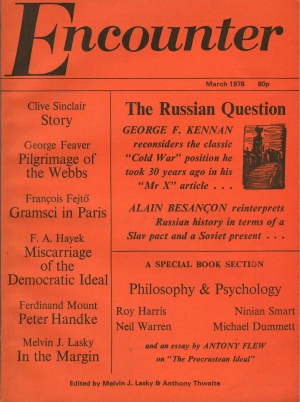

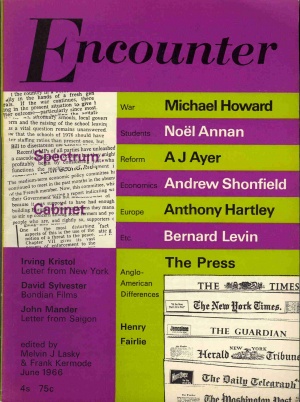

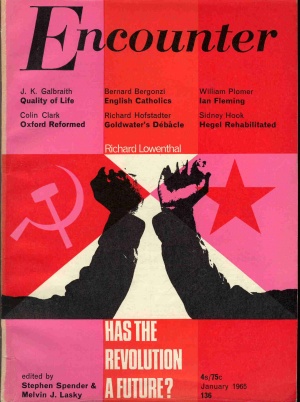

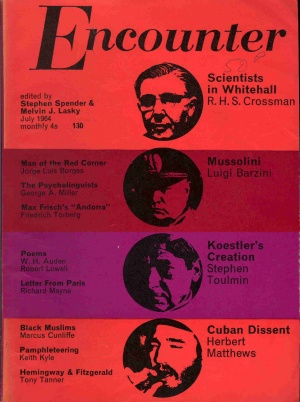

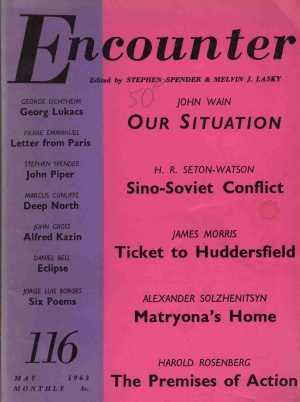

Encounter

Encounter was a literary magazine, founded in 1953 by poet Stephen Spender and the neoconservative Irving Kristol. It was largely an Anglo-American intellectual and cultural journal, published in England. The magazine ceased publication in 1990. Spender was an editor until 1967, when he resigned.[1] The cause of Spender's resignation was the revelation in 1967 of the covert CIA funding of the magazine, of which he had heard rumours, but which he could not confirm.[2] This caused a scandal among European and American intellectuals, and has, ever since, somewhat overshadowed the magazine's literary content.[3]

Thomas W. Braden, who headed CIA IOD's operations between 1951 to 1954, said that the money for the magazine "came from CIA, and few outside the CIA knew about it. We had placed one agent in a Europe-based organization of intellectuals called the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Another agent became an editor of Encounter."[4]

Encounter was most popular in terms of readership and influence under Melvin J. Lasky, who succeeded Kristol as Editor in 1958, and would serve as the main editor until the magazine ceased to publish. Other editors in this period included Frank Kermode and D. J. Enright.[5]

Giles Scott-Smith [6]argues that the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) arose at a time when the traditional position of the autonomous critical intellectual was under threat from the demands of political conformism in the east and west, and was in a sense a response to these conditions, but he also argues this from Gramsci's notion of the role of the 'intellectual' within the construction and maintenance of hegemony:

- "This recognises cultural-intellectual activity as essentially connected to, and crucially involved with, the material conditions of society." [7]

'Encounter' was funded through the CCF during the cold war as part of the US (and British government's) secret programme of cultural propaganda in Western Europe in the 50s and beyond. Managed by the recently formed CIA, the CCF, run by CIA agent Michael Josselson from 1950-1967, was the cultural counterpart of the Marshall Plan and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forging the transatlantic consensus through which American hegemony operated.

The 'Partisan Review,' (PR) with its anti-Stalinism, became noticed by the US State Department in mid-1947, Edited by Sidney Hook and former Trotskyite James Burnham, it had been funded by CIA conduit the Farfield Foundation which had provided $1500. Left to continue its own policy, it did provide a kind of blueprint for what would be attempted on a wider scale with the CCF's own magazines, such as Encounter, Preuves (France), Tempo Presente (Italy), Cuardenos (Spain), Quest (India), and Quadrant (Australia), where editorial lines were kept within the strategic boundaries of anti-communism. Above all, it was PR's quality and ability to act as a mouthpiece for a particular section of the intellectual community that made it a benchmark for later attempts by the Congress to do the same.[8]

Studies of the history of Encounter, such as Scott-Smith's indicate that CIA funds were not the cause of the magazine's anti-communist, pro-American orientation, merely a materially-supporting factor.

