National Domestic Extremism Unit

|

This article is part of the Counter-Terrorism Portal project of SpinWatch. |

This article is part of the Undercover Research Portal at PowerBase - investigating corporate and police spying on activists.

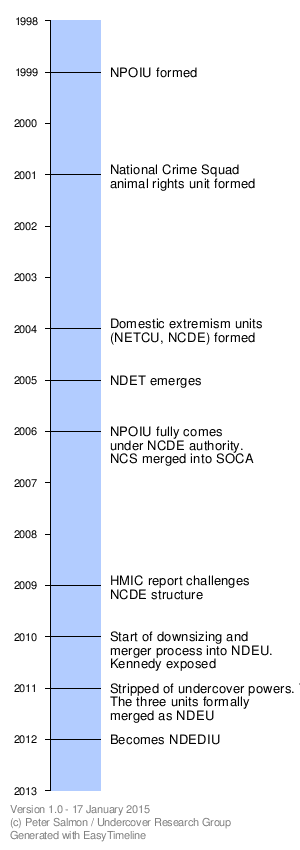

The National Domestic Extremism Unit refers to specialist police organisation that began life as the National Coordinator for Domestic Extremism (NCDE),[1] and was subsequently renamed the National Domestic Extremism Unit (NDEU) and more recently the National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit (NDEDIU). For much of its history it was controlled by the Association of Chief Police Officers' Terrorism and Allied Matters Committee, before being transferred to the the Metropolitan Police Service's Counter Terrorism Command in the wake of the Mark Kennedy undercover scandal.

During its time under the control of ACPO, the NDEU consisted of a group of police units, several of which have gained national attention for their role in the policing of protests and deployment of undercover police into political and activist movements. These units were the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU), National Extremism Tactical Coordination Unit (NETCU), National Domestic Extremism Team (NDET).[2] Many began as separate units, or created out of the merger of smaller units around the UK. It was a sub-unit of the NPOIU, the Confidential Intelligence Unit, which ran a number of infiltrators that targeted protest movements.

The unit is notable for its targeting of the letter bomber Miles Cooper and the animal rights campaign Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty. However, it has run into controversy over the definition of domestic extremism, its monitoring of peaceful protestors and recording of details on its database, its links with industry and the activities of undercover officers it used to target various protest movements, most notably Mark Kennedy.

This page gives a general overview of the units dealing with domestic extremism.

For more detail, see the following sub-pages:

Contents

Creation of the unit

- For a detailed account of the history and organisation of the units see National Domestic Extremism Unit: organisational history

Much of the impetus for the domestic extremism units came from the resurgence of militant animal right campaigning in the late 1990s and 2000s, particularly targeting the animal testing laboratory Huntingdon Life Sciences in Cambridgeshire and a new biotech laboratory in Oxford. Up to this point, activists were generally referred to as 'Animal Rights Extremists' by the police and press and in Parliamentary debates, with militant environmental campaigning being referred to as 'eco-terrorism' rather than extremism.[3]

A number of police units had been set up previously including

- National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU) - established in 1999 to target animal rights and environmental protestors.

- A specialist unit within the National Crime Squad.

In 2004, following high profile activity by the animal rights movement the UK government reacted by establishing the National Coordinator for Domestic Extremism (NCDE) under the aegis of the Association of Chief Police Officers' Terrorism and Allied Matters Committee (ACPO TAM). In the same year, the National Extremism Tactical Coordination Unit (NETCU) was created by Cambridgeshire Police, in conjunction with the National Crime Squad and funded by the Home Office.

From 2004 and 2006, there was a growth and consolidation of the role of National Coordinator of Domestic Extremism. The National Domestic Extremism Team was created to give the NCDE operational ability, while NETCU and NPOIU were gradually integrated into it. NETCU would be a source of practical knowledge and policing advice, including working with the private sector, while NPOIU would provide the intelligence. The third part would be the National Domestic Extremism Team, which was made up of officers seconded from other forces and carry out criminal investigations into animal rights and other protestors. This reorganisation was taking place when the 2005 July 7th bombings in London occurred, prompting a reorganising of counter-terrorism policing in the UK, particularly of those branches of the police which would have had oversight of the domestic extremism.[4]

With the merging in of the NPOIU, the remit was able to extend beyond domestic extremism to public order which helped facilitate the extension of its original mission from focusing on animal rights to protest as a whole,[5] based on the relationship between protest groups being active through marches and other demonstrations.

