Dave Robertson (alias)

This article is part of the Undercover Research Portal at Powerbase - investigating corporate and police spying on activists

++Last updated July 2018++

David Robertson is the alias of a Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) undercover police officer. He is also referred to as HN45, the cypher given to him by Operation Herne. Details for him were released by the Undercover Policing Inquiry on 17 April 2018, saying he had infiltrated the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign and Banner Books from 1970 to 1973.[1] He had also held an administrative role in the unit 1982-83, which involved collation and internal distribution of intelligence reports, but 'not the tasking of undercover officers or target group selection.'[2]

According to an document from the Undercover Policing Inquiry:[3]

- HN45 returned to the SDS in the 1980s in an administrative role for about 3 years. In this role, he attended safe houses and collected diaries from deployed UCOs. He would also sanitise intelligence reports ready for circulation to wider parts of the police.

The Inquiry has ruled his real name cannot be revealed.[2]

Contents

Overview

Though only confirmed as an SDS undercover by the Undercover Policing Inquiry in 2018, Dave Robertson had been outed as a police officer in an earlier political memoir by the author Diane Langford. In her account, set out below, he was recognised as a Special Branch officer at a meeting around Indochina by a work colleague she had brought along, called Ethel. Robertson threatened Ethel's family in Ireland, but vanished from the group shortly afterwards. As well the inappropriateness of this behaviour, this account allows us to place him as active in the Maoist groups around Abhimanyu Manchanda who lead the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League.

According to the Undercover Policing Inquiry, Robertson had targeted the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign and Banner Books. The latter has been identified as an independent, un-alligned Maoist bookshop based in Camden, which served as a focal point for activists in the north London Maoist milieu as well as acting as an important international hub.

Robertson's connections to the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign are somewhat more problematic and less clear, partly because it belonged to a different and distinct political tradition in the Trotskyist milieu. Through analysis of the account of Ethel being threatened, it has been possible identify a way it may have happened. However, much more understanding is needed there.

Abhimanyu Manchanda and the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League

Abhimanyu Manchanda was a leading Maoist organiser in the late 1960s. In 1956 he had been General Secretary for the Indian Workers Association in London and member of Communist Party of Britain.[4] In 1965 he was suspended by The Communist Party, but left entirely. This was at a time when others of a more Maoist persuasion were also leaving to set up their own organisations - including Reg Birch (of whom more below).[5] Closely associated with Claudia Jones, Manchanda took over from her as editor of the West Indian Gazette.[6]

However, Manchanda also ploughed his own particular furlough. In 1966 he walked out of the founding conference of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign and set up the British Vietnam Solidarity Front, a smaller player in the protests of 1968, but far from insignificant.[7]

In the mid 1966s, Manchanda was active in various political groups such as the British Marxist-Leninist Organisation (along with Reg Birch) and the Joint Council of Communists, particularly as a representative of Association of Indian Communists (itself home to many leading Maoists and intertwined with the Indian Workers Association).[6][8] Manchanda and Birch parted ways in early 1968,[9] with Birch going on to set up the Communist Party of Britain (Marxist-Leninist), based not far from Manchanda in Fortress Road.

In 1968, fed by radical student politics, particularly the London branch of the Revolutionary Socialist Students' Federation,[10] Manchanda established the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League (RMLL) out of his home at Lisburn Road, NW3. The RMLL was a small group that worked through front groups such as the Friends of China (founded 1967) or British Vietnam Solidarity Front. In the 1968 protests, the Maoists were among those who argued against solely A to B type marches, and instead focused on demonstrating at the US Embassy in Grosvenor Square, which inevitably led to clashes with police.[8][11] Special Branch files from that year also focus on the role of Maoists in the disturbances, indicating they were considered of particular interest to the police.[7]

The RMLL suffered a number of splits throughout 1969 to 1971, after which it ceased as an effective organisation in its own name.[6][12] Nevertheless, it continued as a group of committed campaigners based in or near the London borough of Camden, continuing to work through front groups.

It is not yet know at what point that Dave Robertson entered the circles around the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League. From Diane Langford's writing it is clear he was active in it, even if he was under suspicion as an undercover in any case.

In the early 1970s, Manchanda remained focused on Vietnam and China.[13] Diane Langford notes the group was not open but membership acquired one of the RMLL's front groups such as the Friends of China, the British Vietnam Solidarity Front[14], the Women's Liberation Front, or the Solidarity Front of Arab and Palestine Liberation.[15] Thus it is very likely Robertson would have become involved through one of these front groups. Through them, particularly with the increasing focus on Indochina affairs, he would have had access to the wider organising networks, in particular, the other named target of his - the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC).

