National Domestic Extremism Unit: organisational history

|

This article is part of the Counter-Terrorism Portal project of SpinWatch. |

This article is part of the Undercover Research Portal at PowerBase - investigating corporate and police spying on activists.

See the main page at National Domestic Extremism Unit

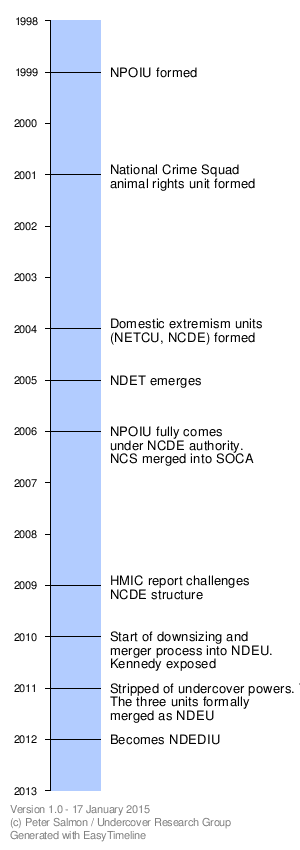

This page looks at the organisational history of the national domestic extremism units in the United Kingdom. In particular, the National Domestic Extremism Unit refers to a specialist police organisation that began life as the National Coordinator for Domestic Extremism (NCDE),[1] and was subsequently renamed the National Domestic Extremism Unit (NDEU) and more recently the National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit (NDEDIU). For much of its history it was controlled by the Association of Chief Police Officers' Terrorism and Allied Matters Committee, before being transferred to the the Metropolitan Police Service's Counter Terrorism Command in the wake of the Mark Kennedy undercover scandal.

During its time under the control of ACPO, the NDEU consisted of a group of police units, several of which have gained national attention for their role in the policing of protests and deployment of undercover police into political and activist movements. These units were the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU), National Extremism Tactical Coordination Unit (NETCU), National Domestic Extremism Team (NDET).[2] Many began as separate units, or created out of the merger of smaller units around the UK. It was a sub-unit of the NPOIU, the Confidential Intelligence Unit, which ran a number of infiltrators that targeted protest movements.

Other detailed pages on the domestic extremism units:

Contents

Background to creation of the unit

Much of the impetus for the domestic extremism units came from the resurgence of militant animal right campaigning in the late 1990s and 2000s, particularly targeting the animal testing laboratory Huntingdon Life Sciences in Cambridgeshire and a new biotech laboratory in Oxford. Up to this point, activists were generally referred to as 'Animal Rights Extremists' by the police and press and in Parliamentary debates, with militant environmental campaigning being referred to as 'ecoterrorism' rather than extremism.[3]

Up until then much of the intelligence gathered on them was through regional forces Special Branch units which were expected to:[4]

- gather intelligence on animal rights extremist activity and seek to prevent attacks on persons and property targeted by such extremists

This material would then be feed into the Animal Rights National Index, another Special Branch project that subsequently became associated with the National Criminal Intelligence Service.[5]

Pre 2004: National Crime Squad

In 2001 a unit was set up within the National Crime Squad (NCS) to target animal rights activists, particularly those campaigning against vivisection laboratories using flying pickets[6]; this was apparently accompanied by the creation of a high-level ministerial committee[7] (the Ministerial Committee on Animal Rights Extremism which looked at policy and legislative changes to tackle animals rights campaigns[8]). The otherwise unnamed NCS unit was involved in the arrests of 29 animal rights activists in October 2001, on the grounds of fraud.[9] At the time, the officer overseeing its work appears to have been Assistant Chief Constable Neil Giles,[10] the head of the eastern operations section of the National Crime Squad, and 'a specialist in covert operations' according to his biography.[11]

In 2002, Home Office minister John Denham reported in a written answer to Parliament:[8]

- The National Crime Squad has undertaken a number of operations which have resulted in the arrest of 70 individuals for a variety of offences relating to animal extremism, and has supported colleagues nationally in the co-ordination of both intelligence and operational activity.