By the end of 2006, the roles of NPOIU, NETCU and NDET under the NCDE was intelligence, prevention and enforcement respectively, while ‘their core role is provide support and advice to police forces that remain responsible for intelligence, prevention and enforcement functions within their respective local force areas.’ [6]

While the NDCE and its units were funded primarily by the Home Office, it was independent of that department, and also worked with other departments such as the Department for Business, Innovation and Trade.[7] However, understanding of the picture of funding is hampered by refusal by ACPO and the Home Office to answer questions on the funding.[8]. The unit's office address was given as 10 Victoria Street, London, SW1H ONN, which is the ACPO headquarters and which building is home to a number of other police organisations and Home Office units.[9]

Role of the National Coordinator Domestic Extremism

The head of the NCDE, the National Coordinator Domestic Extremism (NCDE -sometimes also given as NDEC) answered directly to ACPO's Terrorism and Allied Matters Committee.[10] According to an interview on 25 July 2009, he had no ‘executive authority or control’ over police forces, and his only oversight was by way of reporting to the TAM committee. [6] The main purpose of his role was ‘to coordinate the police response to single-issue, domestic extremism’.[11] In 2012 it was described as providing ‘strategic support and direction to police forces dealing with domestic extremism investigations’.[5]

In December 2014, the Metropolitan Police confirmed that the role of NCDE was still existent and the title given to the head of the NDEDIU.[12]

Member Units (2004-2011)

NETCU

NETCU was established in March 2004 by the Chief Constable of Cambridgeshire in response the animal rights campaign against Huntingdon Life Sciences[13] with Home Office funding and based out of Huntingdon. Initially it was part of the National Crime Squad.[14] Its responsibility was to act as an interface between police and those companies / institutions who were the subject of campaigns and protests, as well as supporting local police forces by producing guidance. It later extended its interest to other protests, particularly environmental. A similar unit, WETCU, was also established in Wales.

Much of the work of NCDE and NDEU was often attributed to NETCU by protestors; as the more public face of the various units, it attracted most attention, including monitoring by blogs such as NETCU-Watch.

- See also NETCU

NPIOU

The NPIOU was formed in 1999 as part of a national strategy within ACPO around public order issues, and funded by the Home Office, in particular:[15]

- it was established to support police forces in managing the intelligence around the threat to communities from public disorder connected to domestic extremism and single issue campaigning.

Its basis was the Animal Rights National Index,[16] and rooted within Special Branch,[17] through which it drew upon officers from the Special Demonstration Squad.[18] Pre-existing intelligence gathering units - the Northern Intelligence Unit and the Southern Intelligence Unit that had monitored travellers and protestors during the 1990s - were incorporated into it as satellite organisations. [19] Later its work was described as: [20]

- to reduce criminality and disorder from domestic extremism and to support forces in the way they dealt with strategic public order issues, including by gathering intelligence through the deployment of undercover officers.

It was charged with maintaining a database on protestors and activists, but early on it created a sub-unit, the Confidential Intelligence Unit (CIU) which ran infiltrators. It is known that undercover officer Mark Kennedy was deployed by CIU in 2003, but he is believed to have replaced an earlier officer, Rod Richardson who was active from 1999 to 2003.

- See also NPOIU

NDET

NDET was a unit of detectives set up in 2005[5] by ACPO to provide assistance - practical and intelligence - to police forces facing protests from 'domestic extremists', and to look at all crimes 'linked to single-issue type causes and campaigns'. In particular, it was 'responsible for co-ordinating police operations and investigations against domestic campaigns and extremists, as well as identifying possible linked crimes across the country.[7] The unit came to public attention when it led the investigation into the letter bomber Miles Cooper[11] and was asked to assist the investigation into the hacking of the Climate Research Unit at University of East Anglia.[21] It also oversaw Operation Achillies under DCI Andy Robbins which investigated Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (see below).

