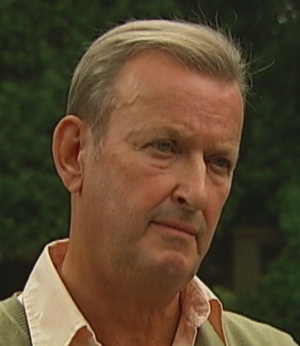

Roger Pearce

This article is part of the Undercover Research Portal at Powerbase - investigating corporate and police spying on activists

Roger C Pearce is a former undercover police officer who rose to be Commander of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch (MPSB) and Director of Intelligence. Since retiring he has become an author of fiction.

As 'Roger Thorley' he infiltrated anarchist groups from 1979 to 1984. From 1980-1981 he wrote articles for the Freedom periodical It seems that Pearce used Freedom to get access British connections with the radical community in Northern Ireland. After a fact-finding mission to Belfast he disappeared from sight.

* This profile is an ongoing project; if you remember 'Roger Thorley' either in the UK or in Northern Ireland, or if you know where he resurfaced later in his deployment period, up to 1984, please get in touch with either Freedom Press or with the Undercover Research Group.

++++++++++Last Updated in 2019, before any disclosure by the Undercover Policing Inquiry ++++++++++

Contents

Police career

Graduating Durham University, Pearce initially looked at becoming an Anglican priest. However, following a placement at the local prison he was inspired to become a police officer, joining Durham Constabulary in 1973.[1] In 1975 he moved to the Metropolitan Police, and applied to join Special Branch the following year.[2]

Of his early attraction to Special Branch, he told the Daily Mail:[1]

- What intrigued me was the very varied and interesting people who joined it. They came from all walks of like. Double honours graduates to guys who left school at 16. And everything in between. They joined because they really enjoyed the work, not because they wanted to climb the greasy pole. And the other side of it was that the work was so very interesting… cases involving national security. I really liked the idea of the secrecy and covert nature of the work. Most of us guys who worked in the Branch found our home there.

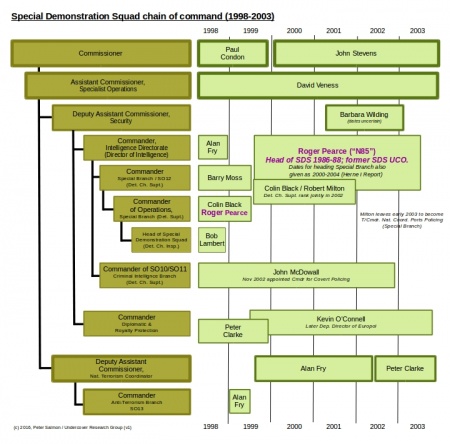

From 1978 to 1980 he was an undercover officer for the Special Demonstration Squad (by which point he was married), and as Detective Chief Inspector was its head in 1986 to 1988,[3] a time when he would have overseen the second parts of the deployments of undercovers Bob Lambert and Mike Chitty. In an interview, he described the SDS:[4]

- The objective was to gather secret political intelligence, information that couldn't be obtained by other means. Many in the Met as a whole wouldn't have known about it, and even within the Branch it was kept very, very secret for 40 years.... Through-out its history very few knew about its work.

He first came to the public's attention in January 1988, when it emerged that, as a detective inspector, he and another Special Branch officer, Detective Sergeant Michael J. Todd[5] visited the workplace of Zeynep Dikmen. Dikmen, a refugee dissident, had taken part in a peaceful hunger-strike outside the Turkish Embassy in relation to the holding of 15,000 political prisoners in that country, in September 1987. Pearce and Todd, described as being of Anti-Terrorist Squad (SO13), had gone to Dikmen's employers, the Turkish Education Group, to ask about her political activities. As a result, she feared her right to stay was under threat and filed a formal complaint.[6]

It appears that he remained with Special Branch for the rest of his career,[7] where he held rank of Detective Superintendent by 1998 as OCU Commander in 1998 and 1999.[8][9] He retired in June 2003.[10]

Undercover Deployment

In March 2018, the chair of the Undercover Policing Inquiry John Mitting revealed that Pearce as 'Roger Thorley' - formerly know only by the cypher HN85 - had operated as a writer for the anarchist periodical Freedom in the 1970s and 1980s.[11] With this, the Friends of Freedom Press was accepted as a 'core participant' in the the Inquiry. The former chair, Christopher Pitchford had refused to do this when they first applied back in October 2015; Mitting now wrote that in the original ruling Pitchford 'would not have taken into account Operation Herne interview notes, which suggest that HN85 became editor of Freedom Press in Whitechapel and in that capacity wrote virulent anti-police articles'.[12]

This profile on Pearce's time undercover as 'Roger Thorley' is based on research by the current Freedom collective, published soon after the Inquiry's confirmation.[13] Looking through the Freedom archive and cross-checking with former collective members, they found that the undercover, writing under the moniker R.T, penned a series of articles over the course of the period 1980-81. He then joined a fact-finding mission to Belfast, before disappearing from sight.