However, it was noted by government minister Caroline Flint two years later in 2004, responding to the work of the squad on targeting animal rights, that:[12]

- The National Crime Squad provides specialist support and assistance to police forces. It is, however, individual police forces that lead on investigations within their areas, including investigations into the activities of animal rights extremists.

The National Crime Squad animal rights unit appears to have continued playing a role into 2004, when it was mentioned in conjunction with the subsequent domestic extremism units and, according to press reports, had been targeting the leading organisers of animal rights protests.[13][14] The National Crime Squad itself was merged with other units to form the Serious Organised Crime Agency on 1 April 2006.[15] It is likely that the animal rights unit within it had been disbanded or merged into the domestic extremism units by this stage, if that had not already happened in 2004.[16]

2004: Creation of domestic extremism units

In 2004, with activist momentum still on the increase following several notable victories, there was strong criticism from the pharmaceutical industry that not enough was being done to tackle the issue, particularly that of Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty and associated groups. [17] This was accompanied by threats to pull significant amounts of funding from the UK, including from GlaxoSmithKline.[18] and Novartis.[19] A number of high ranking meetings with Government followed, including a notable one between then Prime Minister Tony Blair and the pharmaceutical industry at a private event in Oxford University.[20]

This pressure resulted in the Home Office July 2004 report 'Animal Welfare - Human Rights: protecting people from animal rights extremists'.[21] This document sets out the government's planned strategy 'for countering animal rights extremism'. In it, it notes the creation of both NETCU and the appointment of Anton Setchell (though not by name):

- In addition an Assistant Chief Constable has been appointed to be responsible for the operational co-ordination of investigations and to develop a new national framework for tackling extremism. This new policing strategy and national framework pulls together the action which the police together with criminal justice agencies such as CPS are taking to tackle this problem. In particular, the police will identify best practice and define national standards in all areas of prevention, initial response and investigations into criminal activity by extremists.

In the context of the document and from government statements,[22] it is clear that the initial impetuous to create a national response was focused on the animal rights movement. Press from the time note his appointment as national coordinator 'to lead a new offensive against animal rights protestors' provided with a team to build cases resulting in the prosecution of said protestors. Previously he had organised the policing of animal rights protests against plans to build a new animal laboratory by Oxford University.[23]

It is only at a later period that Setchell takes the title of National Coordinator Domestic Extremism. This is presumably as his unit develops its focus beyond animal rights to take in other protest movements when it takes over the National Public Order Intelligence Unit, which already had this remit.

2005-2011 - NCDE: Consolidation and expansion

Organisational structure

It is to be noted that initially the units involved were all independent of each other, though NCDE drew on the knowledge and experience of NETCU. The intelligence link was to come from NPOIU, then located within Metropolitan Police’s Special Branch. However, due to problems with protocol, NPOIU would only pass on intelligence to other Special Branch officers / units. Thus, initially the NCDE developed his own intelligence cell as part of NDET, while NETCU created special reporting procedures for local forces to collect details of animal rights related activities to improve the overall picture. [17] In 2006, the three units were finally aligned under the National Intelligence Model[17] and brought together under the control of the NCDE,[24] with Setchell becoming head of NPOIU. [17] As such they worked on both extremism and public order, [24] which may have helped facilitate the extension of its original mission from focusing on animal rights to ‘domestic extremism’ as a whole, based on the relationship between protest groups being active through marches and other demonstrations.[25]

By the end of the reorganization, the roles of NPOIU, NETCU and NDET under the NCDE was intelligence, prevention and enforcement respectively, while ‘their core role is provide support and advice to police forces that remain responsible for intelligence, prevention and enforcement functions within their respective local force areas.’ [26]

While the NDCE and its units were funded primarily by the Home Office, it was independent of that department, and also worked with other departments such as the Department for Business, Innovation and Trade.[27]

Funding and staff

Understanding of the picture of funding is hampered by refusal by ACPO and the Home Office to answer questions on the funding,[28] as a result this overview is just a start.

Though the NCDE and related units were formed of police officers and came under the control of ACPO (TAM), they were not funded by individual police forces, but rather the Home Office, (which also provided the funding for the ACPO Terrorism and Allied Matters Committee.)[29]

Adding to the confusion is the fact that the individual units appear to have been funded separately. For example, NDET received £2m from the Home Office for the period 2009-10 (but none for subsequent years),[30] while the NPOIU grew from £2.6m in 2005/6 to £5.7m for 2009/10.[31].

