Paul Wilkinson

Professor Paul Wilkinson (born 9 May 1937) is chairman of the Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence at St Andrews University. He is one of the foremost academic terrorologists in the UK and a has served as an active propagandist for Western state interests throughout his long career. He retired from academia in October 2007 but continues to be involved in terrorology.

Contents

Biographical information

Early life

Born on 9 May 1937 to Walter and Joan Wilkinson, Paul Wilkinson attended John Lyons School, a private school in Harrow loosely affiliated with the more prestigious Harrow School. He studied History and Politics at University College in Swansea - now Swansea University but then part of the University of Wales. After graduating in 1959 he joined the RAF as an education officer [1] where he served for six years until 1965 when he retired at the rank of Flight Lieutenant.[2]

Wilkinson says his interest in terrorism dates back to his time at the RAF. He told The Herald that during this time he travelled the country "sorting out libraries" and, because there wasn't much to do, spent plenty of time reading. [3] “I wrote about groups involved in protest, revolution and revolt in places like the Middle East – the sub-state actors rather than states," he told The Guardian, "It started as a short project for an article but the whole subject took off and turned into a major research field” [4]

In Cardiff

In 1966 Wilkinson embarked on his academic career. He returned to the University of Wales, this time to Cardiff, where he became assistant lecturer in Politics. He spent 14 years based in Cardiff, and was promoted to lecturer in 1968, senior lecturer in 1975 and then Reader in 1978.[5] Whilst at Cardiff he published his first book, Social Movement (1971) and three years later produced his first book on terrorism entitled Political Terrorism (1974). The book, according to one reviewer, built “on three best previous treatments, by Brian Crozier (1960), Thomas Thronton (1964), and E. V. Walter (1969).” In the book, that reviewer noted, Wilkinson “candidly tells us one of his aims is identifying counter-measures to terrorist attacks on liberal democracies”[6] He urged liberal democracies to “never surrender to blackmail or extortion” because if acts of terrorism “are seen to pay, then inevitably…the terrorists’ demands will escalate.” [7] Alex Schmid later recalled that one chapter “addressed the issue of ‘Terror against liberal democracies’ - a theme that would occupy [Wilkinson] for the rest of his life.” [8] Indeed Wilkinson’s Manichaean portrayal of a struggle between extremist terrorists and liberal democracies became a common thread in his writings, and naturally made him appealing to Western elites. The theme was more explicitly developed two years later in Terrorism versus Liberal Democracy published as part of the Conflict Studies journal series by the Institute for the Study of Conflict; a pseudo-academic outfit established by a group of right-wing ideologues with connections to the secret services. In 1977 Wilkinson followed up Terrorism versus Liberal Democracy with Terrorism and the Liberal State, a more influential book which would be revised and republished in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Reviewing the book on its original release, The Economist wrote:

[One] main concern of the book, as the title suggests, is to persuade liberals to take up tougher weapons in defence of their system. Mr Wilkinson, in the most interesting chapter of his book, believes that terrorism in Ulster could have been defeated if the government had gone on with the policy of internment, thorough intelligence gathering and freedom for the army to shoot as it saw fit and on sight.[9]

At the book's launch in October 1977, Wilkinson warned the media that London was becoming a haven for terrorists. “They wish to take advantage of our democratic freedom,” he told The Guardian. [10]

In Aberdeen

In 1979 Wilkinson moved to Aberdeen University where he was appointed the first Chair in International Relations.

On 27 October 1980 Wilkinson joined the Institute for the Study of Conflict, which had published his book Terrorism versus Liberal Democracy four years earlier. Wilkinson spent only a short time at the Institute, and resigned from the Council on 26 May 1981.[11]

Interestingly it later emerged that Wilkinson had met with the notorious Oliver North in 1984. It was revealed during the Congressional hearings into the Iran-Contra scandal that North's schedule for 10 September 1984 included two one-and-a-half hour encounters with Wilkinson. When questioned by The Guardian on the disclosures Wilkinson said North’s schedule must have referred to lectures he had given in Washington, saying, “I'm sure I'd have remembered them otherwise.”[12]