Vietnam Solidarity Campaign

Dominated by the International Marxist Group (IMG) since it's inception in 1966, the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign reached a high point in the protests in 1968. In 1969, the loose coalition of Trotskyist groups that formed it's core membership disintegrated and its activities went into decline, though it continued to maintain a presence through the Vietnam Solidarity Bulletin (renamed Indochina in 1970).

Through out the 1960s the relationship between the Maoists and the VSC had been rocky. Manchanda in particular had staged a walk out in 1966 to for the alternative British Vietnam Solidarity Front, and though there was involvement in ad hoc committees, there was various differences between the two sets of politics.[16] As such, the VSC as a group would have been separate from the milieu that Robertson was infiltrating, and so would seem he would have had relatively few opportunities to target it.

Nevertheless, the bombings of Cambodia by the United States, gave renewed interest in south east Asian issues and campaigners began to come together on the issue once more. Once such particular move was the 1972-1973 initiative, the Indochina Solidarity Committee - in many ways an off-shoot of the VSC, for instance, they shared a key organiser in the IMG's Pat Jordan, but one which Manchanda came on board with. It is likely that this is the point of contact for Robertson for spying on the VSC, particularly through the then newly forming Indochina Solidarity Committee.

This is probably the grounds that the Undercover Policing Inquiry has released that the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign had been a target of Dave Robertson. However, unless there are other activities by the undercover still to be revealed, the evidence found to date seems to indicate that it was not his primary target and the Inquiry is being opaque in this.

Overlap with other undercovers

It is notable that a number of the venues frequented by the RMLL, such as the Laurel Tree and The Enterprise Pubs, as well as the Camden Studios, were also frequented in 1969 by another SDS undercover officer John Graham when he was infiltrating another Maoist influenced group, the Camden Vietnam Solidarity Campaign.[17] According to the Undercover Policing Inquiry Graham also reported back on the Revolutionary Socialist Students' Federation.[18]

A third SDS undercover, using the name 'Alex Sloan', targeted one of the groups that split from the RMLL: the Communist Workers League of Britain, which was behind the Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front and also active in and and around Camden. Like Robertson, 'Alex Sloan' was deployed 1971 to 1973.

A fourth undercover infiltrated the Women's Liberation Front, set up by Diane Langford, when in the early 1970s the RMLL developed a focus on feminist issues and the growing women's liberation movement. The address for the new group was house on Lisburn Road[19] which Diane shared with Manchanda and served as an effective headquarters for the RMLL and its associated groups. In 1972-1973 the Women's Liberation Front was targeted by female SDS undercover, known only as 'Sandra' (HN348).[20]

Banner books

Banner Books and Crafts Ltd[21] was an independent radical bookshop based at 90 Camden High Street, London, NW1. It was founded in 1971 by the Indian Maoist G. V. Bijur. Bijur had previously been arrested for selling Mao Tse-tung's 'Little Red Book' at Speakers Corner. He continued to sell it at his shop, where he also had female staff dressed as 'Young Pioneers', and a bust of Mao on display in the window.[22][23][24]

The bookshop focused on material from China and groups that were Maoist in nature, though also sold other material from anti-racist and progressive groups[25] such as Peace News.[26] The shop was destroyed in a fire in 1975 (apparently started by the National Front[25]). Bijur, having been injured in the fire, returned to India where he used the insurance money to set up another bookshop in New Delhi.[23][27]

Unlike many other such bookshops it does not appear to have aligned itself with one particular group, though it was 'an unofficial clearing house and contact for activists'.[22] One source noted it's importance as a hub:[28]

- In the early 1970s, Bijur provided "a supply source and meeting place for revolutionaries from every continent. Irish republicans in Long Kesh were among the many who ordered stacks of book by post. Third World leaders passing through London, often dossed down on the floor of Banner Books."

This is the sort of information Special Branch would have been interested in.

That Banner Books held an important place in the Maoist milieu of north London readily seen. The shop was one of three Maoist aligned bookshops in London in the early to mid 1970s. Nearby in north London was Bellman Books on Fortress Road NW5, which served as the headquarters of the Reg Birch led Communist Party of Britain (Marxist-Leninist) - and was renowned for its more purist approach and the somewhat unwelcome atmosphere.[23][29] The other main outlet was Progressive Books and Periodicals, in the south of London on Old Kent Road. It was run by the Communist Party of England (Marxist-Leninist), a group infiltrated by SDS undercover 'HN13'[30] from 1974-78.[31][32]