2011: Reorganisation and downsizing

In 2009 and 2010 a number of reports highlighted issues of weak governance and oversight within the units.[13] At the time the NDEU had a staff of about 100 and a budget of 8.1million.[22] It was decided to move it from ACPO's control[5] and to merge the role of National Co-ordinator for Domestic Extremism and the three units under him into one unit- the National Domestic Extremism Unit (NDEU).[20][23][24] This was finalised in January 2011, at a meeting of ACPO's top decision body, the Chief Constables Council.[18] DCS Adrian Tudway was appointed as the new NCDE - replacing Setchell who had been told to resign that month.[25]

For the most part, the activities of the combined unit were to remain the same,[26] including the handling 'intelligence related threats across force, national and international boundaries’ - inherited from the NPOIU [27]

The merger of January 2011 involved a downsizing of the units, the loss of senior officers and budget cuts put in place.[25] The unit itself was given lesser status with Setchell's two successors as NCDE, Tudway and Greany (see below), not given the rank with the ‘seniority of a chief officer’, [5] but holding the lesser with rank of Detective Chief Superintendent.[28][22] The newly combined National Domestic Extremism Unit formally transferred to the control of the Metropolitan Police's Counter Terrorism Command on 1 June 2011.[29]

At the same time downsizing and merging was taking place, the scandal around Mark Kennedy, an NPOIU undercover officer, was breaking. This led the Minister for Police, Nick Herbert to declare of the units that ‘operationally something has gone very wrong’, [30] and subsequently stripped the NDEU of its operational powers, in particular its ability to infiltrate protest movements with undercover officers. [31]

Transfer of control to the Metropolitan Police

Following the transfer, the NDEU initially retained the intelligence collection, investigation support and awareness raising functions of its precursor units: [5] One of its subunits was the Strategic Threat Assessment, which was one of two police organisations identifying threats to public order. Listed as events which provided practical learning experiences for the policing of large scale disorder were the G20 protests, English Defence League demonstrations and the August 2011 riots, in all of which NDEU has played a role. [32]

Oversight of the NDEU was placed under Senior National Coordinator for Counter Terrorism.[5] The Head of NDEU, then reported through the head of the MPS’s Counter Terrorism Command to the Chair of the ACPO Terrorism and Allied Matters Business Area; while the unit continued to be funded by ACPO and the Home Office. [33] The ACPO Terrorism and Allied Committee continued to provide ‘the development of police service policy and strategy in respect of relevant counter terrorism, domestic extremism and other policing themes.’ [34]

Though now housed with the Metropolitan Police, it retained its national function, and had officers seconded from other forces.[35]

Renamed to NDEDIU

In 1 May 2013 the NDEU was formally renamed the National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit (NDEDIU).[26] It retained control of its database / intelligence gathering function (see below) and continued to lead investigations, most notably that leading to the imprisonment of SHAC activist Debbie Vincent in 2014.

Subsequently, the NDEDIU was organized into two units (following acceptance of the NDEU Business Development Plan for the Establishment of a National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit put forward in October 2012 and agreed by ACPO’s Chief Constables Council in May 2013): [20]

- a) Protest and Disorder Intelligence Unit. This unit collates and provides strategic analysis relating to protest and disorder across the UK; and

- b) Domestic Extremism Intelligence Unit. This unit provides strategic analysis of domestic extremism intelligence within the UK and overseas.

The unit now has a single page at website of the National Police Chiefs' Council, which replaced the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO). It describes its work as:

- The NDEU [sic - this is the old name] supports all police forces to help reduce the criminal threat from domestic extremism across the UK. It works to promote a single and co-ordinated police response by providing tactical advice to the police service alongside information and guidance to industry and government.

- One of the key responsibilities of the NDEDIU is to provide intelligence on domestic extremism and strategic public order issues in the UK. Police will always engage to facilitate peaceful protest, prevent disorder and minimise disruption to local communities. Where individuals cross over into criminality and violence, the police will act swiftly and decisively to uphold the law.[36]

Definition of Domestic Extremism

- For more detail on the definition, see: Domestic Extremism

There is no legal definition of domestic extremism. The term emerged in the early 2000s as a way of characterising militant animal rights campaigns. From there it expanded to cover those 'that carry out criminal direct action in furtherance of a campaign. These people and activities usually seek to prevent something from happening or to change legislation or domestic policy, but attempt to do so outside of the normal democratic process."[37]

In 2011, the ACPO website for the NCDE stated the following:[38]

- Who is considered a domestic extremist?