It is as yet unclear where he spent the rest of his time undercover, until 1984.

Personality

'Anarchists who were active at the time do not, for the most part, remember Pearce very well — he seems to have kept a relatively low profile — and as far as can be told he was never an active editor at the paper. Some memories do survive however, which fit with what we now know to have become the standard operating procedure for Met infiltration of perfectly legal, poorly resourced organisations.'

'Dressed up with Trotskyish glasses and a goatee, Pearce was conspicuously “useful” as a car driver prepared to give people lifts (this is a recurring theme from spycops) and one comrade remembers that he was the “unofficial chauffeur” of Leah Feldman, a grandee of earlier times in the movement who, it was said, had been at the funeral of Peter Kropotkin 60 years earlier. Other memories place him as having a girlfriend who was also an activist, though this can’t be confirmed.'[13]

Penning articles for Freedom

Going through the archives, the Freedom collective discovered that Thorley had written a series of articles for their paper. 'Most of these essays were dryly written, but heavily critical assessments of the policing and justice systems with a focus on the situation in Northern Ireland, suggesting among other things that IRA members detained by Britain should be treated as political prisoners — a major and controversial demand of Republican combatants at the time. Pearce qualified as a barrister with Middle Temple in 1979, meaning he was ideally placed to act as an “expert voice” on such matters when putting forward such articles for publication.'[13]

- Freedom has made the 'Roger Thorley' articles available for download (pdf).

Pearce’s writing was specifically in favour of the IRA. 'In one article, Prisoners of Politics,[14] the editors debate “R.T” over his demand that IRA detainees should have political prisoner status, noting that “all prisoners are political”. In another he attacks the arrest of Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, as “difficult to evaluate in terms of sheer blatant prejudice and hysteria,” comparing him to Provisional IRA man Gerard Tuite.'[13]

'But it is R.T’s final article which should raise the most eyebrows. In The Not So Distant Struggle[15], he reports back from a fact-finding mission to Belfast that he had inveigled himself onto, along with four other members of the Freedom Collective. The consummate London police spy’s empathetic report on the Troops Out phenomenon, which suggests a close working relationship with the then-active Belfast Anarchist Collective, notes:

- Within a short distance of Britain we are daily witnessing a most repressive regime whose intensity supports no comparison with life in London; a regime where there is near total monitoring of movement day and night, where constant use is made of the Prevention of Terrorism Act to detain and prosecute ‘political offenders’, where the overt presence of armed forces often reaches saturation point, where prisoners are condemned by juryless Diplock courts, and where widespread condemnation has been directed internationally, particularly from America.'[13] (N.B. Diplock courts were a type of court established by the Government of the United Kingdom in Northern Ireland on 8 August 1973 during The Troubles. The right to trial by jury was suspended for certain "scheduled offences" and the court consisted of a single judge.)

'A paid-up member of the British state writing to the public that:

- Ideological scruples must not be allowed to erode the clear responsibility of focusing attention on what has become the embodiment of the repressive state visibly at work in utilising all its resources, using the streets of Belfast, Derry and elsewhere as a prime testing ground for future urban unrest in Britain.

- In doing so, the striking image of people demanding to determine their own existence emerges not just from individual IRA actions, but rather from the close communities of which the IRA guerrillas are an indissoluble part.

It’s an analysis many anarchists and leftists would agree with, then and now. But for an agent of the Crown, misleading would be an understatement.' the Freedom paper wrote.[13]

Activities abroad?