Though as yet unconfirmed, it is believed Banner Book's proprietor, G. V. Bijur, was a member of the Association of Indian Communists, a relatively strong group from which leading Maoists of the era emerged. These include not only the Hampstead-based Abhimanyu Manchanda, but also Harrow-based Harpal Brar, of the Association of Communist Workers.[33] Both groups were active during the Vietnam protests of 1968 and afterwards - and both Manchanda, Brar (along with other individuals then closely connected to the RMLL) were named as such in Special Branch Files.[34] If the connection with the Association of Indian Communists holds through, then it also points to another potential target of Dave Robertson and Special Branch - the large Indian Workers Association, a leading anti-racism group in the 1970s under Jagmohan Joshi, a Birmingham-based Maoist.[33][35]

Threatening an activist

In her political memoir, author and activist Diane Langford writes of her time in the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League, headed by her husband Abhimanyu Manchanda:[14]

- From time to time the police infiltrated our group. A moustachioed Scottish man, Dave Robertson, aroused suspicion because he was always driving a different car. When challenged he claimed to be working for a car rental firm. On another occasion he’d told me he worked at a club called the Tatty Bogle.[36] One of the comrades went down to check it out and found this to be untrue. At Manu[chanda]’s suggestion, we didn’t confront Dave, but assigned him the most onerous tasks: collecting heavy banners and placards in his car and carrying them on marches. He was always called upon to buy everyone drinks and asked to memorise long passages from James Maxton, an obscure Scottish Marxist.

- The funny thing was, I quite liked Dave. He was always good-natured and went along with the aggravation. Then all that changed. The sinister nature of his work revealed itself.

- Through the Union, I’d got a job at the Daily Mirror and an Irish workmate, Ethel, came along with me to a meeting at the London School of Economics. John Gittings, a Guardian writer, Malcolm Caldwell of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Manu [Manchanda] and Pat Jordan of the International Marxist Group were getting an Indo-China Solidarity Committee together to respond to Nixon's bombing of Cambodia. Ethel was interested in becoming involved. Dave was there. When Ethel saw him, she greeted him brightly. ‘Oh, I know Dave,’ she said. He grabbed her by the wrist and said, ‘I want to talk to you outside.’ They didn’t come back.

- Next day at work, Ethel was cool and awkward with me. After a week of this she asked me to meet her for a drink.

- ‘Dave works for the special branch,’ she told me. ‘He’s threatened that if I tell you or Manchanda, he’ll cause something nasty to happen to my family in Ireland.’

- Dave disappeared off the radar and was never seen again. For a few months I scrutinised the faces under policeman’s helmets, wondering whether Dave had been demoted back to pounding pavements as a beat bobby.

As set out in the examination below, internal evidence indicates that this meeting likely took place in January 1973, or not long after.

Dating the threat

The passage provided by Diane Langford allows narrowing down when the threatening took place.

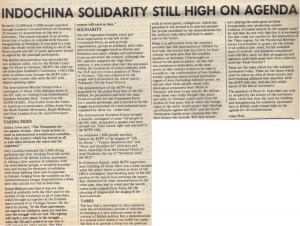

On 2nd / 3rd December 1972, an Indochina Solidarity Conference was held at Conway Hall in London. An advance notice for it listed among the speakers Gittings and Caldwell.[37] A report of the event appeared the following month in the Red Mole newspaper, titled: 'Basis laid for a new Indochina Campaign', which concludes:[38]

- Future Activity

But this political development has taken place amongst a tiny handful of people... A mass of duplicated propaganda on many aspects of the war was produced for the conference and this can provide the basis for education in the proposed Indochina Solidarity Committees.

In the New Year, regional conferences, preceded by speaking tours, will be organised...

The IMG wholeheartedly supports all proposals for ongoing activity in solidarity with the Indochinese peoples. We urge our readers who are interested in joining or forming an Indochina Solidarity Committee to write to ISC, 6 Endsleigh Street, WC1, or contact their nearest IMG branch or The Red Mole.

- Future Activity

At the time 6 Endsleigh Street was home to International Confederation for Peace and Development, under noted peace campaigner Peggy Duff, who at the time was also focusing on issue in south east Asia.

In the wake of renewed American bombing of Cambodia, an emergency demo was called by the Conference for 23rd December 1972, with a larger one taking place on 20 January 1973.[39][40][41]

Given that Dave Robertson is listed by the Inquiry as being deployed until 1973 it is likely he would have been around for the December protest. A search of publications from the time has not located any public meeting at the London School of Economics, which indicates it was likely a planning one. Meanwhile, articles on the December conference note calls for Indochina Solidarity Committees to be set up, implying they were not already in existence; while mentions of Indochina Solidarity Committee events do not start appearing until February/March 1973. Thus, a tight reading of Diane Langford's words and given that the priority in the wake of the December conference was planning for the protest of 20 January 1973, on balance of probabilities of what is currently known, likely that the incident were Dave Robertson threatened Ethel fell in that month.