Single issue protest campaigns are regularly facilitated by police and local authorities who each have a duty to uphold the rights of individuals and groups to protest in public.

However, in recent years, a small number of groups and individuals have pursued a determined course of criminal activity designed to disrupt the public peace and lawful business, and at worst, repeatedly victimise selected individuals.

This activity has ranged from blackmail and serious intimidation in the name of animal rights; bombing campaigns by violent and racist individuals associated with far right wing groups; violent disorder from left wing or anarchist individuals, to large scale criminal damage against scientific GM crops studies and mass aggravated trespass or unlawful obstruction of lawful businesses associated with the national infrastructure of our country, such as power stations and airports by those who’s stated aim is to stop any business perceived to harm the environment.

In 2014 a revised working definition was provided by the Metropolitan Police as:[39]

- Domestic Extremism relates to the activity of groups or individuals who commit or plan serious criminal activity motivated by a political or ideological viewpoint.

Targeting of lawful protest

The broad definition of domestic extremism caused controversy when it was realized it was being used by the police to monitor all protest groups regardless of their intentions towards what might be deemed criminal behaviour. It was also noted that the phrase carried no legal definition and had a very wide interpretation. This led to a campaign by various groups around the criminalization of protest and in relation to the retaining of data on the NPOIU / NDEU database.

The 2011 ACPO / NCDE website repeated maintained that it did not target lawful protestors:[38]

- The National Domestic Extremism Unit does not usually focus those who choose to protest peacefully and lawfully. The unit is mainly concerned with those who commit criminal offences in furtherance of their campaign.

However, during a 2014 trial it was revealed that two long standing NDEU officers, Ian Caswell (retired) and Christopher Cowley, had carried out frequent surveillance of peaceful demonstrations, including photographing individuals, logging when the entered or left private events / gatherings and recording number plates.[40][41] This backed up long standing complaints by protest groups and others that the criminalisation of otherwise lawful protest was effectively taking place.[42]

Work of the domestic extremism units

- See main page: National Domestic Extremism Unit: activities

A 2009 the work carried out by the domestic extremism units was for stated as 'reducing or removing the threat, criminality and public disorder that arises from domestic extremism in England and Wales specifically, and the UK generally'; it went on to categorise domestic extremism as:[43]

- Animal Rights Extremism

- Environment Extremism

- Extreme Right Wing

- Extreme Left Wing

- Emerging Threats

Though animal rights provided the motivation for creating the domestic extremism units, from early on its work encompassed other movements such as anti-capitalism, eco-defence and peace movements,[44] while the careers of "Lynn Watson" and Mark Kennedy show a clear interest in environmental campaigns such as Climate Camp, and also anti-fascism.

In 2013, Assistant Commissioner for Specialist Operations, Cressida Dick said the 'National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit (NDEDIU) sets the national strategic direction for understanding extremist threats to the UK. It has a wide range of international partners which it works with, particularly law enforcement and security agencies in Europe.'[45]

NDEU / NPOIU database and intelligence gathering

- For more detail see: National Domestic Extremism Database

One the functions of the NPOIU was the maintaining a database of individuals related to protest, something it had inherited from the Animal Rights National Index. Over time this database, known as the National Domestic Extremism Database grew to include images and details of up to 9000 protestors.[46] Officers from the domestic extremism units were regularly seen at protests and other political gatherings noting details and taking photographs,[47] As well as its own officers, it gathers intelligence from other forces and specialist units[20][48], and uses specialist software to scan social media.[49]

It became a subject of controversy when campaigners claimed that it was helping to criminalize protest.[50] Further controversy was added when it became known that ‘spotter cards’ based on it were being issued to local police at major events, [51] and later when it emerged that much of the detail on it related to lawful activity.[52] Following two court cases which found police retention of protestor surveillance breached human rghts,[29][53] and two inspections by HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, it was ordered to be cleaned up and better processes put in place.[5] However, it remains in place being one of the key functions of the domestic extremism units that has survived the reorganization and transfer to the Metropolitan Police, and the fallout from the Mark Kennedy scandal. [20]

It has been the subject of a number of legal challenges over the validity and retention of data on it (see National Domestic Extremism Database for further detail).

