National Special Branch Intelligence System

This article is part of the Undercover Research Portal at PowerBase - investigating corporate and police spying on activists.

The National Special Branch Intelligence System or NSBIS was database software used by Special Branch and Counter Terrorism units by British police forces. It is also referred to as the National Special Branch Information System. It was introduced around 2003, but has since been since superseded by the National Common Intelligence Application.[1]

It is formally defined as:[1]

- Information management system used to host information and intelligence gathered in the course of counter-terrorism investigations.

Rather than being a single database, it was a software which ran on local police services to serve individual units, known as 'instances'. However, NSBIS appears to have incorporated connectivity between the different instances, particularly with one known as NSBIS-N (see below).

According to a 2020 IOPC report:[2]

- 316.. NSBIS is designed to computerise the functions carried out by Special Branch Groups, Nationality (OVRO), Ports and Special Branch offices. The data is held in a single database with access rights limited only to specified groups of officers for specific reasons. One of these groups of officers was the [National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit (NDEDIU)]. Intelligence related to domestic extremist activity, sourced from police forces, counter-terrorism units, industry and open sources, was shared through, organized and recorded on NSBIS.

NSBIS was distinct from other systems such as the Police National Computer and the Police National Database and could not be accessed through them.[1] This was so it could store classified and other protectively marked material, marked up to level of 'Secret', which other Metropolitan Police databases were unsuitable for storing.[3][4]

Individual Special Branch / Counter Terrorism units were able to customise aspects of it. This lead to 'inconsistent and varied information-recording practices', a weakness which lead to the development of its successor, the National Common Intelligence Application.[1]

Once the process of transferring to the NCIA has been done, the NSBIS databases will be marked as 'Legacy' databases. Due to their relevance to the Undercover Policing Inquiry, they will not be disposed of in line with normal police Review, Retention and Deletion policy. Any access / ownership will still go through the host organisations rather than the Inquiry.[5]

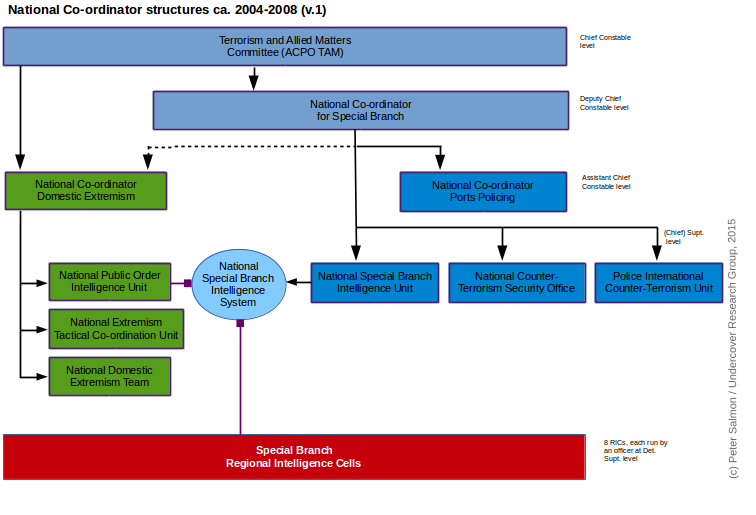

In the 2000s, NSBIS came under the aegis of the National Coordinator for Special Branch,[6] a role managed by the ACPO Terrorism & Allied Matters Committee.

Contents

Origins

NSBIS appears to have begun as a information management strategy that turned into a computer system incorporating a database developed under the aegis of the Association of Chief Police Officer's Terrorism and Allied Matters Committee.

NSBIS was originally a set of 'national standards for the management of intelligence by the individual special branches'.[7]

An earlier incarnation of the system was developed and deployed by private contractor Serco in the 1990s.[8][5]

NSBIS 2 was developed by Serco Project Engineering, with work starting as early as 1999, for which held contracts to run support services from 2002 to 2012[9][10][11]

A key moment was HM Inspectorate of Constabularly's (HMIC) 2003 thematic inspection of Special Branch units, A Need to Know. HMIC noted that Special Branch lacked adequate IT and that 'overall, a Special Branch national IT network would significantly enhance effectiveness, stating:[12]

- HMIC identified a high priority requirement for a national Special Branch IT programme with commensurate IT development leading to the establishment of a national Special Branch IT network with sufficient terminals in all SB offices and major ports. HMIC is aware and fully supportive of current development work on the second generation National Special Branch Intelligence System (NSBIS2) but also concerned that running costs are likely to inhibit the establishment of a national Special Branch network. ACPO (TAM) has, through the National Special Branch Technology Unit (NSBTU), been developing a National Special Branch Information Management Strategy. [...]