When the units were merged as the NDEU and subsequently transferred to the Metropolitan Police, funding continued to come from the Home Office[32] through a Grant Agreement with the Metropolitan Police for the 2010/11 financial year, [24] domestic extremism having its own Home Office stream, separate from counter-terrorism funding. [33] At this point, the budget across all three units of the NDEU was £8.1 million covering 100 people (2/3 officers, 1/3 police staff). [27][34] By July 2014 this would appear to have grown to '300 London-based staff and 300 regionally-based including: MPS and seconded police officers, police staff, technical and social media experts'.[35]

Role of the National Coordinator Domestic Extremism

The head of the NCDE, the National Coordinator Domestic Extremism (NCDE -sometimes also given as NDEC) answered directly to ACPO's Terrorism and Allied Matters Committee. [36] According to an interview on 25 July 2009, he had no ‘executive authority or control’ over police forces, and his only oversight was by way of reporting to the TAM committee. [26]

By the end of January 2005 his responsibility was given as to 'oversee national investigations in this area of police work, including the work of local forces as well as that of National Extremism Tactical Co-ordination Unit (NETCU), the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU) and the National Crime Squad'.[36] [37]

This role of overseeing national investigations developed into control of NETCU and NPIOU by February 2007, along with the establishment of the National Domestic Extremism Team.[38]

By this point a press release from his office describes the Coordinator’s work as ‘to coordinate the police response to single-issue, domestic extremism’.[38] In 2012 it was described as providing ‘strategic support and direction to police forces dealing with domestic extremism investigations’.[24]

The NCDE's office was given as 10 Victoria Street, London, SW1H ONN, the ACPO headquarters and which building is home to a number of other police organisations and Home Office units.[39]

In December 2014, the Metropolitan Police confirmed that the role of NCDE was still existent and the title given to the head of the NDEDIU.[40]

Member Units

NETCU

NETCU was established in March 2004 by the Chief Constable of Cambridgeshire in response the animal rights campaign against Huntingdon Life Sciences[41] with Home Office funding and based out of Huntingdon. Initially it was part of the National Crime Squad.[42] Its responsibility was to act as an interface between police and those companies / institutions who were the subject of campaigns and protests, as well as supporting local police forces by producing guidance. It later extended its interest to other protests, particularly environmental. A similar unit, WETCU, was also established in Wales.

Much of the work of NCDE and NDEU was often attributed to NETCU by protestors; as the more public face of the various units, it attracted most attention, including monitoring by blogs such as NETCU-Watch.

- See also NETCU

NPIOU

The NPIOU was formed in 1999 as part of a national strategy within ACPO around public order issues, and funded by the Home Office, in particular:[43]

- it was established to support police forces in managing the intelligence around the threat to communities from public disorder connected to domestic extremism and single issue campaigning.

Its basis was the Animal Rights National Index,[44] and rooted within Special Branch,[45] through which it drew upon officers from the Special Demonstration Squad.[46] Pre-existing intelligence gathering units - the Northern Intelligence Unit and the Southern Intelligence Unit that had monitored travellers and protestors during the 1990s - were incorporated into it as satellite organisations. [47] Later its work was described as: [48]

- to reduce criminality and disorder from domestic extremism and to support forces in the way they dealt with strategic public order issues, including by gathering intelligence through the deployment of undercover officers.

It was charged with maintaining a database on protestors and activists, but early on it created a sub-unit, the Confidential Intelligence Unit (CIU) which ran infiltrators. It is known that undercover officer Mark Kennedy was deployed by CIU in 2002, but he is believed to have replaced an earlier officer, Rod Richardson who was active from 1999 to 2003.

