Difference between revisions of "The Risk of Freedom conference"

(Creating new page from the search results page) |

|||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

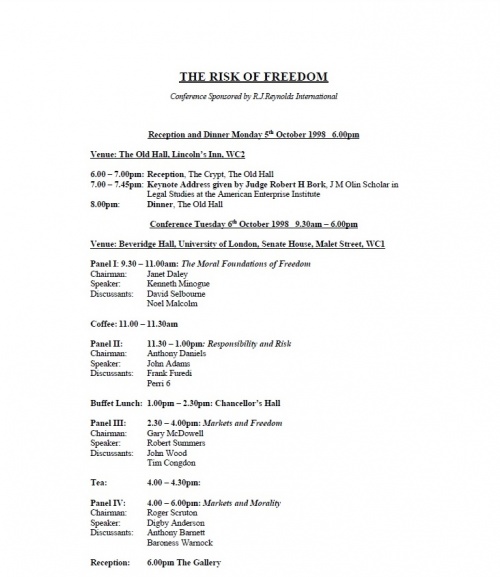

| − | [[File:Risk of freedom conference sponsored by J R Reynolds.jpg|thumb|right| | + | [[File:Risk of freedom conference sponsored by J R Reynolds.jpg|thumb|right|500px|''[[The Risk of Freedom conference]]'', sponsored by ''[[R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company]]'', programme of events, 5-6 October 1998.]] |

| + | |||

| + | [[The Risk of Freedom conference]] was organised by [[Roger Scruton]] for the [[Institute of United States Studies]] and sponsored by tobacco giant [[RJ Reynolds]]. The conference brought together a number of tobacco industry linked libertarian thinkers to present their views on the moral questions regarding freedom, risk, responsibility and markets. Speakers received £1,000 for their services whilst the chairs and discussants also received an honorarium of £300<ref> University Records Manager & FOI Officer [[University of London]], 'Freedom of Information Request for information on: the programme of Lanesborough Luncheons, sponsored by JT international', received 24 March 2011, returned 13 April 2011.</ref>. The conference led to the subsequent [[Lanesborough Luncheons]] and the [[Risk of Freedom Briefing]]'s which reported on these events, although these were sponsored by [[Japan Tobacco International]]. The conference itself ran from Monday 5 October to Tuesday 6 October 1998 with a reception and dinner held on the Monday, followed by a full days conference on the Tuesday. The reception and dinner were held from 6pm at The Old Hall in [[Lincoln's Inn]], which describes itself as 'an active and thriving society of lawyers with a very long history situated in a tranquil enclave of some 11 acres in central London. “Lincoln’s Inn” thus refers both to the Society and the place'<ref>[http://www.lincolnsinn.org.uk/ 'The Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn'], accessed 30 April 2015.</ref>. Judge [[Robert H Bork]] from the [[American Enterprise Institute]] gave a keynote address. | ||

| + | ==Conference== | ||

| + | The Conference was held on Tuesday 6 October 1998 at Beveridge Hall, [[University of London]], Senate House, Malet Street, WC1E 7HU. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *The first session was entitled ''The Moral Foundations of Freedom''. [[Janet Daley]] chaired the panel, which included [[Kenneth Minogue]] as the keynote speaker. They were joined by discussants [[David Selbourne]] and [[Noel Malcolm]]. | ||

| + | *The second session was entitled ''Responsibility and Risk'' and was chaired by [[Anthony Daniels]]. The rest of the panel consisted of keynote speaker [[John Adams]] and the discussants [[Frank Furedi]] and [[Perri 6]]. | ||

| + | *The third session was entitled ''Markets and Freedom'' and was chaired by [[Gary McDowell]]. The keynote speaker was [[Robert Summers]] who was joined by discussants [[John Wood]] and [[Tim Congdon]]. | ||

| + | *The final panel session was entitled ''Markets and Morality'' and was chaired by [[Roger Scruton]]. The keynote speaker was [[Digby Anderson]] who was joined by discussants [[Anthony Barnett]] and Baroness [[Mary Warnock]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The Moral Foundations of Freedom=== | ||

| + | The first lecture was given by Kenneth Minogue and covered by Minogue himself in [[The Independent]]. In this he described the economy as being 'at the heart of the softness of manners and abundance of material opportunities open to us in the modern world'. In addition he argued that only technological innovation had shielded this apparently compassionate economy from the despotic appropriation of its resources by the state. He also argues that societal efforts to tackle inequality in fact demonstrate an attack on freedom, and that the ideas of prejudice, racism and sexism should be presented as 'prejudice', 'racism' and 'sexism' as their existence required a fertile imagination: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%"> | ||