In 1985 Wilkinson was made head of the Department of Politics and International Relations at Aberdeen University. He established The Terrorism Research Unit within the department and began to develop a computer database containing a chronology of terrorist incidents, profiles of terrorist groups and laws and anti-terrorist measures taken by governments.[13] This project - described as being 'unique in size in Western Europe' - was coordinated with the RAND Corporation and the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies at Tel-Aviv University (where Ariel Merari was working on a similar project).[14] This project almost certainly led to the RAND-St Andrews database developed by Wilkinson and Bruce Hoffman in the 1990s at the Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence.

In late 1986 Wilkinson founded the Research Foundation for the Study of Terrorism, a corporate funded 'charity' which shared an office with the right-wing lobby group Aims of Industry, but was occasionally (and probably inaccurately) reported to be based at Aberdeen. Wilkinson wrote to major corporations to ask for donations of up to £10,000 to fund 'a major research project on terrorist threats to industry by product contamination and methods of combatting them.'[15]

After the Lockerbie Bombing in December 1988, Wilkinson – along with other terrorologists – developed an interest in aviation security. Following the bombing he advised the British Department of Transport and assisted the American Federal Aviation Administration.[16] His Research Foundation for the Study of Terrorism published Lessons of Lockerbie in 1989 and became an early advocate for high-technology ID cards, calling for the ‘replacement of passports by high-technology identity cards, which would include fingerprint information.’[17] Several years later he would co-author Aviation Terrorism and Security with Brian Jenkins, another key figure in the early years of terrorism studies.

At St. Andrews

In 1989 Wilkinson left Aberdeen to join the University of St. Andrews as Professor of International Relations. Wilkinson introduced two new courses at St. Andrews, one of course in International Terrorism and another in Comparative Intelligence Systems. The Times called them 'the most controversial courses yet offered in British universities'.[18] Wilkinson taught the terrorism course which was aimed at influencing future state and corporate personnel: "I would hope that our graduates would put their training to good use in government, industry, the armed forces, the Foreign Office or the law," Wilkinson told The Times.[19] The Comparative Intelligence Systems course was headed by Myles Robertson, a Kremlinologist who planned the course over six months with the help of "former government people."[20]

In December 1989 Wilkinson became a director of the Research Institute for the Study of Conflict and Terrorism,[21] a new think-tank which was formed by amalgamating the Research Foundation for the Study of Terrorism with the Institute for the Study of Conflict[22] (which had published Terrorism versus Liberal Democracy).

In the wake of the first Gulf War, Wilkinson was openly critical of the hasty resort to force and authored an op-ed in The Guardian warning of the potential loss of civilian lives; a stance rather unusual for a 'terrorism expert'. He was also critical of ‘British people [who] have come to tamely accept the idea that Britain should unquestioningly follow the bidding of the US President.’[23] However, this analysis was coupled with dire warnings of the potential terrorist threat Saddam Hussein might pose. He told the Press Association that “once hostilities have broken out, Saddam will order ruthless attacks on civilian targets, such as airlines, check-in desks and other public places without any compunction.”[24] He told The Times, “We do have evidence that the dangerous groups really experienced in terrorism who receive substantial sponsorship in terms of money, training and intelligence from Saddam, are in place ready to launch attacks when he gives the word.”[25]

In 1994 Wilkinson resigned from the board of the Research Institute for the Study of Conflict and Terrorism and was appointed head of the School of History and International Relations (a post he held until 1996). 1994 was also the year Wilkinson founded the Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence with RAND analyst Bruce Hoffman. Wilkinson was appointed a director of CSTPV in 1999 and a Chairman in 2002.