Targeting Animal Rights

A central aspect of the NCDE / NDEU work was the targeting of animal rights campaigns, in particular Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty and SPEAK. In this it worked in collaboration with five other forces as part of an extensive set of operations.[54]

In 2007 it saw the arrest of 32 people and the subsequent conviction in 2008 and 2009 of a number of leading SHAC activists. At its height, it was the largest police operation of its time in the UK,[55] involving 700 police officers, including from Holland and Belgium, and involved the bugging of homes and cars.[56]

As part of these operations, it is known the NCDE / NDEU collaborated with other parts of the justice system, including working with the Crown Prosecution Service.[54] NETCU also played a leading role in assisting civil injunctions to be taken out.[57]

Monitoring the Far Right

On 27 April 2011, the then National Coordinator for Domestic Extremism, DCS Adrian Tudway caused anger in the Muslim community when he wrote that he did not consider the anti-Islamist English Defence League as ‘not extreme right-wing as a group’ and that a ‘line of dialogue’ should be opened with them. [58]

However, from May 2011 the NDEU worked with local police forces to obtain anti-social behaviour orders (ASBOs) against EDL members[59]

Home Office minister James Brokenshire said in 2013 that the NDEU was involved in collating and analyzing intelligence on the Far Right.[60] This included analysing footage of EDL protests to see if Norwegian mass murderer Anders Behring Breivik had taken part in their demonstrations.[61]

August 2011: the London riots

During the August 2011 riots, the NDEU provided ‘support and daily tension briefings’ for the President of ACPO who was attending COBR meetings with the Government. This followed the Police National Information and Coordination Centre being overwhelmed by the demands being placed on it due to the scale of the disorder.

Relationship with private security

A number of officers involved in the domestic extremism units have gone on to work in the private security and intelligence world.[62] The 2012 HMIC report into the units stated:[5]

- A close relationship was built up over a number of years between the NDEU and those industries which found themselves the target of protests, to raise awareness of threats and risk so that damage and injury could be prevented. A number of police officers have retired from NDEU's precursor units and continued their careers in the security industry, using their skills and experience for commercial purposes.

In particular, NETCU is known for close links with with the vivisection and pharmaceutical industries, and it has been revealed that it met with blacklisting firm The Consultancy Association in November 2008.[63]

The most recent description of the work of the unit now called the NDEDIU at its website (as quoted above) includes giving 'information and guidance to industry and government'.

Other Undercover Research sources

- See National Domestic Extremism Unit: officers for details of holders of the office National Coordinator for Domestic Extremism and other senior police officers involved in the leadership of the domestic extremism units.

- National Public Order Intelligence Unit

- National Extremism Tactical Coordination Unit

- Association of Chief Police Officers (Terrorism and Allied Matters)

- Special Demonstration Squad

- Mark Kennedy

External Resources

- Britain's Secretive Police Force – Politicising the Policing of Public Expression in an Era of Economic Change (Paper Q2), electrohippies, April 2009.

Notes

- ↑ There is no consistent title for this position, with various official documents using 'National Coordinator Domestic Extremism’, ‘National Coordinator - Domestic Extremism’, ‘National Coordinator of Domestic Extremism’, 'National Coordinator, Domestic Extremism' or 'National Coordinator for Domestic Extremism', and with or without a hyphen in Coordinator, and also National Domestic Extremism Coordinator. For convenience we have chosen to use 'National Coordinator for Domestic Extremism' or more generally NCDE.

- ↑ The Welsh Extremism and Counter Terrorism Unit (WECTU), though performing functions similar to the NCDE/NDEU and also connected to ACPO’s Terrorism and Allied Matters Committee, appears to be a distinct unit that answered to Welsh police forces.

- ↑ Personal communication with animal rights and environmental activists corroborated by search of Parliamentary and press publications from the period.

- ↑ This included the merging of the Metropolitan Police's Special Branch and Anti-Terrorism Branch into the combined Counter Terrorism Command, and the setting up of regional Counter Terrorism Units and Counter Terrorism Intelligence Units as part of a national Police counter terrorism network. See for example: DS Philip Williams, Witness Statement, Leveson Inquiry, 29 September 2011, p.9.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary, A Review of National Police Units which Provide Intelligence on Criminality Associated with Protest, 2 February 2012.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Adapting to Protest - Nurturing the British Model of Policing, November 2009.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Association of Chief Police Officers, National Co-ordinator Domestic Extremism, Frequently Asked Questions, circa 2010-2011, archived by Undercover Research Group.