The same report found:

- However the inadequacy of current arrangements cannot be overstated and the development of a national IT strategy for Special Branch and Ports Policing is long overdue. ACPO (TAM) is actively developing IT systems to provide this national network and HMIC encourages all forces to work closely with them in aligning their long term procurement program.

and HMIC recommended:

- ... as a matter of priority the Home Office enables identified national Special Branch IT requirements to be implemented and most importantly funded, through a clear, robust, time-tabled strategy.

As of September 2004 work in relation to it was ongoing Parliament was told that work on NSBIS was ongoing.[13]

Screenshots from NSBIS Review Retention and Deletion manual[6]

Particular instances

A number of individual forces have confirmed by 2011 they were using NSBIS software including Metropolitan Police,[11] Hampshire[14] and Avon & Somerset.[15]

National police units which also used it were the National Ports Analysis Centre, National Ports Unit,[5] National Ballistic Intelligence Service (NABIS) and the Penalty Notice Processing unit (PentiP[16]).[17]

It appears that UK Border Agency used it as well.[10]

NSBIS-N

There was a national installation referred to as NSBIS-N or 'National NSBIS', which[5][11]

NSBIS-N only became operational in April 2008, prior to which there was no national installation.[5] Once it became live, however:[18]

- When forces input information onto their local NSBIS, this was automatically uploaded to NSBIS-N. While there was an option to prevent this from happening, basic details associated with an entry such as names, addresses and telephone numbers would still be uploaded to NSBIS-N.

This was alternatively noted as:[5]

- ... each force or unit installation of NSBIS will include an individual store of data which is not replicated on any other installation of NSBIS save to the extent that

- 1) Limited information providing a trace of each entry will appear on the NSBIS, provided the default option to do so has not been changed by a local force or unit; and

- 2) Individual forces or units chose to transfer information to another force or unit via secure email transfer, and that second force or unit takes the decision to upload it to their installation upon receipt.

- ... each force or unit installation of NSBIS will include an individual store of data which is not replicated on any other installation of NSBIS save to the extent that

NSBIS-N wass under the control of the National Counter Terrorism Policing Headquarters.[5] NCTPHQ is a successor unit to the ACPO Terrorism and Allied Matters Committee, playing a national lead on counter terrorism and domestic extremism policing. SOURCES.

Curiously, the Metropolitan Police had search access to NSBIS-N, while neither NCTPOC or the Police Service of Northern Ireland had any access.[5]

It appears that some local Special Branch units migrated to the national NSBIS, for example, Gloucestershire and Devon & Cornwall forces, a 2012 document stating:[19]

- SB in both Glos and D&C will migrate to the national SB intelligence system (NSBIS) during March 2013, ensuring all forces in the region utilise the same IT system and lay the foundation for regional secure IT connectivity.

NCTPOC / CTPNOC NSBIS

This instance of NSBIS is used by the National Counter Terrorism Policing Operations Command (NCTPOC) - now named the Counter Terrorism Policing National Operational Command (CTPNOC).[20] Though CTPNOC is hosted by the Metropolitan Police, the CTPNOC NBSIS is located on different servers and operates independently of SO15 NBSIS.[20]

According to a statement of Michael Killeen, head of intelligence for CTPNOC:[21]

- 102. ... NCTPOC uses guidance provided by the College of Policing in the national standards of Intelligence Management and MoPI to guide whether to input information, and in what format, onto NSBIS.

- 103. NCTPOC staff members are expected to work in accordance with the principles of Intelligence Management as a whole but paragraph 2.3 of the Intelligence report section of Intelligence Management states:

- OFFICIAL Information content ... Information should be for a policing purpose. It should be clear, concise and without abbreviations. The information must be of value and understood without the need to refer to other information sources. The body of the report should give no indication of the nature of the source, whether human or technical, or the proximity of the source to the information.

- 104. Information recorded on NSBIS is expected to comply with these requirements.

SO15 NSBIS

In late 2011, Counter Terorism Command (SO15), within the Metropolitan Police, adopted its own version of NSBIS, held within the Intelligence Management and Operation Support unit. There it interfaces with legacy systems used for the digitising of the indices for the old Special Branch Registry.[20]

A 2015 SO15 briefing wrote:[22]

- This system contains all intelligence reports received into the London Intelligence Unit since December 2011 when NSBIS was adopted. When the system is interrogated to establish how many reports it contains the database is so large the document search fails - 4,000 reports were added in July 2014 and we've had the system since December 2011. In addition all the data from the preceding BRS is also stored in the database. Analysis of audit figures gives a best guess suggesting there are approximately 800,000 identifiable records.