Interest in such protests would have been a matter of routine concern for the SDS. The timing would also indicate that this identification was deemed too much of a compromise and lead to his deployment being ended.

In the Undercover Policing Inquiry

The Metropolitan Police Service made an application to restrict the real name only of HN45 on 31 July 2017, though that was not made public until May 2018.[42]

The anonymity application for HN45 was considered by the Chair of the Inquiry, Sir John Mitting, in his Minded-To note of 14 November 2017.[43] According to Mitting, HN45 is currently in his 70s, and had been deployed against groups in the 1970s, from which there was no known allegation of misconduct. Later, the officer had an administrative role in SDS in the period 1982-1983 which involved collation & internal distribution of intelligence reports, but 'not the tasking of undercover officers or target group selection.'

- Only immediate family members are aware of HN45’s deployment. They are concerned about the damage to HN45’s reputation which might result from association in the real name with other now notorious undercover officers and from lies which might be told by others about HN45. HN45 undertook the role of an undercover officer in the expectation that identity would not be revealed. In respect of real identity, this expectation should be fulfilled unless it is in the public interest that it should be set aside – for example, if it were necessary to do so to permit an accusation of misconduct to be determined. It is not. Further, reputation is an aspect of HN45’s private life to which respect must be shown. Interference with it is not necessary to fulfil the terms of reference of the Inquiry.

- The same considerations do not apply to the cover name. I accept, as claimed, that HN45 understood that the cover name would not be revealed publicly. I also accept, as contended, that it is unlikely that any member of any of the groups encountered by this officer, will be able to give evidence about the deployment because of the elapse of time and the death of the principal target. I cannot, however, exclude the possibility that disclosure of the cover name may prompt such evidence and that it may be necessary to receive it to fulfil the terms of reference of the Inquiry. I am satisfied on the basis of the risk assessment dated 10 July 2017 that the risk that disclosure of the cover name would lead to the identification of HN45 by real name is nil or negligible. In those circumstances, the balance of factors requires that the cover name is published.

Closed reasons were also provided. On 4 January 2018 the open application for restriction order was released, but not Impact statement or Risk Assessment. The cover name and two of the target groups (Banner Books & VSC) were released on 17 April 2018.[1] Mitting ruled on 15 May 2018 that the real name would be restricted, the cover name having already been released.[44]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Undercover Policing Inquiry, Update of Cover names page, ucpi.org.uk, 17 April 2018 (accessed 17 April 2018).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 John Mitting, In the matter of section 19 (3) of the Inquiries Act 2005 Applications for restriction orders in respect of the real and cover names of officers of the Special Operations Squad and the Special Demonstrations Squad ‘Minded to’ Note 2, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 14 November 2017 (accessed 15 November 2017).

- ↑ HN45 gist of additional information from supporting evidence, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 2018.

- ↑ The Communist Party, Abhimanyu Manchanda Remembered (website), July 2015 (accessed 5 May 2018).

- ↑ Graham Stevenson, Dennis Goodwin (biographical sketch), GrahamStevenson.co.uk, undated (accessed 7 May 2018).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Marxists.org, undated (accessed 1 May 2018).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Donal O'Driscoll, 1968 - Protest and Special Branch, SpecialBranchFiles.uk, 14 April 2018 (accessed 5 May 2018).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 1968, Grosvenor Square – that’s where the protest should be made, WoodsmokeBlog, 18 August 2017 (accessed 5 May 2018).

- ↑ A. Manchanda, Memorandum submitted to the Secretariat of the Provisional Committee of the British Marxist-Leninist Organisation, 24 February 1968 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- ↑ The Student Movement and the Second Wave: Maoists and the RSSF experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line, undated (accessed 5 May 2018).

- ↑ Mary McCarthy, Letter from London: The Demo, New York Review of Books, Vol. 11, No. 11, 19 December 1968 (accessed via the AbhimanyuManchandaRemembe.

- ↑ The Second Wave: the Radical Youth Wants a Party: The Late 1960s – Index Page, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line, undated (accessed 7 May 2018).

- ↑ Papers of Abhimanyu Manchanda & Claudia Jones (index), Marx Memorial Library, September 2015 (accessed 6 May 2018).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Diane Langford, The Manchanda Connection, Abhimanyu Manchanda Remembered (website), July 2015 (accessed 5 May 2018).

