Islamist-Islamism

Islamism (and the associated Islamist) are terms that are used very widely in contemporary discourse. This page will chronicle the various uses of the term, the historical pattern of its usage, consider alternatives and the arguments for and against using particular terms. It will examine whether particular definitions or general use of the term is analytical and descriptive or whether in some, or all, circumstances it is a prejudicial term, including whether it might be seen as Islamophobic.

History of usage

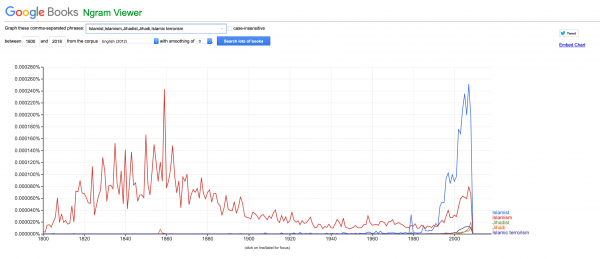

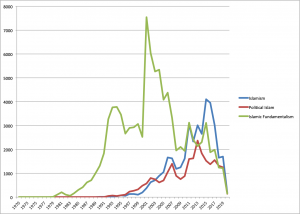

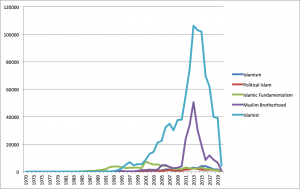

The term Islamism historically referred to either adherents of Islam (ie Muslims) or to students of Islam eg Orientalists. It was a term used widely in English from as early as 1800, peaking in books published in English around 1860 and declining to residual use by the turn of the century. Its occurrence only picked up, as the Google Ngram image shows, but this time in a mostly new sense, at the end of the 1980s.

What caused the reinvention and reinterpretation of the term Islamism (and around the same time, the coining of a new term to go with it - Islamist)?

Bernard Lewis

One of the earliest articles of note was by Bernard Lewis a 'renowned British-American historian of Islam and the Middle East. A former British intelligence officer, Foreign Office staffer, and Princeton University professor.'[1]

In January 1976 he published a piece in the Zionist/Neoconservative magazine Commentary, which at that stage was still published by the American Jewish Committee. Titled 'The return of Islam' it raised the spectre of 'new forms of pan-Islamic activity.'[2] It sets out to insist that the problem with Islam is that it is a religion. Thus he chides the West for not understanding that Muslims are not like us. 'We are prepared' he states 'to allow religiously defined conflicts to accredited eccentrics like the Northern Irish, but to admit that an entire civilization can have religion as its primary loyalty is too much.'[2]

The phrase 'pan-Islamism' was used nine times in the piece in an account that proposed that the problem with Muslims in politics is that they take their religion too seriously. Lewis traces the 'Islamic' connections and rationale of a whole host of organisation's including secular nationalist groups like Fatah:

- The imagery and symbolism of the Fatah is strikingly Islamic. Yasir Arafat’s nom de guerre, Abu ‘Ammar, the father of ‘Ammar, is an allusion to the historic figure of ‘Ammar ibn Yasir, the son of Yasir, a companion of the Prophet and a valiant fighter in all his battles. The name Fatah is a technical term meaning a conquest for Islam gained in the Holy War. It is in this sense that Sultan Mehmet II, who conquered Constantinople for Islam, is known as Fatih, the Conqueror. The same imagery, incidentally, is carried over into the nomenclature of the Palestine Liberation Army, the brigades of which are named after the great victories won by Muslim arms in the Battles of Qadisiyya, Hattin, and Ayn Jalut. To name military units after victorious battles is by no means unusual. What is remarkable here is that all three battles were won in holy wars for Islam against non-Muslims—Qadisiyya against the Zoroastrian Persians, Hattin against the Crusaders, Ayn Jalut against the Mongols. In the second and third of these, the victorious armies were not even Arab; but they were Muslim, and that is obviously what counts. It is hardly surprising that the military communiqués of the Fatah begin with the Muslim invocation, “In the name of God, the Merciful and the Compassionate.”[2]

Bernard Lewis 'was' writes Hamid Dabashi, 'not a regular rogue. He was instrumental in causing enormous suffering and much bloodshed in this world. He was a notorious Islamophobe who spent a long life studying Islam in order to demonise Muslims and mobilise the mighty military of what he called "the West" against them.'[3]

Enter Francophone testimony - 1979-80

Gilbert Achcar has argued that the origins of the new version of the term were in the declarations of a Tunisian nationalist and then the work of French Islamic scholars.

