade against autism’, Spiked, 4 December 2008.

2009

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The MMR scare: from foolishness to fraud?', Spiked, 10 February 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'MMR-autism scare: the truth is out at last', Spiked, 23 February 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Jade and the dangers of smear testing', Spiked, 23 March 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'It’s time to stop this ‘miracle cure’ madness', Spiked, 6 April 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'An open letter to Gordon Brown', Spiked, 14 April 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Asking questions is not an ‘Inquisition’, Spiked, 11 May 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Don't mention the d-word', New Scientist, 12 May 2010, Volume 206(2760), p. 44.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Neither Leveller nor statist', Spiked, 29 May 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'An unlimited appetite for past obscenities', Spiked, 3 June 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'In praise of Engels', Spiked, 19 June 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'When public health becomes a public nuisance', Spiked, 6 July 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Childish jibes are no substitute for serious debate', Spiked, 25 September 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, Stop this witch hunt against ‘evil deniers’, Spiked, 9 October 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Making a pig’s ear of the vaccination debate', Spiked, 27 October 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The anti-smoking ‘truth regime’ that cannot be questioned', Spiked, 30 October 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Autism: moving beyond the quest for a cure', Spiked, 5 November 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The ‘McCarthyism’ of the anti-smoking lobby', Spiked, 13 November 2009.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The drift towards professional parenting must be resisted', Community Care, 25 November 200

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'A pandemic of fantasy flu', Spiked, 22 December 2009.

2010

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The war on Dr Wakefield: only 12 years too late', Spiked, 2 February 2010.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Turning a blind Eye to the truth', Spiked, 1 March 2010.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Public health and the obsession with behaviour', Spiked, 5 May 2010.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Censorship is not the answer to health scares', Spiked, 25 May 2010.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Apocalypse looms – again', Spiked, 16 August 2010.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'A futile intervention into our drinking habits', Spiked, 15 November 2010.

2011-2015

2011

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The real lessons of the MMR debacle', Spiked, 25 January 2011.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The rise and rise of anti‑vaccine agitators', Spiked, 25 February 2011.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Meet the new breed of anti‑vaccine agitator', Spiked, 4 March 2011.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, ‘There's never been a better time to be autistic’, Spiked, 25 March 2011.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Save our National Health Service? Why, exactly?', Spiked, 7 April 2011.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Don’t tinker with the NHS. Completely rethink it', Spiked, 20 June 2011.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Note to NHS: stop treating the public with contempt', Spiked, 18 October 2011.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Our society is hooked on harm reduction', Spiked, 10 November 2011.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Social democracy is dead. Now let’s move on', Spiked, 14 November 2011.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'From revolutionary student to Byronic celebrity', Spiked, 20 December 2011.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Saving medical practice from the tyranny of health', Spiked, 23 December 2011.

2012

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'After 'New Atheism', let's re-humanise humanism', Spiked, 16 & 30 November 2012.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The charge of the anti-enlightenment brigade', Spiked, 12 December 2012.

2013

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The rise of pseudo-scientific links lobby', Spiked, 24 January 2013.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Andrew Wakefield: Return of the wicked witch', Spiked, 16 April 2013.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'MMR/autism: one step forward, two steps back', Spiked, 12 June 2013.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'No, autistic children are not the spiritual saviours of mankind', Spiked, 23 August 2013.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Even quacks must have free speech', Spiked, 19 November 2013.

2014

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'God is dead, long live god', Spiked, 13 June 2014.

- Michael Fitzpatrick, 'AND THE BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD GOES TO…spiked writers pick their best reads of 2014', Spiked, 19 December 2014.

Notes

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'author affiliations', British Medical Bulletin, 2004, Volume 69 (1), pp. 143-153.

- ↑ Speaker profile Battle of Ideas, acc 23 Mar 2011

- ↑ See Tracey Brown, 'Where Sense About Science comes from', 1 June 2012, Sense About Science, accessed 5 March 2015.

- ↑ "Articles by Michael Fitzpatrick", Spiked website, accessed 2 May 2010

- ↑ Michael Fitzpatrick, Progress Educational Trust

- ↑ Board of trustees, SAS website, acc 10 May 2010

- ↑ George Monbiot, “Invasion of the entryists”, The Guardian, 9 December 2003

- ↑ “Interview with George Monbiot”, LobbyWatch, April 2007; “Profiles - Living Marxism", LobbyWatch, accessed April 2009

- ↑ Sense About Science website contact page, version placed in web archive 29 Oct 2003, acc in web archive 2 May 2010, screengrab here

- ↑ Global Futures contact page, version of 2002, accessed in web archive 2/5/2010, screengrab here

- ↑ Based on Internet archive captures of the funders list published on the Sense about Science website, accessed 5 March 2015.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'MMR: risk, choice, chance', British Medical Bulletin, 2004, Volume 69(1), pp. 143-153.

- ↑ We support Dr. Andrew Wakefield, accessed 31 January 2011

- ↑ See: Martin J Walker, [http://www.rescuepost.com/files/fitzpatrick.pdf Brave New World of Zero Risk: Covert Strategy in British Science Policy], Slingshot Publications, September 2005.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick interview, 'Change4Life or life for a change?', WORLDbytes, accessed 5 March 2015

- ↑ See Dr Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second opinion: Domestic violence - NOT a healthcare issue', LM 118, p. 43, March 1999.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The rise of a pseudo-scientific links lobby: Every day there seems to be a new study making a link between food, chemicals or lifestyle and ill-health. None of them has any link with reality', 24 January 2013, Spiked, accessed 5 March 2015.

