International Institute for Strategic Studies

The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) describes itself as 'the world's leading authority on political-military conflict.Based in London, IISS is registerd as charity in UK, US and Singapore. Founded in 1958 the IISS has strong establishment links, with former US and British government officials among its members. The Foreign Office contributed £100,000 towards the setting up of its headquarters in central London, and the opening was attended by Thatcher and Lord Robertson of Port Ellen, then secretary general of Nato. Its early work focused on nuclear deterrence and arms control and was by its own account "hugely influential in setting the intellectual structures for managing the Cold War."[1]

Contents

Origins and history

Initially known just as the Institute for Strategic Studies, IISS was launched in November 1958 with the intension that it would be, as The Economist put it, ‘a Chatham House for Defence’.[2] It was incorporated as a limited company and a registered charity on 20 November 1958. Its launch was announced on 27 November 1958. Reporting on it’s launch a day later The Guardian headline read, ‘Institute for Defence Study, British Members, U.S. Finance’.[3]

The British members

The ‘British members’ were a collection of 20 politicians, journalists, academics, and former military men; as well as a few figures from the Church of England. The key founders were members of a Chatham House group which was studying disarmament issues.[4] They produced a Chatham House pamphlet On Limiting Nuclear War. The pamphlet had been put together by Pat Blackett, a Nobel physicist who had advised the UK government on ‘operational theory’ (e.g. game theory); Denis Healey, then Labour spokesman on Foreign Affairs; Richard Goold-Adams, a businessman and a journalist with The Economist; and Rear-Admiral Sir Anthony Buzzard, the former head of Naval Intelligence. The men had developed connections in Washington, according to Healey the most important of which was Paul Nitze (the principal author of a highly influential secret National Security Council document NSC-68). They were also supported by US Senator Ralph Flanders and Dick Leghorn,[5] a former Pentagon planner whose company Itek developed and built the photographic system of the CIA's top secret Corona program of satellite reconnaissance of the USSR between 1960 and 1972.[6]

On Limiting Nuclear War attracted the attention of other figures in the UK, including those interested in the moral implications of nuclear war; a topic which had not been of any great concern to Healey and his friends. They subsequently organised a conference ‘The Limitations of War in the Nuclear Age’ at the London office of the Commission of the Churches on International Affairs. There it was agreed that they should establish a think-tank modelled on Chatham House, but focused solely on military-strategic issues. Pat Blackett, who was apparently too busy to be closely involved, was replaced by the Chatham House expert Professor Michael Howard who founded the Department of War Studies at Kings College London, and along with some figures from the Commission of the Churches on International Affairs, these men started putting together the personnel for the would be think-tank.[7]

The US finance

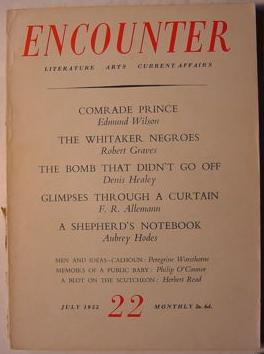

The ‘U.S. finance’ behind the new institute was a grant of $150,000 from the Ford Foundation to fund the institute for its first three years.[8] The International Affairs Division of the Ford Foundation which provided this funding was at that time headed by an important post-war propagandist called Shepard Stone. A former New York Times journalist, Stone had joined the Ford Foundation in 1952, prior to which he had worked as the Director of Public Affairs of the American High Commission in Germany. There his main task had been to channel secret payments to editors and journalists to ensure they propagated American interests.[9] At the Ford Foundation Stone worked with Joseph Slater who according to The Times was the driving force behind supporting the Institute.[10] Slater – who subsequently directed the Aspen Institute – had worked at the High Commission with Stone where both men had served under John J. McCloy, who was now chairman of the Ford Foundation. The aim of these former state propagandists was to win over Europeans who sought independence from Soviet and American control. According to one author, Stone hoped to ‘consolidate the Atlantic alliance, above all by abolishing the weak link in the West’s armory - the “neutralists,” those intellectuals who were disaffected by the Soviet Union but who were unwilling to align themselves with the United States’.’[11] Interestingly a concern with "neutralists" was shared by Healey. The group behind On Limiting Nuclear War had formed as a result of an article Healey had written in (the CIA funded) Encounter in July 1955 entitled The Bomb that Didn't Go Off. In it he had expressed concern about 'signs that Western Europe is slowly slipping into the sort of apathy about defence in which neutralism breeds.'[12]