- ↑ See for example Metropolitan Police Service, Current postholder, office of NCDE, Response to a FOIA request of David Cinzano, WhatDoTheyKnow.com, 22 December 2014, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ 10 Victoria Street, GovernmentBuildings.co.uk, accessed 30 August 2014; data sourced from data.gov.uk under the Open Government Licence.

- ↑ Association of Chief Police Officers, "ACPO welcomes 'economic damage' amendment to the Serious Organised Crime and Police Bill", press release, 31 January 2005. Originally at ACPO website, archived at archive.today on 1 Mar 2006, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Association of Chief Police Officers, Letter Bombs - Police Issue Warning, press release, 7 February 2007, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ Metropolitan Police Service, 'Current postholder, office of NCDE' - Response by Metropolitan Police Service to FOIA request of David Cinzano, 22 December 2014, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Thirteenth Report of Session 2012–13: Undercover Policing Interim Report, Home Affairs Select Committee, 26 February 2013.

- ↑ POLICE: Top job for county cop in war on extremists, Peterborough Evening Telegraph, 5 April 2004.

- ↑ Response to FOIA Request of Mr. Graham, Metropolitan Police, 20 March 2013, accessed 10 January 2015.

- ↑ As yet unconfirmed, it appears that the Animal Rights National Index was for a while part of the National Crime Intelligence Unit, a sister unit to the National Crime Squad.

- ↑ Prime organizers were the Metropolitan Police Special Branch commanders Barry Moss who was expected to lead the unit (see Jason Bennetto, Police unit to target green protesters, The Independent, 7 November 1998, accessed 10 January 2015) and Roger Pearce, as well as then Assistant Commissioner for Specialist Operations, David Veness (Minutes of ACPO's Terrorism and Allied Matters committee meetings relating to the establishment of the NPOIU, 1998-2000, hard copy released through Freedom of Information Act request).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Mick Creedon, Operation Herne: Report 1 - Use of Covert Identities, Derbyshire Constabulary, July 2013, page 79.

- ↑ Minutes of ACPO's Terrorism and Allied Matters committee meetings relating to the establishment of the NPOIU, 1998-2000, hard copy released through a Freedom of Information Act request.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, A review of progress made against the recommendations in HMIC’s 2012 report on the national police units which provide intelligence on criminality associated with protest, June 2013.

- ↑ Police extremist unit helps climate change e-mail probe, BBC News Online, 11 January 2010, accessed 30 August 2014.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Police on 'tightrope' at protests, Press Association, 23 November 2010. Orginally at Press Association website, archived at archive.today on 11 Sept 2012, accessed 19 June 2014. Note: date on page refers to the date it was archived; actual date of article derived in this case from the page's URL.

- ↑ National Domestic Extremism Unit, ACPO site. Accessed 2 October 2013.

- ↑ Association of Chief Police Officers, Letter from ACPO in response to a FOIA request, 2 February 2012, accessed 30 August 2014.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Jason Lewis, Did police cutbacks allow extremists to hijack student demonstrations?, The Telegraph, 14 November 2011, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Association of Chief Police Officers, About NDEDIU, undated, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary, The Rules of Engagement: A review of the August 2011 disorders, 20 December 2011, para. 2.35.

- ↑ Metropolitan Police Service, Police - Response to FOIA request of Ashley Davis of 5 November 2013, WhatDoTheyKnow.com, 5 December 2013, accessed 30 August 2014.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Judgment in case of Catt vs Association of Chief Police Offices and ors., Court of Appeal (Civil Division), (2013) EWCA Civ 192, 14 March 2013.

- ↑ Examination of Witnesses (Question Numbers 199-240) Rt Hon Nick Herbert MP, Home Affairs Select Committee, 18 January 2011, accessed 18 June 2014.

- ↑ James Slack, Police chiefs body loses power to run undercover units in wake of eco-warrior spy scandal, Daily Mail, 18 January 2011, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ Association of Chief Police Officers, National Policing Requirement, 2012, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary, Protecting the public: Police coordination in the new landscape, 14 August 2012, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Association of Chief Police Officers, Freedom of Information Request Reference Number: 000150/12 - TAM Staff Structure, undated, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ West Yorkshire Police and Crime Commissioner, Personnel Information Systems - Police & Police Staff Strength as at March 2012, undated, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ National Police Chiefs' Council, National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit, About NDEDIU, no date (accessed February 2016)

- ↑ How police rebranded lawful protest as 'domestic extremism', The Guardian, 25 October 2009. Accessed 25 December 2013.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Association of Chief Police Officers, NCDE National Coordinator Domestic Extremism, Frequently Asked Questions, 2011. This link is now dead, but has been archived by Undercover Research Group.