Into retirement

In October 2007 Wilkinson officially retired from St. Andrews but he remains Chairman of the Advisory Board of CSTPV.[26]

Influence on policy makers

European policy

On 13 November 1980 the Council of Europe held a terrorism conference in Strasbourg. According to a Spanish radio broadcast translated by the BBC, “The international conference on terrorism…brought together 100 or so European experts.” [27] Wilkinson was one of them. At the conference he reportedly urged for laws to prosecute the BBC for interviewing the killers of the British politician Airey Neave, and for filming an IRA road block. He said: “Certain employees wilfully conspire or collaborate with terrorists and allow their programmes to become vehicles for terrorist propaganda.” [28]

According to The Guardian a secret session on security measures was held during the conference. It was attended by academics, policemen and politicians, but was “dominated” by Wilkinson and Richard Clutterbuck. [29] Clutterbuck, a counter-insurgency expert, was a former Council member of the Institute for the Study of Conflict, which Wilkinson had recently joined. [30] Years later he would become involved in Wilkinson's Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence.

The session discussed “an international intelligence computer, a kind of Euro-MI5 and international commando squads.” [31] Clutterbuck and Wilkinson agreed on the computer proposal but not on Wilkinson’s proposal for “a central coordinating cell of half a dozen security and intelligence experts” to strengthen intelligence links between European states. [32] In addition to his proposals for “a small permanent European Commission to improve international co-ordinating”, Wilkinson also proposed SAS style “hostage rescue squads for other regions of the world”. [33]

In November 2004 Wilkinson told the Parliamentary Select Committee on the European Union that he was "due to meet [the EU Counter-terrorism Co-ordinator] very shortly" [34]

Government consultant and the Lloyd Inquiry

Wilkinson appears to have first been consulted by the government on its anti-terrorism policy in the early 1980s. In 1982 he gave written and oral evidence to the Home Office's review of the Operation of the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act 1976, [35] and a year later was consulted by the Northern Ireland Office in the review of the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1978. [36] In 1987 was consulted again by the Home Office for its review of the Operation of the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act 1984. [37] His most significant contribution to policy however was his involvement in the Lloyd Inquiry.

In December 1995 the Conservative Government set up an inquiry into anti-terrorism legislation in the UK. At that stage British anti-terrorism legislation was limited to a series of temporary emergency powers designed specifically to targeting the IRA and other militant groups in Northern Ireland. The inquiry set up to review the existing legislation was headed by Lord Lloyd of Berwick and published its report in October 1996. Wilkinson was not only an advisor to Lord Lloyd, he even authored the second part of the report.[38] The main report, which Lord Lloyd admitted had “drawn heavily”[39] on Wilkinson’s research, essentially recommended the indefinite extension of the Draconian powers until then limited to Northern Ireland to the rest of the UK and concluded that there was “a continuing need for permanent United Kingdom-wide legislation.”[40] It also recommended that the government develop an official list of organisations prescribed as terrorist - a key mechanism used by states to condemn acts of terrorism committed by enemies whilst exonerating allies. The report was part of a legislative process which led to the Labour Government's Terrorism Act 2000.[41]

Not only was Wilkinson connected with the inquiry which led to the Terrorism Act 2000, but he is also connected to Lord Carlile, the supposedly independent reviewer of the United Kingdom’s anti-terrorism legislation. In November 2005 Lord Carlile told the House of Lords he considered Wilkinson “the greatest non-lawyer expert in this country… on terrorist organisations around the world.” He also commented offhand that he had “sat in Professor Paul Wilkinson's interesting attic office in the University of St Andrew's Centre for the Study of Terrorism.”[42]

On Friday 11 July 1997 Wilkinson attended an MoD seminar organised by the new Labour government on its Strategic Defence Review. The seminar was chaired by the diplomat turned investment banker Michael Alexander and attended by 19 other academics, journalists and think-tank members. [43]

Consultant to Parliamentary Committees

Wilkinson gave evidence to the Defence Select Committee in its 94/95 and 95/96 sessions. [44] After the attacks on the World Trade Center in September 11, 2001, Wilkinson appeared at numerous parliamentary committees offering his wisdom on terrorism and security. In October 2001 he was appointed a special advisor to the Select Committee on Defence, and in January 2002 he made the first of several appearances before the Foreign Affairs Select Committee[45] as part of its series of reports on ‘Foreign Policy Aspects of the War against Terrorism’. Evidently, however, the chairman of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee was already a fan. Donald Anderson, who chaired the Committee from 1997 until 2005, recommended Wilkinson’s book Terrorism versus Democracy to the House of Commons three days after September 11th. It was, he said, “an excellent work”.[46] The day before, Anderson and Wilkinson had both appeared on the BBC current affairs programme World At One[47] but their connection probably goes back much further than that; both men studied Politics and History at the Swansea College and graduated only a year apart from each other.[48]