On 27 October 1957 Healey was at a Bilderberg meeting in the Italian spa of Fiuggi. There he approached Shepard Stone to ask for a £1,000 to continue the distribution of American articles among his associates. Stone replied that the Ford Foundation would not provide anything less than $100,000.[13] Healey returned to London and drafted the application and the Ford Foundation duly granted $150,000.

The first director

The British man who was appointed to head this operation was Alastair Buchan, the diplomatic and defence correspondent of The Observer. His father John Buchan was a novelist, barrister and MP who had worked for the British War Propaganda Bureau during the First World War, as well as a war correspondent for The Times.[14] Alastair Buchan was an Old Etonian and Oxford graduate who had worked as assistant editor of The Economist from 1948 to 1951[15] when he became the Washington correspondent for The Observer. In Washington Buchan had made ‘a wide range of contacts in American political, academic and journalistic circles which were to prove a valuable asset when he became the first Director of the Institute’.[16] As head of the Institute Buchan developed a reputation for being ‘one of the few Englishmen who can “make himself at home” in the Pentagon’.[17]

The moral question disappears

The Institute had been founded at least partly on the ethical concerns raised by the nuclear arms race; as suggested by the involvement of several church figures. However, the ethical dimension to the Institute’s work proved to be dead at birth. Professor Michael Howard, one of the key figures behind the Institute later recalled that:

Although Kenneth Grubb remained chairman of our council and Alan Booth our secretary [both of whom were involved in the Commission of the Churches on International Affairs], we quickly found that we could not sustain our obligation to study both the political and the moral dimensions of our subject, as had been our intension.[18]

This development is not all that surprising when you consider the makeup of the Institute's founding Council. Whilst it included Pat Blackett and several churchmen who seemed genuinely concerned with disarmament, it also included several military figures as well as representatives from the arms trade. Anthony Buzzard and Lord Weeks both worked at the private arms company Vickers which were a major customer of the Ministry of Supply, where another Council member John Eldridge worked as Controller of Munitions from 1953 to 1957.[19]

Early years

The Institute initially had a ‘tiny staff’ and was based at ‘rather dingy offices off the Strand’[20] at 18 Adams Street which the Institute rented off the Royal College of Arts. Though dingy they were close to Britain’s major centres of power. As one founding member later recalled, they were ‘conveniently situated between Fleet Street and Whitehall.’[21]

There the Council held an evening reception on 17 February 1959 to mark the inauguration of the Institute. The reception was attended by several foreign diplomats and British military figures, as well as government Ministers.[22]

Encouraged by the presence of the Marshal of the RAF Sir John Slessor on the Institute's Council, numerous senior military figures became members. Figures from Whitehall also joined, encouraged by Michael Palliser, who was then head of the Policy Planning Staff in the Foreign Office.[23]

The Institute initial focus was on the publication of its annual report on the Soviet and NATO military build-up, which it called The Military Balance. Reporting on the publication of the first issue The Times wrote: 'The sources on which the institute have based their estimates are not given, but they appear to be authoritative. There is however one estimate - that Russia still maintains 175 effective divisions - which is very doubtful. This figure has been used by N.A.T.O for so long as a stick to encourage their members to increase their contributions to the shield force that its accuracy is suspect'.[24] In fact it was privately pointed out to Buchan by a CIA man who had joined the Institute that this first issue was ‘replete with errors, having been put together from published sources of widely varying reliability’. Buchan therefore made a point of checking each publication with the British government.[25] Precisely which section of the British Government was consulted is not clear, but in his memoirs Michael Howard refers to 'shadowy figures who furnished us with the information that made it possible to provide the statistics that gave The Military Balance...credibility from the beginning.'[26]

The Institute also published its quarterly magazine Survival which IISS still publishes today.