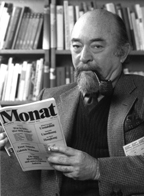

Lasky

Melvin Lasky, a journalist with both PR and New Leader and eventually editor of Encounter, was also a key figure in arranging the formation of the CCF. Moving easily between intellectual, political, and intelligence circles, he proposed the creation of a sophisticated literary-political journal to promote the idea that American power was there to protect European cultural and intellectual freedom: 'to overcome the obstructions which anti-American forces in Europe have been relentlessly preparing to block the US position in world affairs - first and foremost, on the issue of the Marshall Plan for continental reconstruction.' [9]

This produced 'Der Monat', which first appeared in October 1948 with Lasky as chief editor. According to Scott-Smith:

- "Der Monat is a good example, perhaps better than the more deliberate strategy of Encounter later, of the collusion of intellectual and political interests in the West in this period. The defence of cultural values and cultural expression in a free society that this journal stood for was inseparable from the anti-communist Cold War strategy that was rapidly emerging as the dominant theme of Western geopolitics. What is also significant about Der Monat is that Lasky was able to seize the initiative so quickly at a time when the demands for a more aggressive cultural foreign policy were just beginning to gather strength in Washington. Lasky's position can be summed up in a letter to Nabokov a few years later - 'I wish we didn't have to go around trying to make "Propaganda Kapital" out of everything, especially the arts; but I'm afraid we do.'

The disillusionment with communism in general and Stalinism in particular amongst key figures of the European Left was important to Lasky at this time - particularly the group around The God that Failed.

In an extended essay in a September 1967 issue of The Nation. Writing just a little over a year after reports surfaced of CIA involvement in the CCF Christopher Lasch responded to CCF claims that the CIA had no effect on its work with this analysis of the American academic intellectual:

- Professional intellectuals had become indispensable to society and to the state (in ways which neither the intellectuals nor even the state always perceived), partly because of the increasing importance of education—especially the need for trained experts—and partly because the Cold War seemed to demand that the United States compete with communism in the cultural sphere as well as in every other. The modern state, among other things, is an engine of propaganda, alternately manufacturing crises and claiming to be the only instrument which can effectively deal with them. This propaganda, in order to be successful, demands the cooperation of writers, teachers, and artists not as paid propagandists or state-censored time servers but as “free” intellectuals capable of policing their own jurisdictions and of enforcing acceptable standards of responsibility within the various intellectual professions. [...] A system like this presupposes two things: a high degree of professional consciousness among intellectuals, and general economic affluence which frees the patrons of intellectual life from the need to account for the money they spend on culture. Once these conditions exist, as they have existed in the United States for some time, intellectuals can be trusted to censor themselves, and crude “political” influence over intellectual life comes to seem passé."[10]

Alan Johnson[11] states that in his later 1969 essay, "The Cultural Cold War: A Short History of the Congress for Cultural Freedom," Lasch argued that choosing the demigod 'the West' stilled the criticism of the men who presided over the West arguing it had "consistently approved the broad lines and even the details of American policy."

Johnson argues that 'Who Paid The Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War' by Frances Saunders main charge against the CCF was precisely that "the natural procedures of intellectual enquiry" were distorted by this new relationship to the state. He also adds that

- "Saunders traces the CIA's role in funding the European Youth campaign, and those European political factions — such as the British "revisionists" around Gaitskell — who were moving closer to the idea of a united Europe linked to a democratic capitalist America. Jay Lovestone's role at the heart of this European operation is made clear. The smoking gun that shows the CIA funded the British Fabian Society journal, Venture, is here, alongside the claim that Denis Healey fed information about Labor Party members and trade unionists to the Information Research Department at the British Foreign Office. When the Labor Party beat the Conservatives in the 1964 general election, Michael Josselson, the CIA agent in the CCF wrote to Daniel Bell, "We are all pleased to have so many of our friends in the new government.""

The British Information Research Department (IRD) had been set up in the late 40s.

Further Reading

- Frances Stonor Saunders, 'How the CIA plotted against us', New Statesman, 12 July 1999

- Robert Griffith The Cultural Turn in Cold War Studies

- Andrew Roth, Obituary: Melvin Lasky: Cold warrior who edited the CIA-funded Encounter magazine, Guardian, 22 May 2008

References

- ↑ A Short Biography of Sir Stephen Harold Spender, accessed 24 June 2008.

- ↑ 'Stephen Spender Quits Encounter', New York Times, 8 May 1967

- ↑ 'Obituaries: Sir Stephen Spender', Peter Porter, The Independent, 18 July 1995

- ↑ Thomas W. Braden, 'I'm glad the CIA is "immoral"', The Saturday Evening Post, 20 May 1967

- ↑ 'Sir Frank Kermode Papers, 1951-2006: Finding Aid', Princeton University Library, accessed 24 June 2008

- ↑ Giles Scott-Smith (2002) The Politics of Apolitical Culture: The Congress for Cultural Freedom, the CIA and Post-War American Hegemony, London: Routledge.

- ↑ Scott-Smith (2002:13)

- ↑ Giles Scott-Smith (1998) 'The Organising of Intellectual Consensus: The Congress for Cultural Freedom and Post-War US-European Relations', Lobster 36.

- ↑ Giles Scott-Smith (1998) 'The Organising of Intellectual Consensus: The Congress for Cultural Freedom and Post-War US-European Relations', Lobster 36, quoting 'On the Need for a New Overt Publication, Effectively American-Oriented, on the Cultural Front', 7th December 1947; 'Towards a Prospectus for the "American Review"', 9th December 1947.

- ↑ Christopher Lasch (1967) 'The Agony of the American Left', The Nation. Quoted from http://bostonreview.net/BR29.5/kodat.html

- ↑ Alan Johnson (2001) 'The Cultural Cold War: Faust Not the Pied Piper', New Politics, Vol. 8 No. 31