The strong implication, and one which Freedom is investigating, 'is that Pearce was using the paper as a way to contact and assess British connections with the radical community in Northern Ireland in a period of crisis. The news will strengthen the case for an expansion of the inquiry into the region or have a separate there, as Pearce joins other undercovers with links to Northern Ireland and would go on to become the Met’s Director of Intelligence and head of Special Branch from 1998-2003'.[13]

- Also see our profile on Rick Gibson, who infiltrated the Troops Out Movement in London from 1974 - 1976, a couple of years before 'Roger Thorley' went undercover. It should be noted that the TOM was a battlefield of Trotskyist factions, far removed from anarchist circles. Troops Out was a demand widely supported though.

- For more on Leah Feldman, see Tom Coburg, ‘Spycop’ scandal hits new low with claim that officer exploited elderly activist as part of cover, The Canary, 27 March 2018.

Director of Intelligence

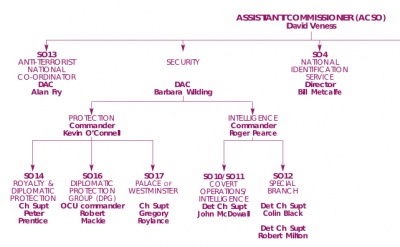

Roger Pearce was appointed Director of Intelligence (SO11) on 2 November 1998 and held it until 4 March 2003.[16] In 1999, Pearce was appointed head of Special Branch (SO12) and held both posts concurrently until his retirement in 2003.[3][2][17] In this latter role he also had oversight of the Covert Operations unit SO10.[18]. As Head of Special Branch he was:[19]

- ... responsible for surveillance and undercover operations against terrorists and extremists, the close protection of government ministers and visiting VIPs, and other highly sensitive assignments...

Additionally, his role as Director of Intelligence 'charged [him] with heading covert operations against serious and organised criminals'.[19]

His line manager was Deputy Assistant Commissioner (Security) Barbara Wilding, who in turn answered to the Assistant Commissioner Specialist Operations David Veness. [20]

Undercover policing

As Director of Intelligence, Pearce had responsibility for 'authorising surveillance and undercover operations' in the Metropolitan Police,[2] and as part of this role to he would 'sign off almost every undercover operation carried out by the SDS'.[21] This means he had responsibility for the undercover officers deployed by the Special Demonstration Squad, who at the time included Simon Wellings, Carlo Neri, Jason Bishop - amongst others. It is likely that the deployment of another known undercover, 'N81', overlapped in this period as well.[22]

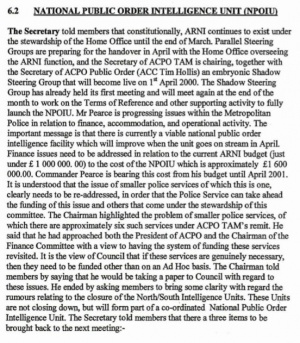

Establishment of NPOIU

In 1999, the National Public Order Intelligence Unit was created as a national extension of the Special Demonstration Squad. Though done under the aegis of the Association of Chief Police Officer's Terrorism and Allied Matters committee (ACPO TAM), the lead officers on it were David Veness and then Special Branch Commander Barry Moss. Thus, for the first two years of the unit's life it was based in the Metropolitan Police Special Branch, where it was developed as an extension of the Animal Rights National Index (nominally under the 'stewardship' of the Home Office. It would remain so until April 2001, when control formally transferred to ACPO TAM.

Pearce replaced Moss as Head of Special Branch in 1999, and as such held ‘operational resourcing and leadership of the [NPOIU] during the transitional phase'. This was done jointly with Paul Blewitt of West Midlands Police,[23] though specifically Pearce oversaw the development of the NPOIU into an operational unit and it was his department that met the costs. It was later noted by HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, that this was a period when both the SDS and NPOIU shared connections through people and resources.[24]

From this it can be deduced that Pearce was a member of ACPO TAM while head of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch. Furthermore, given his role overseeing the NPOIU, it is likely that Pearce also sat on the NPOIU Steering Group set up by ACPO TAM. Other members were Tim Hollis, Assistant Chief Constable for South Yorkshire Police and Paul Blewitt, Assistant Chief Constable for Operations at West Midlands Police, both of whom represented ACPO's Public Order Committee. (Blewitt would later join former undercover officer John Dines at Charles Sturt University in Australia as an Industry Fellow in its School of Policing Studies.[25])

Likewise, Pearce's involvement in NPOIU implies that he would have had knowledge of undercovers deployed at the time by that unit. These include Rod Richardson (1999-2003), Lynn Watson (2002-2006) and Mark Kennedy (2003-2009). In particular, it is highly likely he would have had responsibility for signing-off Rod Richardson's deployment. Though given the transfer of control over the organisation, it is less clear who was responsibile for authorising Watson and Kennedy.