- “The first recorded use of “Islamism” in the new sense occurred in 1979 in an article published in Le Nouvel Observateur (12 March) by Habib Boularès, a Tunisian nationalist who had been a member of the cabinet under Habib Bourguiba in 1970–71 and was to join the Tunisian government again under Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. His assessment of what he called “Islamism” was not apologetic, of course. The term then found its first use in the realm of French scholarly Orientalism under the pen of Jean-François Clément in 1980.

- Clément was quite unsympathetic to the movements he described. Thus a further paradox is that the term “Islamism” itself, before it became the pet label of the “Orientalists in reverse”, was first applied to the new generation of Islamic fundamentalists by authors who despised them. These authors merely wanted to cover, with a single word, the whole spectrum of political currents raising the banner of Islam, from the most progressive to the most fundamentalist/intégriste (a term they did not refrain from using). By providing scholarly legitimation to the application of the label “Islamism” to various political movements referring to Islam, many of them violent and fanatical, they contributed to the confusion increasingly fostered by unscrupulous mass media between the religion of Islam and some peculiar and detestable uses made of it.[4]

The Jerusalem Conference - 1979

Historically speaking the Israeli government has fostered the idea of the terror threat meaning the threat of violence from the Palestinians (and the Arabs more generally) and later this morphed into the threat from specifically Islamic or ‘Islamist’ terror.[5]

Thus there is not just considerable overlap between the view of the US and other Western states with those of Israel, but we can also observe a significant effort by Israel to spread the gospel to the US and more widely. As Deepa Kumar shows the effort to tie the Arabs to terrorism was prosecuted at the Jerusalem Conference on International Terrorism in 1979: ‘At this stage the emphasis was on the PLO and the conflation of Arabs with terrorism. Only one presenter spoke about ‘Islamic terrorism’, and overall, Islam was marginal to the conference’.[6] That speaker was Mordechai Abir, whose talk was entitled ‘The Arab World, Oil and Terrorism’. He was later associated with the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs.

He continued to be keen on the thesis that Muslims were driven by resentment of non Muslims and backwardness. In 1994 in an interview he told Manfred Gerstenfeld chairman of the Board of Fellows of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs:

- Since the 19th century, Abir says, some Western philosophers, such as Ernest Renan in France, have accused Islam of being reactionary and standing in the way of the modernization of the Moslem world. This, Renan said, was the cause of Moslem backwardness in modern times and the Moslems' inability to develop and improve their standard of living. Moslem reaction prevents the adjustment of its followers to the new world. The present reality, Abir notes, bears this out.[7]

Militant Islam - 1979

In September 1979 the Levant correspondent for the Economist published a book on Militant Islam, which would appear to have been completed by 'March-June' 1979 according to the epilogue. The book used the phrase 'pan-Islamism' in a citation and then referred on one further occasion to 'Islamism': 'What the Muslim reformers, or at least the Muslim Brotherhood, would like to see is something they call Islamism'(emphasis in original)[8] 'In this scheme', wrote Jansen, 'the "bricks" of a new order for the Muslim world would be Islamic states not national states, which would move through regional co-operation to overall Islamic unification. but even this nebulous plan is something that us said to be for the distant future'[8] Jansen does use the term 'Islamist' or 'Islamists' on 15 occasions but it is reserved only for students of Islam.

Martin Kramer - 1980

Four years after Bernard Lewis's piece in Commentary, Martin Kramer - both student and friend of Lewis - introduced the term 'Political Islam'

- Terminology for the phenomena characterized as Political Islam varies among scholars. The first scholar to introduce the term Political Islam was Martin Kramer in 1980. Some scholars use the term Islamism for the same set of phenomena, or use the two terms interchangeably. Dekmejian 1980 was among the first to place the politicization of Islam in the context of the failures of secular governments, although he uses the terms Islamism and fundamentalism (rather than Political Islam) interchangeably. Dekmejian 1995, still using fundamentalism and Islamism, is an influential treatment of Political Islam as increasingly mainstream and moderate. Some scholars, using descriptive terms such as conservative, progressive, militant, radical, or jihadist, distinguish among ideological strains of Political Islam.[9]

It can be noted that in his 1980s piece[10] Dekmejian does not in fact use the term Islamism or Islamist, though he does use Fundamentalism (twice) and fundamentalists (once). In his later 1995 book (2nd Ed.) the term Islamism or Islamist appears almost 900 times and variations on 'fundamentalist' about 240.[11]