In 1959 The Instiute recruited Hedley Bull to act as a rapporteur. Bull, who was then an assistant professor at LSE, had just returned from a two year visit to 'the main centres in the USA of new thinking about arms control' - funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. Bull worked at The Institute between 1959-60 and produced a book The Control of the Arms Race (1961).[27] In 1965 he was appointed by Harold Wilson to head a new Foreign Office research unit on arms control and disarmament.[28]

In 1959 the Institute also published a book by the military historian and former Intelligence Corps officer Michael Richard Daniel Foot which included a foreword by Alastair Buchan.

In 1962 The Institute published The Spread of Nuclear Weapons, which was the first serious book-length study of nuclear proliferation. It was co-authored by John Maddox and Leonard Beaton the defence correpondent of The Guardian. Beaton had been in touch with The Institute since its start and in 1963 he became the Institute's first designated director of studies. After two years he gave up the post to become a senior research associate, freer to concentrate on his own work.[29]

In 1965 the Institute was awarded another $550,000 by the Ford Foundation and it announced that it would expand its staff, ‘particularly by recruiting from the Commonwealth, and the United States and Europe and…will become a private international organization’.[30] In May 1966 the Institute added International to its name and became the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Under Francois Duchene

In 1969 Buchan left the Institute and was replaced as Director by Francois Duchene who headed IISS until 1974. Duchene like Buchan was a former journalist at The Economist, and he had also worked as a Fellow at the Ford Foundation for two years immediately prior to his appointment.[31] He had also worked in military intelligence during his national service and was posted to Austria in 1948, then a hub of post-war espionage.[32]

Activities

Selling the Iraq War

IISS played a key role in furnishing the pretexts for the invasion of Iraq by publishing a dossier on Iraqi WMDs, on 9 September 2002, which was edited by Gary Samore, formerly of the US State Department, and presented by Dr John Chipman, a former Nato fellow.

- The dossier was immediately seized on by Bush and Blair administrations as providing "proof" that Saddam was just months away from launching a chemical and biological, or even a nuclear attack. Large parts of the IISS document were subsequently recycled in the now notorious Downing Street dossier, published with a foreword by the Prime Minister, the following week.[33]

Unlike the British Government, IISS later claimed it made mistakes in its dossier about the extent of the Iraqi threat. It commissioned an independent assessment by Rolf Ekeus, a former head of United Nations arms inspectors in Iraq. Samore and Chipman now claim their dossier had caveats about Iraq's supposed WMD arsenal which the Government insisted on removing from intelligence assessments - leading to "sexing up" accusations.[34] However, in his interview with BBC on the day of the publication of the report, such caveats are conspicuously absent. [35]

Pushing the bombing of Iran

In April 2006 The Institute was involved in briefing the media in which the BBC reported that Iran was 'on course' to develop nuclear weapons in 'three years'. On being challenged the Institute backed down slightly.[36] On 12 September 2007, IISS once again suggested Iran could have a nuclear weapon by 2009-2010, an estimate which is shared neither by the IAEA or US intelligence. It also went on to issue unsubstantiated warnings of a threat from a new and deadlier al-Qaida.[37]

Funding

For its first 30 years IISS received no government funded and was supported by American foundations with an interest in maintaining US hegemony over its European allies.

The Institute was founded on an initial donation of $150,000 from the Ford Foundation to fund it for its first three years[38] and between 1959 and 1979 it received a further $1.4 million from the Ford Foundation.[39]

The Rockefeller Foundation also provided funding in the Institute's early years, reportedly donating £3,500 in 1960[40] and £44,600 in 1964.[41]

In 1979 IISS sought government funding for the first time in order to support its move from its Adam Street offices to ‘a four-floor building on one of the many corners of Tavistock Street’. According to the Institute the funds were provided by “democratic governments”.[42] Later when IISS again moved offices to its current location at Arundel House it reportedly received £100,000 from the Foreign Office.[43]

In 1981 IISS received $2.5 from the Ford Foundation towards the setting up of a capital fund.[44]

In 1985 the MacArthur Foundation donated $200,000 to IISS.[45]