Domestic Extremism

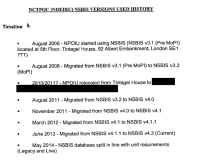

The history of the national domestic extremism units is convoluted one and is covered in a separate article. An early unit, the National Public Order Intelligence Unit, created an instance of NSBIS in August 2006.SOURCE: HMIC 2012 & 2013[21][23] This became what is generally referred to as the National Domestic Extremism Database]].

When the national domestic extremism units passed to control of the Metropolitan Police in 2011, the database was continued, the controlling unit renamed National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit (NDEDIU) and subsequent renamings / re-structurings.[21] [24]NDEDIU has since been submerged into CTPNOC,[20] though the function has remained.

In May 2014, NDEDIU (as it still was) initiated a new instance of NSBIS. This was because the list of records marked for review in light of HM Inspectorate of Constabulary investigations critical of the large volume of material being retained,[18] had become so large it caused the system to lock and ceased functioning properly. As a result a new database was started, and the 2006 database began being referred to as the Legacy database. [21][18]

For the 2014 database, the NDEDIU manually migrated over records over from the 2006 Legacy database. These records were chosen in light of relevant Metropolitan Police policies on information Review, Retention and Deletion (RRD). The Legacy database can still be accessed for certain purposes, including the Undercover Policing Inquiry.[21]

The new NSBIS database 'contains material relating to domestic extremism and strategic public order'. This includes intelligence reports and nominals.[21]

According to one report:[18]

- On local installations of NSBIS, there was an option for forces to pass information uploaded directly to NDEDIU's installation of NSBIS, if they considered it relevant to the NDEDIU's role of assessing intelligence relating to domestic extremism.

'Fairway'

Various references to a national Fairway database can be found.

In 2008, Fairway was a Joint Terrorism Analysis Centre project which:[25]

- produces a variety of reports tailored to meet the needs of individual customer departments. These are sanitised intelligence reports that are disseminated to a wide range of Police customers via Special Branches. They are predominantly intended for use as background briefing documents among officers and staff engaged in operations duties, in order to heighten awareness of the current international terrorist threat.1012

Fairway has been referred to as 'the umbrella title given to various work streams which feed into an intelligence database designed to counter terrorism in its earliest stages of planning', and:[26]

- The programme asks police officers and security personnel to be aware of the constant threat of terrorism and feed any gathered intelligence, including any concerns regarding individuals behaviour, to their local Special Branch for inclusion on to the National Fairway database.

The Fairway database was also used to record details of journalists and photographers, linking it to the National Domestic Extremism Database.[27] Given the national remit of Fairway, it would appear the database it fed into is likely the National NSBIS above.

Resources

Related articles

- National Domestic Extremism Database.

- National Domestic Extremism Unit

- National Common Intelligence Application

- Special Branch Registry

External documents

- Witness statement of Det. Insp. Alistair Pocock, 2017 (via ucpi.org.uk)

- NSBIS Review, Retention and Disposal Guide, 2008 (via ucpi.org.uk)

- NBSIS Weeding Overview, undated (via ucpi.org.uk)[28]

- Business case for new NDEDIU NSBIS instance, 25 October 2013 (via ucpi.org.uk)

- ACPO TAM Intelligence Systems Services - ISS Pre Transformation Visit to NDEDIU, Monday 24th March to Friday 28th March 2014 v1.1 (via ucpi.org.uk)

- NDEDIU Nominal Creation Policy, 2013 (via Netpol.org)

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Building the Picture: An inspection of police information management, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, July 2015 (accessed 1 June 2020).

- ↑ Darren Walton, Operation Gilbert: Investigation into allegations that members of the National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit (NDEDIU) illegally accessed the email accounts of environmental campaigners and sympathetic journalists, Independent Office for Police Conduct, 8 November 2019 (accessed 1 June 2020).

- ↑ Either to Government Protective Marking Scheme or its successor protocol, the Government Security Classification Policy.

- ↑ Mick Creedon, Report 3 - Special Demonstration Squad Reporting: Mentions of Sensitive Campaigns, Operation Herne / Metropolitan Police, July 2014 (accessed 1 June 2020).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Jeffery Lamprey, Witness statement, National Counter Terrorism Policing Headquarters / Metropolitan Police, 19 December 2016 (accessed 2 June 2020 via ucpi.org.uk).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 NSBIS Review, Retention and Disposal Guide, Serco Project Engineering, 2008 (via ucpi.org.uk as exhibit to the witness statement of Alistair Pocock),

- ↑ CC. Paddy Tomkins, Examination of Witnesses (Questions 40-59) Assistant Commissioner David Veness and Chief Constable Paddy Tomkins, Committee on European Union (House of Lords), 27 October 2004 (accessed 7 June 2020 via Parliament.uk).