| + | The ground of the state's bid to control the economy was justice. Many thinkers argued that the gap between rich and poor was the great evil of human life. They demanded that the power of the state, whose legitimate point was to secure order for a free people, should now be directed to redistributing wealth. In time, the state began appropriating half of everything an economy produced, a level of rapacity that would have brought tears of admiration to the eyes of the most hardened oriental despot, and tolerable only because of the abundance created by technology....This development emerged from a new theory of the state. Liberal democracies, it was argued, were not civil associations of individuals free to pursue their own desires, but were, rather, a pattern of homogenous units, each with its own specific interests and demands. The clearest example of this theory was the so-called "multicultural" society, in which the units were ethnic groups, taken as "cultures" and constituting the political sub- communities of which the state was taken to be composed...It happened that not all these groups liked or approved of each other, a situation called "prejudice" or, in specific cases, "racism", "sexism", etc. Given a moral ideal of justice as the equal distribution of benefits, including equality between these newly discovered elements of society, the state discovered a duty to engineer a new, improved society exhibiting justice in this sense. Voluntary associations often did not mirror this new sociological composition of British society, and in the name of justice a social plan came down over British life like a mist. The aim was statistical homogeneity as exhibited in wealth, vocational engagement, incidence of prison sentences, health, and any other indicator that might occur to the fertile imaginations of excitable lobby groups speaking for blacks, browns, women, homosexuals, the disabled or any other element in the new plural society<ref>Kenneth Minnogue, [http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/podium-the-nationalisation-of-society-1176970.html 'Podium: The nationalisation of society'], ''The Independent'', 9 October 1998.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | A report on the conference also noted: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%"> | ||

| + | Then there was Professor Kenneth Minogue. He declared the state had made us all slaves (what he would call the unfortunates who live under regimes which deny them democracy or human rights isn't clear), confiding en passant: "Everyone knows that women and ethnic employees are less competent than white males"<ref>Melanie Phillips, 'The Tories are lost while they keep kicking nanny', ''The Sunday Times'', 11 October 1998.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Responsibility and risk=== | ||

| + | The second lecture topic was presented by [[John Adams]] a former member of Friends of the Earth turned climate 'agnostic'. The lecture frequently cited the [[Revolutionary Communist Party]]'s former lead member [[Frank Furedi]]'s work, and the work of the chair of the discussion [[Anthony Daniels]]. The lecture presented risk as being usefully distinguished by three categories, with global warming included in the 'virtual risk' section, which serves to describe risk on which scientists cannot agree: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%"> | ||

| + | * directly perceptible risks: e.g. climbing a tree, riding a bicycle, driving a car, | ||

| + | |||

| + | * risks perceptible with the help of science: e.g. cholera and other infectious diseases, | ||

| + | |||

| + | * virtual risks - scientists do not know or cannot agree: e.g. BSE/CJD, suspected carcinogens, global warming<ref>John Adams, [http://john-adams.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2006/risk,%20freedom%20&%20responsibility.pdf 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility'], Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, Inst. of US Studies, Senate House, 6 October ''1998, Published in The Risk of Freedom: individual liberty and the modern world'', Institute of United States Studies, 1999, p. 3.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Describing 'directly perceptible risks' he argues that safety regulators fail to see the 'rewards' individuals attach to smoking, ignoring that any perceived reward is likely related to the addictive quality of smoking: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%"> | ||

| + | Why do so many people insist on taking more risks than safety authorities think they should? It is unlikely that they are unaware of the dangers - there can be few smokers who have not received the health warning. It is more likely that the safety authorities are less appreciative of the rewards of risk taking<ref>John Adams, [http://john-adams.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2006/risk,%20freedom%20&%20responsibility.pdf 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility'], Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, Inst. of US Studies, Senate House, 6 October ''1998, Published in The Risk of Freedom: individual liberty and the modern world'', Institute of United States Studies, 1999, p. 4.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Adams also seeks to use the example of seat belts to argue that attempts to regulate directly perceptible risks are doomed to failure due to people's instinctive self-management of these risks and that perverse side-affects are caused by regulation. Without actually quoting any statistics he states that: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%"> | ||

| + | There is now abundant evidence, particularly with respect to directly perceived risks on the road, that risk compensation, sometimes referred to as offsetting behaviour, accompanies the introduction of safety measures. Statistics for death by accident and violence, perhaps the best available aggregate indicator of the way in which societies cope with directly perceived risk, display a stubborn resistance, over many decades, to the efforts of safety regulators to reduce them. With directly perceptible risks we encounter an intriguing ambivalence. In Britain both opinion poll evidence and a high level of compliance with the seat belt law suggest that this measure, which is designed to protect people from themselves, enjoys a high measure of popular support. And yet there is compelling evidence that motorists have responded to such measures by driving in a manner that restores their original level of risk. It appears that a great many people support laws that compel them to be safer than they choose to be<ref>John Adams, [http://john-adams.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2006/risk,%20freedom%20&%20responsibility.pdf 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility'], Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, Inst. of US Studies, Senate House, 6 October ''1998, Published in The Risk of Freedom: individual liberty and the modern world'', Institute of United States Studies, 1999, p. 4.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Two points arise from this, firstly, irrespective of the validity of the claim that 'Statistics for death by accident and violence...display a stubborn resistance, over many decades, to the efforts of safety regulators to reduce them' it is clear that death by violence is not a particularly useful comparator variable to accidental deaths on the road. Secondly, a footnote to this section states 'Nowhere in the world is there evidence that seat belt laws have saved lives', citing his own research. This is patently not the case. With less cars on the roads there were an average of 8,700 deaths per year between 1939-1941 and the death rate on the roads has fallen fairly consistently since the 1970s with 7,700 deaths in 1972, around 6,000 in 1980, around 4,000 in 1990, just over 3,000 in 2000 and down to 1,754 in 2012<ref>Matthew Keep & Tom Rutherford, 'Reported Road Accident Statistics', Social and General Statistics Section, ''House of Commons Library'', 24 October 2013.</ref>. Although other factors will have contributed to the continuing reduction, it seems likely that the introduction of the law, and subsequent compliance with it, had at least a correlational relationship with the reduction in road deaths from 6,000 in 1980 to 4,000 by 1990, 7 years after the introduction of the law, which initially only required those in the front to wear a seatbelt<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/january/31/newsid_2505000/2505871.stm '1983: British drivers ordered to belt up'], ''BBC'', 31 January 1983, accessed 30 April 2015.</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Describing 'risks perceptible with the help of science' he notes: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%"> | ||