- ↑ Metropolitan Police Service, Response by Metropolitan Police Service to a FOIA request made by Kevin Blowe (No: 2014030001361), WhatDoTheyKnow.com, 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Blackmail3 Solidarity, Blackmail3 Court Case Update, Indymedia UK, 16 March 2014, accessed 26 August 2014.

- ↑ It should be noted that protestors often confused the various police units, often wrongly assuming that all police officers monitoring protests, including Forward Intelligence Teams were part of NETCU, which because of its more public role in injunctions had a much higher profile than the other units. See for example, the NETCU WATCH! website, and State Crackdown on Anti-Corporate Dissent, Corporate Watch, 2009. It was not until 2011 that a wider understanding of the make up and history of the domestic extremism units became better known - see Farewell to NETCU: A brief history of how protest movements have been targeted by political policing, Corporate Watch, 19 January 2011.

- ↑ See for example, the FITWatch campaign and State Crackdown on Anti-Corporate Dissent, Corporate Watch, 2009.

- ↑ National Co-ordinator Domestic Extremism, Head of Confidential Intelligence Unit (Job Description), 2009, acquired and published by Plane Stupid, accessed 10 January 2015. This description has been echoed in other documents - see under Domestic Extremism for further details.

- ↑ For example, see Association of Chief Police Officers, ACPO Manual of Guidance on DEALING WITH THE REMOVAL OF PROTESTORS FASLANE 365 2006 - 2007, 2007.

- ↑ Update by Assistant Commissioner Cressida Dick on the murder of Drummer Lee Rigby, Home Affairs Select Committee, June 2013, accessed 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Paul Lewis, Rob Evans and Vikram Dodd, National police unit monitors 9,000 'domestic extremists', The Guardian, 26 June 2013, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ The monitoring of activists is regularly chronicled on sites such as FITWatch.org.uk and Indymedia.org.uk.

- ↑ Metropolitan Police Service, Police Liaison "Gateway" Team, document released following FOIA request of Kevin Blowe and published by Netpol in June 2014.

- ↑ Paul Wright, Meet Prism's little brother: Socmint, Wired, 26 June 2013, accessed 26 August 2014.

- ↑ Paul Mobbs / The Free Range Network, Paper Q2: Britain’s Secretive Police Force, electrohippies project, April 2009, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Spotter cards: What they look like and how they work, The Guardian, 25 October 2009, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Kevin Blowe, Secret Diary of an Olympic Domestic Extremist, Random Blowe (blog), 5 February 2014, accessed 24 June 2014.

- ↑ Judgment in Wood v Commissioner of the Metropolis, Court of Appeal (Civil Division), 2009 EWCA Civ 414, 21 May 2009.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Gordon Mills, The successes and failures of policing animal rights extremism in the UK 2004–2010, International Journal of Police Science & Management, Vol. 15, No.1, 18 February 2013.

- ↑ Police quiz animal activists, The Express, 1 May 2007, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Robin Turner, Jailed animal activist speaks from behind bars, Wales Online, 25 January 2009, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Personal Communication from Dr. Max Gastone.

- ↑ Vikram Dodd & Matthew Taylor, Muslims criticise Scotland Yard for telling them to engage with EDL, The Guardian, 2 September 2011, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ For further details see under National Domestic Extremism Unit: activities.

- ↑ Transcript of speech of James Brokenshire, International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, 15 March 2013, accessed 29 June 2014.

- ↑ Jonathan Calvert, Anders Behring Breivik had surgery to look 'Aryan', The Australian, 31 July 2011, accessed 22 June 2014.

- ↑ Undercover Research Group, Re-visiting NETCU - Police Collaboration with Industry, Corporate Watch, 6 August 2014, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Chloe Stothart, Police question evidence of blacklisting collusion, Construction News, 14 October 2013, accessed 10 January 2014.