- See also NPOIU

NDET

NDET was a unit of detectives set up in 2005[24] by ACPO to provide assistance - practical and intelligence - to police forces facing protests from 'domestic extremists', and to look at all crimes 'linked to single-issue type causes and campaigns'. The unit came to public attention when it lead the investigation into the letter bomber Miles Cooper[38] and was asked to assist the investigation into the hacking of the Climate Research Unit at University of East Anglia.[49] It also oversaw Operation Achillies under DCI Andy Robbins which investigated Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (see below). Later its purpose was listed as:[27]

- NDET is responsible for co-ordinating police operations and investigations against domestic campaigns and extremists, as well as identifying possible linked crimes across the country.

2011: Reorganisation and downsizing

In 2009 and 2010 a number of internal reports and two from HM Inspectorate of Constabulary (‘Adapting to Protest’ and ‘Counter Terrorism Value for Money’), highlighted an issue with weak governance and oversight.[41] It was decided that ACPO was no longer an appropriate home for the domestic extremism units, but would be better given to a lead force to manage, with arrangements similar to the national counter-terrorism network.[24] At the time the NDEU had a staff of about 100 and a budget of 8.1million.[50]

In January 2011, the Chief Constables Council of ACPO finalized the merging of the National Co-ordinator for Domestic Extremism and the three units under him into one unit- the National Domestic Extremism Unit (NDEU).[48][51][52] An early announcement of the reorganisation had appeared in November 2010[46], while DCS Adrian Tudway was appointed as the new NCDE - replacing Setchell who had been told to resign that month.[53]

The brief of the new unit did not changed much:[54]

- The NDEU supports all police forces to help reduce the criminal threat from domestic extremism across the UK. It works to promote a single and co-ordinated police response by providing tactical advice to the police service alongside information and guidance to industry and government...

One of the key responsibilities of the NDEU is to provide intelligence on domestic extremism and strategic public order issues in the UK.

The tasks included the continuation of handling 'intelligence related threats across force, national and international boundaries’ - inherited from the NPOIU [55] This task probably included utilizing undercovers abroad, such as Mark Kennedy and Marco Jacobs.

The merging of January 2011 involved a downsizing of the units, with the Head of NETCU, Steven Pearl, also being told to resign and budget cuts put in place.[53] Setchell's two successors as NCDE, Tudway and Greany (see below), were not given the rank with the ‘seniority of a chief officer’, [24] but held the lesser with rank of Detective Chief Superintendent.[56][50] Formal transfer of the units occurred on 1 June 2011.[57] In the wake of the downsizing, the three units under the NCDE had about 100 serving police officers and employees of police forces from across the UK.[34]

It is worth nothing that Mark Kennedy was initially exposed as an undercover in October 2010, but it did not make general headlines until the collapse of the Ratcliffe-on-Soar trial in January 2011. It was in response to this that the Minister for Police, Nick Herbert stated of the units that ‘it is clear to us all that operationally something has gone very wrong’, [58] and subsequently announced that the national domestic extremism units would lose their operational powers. [59] At the same time ACPO President, Sir Hugh Orde, spoke of there being a lack of ‘transparency accountability framework’ for the units, and HM Inspectorate of Constabulary announced there would be a review of the units by Bernard Hogan-Howe. [60]

However, it was admitted by the Home Office that the merger to form the NDEU was a re-branding exercise.[61] It retained its structure, and in his January 2011 statement, Nick Herbert, Minister for Police was still talking in terms of these units, particular NPOIU being the largest of the three.[60] The NPOIU in particular would continue to be mentioned as a distinct unit in the various reports that followed in the wake of Mark Kennedy, including that of the Surveillance Commissioner Sir Christopher Rose, several by the Inspectorate of Constabulary and the 2013/4 reports of Operation Herne. (Police documents themselves would refer to the NDEU as the ‘former NPOIU, adding some confusion.[62])

Transfer of control to the Metropolitan Police

While the reorganization was taking place, the future of the national domestic extremism units was under discussion in the light of the exposure of Mark Kennedy. Thus, on 28 January 2011, the Chief Constable's Council, the highest decision making body within ACPO, agreed to the transfer of the three national domestic extremism units to transfer to the Metropolitan Police (as lead force) with immediate effect.[63] The formal transfer of the NDEU units including 'the NCDE role, associated responsibilities and information held by those units' passed to the Metropolitan Police Service on 7 February 2011.[64] In particular, it was placed under the Metropolitan Police Service's Counter Terrorism Command[65][34] – also known as SO15, and which had previously been formed out of a merger of the Metropolitan Police’s Special Branch and Anti-Terrorism Branch. It remained headed by the National Coordinator for Domestic Extremism.[40]

Thus, the amalgamation of the units was already happening when it was announced that the combined unit would be transferred to the Metropolitan Police and lose its operational powers.