| + | Science has an impressive record in making invisible, or poorly understood, dangers perceptible, and in providing guidance about how to avoid them. Large decreases in premature mortality over the past 150 years, such as those shown for Britain in Figure 4, have been experienced throughout the developed world. Such trends suggest that ignorance is an important cause of death, and that science, in reducing ignorance has saved many lives<ref>John Adams, [http://john-adams.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2006/risk,%20freedom%20&%20responsibility.pdf 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility'], Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, Inst. of US Studies, Senate House, 6 October ''1998, Published in The Risk of Freedom: individual liberty and the modern world'', Institute of United States Studies, 1999, p. 5.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Yet he goes on to argue that using data from the past to estimate future risk can be problematic as knowledge of past risk can influence future risk, making it harder to 'objectively' manage risk. In addition, he argues that in an institutional setting a division of labour which separates risk management from the perceived rewards of risk serves to leave the 'pursuers disappointed and frustrated'<ref>John Adams, [http://john-adams.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2006/risk,%20freedom%20&%20responsibility.pdf 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility'], Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, Inst. of US Studies, Senate House, 6 October ''1998, Published in The Risk of Freedom: individual liberty and the modern world'', Institute of United States Studies, 1999, p. 7.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | He goes on to describe 'virtual risks' as risks 'beyond reliable knowledge' indicating his clear skepticism towards global warming and man made climate change. He states that virtual risk: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%"> | ||

| + | is the realm of culturally constructed risk. Virtual reality is a product of the | ||

| + | imagination which works upon the imagination. It is capable of simulating something real | ||

| + | - as in the case of a flight simulator used to train pilots - or something entirely imaginary | ||

| + | - as in the case of the Space Invaders of computer games. Virtual risks may, or may not, | ||

| + | be real - but they have real consequences<ref>John Adams, [http://john-adams.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2006/risk,%20freedom%20&%20responsibility.pdf 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility'], Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, Inst. of US Studies, Senate House, 6 October ''1998, Published in The Risk of Freedom: individual liberty and the modern world'', Institute of United States Studies, 1999, p. 8.</ref></blockquote>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Markets and Freedom=== | ||

| + | No documents relating to this lecture by [[Robert Summers]] currently found or subsequently reported in the [[Risk of Freedom Briefing]]. However, a report on the discussion may have appeared in ''Risk and Freedom'' (University of London Press, G. McDowell ed. 1999)<ref>See [http://library2.lawschool.cornell.edu/facbib/faculty.asp?facid=18 'Robert S Summers Books'], Cornell University Law Library, accessed 30 April 2015.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Markets and Morality=== | ||

| + | No documents relating to this lecture by [[Digby Anderson]] currently found or subsequently reported in the [[Risk of Freedom Briefing]]. However, an report on the conference notes 'Digby Anderson, of the free-market [[Social Affairs Unit]], declared that company boards had "only one moral obligation, and that is to those for whom they act"<ref>Melanie Phillips, 'The Tories are lost while they keep kicking nanny', ''The Sunday Times'', 11 October 1998.</ref>, demonstrating the tone of morality discussed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Funding== | ||

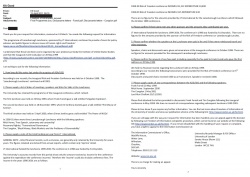

| + | [[File:Risk of freedom conference FOI.jpg|thumb|right|250px|''[[The Risk of Freedom conference]]'', sponsored by ''[[R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company]]'', 'Freedom of Information request for information on: the programme of Lanesborough Luncheons, sponsored by JT international', received 24 March 2011, returned 13 April 2011.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Risk of Freedom Conference was funded by R J Reynolds International. Information from an FOI request indicates that the conference received a total income of £31,327 and had an expenditure of £24,828 (1998-2000)<ref> University Records Manager & FOI Officer [[University of London]], 'Freedom of Information Request for information on: the programme of Lanesborough Luncheons, sponsored by JT international', received 24 March 2011, returned 13 April 2011.</ref>. These figures included only 'top line detail' and as such the 'income' could also have included funds accrued from conference fees<ref> University Records Manager & FOI Officer [[University of London]], 'Freedom of Information Request for information on: the programme of Lanesborough Luncheons, sponsored by JT international', received 24 March 2011, returned 13 April 2011.</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