- ↑ For example, see Michael Fitzpatrick 'Aids panic in disarray', Living Marxism, No. 45 - July 1992, p. 17.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, [http://web.archive.org/web/20000618184026/www.informinc.co.uk/LM/LM45/LM45_Aids.html ' Aids panic in disarray'], Living Marxism, No. 45 - July 1992, p. 17, accessed 9 March 2015.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The truth about the Birmingham Aids panic', Living Marxism, No. 46 - August 1992, p. 20, accessed 9 March 2015.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, [http://web.archive.org/web/20000618184026/www.informinc.co.uk/LM/LM45/LM45_Aids.html ' Aids panic in disarray'], Living Marxism, No. 45 - July 1992, p. 17, accessed 9 March 2015.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, [http://web.archive.org/web/20000618184026/www.informinc.co.uk/LM/LM45/LM45_Aids.html ' Aids panic in disarray'], Living Marxism, No. 45 - July 1992, p. 17, accessed 9 March 2015.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, [http://web.archive.org/web/20000618184026/www.informinc.co.uk/LM/LM45/LM45_Aids.html ' Aids panic in disarray'], Living Marxism, No. 45 - July 1992, p. 17, accessed 9 March 2015.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Second Opinion: Domestic violence - NOT a healthcare issue', LM 118, p. 43, March 1999.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Doctoring the family', LM 98, March 1998, accessed 9 March 2015.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Doctoring the family', LM 98, March 1998.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Big girls and health zealots', LM 109, p. 33, April 1998.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Warning: Anti-tobacco crusades can damage your life', Living Marxism, No. 94 - October 1996, p. 16.

- ↑ Who study, debate, and publish reports on various cultural, social and economic issues, with an 'emphasis on the value of personal responsibility'. See 'About Us', Social Affairs Unit website, accessed November 2008

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Warning: Anti-tobacco crusades can damage your life', Living Marxism, No. 94 - October 1996, p. 16.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Exterminate the filthy smokers', LM 108, p. 37, March 1998, accessed 9 March 2015.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Child Sex Abuse: Who's really bad?', Living Marxism, No. 60 - October 1993, p. 16.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Child Sex Abuse: Who's really bad?', Living Marxism, No. 60 - October 1993, p. 16.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'Child Sex Abuse: Who's really bad?', Living Marxism, No. 60 - October 1993, p. 16.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The great mad cow panic', Living Marxism, No. 90 - May 1996, p. 24.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'A mad, mad, mad, mad world', Living Marxism, No. 80 - June 1995, p. 17.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'A mad, mad, mad, mad world', Living Marxism, No. 80 - June 1995, p. 17.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The great mad cow panic', Living Marxism, No. 90 - May 1996, p. 24.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The great mad cow panic', Living Marxism, No. 90 - May 1996, p. 24.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'A mad, mad, mad, mad world', Living Marxism, No. 80 - June 1995, p. 17.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The great mad cow panic', Living Marxism, No. 90 - May 1996, p. 24.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'A mad, mad, mad, mad world', Living Marxism, No. 80 - June 1995, p. 17.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The great mad cow panic', Living Marxism, No. 90 - May 1996, p. 24.

- ↑ Michael Fitzpatrick 'Inventing Disease', Risk of Freedom Briefing, Issue No. 12, July 2002, p.2.

- ↑ Data from Companies House, accessed 19 March 2011

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The enduring mystery of the ‘autism epidemic’', author biographical note, 27 October 2013, Autistica, accessed 9 March 2015.

- ↑ For approximate end date see: Michael Fitzpatrick, author archive, biographical note, Spiked, accessed 9 March 2015. This suggests he had retired by the 23rd of August, given that his last article for spiked was written at this time and his author biographical note indicates he was a retired GP.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick author archive, BJGP, accessed 5 March 2015.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, search results, Autistica, accessed 9 March 2015.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The enduring mystery of the ‘autism epidemic’', author biographical note, 27 October 2013, Autistica, accessed 9 March 2015.

- ↑ See Michael Fitzpatrick, 'The enduring mystery of the ‘autism epidemic’', author biographical note, 27 October 2013, Autistica, accessed 9 March 2015.

- ↑ See 'Reassessing the Enlightenment?', 30 October 2005, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See ‘Morbid Fascinations – our obsession with death’, 28 October 2006, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See ‘Playing Balls – why are men becoming obsessed with their health?’, 28 October 2006, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See ‘Post Ideology’, 28 October 2007, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See ‘Frederick Engels’, 28 October 2007, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See ‘Boozy Britain’, 2 November 2008, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See ‘Age of Autism: rethinking 'normal, 12 October 2009, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See ‘Is the NHS institutionally ageist?’, 1 November 2009, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See ‘The war on alcohol: new puritanism or healthy sobriety’, 30 October 2010, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See ‘Your mind, your high: is recreational drug use morally wrong?’, 29 October 2011, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See ‘Can social democracy survive the 21st Century?’, 30 October 2011, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See ‘Atheism: What's the point?’, 21 October 2012, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See ‘The law's drug problem: the challenge of legal highs’, 15 November 2012, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See 'Do as I say not as I do: what's wrong with hypocrisy?', 19 October 2013, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See 'What is addiction?', 19 October 2013, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See ‘Science journalism: the tyranny of evidence?’, 20 October 2013, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015

- ↑ See 'The science of public health: where’s the evidence?', 19 October 2014, Battle of Ideas, accessed 27 January 2015