- ↑ Peter Hennessy, The Secret State: Preparing For The Worst 1945 - 2010, Penguin UK, 27 March 2014.

- ↑ Donal O'Driscoll, 1968: Protest and Special Branch, 14 April 2018 (accessed 7 May 2018).

- ↑ 'John Graham' (alias), Impact / Personal Statement by HN329 (open version), Metropolitan Police Service (via UCPI.org.uk), 29 March 2017 (accessed 5 August 2017).

- ↑ David Reid, HN329 Open Risk Assessment, Metropolitan Police Service (via UCPI.org.uk), 31 May 2017 (accessed 3 August 2017).

- ↑ Leonora Lloyd, Booklist for Women's Liberation, London Socialist Women's group November 1970 (accessed via Marxists.org)

- ↑ Graham Walker, HN348 Risk Assessment - Gisted - Version 2, Metropolitan Police Service, 17 July 2017 (accessed via ucpi.org.uk).

- ↑ Banner Books and Crafts Ltd, CompanyCheck.co.uk, undated (accessed 5 May 2018).

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Pamphlets, Bookshops and Places of Interest, WoodsmokeBlog, October 2016 (accessed 5 May 2018).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Radical Bookshops History Project (Radical Bookshops Listing), LeftOnTheShelfBooks.co.uk, undated, (accessed 5 May 2018).

- ↑ Paul Pawlowski, A page of current history of England (post on internet discussion board), IndianCulture.net, 17 August 2006 (accessed 5 May 2018).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Letter of Richard Gibson to Marika Sherwood of 10 July 2010, accessed via AbhimanyuManchandaRemembered.weebly.com (accessed 5 May 2018).

- ↑ Undercover Research Group: interview with Albert Beale, 3 May 2018.

- ↑ Banner Books and Crafts Ltd was struck off as a company in 1977. See List 6792, The London Gazette, 10 February 1977 (accessed 5 May 2018).

- ↑ High Tide - citing Class Struggle, March 1984, Marxists.org, undated (accessed 5 May 2018).

- ↑ Alexei Sayle, Stalin Ate My Homework, Hachette Books, September 2010.

- ↑ See also Undercover Research Group, N officers, 2018.

- ↑ Amy Jane Barnes, From Revolution to Commie Kitsch: (Re)-presenting China in Contemporary British Museums through the Visual Culture of the Cultural Revolution (PhD thesis), University of Leicester, September 2009 (accessed 5 May 2018).

- ↑ Progressive Books later moved to Wandsworth, where it became the John Buckle Centre, the headquarters of the Revolutionary Communist Party of Britain (Marxist–Leninist), the successor organisation of the Communist Party of England (Marxist-Leninist).

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 The IWA (GB), Indian Communists & the AIC, WoodsmokeBlog, 5 January 2017 (accessed 5 May 2018)

- ↑ Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive”, weekly summary, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 16 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).

- ↑ Diane Langford in her memoir (vide infra) talks of going to visit Maoist colleagues of Manchanda's in Birmingham in the early 1970s.

- ↑ The Tatty Bogle was a noted private club at Kingly Court, Soho.

- ↑ The notice for the conference on Page 8 of issue 55 the Red Mole newspaper, which lists speakers as Gittings and Caldwell - along with Noam Chomsky, Steven and Hilary Rose, Robin Blackburn (International Marxist Group) as well as representatives from the Provisional Representative Government of South Vietnam, Democratic Republic of Vietnam, Laotian and Cambodian organisations. See: Indochina Solidarity Conference, Red Mole, vol.3, no. 55, 13 November 1972.

- ↑ John Weal, Basis laid for a new Indochina campaign, Red Mole, vol.3, no. 57, 11 December 1972.

- ↑ Labour and Indochina, Red Mole, Vol. 4, No.58, 8 January 1973 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- ↑ Joan Stott, All out for January 20th!, Red Mole, Vol. 4, No.58, 8 January 1973 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- ↑ John Weal, Indochina solidarity still high on agenda, 'Red Mole, Vol. 4, No.60, 3 February 1973 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- ↑ Open application for a restriction order (anonymity) re: HN45, Metropolitan Police Service, 31 July 2017, published 8 May 2018 at ucpi.org.uk.

- ↑ In the matter of section 19 (3) of the Inquiries Act 2005 Applications for restriction orders in respect of the real and cover names of officers of the Special Operations Squad and the Special Demonstrations Squad ‘Minded to’ note 2, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 14 November 2017.

- ↑ In the matter of section 19 (3) of the Inquiries Act 2005 Applications for restriction orders in respect of the real and cover names of officers of the Special Operations Squad and the Special Demonstrations Squad: Ruling, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 15 May 2018.