Kramer's 88 page pamphlet was published by Sage but in a series called the 'Washington Papers'. This was edited by Walter Laqueur the historian, journalist, propagandist and 'terror expert' who was at the time attached to the Georgetown University think tank the Center for Strategic and International Studies. The book only used the term 'Islamism' on four occasions, in each case with the prefix 'Pan' as in 'Pan-Islamism'. the idea that Muslims involved in politics might all be part of the same phenomenon seems to have been an intoxicating one. In the Preface Kramer pays tribute to Bernard Lewis, 'who encouraged this study'. 'I know' he wrote 'no finer teacher or friend'.[12]

The Second Conference on International Terrorism - 1984

The Second Conference on International Terrorism was held in Washington DC and the topic of the association of Islam with terrorism was explicitly on the agenda. In his opening address Netanyahu mentioned specifically the threat of ‘Islamic (and Arab) radicalism’.[13] There was a specific session on the ‘Islamic world’ amongst four on the first day. The others dealt with terrorism and democracy, totalitarianism and the international network of terrorism. The session on ‘terrorism and the Islamic world’ was chaired by Bernard Lewis, sometimes referred to as one of the ‘gang of four’ scholars in the field who ‘believed that Western policy towards the Arab world was distorted by sentimental illusions—notably, that it mistook the tyranny imposed by Arab nationalist regimes for progress.’[14] The three panellists in that session were the other three members of the ‘gang’: Professor John Barrett Kelly (then at the Heritage Foundation having left academia a decade earlier to act as a consultant for Gulf State dictators), PJ Vatikiotis (then at SOAS in London) and Elie Kedourie (then at the LSE in London). All four were of course also highly critical of Islam. Lewis is known for his Islamophobia – effectively denounced on many occasions by Edward Said.[15] Kelly, though, thought him ‘much more admiring and much more tolerant of Islamic civilization than I have allowed myself to be’.[16]

Gilles Kepel and Olivier Roy

Gilles Kepel and Olivier Roy, both French academics helped to give the term Islamist currency in early adoptions of the term. Kepel wrote a piece in a French journal in 1984 focused on Egypt.[17] Meanwhile Roy wrote three early pieces in 1983/4, all focused on the Afghan conflict.[18] Kepel and Roy eventually fell out over their differing views.[19]

Kepel's first book, The Prophet and the Pharoah: Muslim Extremism in Egypt, translated into English in 1985, featured a foreword from Bernard Lewis.[20]

Central Asian Survey - 1982

When Roy published his first piece in Central Asian Survey, the fledgling journal was in its second year. According to Kuzio, 'Enders Wimbush and Marie Broxup founded and directed the Oxford-based Society for Central Asian Studies that published the journal Central Asian Survey and Russian language books on Islamic problems, many of which were smuggled into the USSR.'[21] This appears to have been a propaganda operation funded by the US government.

According to Kuzio:

- the Rand Corporation think tank received U.S. government funding to publish studies on nationality problems in the Soviet armed forces. Some of the scholars who authored these articles went on to publish books predicting growing nationality problems in the USSR, particularly due to the Soviet demographic dynamic turning in favor of the Islamic peoples of Central Asia and Azerbaijan.[21]

Immediately before setting up the Society in Oxford UK, Wimbush had been 'a Senior Analyst for the Rand Corporation and led its pioneering studies on nationality problems in the Soviet armed forces.'[21] Indeed after his role in Oxford he went on to work from 1987–1993 as Director of Radio Liberty in Munich, Germany.[22]

Among those in receipt of the funding Kuzio[21] identifies Hélène Carrère d'Encausse, Wimbush, Broxup and her father Alexandre Bennigsen with whom she wrote one of the products of the largesse.[23]

Bennigsen was a key figure in US covert ops against the USSR. He was a close collaborator of CIA operative Paul Henze who was the CIA representative on the National Security Council in the Carter Whitehouse between 1977 and 1980. After retiring from the CIA Henze continued to be involved in related work.

Institute for the Study of Conflict - 1985

Among the authors in the first issue of Central Asian Survey was a writer on Afghanistan Anthony Hyman, who went on to be an associate editor of the journal. Hyman has establishment connections via a fellowship at Chatham House, but an indication that he was perhaps more deeply involved was that he wrote a pamphlet in the series Conflict Studies on 'Muslim Fundamentalism' (1985) for the Institute for the Study of Conflict an MI5/CIA propaganda project.

Resources

- Dekmejian, R. Hrair. “The Anatomy of Islamic Revival: Legitimacy Crisis, Ethnic Conflict and the Search for Islamic Alternatives.” The Middle East Journal 34, no. 1 (1980): 1–12.