In addition to his appearances before the Defence and Foreign Affairs Committees, Wilkinson has given evidence on terrorism-related reports compiled by the European Union Select Committee,[49] and the Transport Committee[50]

Propaganda connections

Testifying for the British government

Wilkinson gave evidence for the British government in 1983/4 in their case for the extradition of Maze prison escaper Joe Doherty in the US. The Belfast journalist, Martin Dillon, has recounted the British government's invitation to him to give evidence in the US at court hearings held to consider the extradition of Republican prisoner Joe Doherty. One 'classified' British government memorandum he received, while making a decision about whether to testify, revealed government strategy, outlined at a meeting in July 1983:

- It would be prudent for the Northern Ireland Office during the period leading up to the defence's response to our depositions, to give thought to possible witnesses on the general situation in the Province at the time of Doherty's offences. It would be important for any such witness to be dissociated from the British Government, and for him to be able to paint a picture of declining violence and impartial law enforcement and judicial procedures. While such high profile figures as Conor Cruise O'Brien, Lord Fitt or Robert Kee could be difficult to land, the bigger the 'fish' the better.[51]

In the event Dillon declined the offer and his place was taken by Professor Paul Wilkinson of St Andrews University - who was presumably viewed as a smaller 'fish'.[52]

Wilkinson & Colin Wallace

In 1986 Wilkinson intervened in the 'Colin Wallace' affair. The Information Policy unit set up in Northern Ireland in 1971 was connected to the Information Research Department-run psychological warfare operations headed by Jeremy Railton and Maurice Tugwell. Tugwell, according to Edward Herman and Gerry O'Sullivan, is an old ally of Paul Wilkinson, having participated in Wilkinson's conference in Aberdeen in April 1986, as well as contributing a chapter to a Wilkinson-edited volume, 'British Perspectives on Terrorism.'

In the summer of 1987 rumours were spread through a small group of journalists that Colin Wallace's claims to have been a sky-diver were false and that this indicated that his wider claims concerning government covert operations were also false and that he was a fantasist, a' Walter Mitty'. These rumours arrived at Channel Four News who had been one of the few media outlets to cover Wallace's claims and prompted other journalists such as Paul Foot and Robin Ramsay (who were convinced that Wallace's sky-diving stories were as true as his other claims).

But when Ramsay contacted the British Parachuting Association to check their file on Wallace he found they had no record of him. Eventually Paul Foot discovered that a duplicate set of records were held by the international parachuting body and Wallace's records were there, confirming that he was what he said he was — as far as sky-diving went.[53] A journalist now with the BBC, John Ware, still ran the 'Wallace-is-a-fake' parachuting story some months later in a double page spread in the Independent smearing both Wallace and Fred Holroyd.

Ramsay [54]argues that:

- The point here is, we can now work out some of what this MOD-MI5 operation against Wallace consisted of. First, they picked one area of Wallace's CV, his parachuting, and set out to discredit him with it. If they could show he was lying here, they believed, journalists would not believe his other claims. They burgled his house and stole his jumping log book; they burgled the British Parachuting Association and removed his file, substituting a fake file for the one with his number on it. Then they began spreading the word through their press contacts that Wallace was a fraud, knowing that Wallace didn't have his jumping log and knowing that —eventually —some journalist would ring the British Parachuting Association and ask about his record. Finding nothing, because his file had been removed, such a journalist would consider the allegation that he was a fantasist proven and would thus dismiss him as the 'Walter Mitty' figure described at his trial. This operation was certainly run at Channel Four News and John Ware, then working for the BBC.