Following the transfer, the NDEU initially retained the intelligence collection, investigation support and awareness raising functions of its precursor units: [24]

- The focus for the work of the precursor units and for NDEU today concerns protest associated with extreme methods used in environmental protest, animal rights and violent political extremism. Other activity is also considered where emerging threats are identified, and where significant events create a unique opportunity for activists.

The NDEU‟s role covers both domestic extremism and public order policing. By way of example, the NDEU were involved in efforts to obtain and co-ordinate intelligence during the August 2011 public disorder, which originated in Tottenham and spread beyond London….

Recent national police activity supported by the NDEU includes preventing and / or bringing to justice a number of serious crimes, involving threats to life and harm to individuals, serious damage to property, and the acquisition of weapons such as firearms and homemade bombs.

This work was also summarized in another 2012 police report as: [66]

- The function of the NDEU is to collate, assess, develop and disseminate intelligence and intelligence products across all police forces of the UK in order to prevent and detect acts of domestic extremism and protest that cross over the legal threshold.

One of its subunits was the Strategic Threat Assessment, which was one of two police organisations identifying threats to public order. Listed as events which provided practical learning experiences for the policing of large scale disorder were the G20 protests, English Defence League demonstrations and the August 2011 riots, in all of which NDEU has played a role. [33]

Oversight of the NDEU was placed under Senior National Coordinator for Counter Terrorism.[24] The Head of NDEU, then reported through the head of the MPS’s Counter Terrorism Command to the Chair of the ACPO Terrorism and Allied Matters Business Area; while the unit continued to be funded by ACPO and the Home Office. [66] The ACPO Terrorism and Allied Committee continued to provide ‘the development of police service policy and strategy in respect of relevant counter terrorism, domestic extremism and other policing themes.’ [67]

Though now housed with the Metropolitan Police, it retained its national function, and had officers seconded from other forces, including, for example, two from West Yorkshire Police. [68]

Renamed to NDEDIU

In 1 May 2013 the NDEU was formally renamed the National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit (NDEDIU) [54] (though the name change was agreed by Chief Constable’s Council of ACPO on 1 October 2012[48]). In this period it was stripped of its ability to run undercover officers, [48] though it retained control of its database / intelligence gathering function (see below) and continued to lead investigations, most notably that leading to the imprisonment of SHAC activist Debbie Vincent in 2014.

All deployments of undercover officers were now to be coordinated either by the SO15 Special Project Team (SPT) or one of the regional SPTs run by North West, North East and West Midlands Counter Terrorism Units. [48]

Subsequently, the NDEDIU was organized into two units (following acceptance of the NDEU Business Development Plan for the Establishment of a National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit put forward in October 2012 agreed by ACPO’s Chief Constables Council in May 2012): [48]

- a) Protest and Disorder Intelligence Unit. This unit collates and provides strategic analysis relating to protest and disorder across the UK; and

- b) Domestic Extremism Intelligence Unit. This unit provides strategic analysis of domestic extremism intelligence within the UK and overseas.

Other Undercover Research sources

- National Public Order Intelligence Unit

- National Extremism Tactical Coordination Unit

- Association of Chief Police Officers (Terrorism and Allied Matters)

- Special Demonstration Squad

- Mark Kennedy

External Resources

- Britain's Secretive Police Force – Politicising the Policing of Public Expression in an Era of Economic Change (Paper Q2), electrohippies, April 2009.

To Do

- FOIA: ACPO minutes discussing its formation and remit.

- FOIA on Liddle's post and whether it is the same as Mark Rowley.