BBC True Spies documentary

In 2002, Peter Taylor made a three part BBC series, True Spies. At the time, the Metropolitan Police was happy to co-operate with the programme on undercover policing and encouraged former undercover officers to be interviewed on camera about their work.

As head of Special Branch, Pearce strongly supported the making of True Spies,[26] and sent a letter on 17 October 2002 to former SDS officers to make them aware of the show:[27]

- The Metropolitan Police has been keen to support this project, and on the basis of firm reassurances from the programme makers that operational and personal security would not be compromised, an invitation was extended to former Special Branch officers to contribute to it in any way they thought fit...

- As a former SDS officer, I know that you will have a particular interest in the series and I thought it might be helpful to offer a brief advance summary of its content, specifically from the perspective of the SDS unit:

- ... A section of the programme will outline the formation of the SDS and a number of former SDS officers are interviewed on screen (none more recent than 1985). Legend building, tradecraft and areas of targeting are among the issues highlighted and discussed in the first programme.

- For more detail on the full cooperation of the Metropolitan police with the BBC, see the True Spies - Story

Spying on Duwayne Brooks

In 2014, the Ellison Review into undercover policing looked into the allegations that black justice campaigns had been spied upon, in particular the family of Stephen Lawrence, and his friend Duwayne Brooks. At the time, 2000, tensions around the investigation into the death of Stephen Lawerence remained high. The Review revealed that on 24 May 2000, DCI Michael Jones was authorised by DAC John Grieve of the Racial and Violent Crimes Task Force to covertly record a meeting with police at the offices of Brook's solicitor Jane Deighton that day. The recording is known to have taken place as there was a transcript of the conversation. The application was made on the basis that:[28]

- Such deployment will also provide a precise record of any conversation, which might be necessary to counter any future allegations of criminality or conspiracies on the part of the police.

Jones would make a second application to bug a meeting with Brooks and Deighton due to take place on 16 August 2000, though it was not known if it was actually recorded or authorised. In this case the 'request for authority was directed to the then Director of Intelligence'[28] - who at that point would most likely have been Roger Pearce.[29]

Applications in relation to two other witnesses in the Stephen Lawrence murder inquiry were also made, though again it is not clear from the Ellison Review to whom the applications were made, whether authorisation was granted, or whether recording took place. Ellison concluded that though the covert recording was not unlawful, 'we do not believe that such a tactic was necessary or justified in the circumstances'.[28]

Other notable activity as Director of Intelligence

- 2000: Ex-MI5 officers and whistleblowers David Shayler and Annie Machon, called on Pearce to investigate a 1996 plot by MI6 officers to kill the Libyan ruler Muammar Gadhafi and provided a dossier of evidence.[30] Pearce responded to Shayler's lawyer John Wadham[31] on 14 August, saying the evidence was being 'assessed' rather than investigated. It also asked that Shayler, then in exile in France, return to the United Kingdom so he could be interviewed.[32][33][34] Returning from France, Shayler was interviewed by police and signed a lengthy statement, and in 2001 police sent a report to the Crown Prosecution Service, though no further action appears to come from this.[35]

- August 2001: Special Branch officers under Pearce were responsible for arresting security guard Raphael Bravo, who had been caught in a joint Special Branch / MI5 sting trying to sell BAe military secrets to the Russians.[36][37]

- In February 2009 Pearce gave evidence in an Information Tribunal case, on behalf of the Metropolitan Police, in his role as a former Commander of Special Branch. In this matter, a historian was appealing the refusal of Special Branch to release files on the infiltration of anarchist groups from late 1800s to early 1900s and the inconsistency of Special Branch policy on access was being examined.[10]

Commentary on undercover work

As a high ranking former Special Branch officer who had put himself in the public eye over his authorship of police thrillers, Pearce has been asked on several occasions to respond to the undercover policing scandal.

In May 2012, in an interview around the publication of his first book, Pearce is quoted as saying:[38]

- However negligent and dishonest people might think those in the police and secret services may be, there are always people who will go to any length to protect the public. Although there is corruption, or has been corruption, there are people within those organisations who will do all they can to keep people safe. Corruption was a very big problem in the Seventies, but the Met have taken the strongest steps to expose it. There is a need for secrecy, but I strongly feel that where there are failings the public need to know as it affects their safety.