Without Foot's investigation journalists would have been struggling to rebut the Wallace-is-a fantasist line. Ramsay argues that another disinformation project about Wallace was fed through Paul Wilkinson, then at Aberdeen University, and ITN's official consultant on terrorism.

- Somebody in the MOD or MI5 fed him some material about Wallace which accused him of trying to get a man in Northern Ireland killed so he —Wallace —could have the man's wife. This smear story had been created just before Wallace left Northern Ireland —presumably in case they ever needed to get at Wallace. Wilkinson wrote a letter, passing this derogatory material on to ITN. Fortunately, by this point,Channel Four News' management were pretty sure Wallace was telling the truth and showed us journalists Wilkinson's letter. The allegations it contained were refutable, and Wallace wrote to the University authorities. Wilkinson was reprimanded and apologised and lost his job as ITN's consultant on terrorism. The point here is this: Wallace had already been framed for manslaughter and convicted in a rigged trial. Having failed to shut Wallace up with six years of imprisonment, the secret state then set about discrediting him. If you could get to the people on the MOD/MI5 committee which planned this and asked them why they were doing it, they would simply say, it was in the national interest to prevent Wallace talking. In the minds of the secret state the national interest —as defined by them—overrides the competing claims of justice and democracy.

Edward S. Herman and Gerry O'Sullivan provide this analysis of the affair in their book The 'Terrorism' Industry:

- Wilkinson's service to a repressive state was carried to a new level in his attempt to discredit Colin Wallace, formerly of MI5 (British intelligence) and the Army Information Department. Wallace had exposed the workings of an MI5-backed "dirty tricks" campaign designed to discredit Labour MPs by linking their names, prior to elections, with the Irish Republican Army, as well as an MI5 campaign to smear Harold Wilson in 1976. Wallace also went on record in exposing abuses of psychological operations undertaken against the Irish by British intelligence.[55]

- In response to Wallace's charges, Wilkinson passed along a letter of dubious origin to ITN Television, which accused Wallace of all manner of wrongdoing. Wilkinson's accompanying letter (on University of Aberdeen stationery and dated July 21, 1987) to a representative of ITN began, "Herewith the interesting letter I received from one of our researchers on the Colin Wallace affair. . . . It certainly raises major question marks about the extent to which one can rely on his version of events in Northern Ireland and elsewhere."[56]

- The letter in question, a rather crude piece of disinformation, wrongfully accused Wallace of attempting to have the husband of a woman he was allegedly having an affair with killed by the Ulster Defence Association, and attributed his claims regarding Wilson and MI5 to 'James Bond fantasies.' Subsequently, in a letter to Wallace himself dated June 9, 1988, Wilkinson apologized for having caused him any undue "discomfort or embarrassment." A letter of retraction was simultaneously sent to various news agencies calling the allegations against Wallace (which he had, in essence, provided as fact) "totally untrue."[57]

Media presence

Television and Radio

On 3 January 1987 BBC 1 broadcast Crisis!, a documentary cum drama surrounding an imaginary hijacking and hostage crisis. The concept was that a committee of MPs and experts, chaired by Wilkinson, would have to make to deal with the imaginary emergency. Other participants included Roy Jenkins, Francis Pym and Gerald Kaufman. [58]

In 1990 The Observer said Wilkinson was “a familiar voice on the radio following any terrorist outrage when his views as ‘an expert’ are eagerly sought by Brian Redhead [presenter on BBC Radio 4's Today Programme] and others.” [59]

Print Media

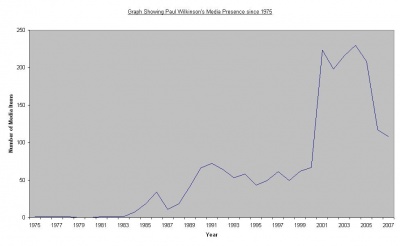

The graph on the right shows Wilkinson’s presence in the English print media from 1975 until the end of 2007. The figures were compiled by searching All English Language News at Lexis-Nexis for references to Terrorism and Paul Wilkinson.[60]

The graph shows a significant increase following Wilkinson’s move to St. Andrews in 1989, which also coincided with media discussion of the Lockerbie bombing. As you might expect it also shows an enormous increase following the September 11th terrorist attacks.