Personnel

Table of Founding Members

| Name | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Richard Goold-Adams | Chairman of the Council | Writer and Broadcaster |

| Lord Salter | Vice Chairman of the Council | Politician and university professor |

| Pat Blackett | Hon. Treasurer | Professor of Physics, Imperial College of Science, London |

| Alastair Buchan | Director | Journalist at The Observer |

| H.E.B. Jenkinson | Secretary of the Institute | Retired Royal Navy Commander |

| Kenneth Grubb | Council Member | Chairman, Commission of the Churches in International Affairs |

| Alan Booth | Council Member | Secretary, Commission of the Churches on International Affairs |

| Anthony Buzzard | Council Member | Director of Vickers-Armstrong Ltd., Director of Naval Intelligence 1951-1954 |

| Ronal Ivelaw Chapman | Council Member | Air Chief Marshal and Vice Chief of the Air Staff 1953-1957 |

| John Eldridge | Council Member | Comptroller of Munitions, Ministry of Supply 1953-1957 |

| Kurt Hahn | Council Member | Formerly Headmaster of Gordonstoun and Salem Schools |

| B.H. Liddel Hart | Council Member | Historian and Military Analyst |

| William Hayter | Council Member | Warden of New College, Oxford; British Ambassador to Moscow 1953-1957 |

| Denis Healey | Council Member | Vice Chairman of the Foreign Affairs Group, Parliamentary Labour Party |

| Michael Howard | Council Member | Lecturer in War Studies, Kings College, London |

| James Hutchison | Council Member | President of the Assembly of Western European Union, 1957-1958 |

| John Slessor | Council Member | Chief of the Air Staff 1950-1952 |

| Henry Tizard | Council Member | Chairman, Advisory Council on Scientific Policy and Defence Research Policy 1946-1952 |

| Donald Tyerman | Council Member | Editor of The Economist |

| H.M. Waddams | Council Member | Secretary, Foreign Relations Council of the Church of England |

| Lord Weeks | Council Member | Deputy Governor of the British Zone of Germany 1945; Chairman of Vickers Ltd. |

| Montague Woodhouse | Council Member | Director General of The Royal Institute for International Affairs since 1955 |

Directors

Alistair Buchan, 1958-1969 | Francois Duchene | John Chipman

Current personnel

Principals

François Heisbourg - Chairman | Fleur de Villiers - Chairman of the IISS Executive Committee | Thomas Seaman - Honorary Treasurer and Investment Committee Chairman | Peter Stormonth Darling - Audit Committee Chairman | John Chipman - Director-General and Chief Executive | Michael Draeger - Company Secretary

President, President Emeritus and Vice-Presidents

Michael Howard - President-Emeritus | Robert Ellsworth - Vice-Presidents | Michael Palliser - Vice-Presidents | Yoshio Okawara - Vice-Presidents

The Council

Hironori Aihara | Ross Babbage | Carl Bildt | Dennis C. Blair | Thérèse Delpech | Fleur de Villiers | Lord Guthrie of Craigiebank | Rita E Hauser | François Heisbourg | David Ignatius | Roy MacLaren | Kishore Mahbubani | Moeletsi Mbeki | Edwina Moreton | Pauline Neville-Jones | Günther Nonnenmacher | Thomas Pickering | Lord Powell of Bayswater | V R Raghavan | Michael D. Rich | Adam Roberts | Yukio Satoh | Thomas Seaman | Lilia Shevtsova | Robert Wade-Gery | Theodor Winkler

Other associates

Peter Ackerman Visiting Fellow in 1990 | Yonah Alexander | Brenda Stern

Contact, resources and notes

Contact

- Arundel House

- 13–15 Arundel Street, Temple Place

- London WC2R 3DX

- Tel: +44 (0) 20 7379 7676

- Fax: +44 (0) 20 7836 3108

Resources

Notes

- ↑ IISS About us

- ↑ The Economist, 29 November 1958

- ↑ The Guardian, 28 November 1958

- ↑ Captain Professor The Memoirs of Sir Michael Howard Page 158

- ↑ Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (London: Penguin, 1989) p.236

- ↑ 'Leghorn to Receive Special Vanguard for His Efforts in Founding CableLabs', Reuters, 31 March 2008