==Speakers== | ==Speakers== | ||

| − | == | + | ===Kenneth Minogue=== |

| − | The Risk of Freedom | + | [[Kenneth Minogue]] was professor of Political Science at the London School of Economics (1984-1995), a director of the free market think tank the [[Centre for Policy Studies]] (1983-2009), and was chairman of the euro-sceptic: [[Bruges Group]] (1991-1993). Other affiliations included: [[Civitas]], the [[New Atlantic Initiative]], the [[Social Affairs Unit]] and the [[Taxpayers' Alliance]]. He also contributed articles to 2 [[Risk of Freedom Briefing]]s, the publication which reported the [[Lanesborough Luncheons]]. The first of these considered 'Freedom and Rights', taking the line that enshrining rights in law elevates the position of lawyers within society, and rights are only useful when a society has broken down. He also implies citizens of states who have long experienced a multidude of freedoms and rights are somehow superior to individuals who have been denied rights. He argues 'rights may well be valuable for people without experience of freedom, or perhaps whose freedoms had collapsed ...but (and it is a further paradox) their effect on us, who have long enjoyed a free constitution, is actually a very serious erosion of what we used to enjoy. For us, they are an encumbrance which undermines our sophisticated moral instincts and puts us at the mercy of casuists, bureaucrats and lawyers'. The latter simlarly considered legislation for diversity in the workplace in which he argued that 'diversity is the legislation of virtue, and like all such enterprises, it creates a parasitic class of compliance consultants, inspectors, regulators and tribunals to make the system work<ref>[http://powerbase.info/images/a/aa/The_Risk_of_Freedom_Briefing_-_issue_no_28_July_2006_%27Diversity%27.pdf 'Workplace diversity'], ''The Risk of Freedom briefing'', issue no. 28, July 2006, p. 3.</ref>. He also, somewhat ironically, argued that 'international organisations variations of culture mean that the ‘representatives’ of some countries are significantly more efficient and less corrupt than others', although the patronising tone of the piece suggests this is not an admission of his own corruptability<ref>[http://powerbase.info/images/a/aa/The_Risk_of_Freedom_Briefing_-_issue_no_28_July_2006_%27Diversity%27.pdf 'Workplace diversity'], ''The Risk of Freedom briefing'', issue no. 28, July 2006, p. 3.</ref>. |

| + | |||

| + | ===John Adams=== | ||

| + | [[John Adams]] is Emeritus Professor in the Geography department at [[University College London]]. According to his staff profile he was 'a member of the original Board of Directors of Friends of the Earth in the early 1970s' and has 'been involved in public debates about environmental issues ever since'<ref>[http://www.geog.ucl.ac.uk/about-the-department/people/emeritus/emeritus/john-adams/ 'John Adams Staff Profile'], University College London website, accessed 30 April 2015.</ref>. However, he now describes himself as a global warming 'agnostic'<ref>John Adams, [http://www.john-adams.co.uk/ 'Global Warming: a debate re-visited'], 25 June 2014,''John Adams Risk in a Hypermobile World'', accessed 30 April 2015.</ref>. Nevertheless, although he rejects the climate 'skeptic' label, the fact that he positions global warming under 'virtual risk' in his three type categorisation of risk types, demonstrates this would be a more appropriate description of his current standpoint<ref>[http://john-adams.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2006/risk,%20freedom%20&%20responsibility.pdf 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility'], Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, ''Inst. of US Studies'', Senate House, 6 October 1998</ref>. A review on his book ''Risk'' was published in the final [[Risk of Freedom Briefing]]<ref>[http://powerbase.info/images/a/a5/The_Risk_of_Freedom_Briefing_-_issue_no_32_July_2007_%27The_Theory_of_Risk%27.pdf The Risk of Freedom Briefing - Issue no 32, July 2007 'The Theory of Risk']</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Robert Summers==== | ||

| + | [[Robert Summers]] Summers is an expert in contracts law, commercial law, and jurisprudence and legal theory. According to his staff profile on the [[Cornell University]] website: 'he has written texts on legal realism, form and substance in the law, and on statutory interpretation. He has served as official advisor both to the Drafting Commission for Russian Civil Code and to the Drafting Commission for the Egyptian Civil Code, and he has lectured annually on jurisprudence and legal theory in Britain, Scandinavia, and Europe. Before retiring after a 42 year career at the Law School, Professor Summers taught contracts and American legal theory'<ref>See [http://www.lawschool.cornell.edu/faculty/bio.cfm?id=78 'Robert S Summers Professional Biography'], Cornell Law School, accessed 30 April 2015.</ref>. He appears to have represented a number of tobacco companies, including [[RJ Reynolds]] in a 'consolidated appeal of personal injury and wrongful death cases filed against various cigarette manufacturers, wholesalers, the [[Council for Tobacco Research]] - U.S.A., Inc., and the [[Tobacco Institute]]'<ref>[http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/unx36j00/pdf?search=%22no%20d%200948%22 'NO. D-0948 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS * * # PHILIP MORRIS INCORPORATED, ET AL. , Petitioners, VS. WELDON J, CARLISLE, ET AL.'], ''Legacy Tobacco Documents Library'', 21 June 1989, accessed 30 April 2015.</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Digby Anderson=== | ||