Writings and views

Wilkinson became a leading expert on terrorism setting the agenda for public debate, not just in the academy but in the media, policy circles and in relation to thin tanks and the legal system. His writing on terrorism are notable however, for their lack of engagement with empirical research and for their over-reliance on official sources and media reports. It is notable however, that only those sources which do not contradict his views were in general cited or used as 'evidence'. Although Wilkinson is often treated as if he were a dispassionate and simply 'expert' analyst, there is little to distinguish his views or analysis from that of the counterinsurgency theorists produced

Views on definitions of Terrorism

According to David Miller:

- Thus Paul Wilkinson, the 'doyen' [61] of British terrorism studies, has suggested that debate about the meaning and use of the term 'terrorism' may simply be a device to obstruct 'anti-terrorist' policies:

- The problems of establishing a degree of common understanding of the concept of terrorism have been vastly exaggerated. Indeed, I suspect that some have tried to deny that any common usage exists as a device for obstructing co-operation in policies to combat terrorism. [62]

- For such writers the only worthwhile argument concerns how to increase the effectiveness of 'anti-terrorist' policies. Should we choose to question the assumptions in such an approach, the ideological policing of the counterinsurgents will label us as fellow travellers of the 'terrorists'. But in truth there is no universal agreement on the causes of the Northern Ireland conflict and the term 'terrorism' is not unambiguous in its meaning and use.[63]

Resources

Spinprofiles Resources

External Resources

Publications

- Social Movement (1971)

- Political Terrorism (1974).

- Terrorism versus Liberal Democracy (1976) published by the Institute for the Study of Conflict

- Wilkinson, Paul (1977) Terrorism and the Liberal State, London:Macmillan.

- Wilkinson, Paul and Stewart, Alasdair (eds) (1987) Contemporary Research on Terrorism. Aberdeen : Aberdeen University Press.

- Terrorism: International Dimensions (1979)

- The New Fascists (1981)

- The New Fascists (second edition) (1983)

- Terrorism and the Liberal State (second edition) (1986)

- Wilkinson, Paul (1987) Kidnap and Ransom in P Wilkinson and A Stewart, Contemporary Research on Terrorism. Aberdeen : Aberdeen University Press.

- Wilkinson, Paul (1987) 'Can a State be Terrorist?', International Affairs. 57 : 467-472.

- Wilkinson, Paul (1988) 'The Future of Terrorism', Futures. Vol 20 No 5, October : 493-504.

- Lessons of Lockerbie (1989)

- Terrorist Targets and Tactics (1990)

- Wilkinson, Paul (1990) 'Terrorism and Propaganda' in Y. Alexander R. and Latter (eds) Terrorism and the Media: Dilemmas for Government, Journalists and the Public, Washington:Brassey's

- The Victims of Terrorism research report of the Airey Neave Trust (1994)

- Combating International Terrorism (1995)

- Inquiry into Legislation Against Terrorism volume two, research report (1996)

- Aviation Terrorism and Security by Paul Wilkinson ISBN10 0714644633 | ISBN13 9780714644639 | Publication Date: 1st March 1999 | Edition: Revised edition |

- Terrorism versus Democracy The Liberal State Response by Paul Wilkinson ISBN10 0714681652 | ISBN13 9780714681658 | Publication Date: 1st November 2000, Frank Cass, 2nd Ed. 2006

- Terrorism Versus Democracy: The Liberal State Response, Second Edition revised and updated (2006)

- Paul Wilkinson, (2007) International Relations: A Very Short Introduction, OUP

- Paul Wilkinson (Ed.), (2007) Homeland Security in the UK, Routledge.