- Krieg, Andreas Laying the ‘Islamist’ bogeyman to rest Lobelog, October 10, 2019

- Ganji, B. (2006). Politics of confrontation: the foreign policy of the USA and revolutionary Iran. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Kalinovsky, A. M. (2015). Encouraging resistance: Paul Henze, the Bennigsen school, and the crisis of détente. In Michael Kemper, Artemy M. Kalinovsky (Eds.) Reassessing Orientalism: Interlocking Orientologies during the Cold War (pp. 211-232). Routledge.

- Martin Kramer, The Islamism Debate (Dayan Center Papers, no. 120). Tel Aviv: The Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies, 1997.

- Kramer, Martin. “Coming to Terms: Fundamentalists or Islamists?” Middle East Quarterly 10, no. 2 (2003): 65-77.

- Kramer, Martin. “Islam and Islamism: Western Attitudes Since 9/11.” In Democracy, Islam and the Middle East, edited by Amnon Cohen, 63-70. Jerusalem: The Harry S. Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2005.

- Lewis, Bernard, “The Return of Islam.” Commentary 61, no. 1 (1976): 39–49.

- Reyna, S. P. (2016). Deadly contradictions: The new American empire and global warring. Berghahn Books.

- Sayyid, Salman, (2015). A fundamental fear: Eurocentrism and the emergence of Islamism. Zed Books Ltd.

- Scardino, Albert, 1-0 in the propaganda war The Guardian, 4 February 2005.

- Smith, Blake, Why We Say ‘Islamism’ and Why We Should Stop, Quillette. 11 February 2018.

Articles using the term 'Islamist' or 'Islamism' or similar

- JANSEN, G. H., (1979). Militant Islam'. Pan Books. London/Sidney.

- Jean-François Clément, ‘Pour une compréhension des mouvements islamistes’, in Esprit, January 1980, pp. 38–51.

- Martin Kramer (1980) Political Islam, Sage.

- Clément, J. F. (1980). Problèmes de l'Islamisme. Esprit, (46 (10), 11-38.

- CLEMENT, J. (1983). JOURNALISTS AND SOCIAL-SCIENTISTS VIS-A-VIS ISLAMIST MOVEMENTS. ARCHIVES DE SCIENCES SOCIALES DES RELIGIONS, 28(55), 85-104.

- Roy, O. (1983). Sufism in the Afghan resistance. Central Asian Survey, 2(4), 61-79.

- KEPEL, G. (1984, January). CONTEMPORARY EGYPT-THE ISLAMIST MOVEMENT AND THE LEARNED TRADITION. In ANNALES-ECONOMIES SOCIETES CIVILISATIONS (Vol. 39, No. 4, pp. 667-680). 54 BD RASPAIL, 75006 PARIS, FRANCE: LIBRAIRIE ARMAND COLIN.

- Roy, O. (1984). The origins of the Islamist movement in Afghanistan. Central Asian Survey, 3(2), 117-127.

- Roy, O. (1984). Islam in the afghan resistance. Religion in Communist Lands, 12(1), 55-68.

- Hermassi, M. E. (1984). La société tunisienne au miroir islamiste. Maghreb Machrek: monde arabe, (103), 39-56.

- Waltz, S. E. (1984). THE ISLAMIST CHALLENGE IN TUNISIA. Journal of Arab Affairs, 3(1), 99.

- Hoffman, V. J. (1985). ‘An Islamist Activist: Zaynab al-Ghazali. Women and the Family in the Middle East: New Voices of Change.

- Hassan, R. (1985). Islamization: An analysis of religious, political and social change in Pakistan. Middle Eastern Studies, 21(3), 263-284.

- Makdisi, J. (1985). Legal logic and equity in Islamic law. The American Journal of Comparative Law, 33(1), 63-92.

- Alexander, D. (1985). Is fundamentalism an integrism?. Social Compass, 32(4), 373-392.

- Hyman, A. (1985). Muslim fundamentalism (No. 174). Institute for the Study of Conflict.

- KRAMER, M. (1986). THE PROPHET AND PHARAOH-ISLAMIST MOVEMENTS IN CONTEMPORARY EGYPT-FRENCH-KEPEL, G.

- SARWAR, G. (1986). ISLAM IN REVOLUTION: FUNDAMENTALISM IN THE ARAB WORLD.

- Osman, F. (1986). Modern Islamist and Democracy. ARABIA vom Mai.

- Zubaida, S. (1988). An Islamic State? The Case of Iran. Middle East Report, 3-7.