On Peter Francis and spying on the Lawrence family

When the Ellison Review found that the family of Stephen Lawrence had indeed been spied upon by the SDS, Pearce appeared in an interview for Channel 4 News to challenge the statements of SDS whistle-blower Peter Francis who had originally made the allegations.[7] Though he had known Peter Francis, who had been undercover in anti-racism groups in the mid-1990s,[39] Pearce had not been Francis' boss at the time of his deployment.[7]

In relation to the Lawrence family justice campaign, Pearce claimed instead that:[7]

- The concern would be that the extreme Right or elements of the extreme Left would hijack the campaign, infiltrate it and use it for their own ends. The real concern was that this would lead to public disorder.

He also denied there had been tasking of undercovers to seek material the family could be smeared with,[39] and said that Francis' claims in relation to that were 'incomprehensible'.[40] In particular he stated:[41]

- Undercover officers often do work at great expense to themselves. There is a sense of mission about what they do for the sake of the country. They experience problems in family life and their careers.

I knew Peter in the 1990s. He was an effective and resourceful undercover officer, known for excellent trade craft. But I would be astounded if it is proved that someone said: "Go out and get information to rubbish and smear the Lawrence campaign."

- Undercover officers often do work at great expense to themselves. There is a sense of mission about what they do for the sake of the country. They experience problems in family life and their careers.

On use of dead children's identities

The use of dead children's identities was an established part of the tradecraft for SDS undercovers for many years, with as many as 80 false identities created in this way.[42] The Home Affairs Select Committee made trenchant criticism of the practice in 2013, stating:[43]

- The practice of "resurrecting" dead children as cover identities for undercover police officers was not only ghoulish and disrespectful, it could potentially have placed bereaved families in real danger of retaliation. The families who have been affected by this deserve an explanation and a full and unambiguous apology from the forces concerned. We would also welcome a clear statement from the Home Secretary that this practice will never be followed in future.

Pearce responded in a BBC interview, explaining that though distasteful, the practice was justifiable to create a 'real persona' the necessary driving licences, national insurance numbers, etc.:[21]:

- If you were inviting people to lead a false life, they had to have a true identity. They had to be able to feel secure throughout the deployment, that their identity and legend would stand scrutiny. At that time, before the digital age and before identities could be made up, this was the only way of finding a true alias...

People found it distasteful, even at the time. People felt very awkward about doing it. People thought of the parents of the children who had died. But against that was the sense of mission and work for the country.... On balance, distasteful in many ways though it was, set against the sense of mission and the sense that this was done for protection of national security, I believe it was justified.

- If you were inviting people to lead a false life, they had to have a true identity. They had to be able to feel secure throughout the deployment, that their identity and legend would stand scrutiny. At that time, before the digital age and before identities could be made up, this was the only way of finding a true alias...

Pearce was also interviewed by Operation Herne, the police review into the undercover policing scandal. Its first report (March 2014) focused on the use of identities of dead children. Pearce is quoted as 'N85' (see details on how he was identified as N85 below).[3]

|

On sexual relationships with targets

On being asked in a BBC Radio 4 interview with Melanie Abbott for an issue The Report programme looking at undercover policing, when asked about sexual relationships by undercover officers he responded:[4]

- [Roger Pearce]: Unpalatable as it is, the state, the country, the government, the Branch was inviting individual officers to live a false life for four or five or more years, the false friendship can develop and escalate into a sexual relationship. So it's almost inevitable that these took place and I am making no moral judgement about them at all. It's the decision of the individual officer how he would conduct his time in the field. An undercover officer, on the day he infiltrates he must be thinking about the day of exfiltration several years down the line. If a sexual relationship is involved, this is unlikely to lead in a satisfactory or easy, risk free exit strategy. So there is compromise to the officer always possible, there is the effect upon the activist with whom he's had a sexual relationship and there is the risk to the whole operation.[21]

- [Melanie Abbott]: But was that drummed into the officers who were going undercover?

- [Roger Pearce]: I'm not sure; I dont think it was actually. I think each officer was invited to lead the life in the way he thought best.

Later in the BBC interview, when the issue of undercovers having children with those being targeted was raised, Pearce said he knew nothing about it:

- [Melanie Abbott]: If you had known about it, would you have offered some kind of support to those second families as it where?