Notes

- ↑ As there is no consistent title for this position, with various official documents using 'National Coordinator Domestic Extremism’, ‘National Coordinator - Domestic Extremism’, ‘National Coordinator of Domestic Extremism’, 'National Coordinator, Domestic Extremism' or 'National Coordinator for Domestic Extremism', and with or without a hyphen in Coordinator, and also National Domestic Extremism Coordinator. For convenience we have chosen to use 'National Coordinator for Domestic Extremism' or more generally NCDE.

- ↑ The Welsh Extremism and Counter Terrorism Unit (WECTU), though performing functions similar to the NCDE/NDEU and also connected to ACPO’s Terrorism and Allied Matters Committee, appears to be a distinct unit that answered to Welsh police forces.

- ↑ Personal communication with animal rights and environmental activists corroborated by search of Parliamentary and press publications from the period.

- ↑ David Blakey, A Need to Know, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, January 2003.

- ↑ Clive Walker, Home Office and Policing, Part 3: The Concern for Policing Standards, Department of Law, Leeds University, 1 March 2007, accessed 27 January 2015.

- ↑ New police squad for animal rights extremists, The Times, 27 April 2001.

- ↑ The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI), Corporate Watch, September 2013, viewed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 John Denham, Minister of State Animal Rights Protests (Written Answers, House of Commons), Hansard, 16 May 2002, Vol. 385, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ Animal rights suspects held, BBC News Online, 4 October 2001, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ Anthony France, Animal Activists Arrested, The Evening Standard, 2 October 2001.

- ↑ ACPO, Neil Giles biography, ACPO drugsconference 2009 website, accessed 10 January 2015. Also see Neil Giles profile, ZoomInfo.com'Giles, a former Metropolitan Police officer would go on to become Deputy Director of the Serious Organized Crime Agency with responsibility for HUMINT ('human intelligence'.

- ↑ Caroline Flint, Commons Debates - Written Answers to Questions (7 July 2004), Hansard, Vol. 423, 7 July 2004, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ Animal extremists face crackdown, BBC News Online, 30 July 2004, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ John Steele & Joshua Rosenberg, Police to target ringleaders in campaign against violence, The Telegraph, 29 July 2004, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ Annual Report, National Crime Squad, 16 November 2006, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ No reference of any animal rights focused unit is mentioned in the either 2004-2005 or the 2005-2006 annual reports of the National Crime Agency. Some articles from 2004 refer to specialist units to tackle leading animal rights extremists being set up within the NCS (see: Nigel Morris, New laws 'will end animal extremists' reign of terror', The Independent, 31 July 2014, accessed 10 January 2015.) However, it may be that this is a confusion with either the existing unit, or perhaps that unit is being revitalised with greater powers as part of the same strategy that gives rise to NCDE and the domestic extremism team. One article of 4 July 2004 also notes that at the time of its establishment in March 2004, NETCU was part of the National Crime Squad (see: Tim Webb & Robin Buckley, The rise of investment terrorism: Animal rights extremists are targeting individual company directors and shareholders - with some success, Sunday Tribune, 4 July 2004). That the articles mentioning this mainly occur in July 2004 indicates that the NCDE is being built on the earlier work of the earlier NCS unit. It also suggests that the original home of the NCDE was actually intended to be within the National Crime Squad, but at some stage the decision was for them to be under the direct control of ACPO TAM.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Gordon Mills, The successes and failures of policing animal rights extremism in the UK 2004–2010, International Journal of Police Science & Management, Vol. 15, No.1, 18 February 2013.

- ↑ Rosie Murray-West, Glaxo chief: animal rights cowards are terrorising us, The Telegraph, 28 July 2004, accessed 26 August 2014.

- ↑ Jonathan Watts, Animal rights activists force drug firm to rethink UK role, The Guardian, 15 November 2004, accessed 26 August 2014.

- ↑ Farewell to NETCU: A brief history of how protest movements have been targeted by political policing, Corporate Watch, 19 January 2011.

- ↑ Animal Welfare - Human Rights: protecting people from animal rights extremists, Home Office, July 2004, archived at Statewatch.org, accessed 26 August 2014.