| + | [[Digby Anderson]] is a British right-wing intellectual, ordained priest and co-founder of the Thatcherite think-tank the [[Social Affairs Unit]], which has received funding from [[British American Tobacco]]. He was director of the Social Affairs Unit from its founding in 1980 until 2004. During that time he also worked as a newspaper columnist for [[The Times]] (1984-88), [[The Spectator]] (1984-2000), [[Sunday Telegraph]] (1988-89), [[Sunday Times]] (1989-90), and the [[National Review]] (1991-99). He also gave a speech entitled 'how to argue for advertising' for the Social Affairs Unit in 1995<ref>Digby Anderson, [http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/evp50d00/pdf?search=%22digby%20anderson%22 'How to Argue for Advertising'], An address given to the International Symposium "Advertising and the Media in an Open Society", presented by the national Review Institute and the IAA, May 1995, in New York City, ''Legacy Tobacco Documents Library'', accessed 30 April 2015.</ref> He also gave a lecture on 'Guilt, morality & pleasure' for the [[Associates for Research Into the Science of Enjoyment]] ([[ARISE]]), whose aim is 'To discuss the enjoyment and problems of guilt associated with everyday pleasures including alcoholic drinks, coffee, savoury snacks, sweet things such as biscuits cakes and chocolate, tea and tobacco'<ref>Professor David M. Warburton, 'Workshop on The value of pleasures : and the question of guilt', organised by ARISE, 20-23 April 1997,''Legacy Tobacco Documents Library'', accessed 30 April 2015.</ref>. Invitees to this event included [[John Robinson]] of [[RJ Reynolds]]. He also contributed an article to the subsequent [[Risk of Freedom Briefing]] discussing addiction where he wrote 'Those eager to over-use the word addiction and talk of addiction to gambling, sweets, sex and crisps are either silly or simply eager to expand their own antiaddiction industry and incomes'<ref>[http://powerbase.info/images/5/59/The_Risk_of_Freedom_Briefing_-_issue_no_13_Ocotber_2002_%27addiction%27.pdf The Risk of Freedom Briefing - Issue no 13, Ocotber 2002 'addiction'].</ref>. | ||

==Resources== | ==Resources== | ||

| + | *[https://www.legacy.library.ucsf.edu/ Legacy Tobacco Documents Library] | ||

| + | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

[[Category: Tobacco Industry]] | [[Category: Tobacco Industry]] | ||

Latest revision as of 16:28, 4 May 2015

The Risk of Freedom conference was organised by Roger Scruton for the Institute of United States Studies and sponsored by tobacco giant RJ Reynolds. The conference brought together a number of tobacco industry linked libertarian thinkers to present their views on the moral questions regarding freedom, risk, responsibility and markets. Speakers received £1,000 for their services whilst the chairs and discussants also received an honorarium of £300[1]. The conference led to the subsequent Lanesborough Luncheons and the Risk of Freedom Briefing's which reported on these events, although these were sponsored by Japan Tobacco International. The conference itself ran from Monday 5 October to Tuesday 6 October 1998 with a reception and dinner held on the Monday, followed by a full days conference on the Tuesday. The reception and dinner were held from 6pm at The Old Hall in Lincoln's Inn, which describes itself as 'an active and thriving society of lawyers with a very long history situated in a tranquil enclave of some 11 acres in central London. “Lincoln’s Inn” thus refers both to the Society and the place'[2]. Judge Robert H Bork from the American Enterprise Institute gave a keynote address.

Contents

Conference

The Conference was held on Tuesday 6 October 1998 at Beveridge Hall, University of London, Senate House, Malet Street, WC1E 7HU.

- The first session was entitled The Moral Foundations of Freedom. Janet Daley chaired the panel, which included Kenneth Minogue as the keynote speaker. They were joined by discussants David Selbourne and Noel Malcolm.

- The second session was entitled Responsibility and Risk and was chaired by Anthony Daniels. The rest of the panel consisted of keynote speaker John Adams and the discussants Frank Furedi and Perri 6.

- The third session was entitled Markets and Freedom and was chaired by Gary McDowell. The keynote speaker was Robert Summers who was joined by discussants John Wood and Tim Congdon.

- The final panel session was entitled Markets and Morality and was chaired by Roger Scruton. The keynote speaker was Digby Anderson who was joined by discussants Anthony Barnett and Baroness Mary Warnock.