- ↑ Captain Professor The Memoirs of Sir Michael Howard Page 158

- ↑ ‘Strategic Studies Institute Formed. Mr. Alastair Buchan First Director’, The Times, 28 November 1958; pg. 6; Issue 54320; col F

- ↑ David M. Oshinsky, ‘Bagman for Democracy ‘,New York Times, 15 July 2001

- ↑ The Times, 13 November 1967; pg. 5; Issue 57097; col E

- ↑ John Krige, American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe (MIT Press, 2006) p.174

- ↑ Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (London: Penguin, 1989) p.237

- ↑ Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (London: Penguin, 1989) p.239

- ↑ National Archives Famous names in the First World War John Buchan MP

- ↑ ‘At Home in the Pentagon’, The Times, 16 December 1967; pg. 6; Issue 57126; col F

- ↑ ‘Obituary: Professor the Hon Alastair Buchan Founder of the International Institute for Strategic Studies’, The Times, 5 February 1976; pg. 16; Issue 59620; col E

- ↑ The Times, 16 December 1967; pg. 6; Issue 57126; col F

- ↑ Captain Professor The Memoirs of Sir Michael Howard Page 158

- ↑ Institute Press Release, 28 November 1958

- ↑ ‘Obituary: Professor the Hon Alastair Buchan Founder of the International Institute for Strategic Studies’, The Times, 5 February 1976; pg. 16; Issue 59620; col E

- ↑ Captain Professor The Memoirs of Sir Michael Howard Page 158

- ↑ The Times, 18 February 1959; pg. 12; Issue 54388; col A

- ↑ Michael Howard, Captain Professor The Memoirs of Sir Michael Howard (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006) p.162

- ↑ 'Russia Reported To Have "100 Main Missile Bases"', The Times, Thursday, Dec 03, 1959; pg. 12; Issue 54634; col C

- ↑ Raymond L. Garthoff, A Journey Through the Cold War: A Memoir of Containment and Coexistence (Brookings Institution Press, 2001) p.63

- ↑ Michael Howard, Captain Professor The Memoirs of Sir Michael Howard (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006) p.162

- ↑ Adam Roberts, ‘Bull, Hedley Norman (1932–1985)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 29 July 2008

- ↑ 'Arms Control Unit', The Times, Friday, Jan 01, 1965; pg. 10; Issue 56208; col F

- ↑ Peter Lyon, ‘Beaton, (Donald) Leonard (1929–1971)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 29 July 2008

- ↑ ’Grants to British Study Groups’, The Times, 15 February 1965; pg. 8; Issue 56246; col C

- ↑ ‘Obituary: Francois Duchene’, The Independent, 25 July 2005

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Kim Sengupta, Iraq Occupation Made World Less Safe, Pro-War Institute Says Studies , The Independent, May 26, 2004

- ↑ Kim Sengupta, Iraq Occupation Made World Less Safe, Pro-War Institute Says Studies , The Independent, May 26, 2004

- ↑ BBC Interview with John Chipman, 9 September 2002

- ↑ The BBC, Iran and the Bomb The Cat's Blog, Wednesday, April 12, 2006

- ↑ Richard Norton-Taylor,Al-Qaida has revived, spread and is capable of a spectacular The Guardian, September 13, 2007

- ↑ ‘Strategic Studies Institute Formed. Mr. Alastair Buchan First Director’, The Times, 28 November 1958; pg. 6; Issue 54320; col F

- ↑ Richard Magat, The Ford Foundation at Work, 1979 p.112

- ↑ The Times, Wednesday, Oct 26, 1960; pg. 10; Issue 54912; col D

- ↑ The Times, Monday, Aug 17, 1964; pg. 10; Issue 56092; col E

- ↑ The Times, 18 December 1979; pg. 12; Issue 60503; col C

- ↑ Kim Sengupta, ‘Occupation made world less safe, pro-war institute says’, The Independent, 26 May 2004

- ↑ Ford Foundation Annual Report 1981 p.33

- ↑ Henry Gottlieb, ‘Foundation Offering $25 Million for War and Peace Research’, The Associated Press, 24 January 1985