- ↑ Statement of Caroline Flint, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Home Office, to Parliament, Hansard, 7 July 2004: Since becoming the Minister with responsibility for this area, I have had several meetings with representatives from the bioscience industry and other companies. I have met victims of such activity and heard about their experiences at first hand. My colleagues and I are in regular contact across Government, and Lord Sainsbury and I meet regularly. We are not only responding to the general issue, but have responded strongly to the individual targeting of particular companies. We also have regular contact with senior police officers to discuss policing and enforcement at national, regional and local force levels.... The Association of Chief Police Officers recently appointed an assistant chief constable to the new role of national co-ordinator with responsibility for developing regional and national responses to animal rights extremists. As I said, we have also used Home Office funding to create a national extremism tactical co-ordinating unit, which is based in Cambridge. It will provide police forces and others throughout the country with tactical guidance, information and advice.

- ↑ Lech Mintowt-Czyz, Police chief to lead war on animal rights terror, London Evening Standard, 29 July 2004, accessed 26 August 2014.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 24.8 A Review of National Police Units which Provide Intelligence on Criminality Associated with Protest, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, 2 February 2012.

- ↑ It is worth noting that the merging of the domestic extremism / public order units in 2004-2006 took place at the same time as a major reorganisation of counter-terrorism policing in the UK in the wake of the July 7 bombings of 2005 and a significant increase in the number of counter-terrorism investigations since 2001. This included the merging of the Metropolitan Police's Special Branch and Anti-Terrorism Branch into the combined Counter-Terrorism Command, and the setting up of regional Counter-Terrorism Units and Counter Terrorism Intelligence Units as part of a national Police counter terrorism network. See for example: DS Philip Williams, Witness Statement, Leveson Inquiry, 29 September 2011, p.9.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Adapting to Protest - Nurturing the British Model of Policing, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, November 2009.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 National Co-ordinator Domestic Extremism, Frequently Asked Questions, Association of Chief Police Officers, ca. 2010-2011, archived by Undercover Research Group.

- ↑ See for example postholder, office of NCDE, Response to a FOIA request of David Cinzano, 25 November 2014, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ Freedom of Information Act Request 000185/13: ACPO Funding, Association of Chief Police Officers, 2013. Various other FOIA requests and official reports indicate that NPOIU was founded with Home Office funding, and likewise, Cambridgeshire police was paid by the Home Office for NETCU – see for example, Cambridge Police Authority Statement of Accounts 2006/07, when it received £136,000.

- ↑ Written Answers to Questions: Association of Chief Police Officers, Response of Government Minister Damien Green to a written question by Tim Loughton, Hansard, 9 December 2013, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ Nick Collins, What is the National Public Order Intelligence Unit?, The Telegraph, 10 January 2011, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ [ http://static.london.gov.uk/mqt/public/question.do?id=35775 Mayor answers to London: Transfer of Covert Police Operations, a written response to question by Lee Duvall], The London Assembly, 1 April 2011, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 National Policing Requirement, Association of Chief Police Officers, 2012, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 NCDE National Coordinator Domestic Extremism, Frequently Asked Questions, Association of Chief Police Officers, 2011. The is now dead, but archived by Undercover Research Group.

- ↑ Briefing Note on the Police Superintendents’ Association of England & Wales (PSAEW) for members of the Police and National Crime Agency Pay Review and Remuneration Body, Police Superintendents' Association of England and Wales, 1 July 2014, accessed 10 January 2014.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 ACPO welcomes 'economic damage' amendment to the Serious Organised Crime and Police Bill, ACPO press release, 31 January 2005. Archived at archive.today, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ While sources refer to the National Crime Squad as coming under the NCDE's remit, it is more likely this is a confusion with its unnamed unit focusing on animal activism, rather than the NCS per se; this confusion is compounded by later sources discussing the domestic extremism units often ignore the role of the NCS unit (see above).

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Letter Bombs - Police Issue Warning, ACPO press release 7 February 2007, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ 10 Victoria Street], ‘’GovernmentBuildings.co.uk’’, accessed 30 August 2014.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Karen Fox, 'Current postholder, office of NCDE' - response to FOIA request of David Cinzano, Metropolitan Police Service, 22 December 2014, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Undercover Policing Interim Report, House of Commons Home Affairs Committee, Thirteenth Report of Session 2012–13, 26 February 2013.