The Moral Foundations of Freedom

The first lecture was given by Kenneth Minogue and covered by Minogue himself in The Independent. In this he described the economy as being 'at the heart of the softness of manners and abundance of material opportunities open to us in the modern world'. In addition he argued that only technological innovation had shielded this apparently compassionate economy from the despotic appropriation of its resources by the state. He also argues that societal efforts to tackle inequality in fact demonstrate an attack on freedom, and that the ideas of prejudice, racism and sexism should be presented as 'prejudice', 'racism' and 'sexism' as their existence required a fertile imagination:

The ground of the state's bid to control the economy was justice. Many thinkers argued that the gap between rich and poor was the great evil of human life. They demanded that the power of the state, whose legitimate point was to secure order for a free people, should now be directed to redistributing wealth. In time, the state began appropriating half of everything an economy produced, a level of rapacity that would have brought tears of admiration to the eyes of the most hardened oriental despot, and tolerable only because of the abundance created by technology....This development emerged from a new theory of the state. Liberal democracies, it was argued, were not civil associations of individuals free to pursue their own desires, but were, rather, a pattern of homogenous units, each with its own specific interests and demands. The clearest example of this theory was the so-called "multicultural" society, in which the units were ethnic groups, taken as "cultures" and constituting the political sub- communities of which the state was taken to be composed...It happened that not all these groups liked or approved of each other, a situation called "prejudice" or, in specific cases, "racism", "sexism", etc. Given a moral ideal of justice as the equal distribution of benefits, including equality between these newly discovered elements of society, the state discovered a duty to engineer a new, improved society exhibiting justice in this sense. Voluntary associations often did not mirror this new sociological composition of British society, and in the name of justice a social plan came down over British life like a mist. The aim was statistical homogeneity as exhibited in wealth, vocational engagement, incidence of prison sentences, health, and any other indicator that might occur to the fertile imaginations of excitable lobby groups speaking for blacks, browns, women, homosexuals, the disabled or any other element in the new plural society[3]

A report on the conference also noted:

Then there was Professor Kenneth Minogue. He declared the state had made us all slaves (what he would call the unfortunates who live under regimes which deny them democracy or human rights isn't clear), confiding en passant: "Everyone knows that women and ethnic employees are less competent than white males"[4]

Responsibility and risk

The second lecture topic was presented by John Adams a former member of Friends of the Earth turned climate 'agnostic'. The lecture frequently cited the Revolutionary Communist Party's former lead member Frank Furedi's work, and the work of the chair of the discussion Anthony Daniels. The lecture presented risk as being usefully distinguished by three categories, with global warming included in the 'virtual risk' section, which serves to describe risk on which scientists cannot agree:

- directly perceptible risks: e.g. climbing a tree, riding a bicycle, driving a car,

- risks perceptible with the help of science: e.g. cholera and other infectious diseases,

- virtual risks - scientists do not know or cannot agree: e.g. BSE/CJD, suspected carcinogens, global warming[5]

Describing 'directly perceptible risks' he argues that safety regulators fail to see the 'rewards' individuals attach to smoking, ignoring that any perceived reward is likely related to the addictive quality of smoking:

Why do so many people insist on taking more risks than safety authorities think they should? It is unlikely that they are unaware of the dangers - there can be few smokers who have not received the health warning. It is more likely that the safety authorities are less appreciative of the rewards of risk taking[6]

Adams also seeks to use the example of seat belts to argue that attempts to regulate directly perceptible risks are doomed to failure due to people's instinctive self-management of these risks and that perverse side-affects are caused by regulation. Without actually quoting any statistics he states that:

There is now abundant evidence, particularly with respect to directly perceived risks on the road, that risk compensation, sometimes referred to as offsetting behaviour, accompanies the introduction of safety measures. Statistics for death by accident and violence, perhaps the best available aggregate indicator of the way in which societies cope with directly perceived risk, display a stubborn resistance, over many decades, to the efforts of safety regulators to reduce them. With directly perceptible risks we encounter an intriguing ambivalence. In Britain both opinion poll evidence and a high level of compliance with the seat belt law suggest that this measure, which is designed to protect people from themselves, enjoys a high measure of popular support. And yet there is compelling evidence that motorists have responded to such measures by driving in a manner that restores their original level of risk. It appears that a great many people support laws that compel them to be safer than they choose to be[7]

Two points arise from this, firstly, irrespective of the validity of the claim that 'Statistics for death by accident and violence...display a stubborn resistance, over many decades, to the efforts of safety regulators to reduce them' it is clear that death by violence is not a particularly useful comparator variable to accidental deaths on the road. Secondly, a footnote to this section states 'Nowhere in the world is there evidence that seat belt laws have saved lives', citing his own research. This is patently not the case. With less cars on the roads there were an average of 8,700 deaths per year between 1939-1941 and the death rate on the roads has fallen fairly consistently since the 1970s with 7,700 deaths in 1972, around 6,000 in 1980, around 4,000 in 1990, just over 3,000 in 2000 and down to 1,754 in 2012[8]. Although other factors will have contributed to the continuing reduction, it seems likely that the introduction of the law, and subsequent compliance with it, had at least a correlational relationship with the reduction in road deaths from 6,000 in 1980 to 4,000 by 1990, 7 years after the introduction of the law, which initially only required those in the front to wear a seatbelt[9].