- Roberts, H. (1988). Radical Islamism and the dilemma of Algerian nationalism: The embattled Arians of Algiers. Third World Quarterly, 10(2), 556-589.

- Ahmad, F. (1988). Islamic reassertion in Turkey. Third World Quarterly, 10(2), 750-769.

- Zouari, A. J. (1989). The effects of Ben Ali's democratic reforms on the Islamist movement in Tunisia (Doctoral dissertation, University of Washington).

- Taraki, L. (1989). The Islamic resistance movement in the Palestinian uprising. Middle East Report, 30-32.

- Kentel, F. (1989). La Société turque entre totalitarisme et d́émocratie: étude de la transformation des intellectuels révolutionnaires et islamistes (Doctoral dissertation, Paris, EHESS).

Notes

- ↑ Militarist Monitor, Bernard Lewis, last updated: September 17, 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Lewis, Bernard, “The Return of Islam.” Commentary 61, no. 1 (1976): 39–49.

- ↑ Hamid Dabashi Alas, poor Bernard Lewis, a fellow of infinite jest, Al Jazeera, 28 May 2018.

- ↑ Gilbert Achcar. “Marxism, Orientalism, Cosmopolitanism”. Apple Books.

- ↑ Brulin, R. (2015). Compartmentalization, contexts of speech and the Israeli origins of the American discourse on “terrorism”. Dialectical Anthropology, 39(1), 69-119.

- ↑ Deepa Kumar, Islamophobia and the politics of empire. Chicago: IL, Haymarket Books, 2012, p. 119.

- ↑ Islamic Fundamentalism, The Permanent Threat:An Interview with Mordechai Abir From Manfred Gerstenfeld: Israel's New Future - Interviews (1994)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jansen, G. H. (1979). Militant Islam. Harper & Row. p. 132.

- ↑ John O. Voll, Tamara Sonn Political Islam Oxford Bibliographies, LAST REVIEWED: 29 SEPTEMBER 2014, LAST MODIFIED: 14 DECEMBER 2009 DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780195390155-0063.

- ↑ Dekmejian, R. Hrair. “The Anatomy of Islamic Revival: Legitimacy Crisis, Ethnic Conflict and the Search for Islamic Alternatives.” The Middle East Journal 34, no. 1 (1980): 1–12.

- ↑ Dekmejian, R. Hrair. Islam in Revolution: Fundamentalism in the Arab World. 2d ed. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1995.

- ↑ Martin Kramer, Political Islam, 1980, Sage:Beverly Hills, CA. p. 8.

- ↑ Deepa Kumar, Islamophobia and the politics of empire. Chicago: IL, Haymarket Books, 2012, p. 119.

- ↑ J B Kelly Fighting the Retreat from Arabia and the Gulf: The Collected Essays and Reviews of J.B. Kelly, Vol. 1 2013.

- ↑ Said, E. W. (2008). Covering Islam: How the media and the experts determine how we see the rest of the world (Fully revised edition). Random House.

- ↑ Deepak Lal, Wisdom on the Greater Middle East, Quadrant, 11th September 2016.

- ↑ KEPEL, G. (1984, January). CONTEMPORARY EGYPT-THE ISLAMIST MOVEMENT AND THE LEARNED TRADITION. In ANNALES-ECONOMIES SOCIETES CIVILISATIONS (Vol. 39, No. 4, pp. 667-680). 54 BD RASPAIL, 75006 PARIS, FRANCE: LIBRAIRIE ARMAND COLIN.

- ↑ Roy, O. (1983). Sufism in the Afghan resistance. Central Asian Survey, 2(4), 61-79.; Roy, O. (1984). The origins of the Islamist movement in Afghanistan. Central Asian Survey, 3(2), 117-127.; Roy, O. (1984). Islam in the afghan resistance. Religion in Communist Lands, 12(1), 55-68.

- ↑ Adam Nossiter ‘That Ignoramus’: 2 French Scholars of Radical Islam Turn Bitter Rivals New York Times 12 July 2016.

- ↑ Bernard Lewis, 'Preface' in Kepel, G. (1985). The Prophet and the Pharoah: Muslim Extremism in Egypt. London: Al Saqi Books.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Kuzio, T. (2012). US support for Ukraine’s liberation during the Cold War: A study of Prolog Research and Publishing Corporation. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 45(1-2), 51-64.

- ↑ Jamestown Foundation S Enders Wimbush. Accessed 18 February 2020.

- ↑ Bennigsen, A., Broxup, M., 1983. The Islamic Threat to the Soviet State. Croom Helm, London.