- ↑ Andrew Hubbard, Profile, LinkedIn.com, undated (accessed 2 June 2020).

- ↑ Contacts to be published externally, Sussex Police, 16 March 2012 (accessed 1 June 2020 via WhatDoTheyKnow.com).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Mehar Chauhan, Profile, LinkedIn.com, undated (accessed 1 June 2020).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Mention of an NSBIS-N related contract occurs for the financial year 2010-2011. See Appendix AC_15.pdf, London.gov.uk, 3 March 2016. However, a 2016 Metropolitan police document notes that the NBSIS-N migration had not started at that point. See All projects on the DP Portfolio register were reviewed against the agreed set of critera - Appendix T 15, Metropolitan Police, document created 23 March 2016.

- ↑ David Blakey, A Need To Know: HMIC Thematic Inspection of Special Branch and Ports Policing, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, January 2003 (accessed 7 June 2020).

- ↑ CC William Rae, Memorandum by Association of Chief Police Officers, Scotland (ACPOS), Select Committee on European Union (House of Lords), 9 September 2004 (accessed 1 June 2020).

- ↑ Disclosure Log - Jan 2012 - March 2012, Hampshire Police, 1 November 2012 (accessed 1 June 2020).

- ↑ FOIA request response: IT applications used, Avon & Somerset Police, 18 April 2012 (accessed 1 June 2012).

- ↑ Tom McNulty, PentiP System: Home Department written questions, 24 January 2007 (accessed 7 June 2020 via TheyWorkForYou.com).

- ↑ Ian Stainer, Enhancing Intelligence-Led Policing: Law Enforcement' Big Data Revolution', in Big Dat Challenges: Society, Security, Innovation and Ethics, ed. Anno Bunnik, Anthony Cawley, Michael Mulqueen & Andrej Zwitter, Springer, 2016.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Edward Parsons, Baroness Jenny Jones: Investigation into the deletion of material relating to Baroness Jenny Jones and/or the Undercover Policing Inquiry, Independent Office for Police Conduct, 14 February 2019 (accessed 1 June 2020).

- ↑ Report of the Chief Constable - Strategic Alliances, Avon and Somerset Police Authority, 28 March 2012 (accessed via Archive.org).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Det. Insp. Alistair Pocock, Witness statement, Metropolitan Police Service, 6 April 2017, incorporating statement of 3 January 2017 (accessed via Undercover Policing Inquiry - ucpi.org.uk).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 Det. Supt. Michael Killeen, Witness statement, Metropolitan Police Service, 1 January 2017 - incorporating statements of 22 June 2016 and extension of 20 September 2016 (accessed via Undercover Policing Inquiry - ucpi.org.tuk).

- ↑ Appendix A to SO15 report dated 11th June 2015 concerning Information Risks in SO15. Appears in Exhibit D754: Debriefing re Management of Information within SO15, Metropolitan Police, June 2015, (accessed via ucpi.org.uk, appended to a witness statement of Det. Supt. Neil Huchison).

- ↑ NCTPOC (NDEDIU) NSBIS versions used history, NCTPOC / Metropolitan Police, undated (accessed via ucpi.org.uk where it is an exhibit to the statement of Jeffrey Lamprey).

- ↑ A review of progress made against the recommendations in HMIC’s 2012 report on the national police units which provide intelligence on criminality associated with protest, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, June 2013 (accessed 1 June 2020).

- ↑ Ch. Insp. Geoff Bishop, Section 44 Terrorism Act 2000: Standard Operation Procedures, Metropolitan Police, 7 February 2008 (archived by Statewatch.org).

- ↑ Logistics security scrutinised at DHL & Reliance conference, Logistics Handling (trade newsletter), 28 June 2010 (accessed 1 June 2020).

- ↑ Jules Mattsson, Journalists named on secret files, police admit, The Times, 11 November 2014 (accessed 2 June 2020).

- ↑ Post June 2012, when NSBIS was upgraded to version 4.2. See NCTPOC (NDEDIU NSBIS Versions Used History, NCTPOC / Metropolitan Police, undated (accessed via ucpi.org.uk where it is an exhibit to the witness statement of Jeffrey Lamprey).