- [Roger Pearce]: Well, first of all, I'd want to know the precise detail and context in which this had happened. I suppose I'd want to know the risk to the officer. I suppose I'd want to know the situation of the activist. I'd want to know the state of their relationship.

When pressed on whether should the Met be offering support to those children and to their mothers, he said he was going to duck the question and sit on the fence.

Pearce was also tackled on the issue of sexual relationships in his interview for Channel 4 News. There, the interviewer, Paraic O'Brien described Pearce's view as being that it was an 'unfortunate outcome' and when pressed, Pearce went on to defend the SDS officers, saying:[7]

- The people I know and knew, the people who were selected for Special Branch and above all those who were selected for SDS, with very, very few exceptions who were known about, were people of integrity and honour and fired up by a sense of mission, to protect the country actually.

Media appearances on undercover policing

- 28 June 2013: No attempt to smear Lawrence family' - video, Channel 4 News: interview by Paraic O'Brien. A response to Peter Francis and other issues around undercover policing.

- 2 July 2013 - Roger Pearce interview, Strike Digital. In this interview he focuses on his fiction writing but touches in places on Special Branch.

- 3 July 2013: Radio 5 Live: interviewed by Phil Williams.

- 11 July 2013, The Report: Undercover Police, BBC Radio 4: interviewed by Melanie Abbott.[44]. During this interview, Pearce refused to state that he had been an undercover officer himself, but limited himself to saying that he had known many SDS officers in his time.

- 4 October 2013, Crime Pays! Ex Special Branch chief’s new career as acclaimed thriller writer, Mail Online: interview by Stephen Wright.

Identification of Pearce as undercover officer 'N85'

In Autumn 2016, researchers with the Undercover Research Group realised that it was possible to identify one of the senior officers named in the first Operation Herne Report by piecing together various bits of evidence. However, the research into one of them, N85, brought to light apparent mistakes in the chronology of his career.

The report introduces N85 as a police officer with the rank of Commander and Head of Special Branch 2000-2004.[45] The name to go with this role around that time was Roger Pearce, but sources had him as the Head of Special Branch for a different period: from 1999 to 2003. These sources included ACPO minutes, his own biography at several websites (all cited in this profile) and the recent book History of Special Branch written by Ray Wilson & Ian Adams, two former Special Branch officers.[46] From this, the researchers were able to conclude that N85 was the same as Roger Pearce, and that the authors of the Herne report simply shifted the years, possibly in an effort to obfuscate.

The identification was further lent credence by Pearce’s in-depth of knowledge of the Special Demonstration Squad and its tradecraft, as cited above.[47]

The first Herne Report, stated N85 had also been an undercover officer between 1978-1980, and later Commander of the Special Demonstration Squad between 1986 and 1988.[45] Rob Evans at The Guardian has noted that the Herne report appears to have other inconsistencies in relation to N85 / Pearce, in particular, that his deployment as an undercover was apparently 1979 to 1984.[48] This may also throw doubt on the dates he was listed as head of the SDS.

The identification was first floated in 2014 by blogger and researcher BristleKRS.[49]. In October 2016, the Undercover Research Group published their research and this profile; confirmation by the Undercover Policing Inquiry that Pearce had been an undercover followed in March 2017 (see below).

Update: Within a week after the announcement by the Inquiry, the Metropolitan Police confirmed that the actual dates Pearce served as Director of Intelligence were November 1998 to March 2003; which means the dates in the Operation Herne report are wrong.[16]

In the Undercover Policing Inquiry

On 29 March 2017, the Inquiry into Undercover Policing announced that Roger Pearce would not be seeking anonymity as a former undercover officer, and revealed that his cover name had been 'Roger Thorley'.[50] The first announcement said he had been an undercover officer with the Special Demonstration Squad from 1978 - 1980,[50] In 2018, further details were released and earlier mistakes - as noted by Rob Evans, see above - corrected: Pearce's deployment had been longer. On 18 January 2018, the Inquiry revealed that he had infiltrated anarchist groups from 1979 to 1984.[51] And in March 2018, the chair revealed that as 'Thorley', he had operated as a writer for the anarchist periodical Freedom in the 1970s and 1980s, as detailed above.[52]

Pearce is not a core participant in the Inquiry,[50] and neither his name or cipher has otherwise appeared in documents released by the Inquiry. [53]

Post police career

On his retirement he became the Counter-Terrorism Advisor, a newly formed post at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, working on tackling Al Qaeda.[2] From 2005 to 2012 he was European Security Director for the multinational GE Capital.[2][19]

He has since become a published author, drawing on his experience as a police officer, with two thrillers published by Hodder & Stoughton to date (October 2016), focusing on the character of 'DCI John Kerr'.