- ↑ POLICE: Top job for county cop in war on extremists, Peterborough Evening Telegraph, 5 April 2004.

- ↑ Response to FOIA Request of Mr. Graham, Metropolitan Police, 20 March 2013, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ As yet unconfirmed, it appears that the Animal Rights National Index was for a while part of the National Crime Intelligence Unit, a sister unit to the National Crime Squad.

- ↑ Prime organizers were the Metropolitan Police Special Branch commanders Barry Moss who was expected to lead the unit (see Jason Bennetto, Police unit to target green protesters, The Independent, 7 November 1998, accessed 10 January 2015) and Roger Pearce, as well as then Assistant Commissioner for Specialist Operations, David Veness (Unpublished minutes of meetings of the ACPO Terrorism and Allied Matters committee from 1998-2000).

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Mick Creedon, Operation Herne: Report 1 - Use of Covert Identities, Derbyshire Constabulary, July 2013, page 79.

- ↑ Minutes of ACPO TAM meetings relating to the establishment of the NPOIU, 1998-2000, unpublished.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 48.5 A review of progress made against the recommendations in HMIC’s 2012 report on the national police units which provide intelligence on criminality associated with protest, Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary, June 2013.

- ↑ Police extremist unit helps climate change e-mail probe, ‘’BBC News Online, 11 January 2010, accessed 30 August 2014.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Police on 'tightrope' at protests, Press Association, 23 November 2010, accessed from archive.today 19 June 2014. Note, date on page refers to the date it was archived; actual date of article derived in this case from the page's URL

- ↑ National Domestic Extremism Unit, ACPO site. Accessed 2 October 2013.

- ↑ Letter from ACPO in response to a FOIA request, Association of Chief Police Officers , 2 February 2012, accessed 30 August 2014.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Jason Lewis, Did police cutbacks allow extremists to hijack student demonstrations?, The Telegraph, 14 November 2011, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 About NDEDIU, Association of Chief Police Officers, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ The Rules of Engagement: A review of the August 2011 disorders, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, 20 December 2011, para. 2.35.

- ↑ Police - Response to FOIA request of Ashley Davis of 5 November 2013 to the Metropolitan Police Service, WhatDoTheyKnow.com, 5 December 2013, accessed 30 August 2014.

- ↑ Judgment in case of Catt vs Association of Chief Police Offices and ors., Court of Appeal (Civil Division), (2013) EWCA Civ 192, 14 March 2013.

- ↑ Examination of Witnesses (Question Numbers 199-240) Rt Hon Nick Herbert MP, Home Affairs Committee, 18 January 2011, accessed 18 June 2014.

- ↑ James Slack, Police chiefs body loses power to run undercover units in wake of eco-warrior spy scandal, Daily Mail, 18 January 2011, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Alan Travis, Paul Lewis & Martin Wainwright, Clean-up of covert policing ordered after Mark Kennedy revelations, The Guardian, 18 January 2011, accessed 26 August 2014.

- ↑ Rob Evans, [1], The Guardian, 1 March 2012, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ Public Order Standard Operating Procedure, ‘’Police Scotland’’, 11 September 2013, accessed 30 August 2014.

- ↑ Response to an FOIA request made by Jason Sands (No. 2011020001329), Metropolitan Police Service, 2 March 2011, accessed 10 January 2014.

- ↑ A letter of Mark Knight of the Metropolitan Police's Director of Information of 28 March 2011, cited at Judicial Review Letter before claim response required by the close of business on 20 November 2014, Bhatt Murphy Solicitors, 6 November 2014, accessed 10 January 2014, para 5.6(g), p. 15. Some sources appear to mistakenly cite date of transfer as January 2012.

- ↑ Domestic Extremism, MI5.gov.uk, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Protecting the public: Police coordination in the new landscape, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, 14 August 2012, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Freedom of Information Request Reference Number: 000150/12 - TAM Staff Structure, Association of Chief Police Officers, undated, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Personnel Information Systems - Police & Police Staff Strength as at March 2012, West Yorkshire Police and Crime Commissioner, undated, accessed 31 August 2014.