Describing 'risks perceptible with the help of science' he notes:

Science has an impressive record in making invisible, or poorly understood, dangers perceptible, and in providing guidance about how to avoid them. Large decreases in premature mortality over the past 150 years, such as those shown for Britain in Figure 4, have been experienced throughout the developed world. Such trends suggest that ignorance is an important cause of death, and that science, in reducing ignorance has saved many lives[10]

Yet he goes on to argue that using data from the past to estimate future risk can be problematic as knowledge of past risk can influence future risk, making it harder to 'objectively' manage risk. In addition, he argues that in an institutional setting a division of labour which separates risk management from the perceived rewards of risk serves to leave the 'pursuers disappointed and frustrated'[11]

He goes on to describe 'virtual risks' as risks 'beyond reliable knowledge' indicating his clear skepticism towards global warming and man made climate change. He states that virtual risk:

is the realm of culturally constructed risk. Virtual reality is a product of the imagination which works upon the imagination. It is capable of simulating something real - as in the case of a flight simulator used to train pilots - or something entirely imaginary - as in the case of the Space Invaders of computer games. Virtual risks may, or may not,

be real - but they have real consequences[12]

.

Markets and Freedom

No documents relating to this lecture by Robert Summers currently found or subsequently reported in the Risk of Freedom Briefing. However, a report on the discussion may have appeared in Risk and Freedom (University of London Press, G. McDowell ed. 1999)[13]

Markets and Morality

No documents relating to this lecture by Digby Anderson currently found or subsequently reported in the Risk of Freedom Briefing. However, an report on the conference notes 'Digby Anderson, of the free-market Social Affairs Unit, declared that company boards had "only one moral obligation, and that is to those for whom they act"[14], demonstrating the tone of morality discussed.

Funding

The Risk of Freedom Conference was funded by R J Reynolds International. Information from an FOI request indicates that the conference received a total income of £31,327 and had an expenditure of £24,828 (1998-2000)[15]. These figures included only 'top line detail' and as such the 'income' could also have included funds accrued from conference fees[16].

Speakers

Kenneth Minogue

Kenneth Minogue was professor of Political Science at the London School of Economics (1984-1995), a director of the free market think tank the Centre for Policy Studies (1983-2009), and was chairman of the euro-sceptic: Bruges Group (1991-1993). Other affiliations included: Civitas, the New Atlantic Initiative, the Social Affairs Unit and the Taxpayers' Alliance. He also contributed articles to 2 Risk of Freedom Briefings, the publication which reported the Lanesborough Luncheons. The first of these considered 'Freedom and Rights', taking the line that enshrining rights in law elevates the position of lawyers within society, and rights are only useful when a society has broken down. He also implies citizens of states who have long experienced a multidude of freedoms and rights are somehow superior to individuals who have been denied rights. He argues 'rights may well be valuable for people without experience of freedom, or perhaps whose freedoms had collapsed ...but (and it is a further paradox) their effect on us, who have long enjoyed a free constitution, is actually a very serious erosion of what we used to enjoy. For us, they are an encumbrance which undermines our sophisticated moral instincts and puts us at the mercy of casuists, bureaucrats and lawyers'. The latter simlarly considered legislation for diversity in the workplace in which he argued that 'diversity is the legislation of virtue, and like all such enterprises, it creates a parasitic class of compliance consultants, inspectors, regulators and tribunals to make the system work[17]. He also, somewhat ironically, argued that 'international organisations variations of culture mean that the ‘representatives’ of some countries are significantly more efficient and less corrupt than others', although the patronising tone of the piece suggests this is not an admission of his own corruptability[18].

John Adams

John Adams is Emeritus Professor in the Geography department at University College London. According to his staff profile he was 'a member of the original Board of Directors of Friends of the Earth in the early 1970s' and has 'been involved in public debates about environmental issues ever since'[19]. However, he now describes himself as a global warming 'agnostic'[20]. Nevertheless, although he rejects the climate 'skeptic' label, the fact that he positions global warming under 'virtual risk' in his three type categorisation of risk types, demonstrates this would be a more appropriate description of his current standpoint[21]. A review on his book Risk was published in the final Risk of Freedom Briefing[22].

Robert Summers

Robert Summers Summers is an expert in contracts law, commercial law, and jurisprudence and legal theory. According to his staff profile on the Cornell University website: 'he has written texts on legal realism, form and substance in the law, and on statutory interpretation. He has served as official advisor both to the Drafting Commission for Russian Civil Code and to the Drafting Commission for the Egyptian Civil Code, and he has lectured annually on jurisprudence and legal theory in Britain, Scandinavia, and Europe. Before retiring after a 42 year career at the Law School, Professor Summers taught contracts and American legal theory'[23]. He appears to have represented a number of tobacco companies, including RJ Reynolds in a 'consolidated appeal of personal injury and wrongful death cases filed against various cigarette manufacturers, wholesalers, the Council for Tobacco Research - U.S.A., Inc., and the Tobacco Institute'[24].