- Agent of the State, June 2012

- The Extremist, July 2013

- Javelin, forthcoming

His official website is http://www.roger-pearce.com/

Education

- Queen Elizabeth's School, 1961-1969, School Captain.[2]

- St. John College, Durham University, BA (Hons) in Theology 1972.[2]

- London University, LLB, 1970s.[2]

- Barrister with Middle Temple, qualified 1979.[2]

Other officers of the same name

There appear to be a number of other police officers of the same name around the same time as Roger Pearce was with Special Branch. They do not, however, appear to be the same individual.

- A Roger Pearce oversaw the investigation into the murder of Peter Hayward (?) in 1984.[54]

- Det. Supt. Roger Pearce, investigated the murder of Carmel Gamble in Stroud, Gloucestershire in 1989[55]

- DC Roger Pearce, of City of London Police, was charged with perverting the course of justice in 1998, along with DC Peter Lawson.[56] In 1999, he and Lawson were subsequently charged alongside two other officers, Christopher Drury and Robert Clark in a notable police corruption trial.[57][58]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Stephen Wright, Crime Pays! Ex Special Branch chief’s new career as acclaimed thriller writer, Mail Online, 4 October 2013 (accessed 23 September 2016).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 With the benefit of experience: author Roger draws on his time leading Special Branch, Queen Elizabeth's School website (QEBarnet.co.uk), undated (accessed 31 July 2016).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Mick Creedon, Operation Herne Report 1: Use of covert identities, Metropolitan Police Service, 6 March 2014.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 The Report: Undercover Police, BBC Radio 4, 11 July 2013.

- ↑ This may be the Michael James Todd who became Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police, but this is still to be confirmed.

- ↑ Paul Brown, Protest over questioning of refugee, The Guardian, 16 January 1988 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 No attempt to smear Lawrence family' - video interview of Roger Pearce by Paraic O'Brien, Channel 4 News, 26 June 2013.

- ↑ The Police and Constabulary Almanac 1998, R Hazell & Co, 1999.

- ↑ The Police and Constabulary Almanac 1999, R Hazell & Co, February 1998.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Judgment in case of The Metropolitan Police v Information Commissioner, Information Tribunal, 30 March 2009.

- ↑ Undercover Policing Inquiry, Cover names, updated 20 March 2018, (accessed March 2018)

- ↑ Ruling Core Participant, 20 March 2018 (accessed March 2018)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Freedom News, The Met spychief who infiltrated Freedom, 24 March 2018 (accessed March 2018)

- ↑ R.T, Prisoners of Politics, Freedom, Vol 41, No. 22, 8 November 1980

- ↑ R.T. The Not So Distant Struggle, Freedom, Vol 42 No. 19, 26 September 1981

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Metropolitan Police Service, Directors of Intelligence (SO11) - dates of service, Response to FOIA request of Peter Salmon, 6 April 2017 (accessed 8 April 2017).

- ↑ John Lichfield, Shayler will be arrested when he returns today, The Independent, 20 August 2000 (accessed 29 March 2017).

- ↑ MPA Remuneration Subcommittee, ACPO recruitment 2002, Metropolitan Police Authority, 29 July 2002 (accessed 31 August 2016).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Roger-Pearce.com (personal website), undated, accessed 31 August 2016).

- ↑ SpecialOps/02.08, Metropolitan Police Service, undated (appears to be created 20 August 2001; accessed 2 December 2014).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Police use of dead children's identities 'justified', BBC News Online, 11 July 2013 (accessed 23 September 2016).

- ↑ The controversial meeting between N81, Bob Lambert and Richard Walton of August 1998 which related to spying on the Lawrences is prior to Pearce being appointed head of Special Branch. However, Pearce will have been of rank of Detective (Chief) Superintendent by this stage, most probably occupying a high position in Special Branch's hierarchy.

- ↑ Council Committee on Terrorism and Allied Matters, NPOIU Strategic Overview - Update, Association of Chief Police Officers, 22 January 2000, published at SpecialBranchFiles.UK.

- ↑ A review of national police units which provide intelligence on criminality associated with protest, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, 2012.

- ↑ Paul Blewitt, Profile, LinkedIn.com, 2016 (accessed 22 September 2016).

- ↑ Rob Evans, Leaked letter appears to undermine police bid for undercover secrecy, The Guardian, 18 March 2016 (accessed 31 August 2016).

- ↑ Roger Pearce, Letter of 17 October 2002, archived at SpecialBranchFiles.UK.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Mark Ellison, The Stephen Lawrence Independent Review, Possible corruption and the role of undercover policing in the Stephen Lawrence case, Gov.UK, Vol. 1, March 2014. See in particular Section 7.4.

- ↑ It is of note that John Grieve had been also served as the first Director of Intelligence, in office from 1993 to 1996 when he was succeeded by Alan Fry.

- ↑ Paul Kelso, Shayler gives Gadafy dossier to police, The Guardian, 28 March 2000 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ Wadham, a director of civil rights group Liberty, also made an appearance in the undercover policing scandal as one of those mentioned in 1998 intelligence reports by SDS undercover N81.

- ↑ Richard Norton-Taylor, Shayler returns as Yard investigates Gadafy claims, The Guardian, 21 August 2000 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ John Lichfield, Shayler affair: spy comes in from the cold in a blizzard of lights and cameras, The Independent, 21 August 2000 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ Joshua Rozenberg, I'm no traitor says Shayler as he returns to face charges, The Telegraph, 21 August 2000 (accessed 23 September 2016).

- ↑ Richard Norton-Taylor, Police send report to CPS on 'plot to kill Gadafy', The Guardian, 30 March 2001 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ Richard Norton-Taylor, Security guard jailed for trying to sell secrets, The Guardian, 2 February 2002 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ Security 'spy' gets 11 years, This is Local London, 13 February 2002 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ Kiran Randhawa, Secret service errors must be exposed, says ex-Scotland Yard chief, Evening Standard, 28 May 2012 (accessed 23 September 2016).

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Justin Davenport, We need open inquiry into smear claims, says Lawrence, Evening Standard, 27 June 2013 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ Hayley Dixon, 10 questions for police over Lawrence family smear claims, The Telegraph, 10 July 2013 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ Stephen Wright & Richard Pendlebury, A very troubled undercover cop and growing doubts over the police 'plot' to smear the Lawrence family, Daily Mail, 19 July 2013 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ Paul Lewis & Rob Evans, Police spies stole identities of dead children, The Guardian, 3 February 2013 (accessed 23 September 2016).

- ↑ Home Affairs Committee, Report - Undercover Policing: Interim Report - The use of dead infants' identities, Parliament.UK, 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Copies of this audio are also available here or on YouTube.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Mick Creedon, Operation Herne Report 1: Use of covert identities, Metropolitan Police Service, 6 March 2014, p.14.

- ↑ Ray Wilson & Ian Adams, Special Branch A History: 1883-2006, BiteBack Publishing, 2015.

- ↑ The other senior officer in the picture as a candidate was Det. Ch. Supt. Robert Milton who held a high position in Special Branch and the rank of Temporary Commander in November 2003. However, by that stage he was already on secondment to the Home Office as National Co-ordinator Ports Policing, so it is unlikely he held this post.

- ↑ Rob Evans, How UK police helped unmask one of their own undercover spies, The Guardian, 3 April 2017 (accessed 3 April 2017)

- ↑ BristleKRS, Neither confirm nor deny except when it suits them, Bristle KRS (wordpress blog), 4 June 2014.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Undercover Policing Inquiry, No anonymity sought for Roger Pearce, ucpi.org.uk, 29 March 2017 (accessed 29 March 2017).

- ↑ Cover Names, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 18 January 2018 (accessed 19 January 2018).

- ↑ Undercover Policing Inquiry, Cover names, updated 20 March 2018, (accessed March 2018)

- ↑ See for example, the list of core participants released by the Pitchford Inquiry (accessed October 2016).

- ↑ Clare Campbell, I just couldn't start to live my life again until I'd met my father's killer, Daily Mail, 20 December 1994 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ Police seek help in cottage murder inquiry, Press Association, 13 November 1989 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ Detective is charged, Birmingham Evening Mail, 26 November 1998 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ Dealer 'split drugs cash with policeman lover', The Guardian, 18 November 1999 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ David Wilkes, Five jailed in scandal that rocked the Yard, Daily Mail, 5 August 2000 (accessed via Nexis).