Digby Anderson

Digby Anderson is a British right-wing intellectual, ordained priest and co-founder of the Thatcherite think-tank the Social Affairs Unit, which has received funding from British American Tobacco. He was director of the Social Affairs Unit from its founding in 1980 until 2004. During that time he also worked as a newspaper columnist for The Times (1984-88), The Spectator (1984-2000), Sunday Telegraph (1988-89), Sunday Times (1989-90), and the National Review (1991-99). He also gave a speech entitled 'how to argue for advertising' for the Social Affairs Unit in 1995[25] He also gave a lecture on 'Guilt, morality & pleasure' for the Associates for Research Into the Science of Enjoyment (ARISE), whose aim is 'To discuss the enjoyment and problems of guilt associated with everyday pleasures including alcoholic drinks, coffee, savoury snacks, sweet things such as biscuits cakes and chocolate, tea and tobacco'[26]. Invitees to this event included John Robinson of RJ Reynolds. He also contributed an article to the subsequent Risk of Freedom Briefing discussing addiction where he wrote 'Those eager to over-use the word addiction and talk of addiction to gambling, sweets, sex and crisps are either silly or simply eager to expand their own antiaddiction industry and incomes'[27].

Resources

Notes

- ↑ University Records Manager & FOI Officer University of London, 'Freedom of Information Request for information on: the programme of Lanesborough Luncheons, sponsored by JT international', received 24 March 2011, returned 13 April 2011.

- ↑ 'The Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn', accessed 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Kenneth Minnogue, 'Podium: The nationalisation of society', The Independent, 9 October 1998.

- ↑ Melanie Phillips, 'The Tories are lost while they keep kicking nanny', The Sunday Times, 11 October 1998.

- ↑ John Adams, 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility', Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, Inst. of US Studies, Senate House, 6 October 1998, Published in The Risk of Freedom: individual liberty and the modern world, Institute of United States Studies, 1999, p. 3.

- ↑ John Adams, 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility', Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, Inst. of US Studies, Senate House, 6 October 1998, Published in The Risk of Freedom: individual liberty and the modern world, Institute of United States Studies, 1999, p. 4.

- ↑ John Adams, 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility', Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, Inst. of US Studies, Senate House, 6 October 1998, Published in The Risk of Freedom: individual liberty and the modern world, Institute of United States Studies, 1999, p. 4.

- ↑ Matthew Keep & Tom Rutherford, 'Reported Road Accident Statistics', Social and General Statistics Section, House of Commons Library, 24 October 2013.

- ↑ '1983: British drivers ordered to belt up', BBC, 31 January 1983, accessed 30 April 2015.

- ↑ John Adams, 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility', Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, Inst. of US Studies, Senate House, 6 October 1998, Published in The Risk of Freedom: individual liberty and the modern world, Institute of United States Studies, 1999, p. 5.

- ↑ John Adams, 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility', Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, Inst. of US Studies, Senate House, 6 October 1998, Published in The Risk of Freedom: individual liberty and the modern world, Institute of United States Studies, 1999, p. 7.

- ↑ John Adams, 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility', Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, Inst. of US Studies, Senate House, 6 October 1998, Published in The Risk of Freedom: individual liberty and the modern world, Institute of United States Studies, 1999, p. 8.

- ↑ See 'Robert S Summers Books', Cornell University Law Library, accessed 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Melanie Phillips, 'The Tories are lost while they keep kicking nanny', The Sunday Times, 11 October 1998.

- ↑ University Records Manager & FOI Officer University of London, 'Freedom of Information Request for information on: the programme of Lanesborough Luncheons, sponsored by JT international', received 24 March 2011, returned 13 April 2011.

- ↑ University Records Manager & FOI Officer University of London, 'Freedom of Information Request for information on: the programme of Lanesborough Luncheons, sponsored by JT international', received 24 March 2011, returned 13 April 2011.

- ↑ 'Workplace diversity', The Risk of Freedom briefing, issue no. 28, July 2006, p. 3.

- ↑ 'Workplace diversity', The Risk of Freedom briefing, issue no. 28, July 2006, p. 3.

- ↑ 'John Adams Staff Profile', University College London website, accessed 30 April 2015.

- ↑ John Adams, 'Global Warming: a debate re-visited', 25 June 2014,John Adams Risk in a Hypermobile World, accessed 30 April 2015.

- ↑ 'Risk, Freedom and Responsibility', Paper for conference on The risk of Freedom, Inst. of US Studies, Senate House, 6 October 1998

- ↑ The Risk of Freedom Briefing - Issue no 32, July 2007 'The Theory of Risk'

- ↑ See 'Robert S Summers Professional Biography', Cornell Law School, accessed 30 April 2015.

- ↑ 'NO. D-0948 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS * * # PHILIP MORRIS INCORPORATED, ET AL. , Petitioners, VS. WELDON J, CARLISLE, ET AL.', Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, 21 June 1989, accessed 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Digby Anderson, 'How to Argue for Advertising', An address given to the International Symposium "Advertising and the Media in an Open Society", presented by the national Review Institute and the IAA, May 1995, in New York City, Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, accessed 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Professor David M. Warburton, 'Workshop on The value of pleasures : and the question of guilt', organised by ARISE, 20-23 April 1997,Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, accessed 30 April 2015.

- ↑ The Risk of Freedom Briefing - Issue no 13, Ocotber 2002 'addiction'.