Jointly Authored/Edited

Terrorism: Theory and Practice (1978) British Perspectives on Terrorism (1981) Contemporary Research on Terrorism (1986) Terrorism and International Order (1986) Technology and Terrorism (1993) Terrorism: British Perspectives (1993) Aviation Terrorism and Security (1999) Addressing the New Terrorism (2003) Terrorism and Human Rights (2006)

Notes

- ↑ Alan Crawford, 'Rising In The East', The Sunday Herald. 12 January 2003

- ↑ entry in Debrett's People of Today (Debrett's Peerage Ltd, November 2007)

- ↑ Vicky Allan, 'We are the guardians of the world', The Herald, 11 April 2004

- ↑ Dennis Barker, ‘Professor with a fatal fascination’, The Guardian, 7 December 1989

- ↑ entry in Debrett's People of Today (Debrett's Peerage Ltd, November 2007)

- ↑ R. L. Nichols, review of Political Terrorism by Paul Wilkinson in The American Political Science Review, Vol. 72, No. 2, (Jun., 1978), pp. 660-661

- ↑ Daniel N. Nelson, review of Political Terrorism by Paul Wilkinson in The Journal of Politics, Vol. 38, No. 4 (Nov., 1976), pp. 1058-1059

- ↑ Speech given by Professor Alex P. Schmid on the occasion of Paul’s retrial. Accessed from URL <http://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/~cstpv/about/staffprofiles/pwretiral101007.pdf> on 28 June 2008, 13:47:59

- ↑ The Economist, 29 October 1977

- ↑ Alec Hartley, ‘‘Haven’ for terrorists’, The Guardian, 19 October 1977, page 6

- ↑ Institute for the Study of Conflict Ltd, Extract from the Report by the Members of the Council of Management on the Accounts for the Year Ending 30th June 1981, filed at Companies House on 9 November 1981

- ↑ Seumas Milne, The Guardian, 14 March 1989

- ↑ Alex Peter Schmid, Political terrorism: a new guide to actors, authors, concepts, data bases, theories and literature (Amsterdam; Oxford: North-Holland, 1988) pp.146-147)

- ↑ Alex Peter Schmid, Political terrorism: a new guide to actors, authors, concepts, data bases, theories and literature (Amsterdam; Oxford: North-Holland, 1988) pp.146-147)

- ↑ Carol Leonard, ‘City Diary: Terror tactics’, The Times, 4 January 1988

- ↑ Speech given by Professor Alex P. Schmid on the occasion of Paul’s retrial. Accessed from URL <http://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/~cstpv/about/staffprofiles/pwretiral101007.pdf> on 28 June 2008, 13:47:59

- ↑ David Sapstead, ‘Pilots warn of poor security standards at most airports’, The Times, 2 January 1989

- ↑ Barnaby Jameson, 'Terror goes on the agenda', The Times, 3 June 1991

- ↑ Barnaby Jameson, 'Terror goes on the agenda', The Times, 3 June 1991

- ↑ Barnaby Jameson, 'Terror goes on the agenda', The Times, 3 June 1991

- ↑ entry in Debrett's People of Today (Debrett's Peerage Ltd, November 2007)

- ↑ William Greaves, 'A thinking man's war', The Times, 9 May 1989

- ↑ Paul Wilkinson, ‘A way to avoid the no-win war’, The Guardian, 3 January 1991

- ↑ Grania Langdon-Down, ‘Terror groups could hit Britain before Gulf War’, Press Association, 31 December 1990

- ↑ Quentin Cowdry and Stewart Tendler, ‘Yard tightens security in alert for terror acts’, The Times, 11 January 1991

- ↑ Speech given by Professor Alex P. Schmid on the occasion of Paul’s retrial. Accessed from URL <http://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/~cstpv/about/staffprofiles/pwretiral101007.pdf> on 28 June 2008, 13:47:59

- ↑ ‘French Foreign Minister's Visit to France: Friction over ETA’, BBC Summary of World Broadcasts, 19 November 1980, SOURCE: Madrid in Spanish for Europe 1830 gmt 17 Nov 80 (i) Excerpts from Paris dispatch by Carlos Castillo

- ↑ David Leigh, ‘The victims are still piling up’, The Guardian, 15 November 1980, pg. 17

- ↑ David Leigh, ‘Euro-moves to combat growth of terrorism, The Guardian, 14 November 1980, p.3

- ↑ Institute for the Study of Conflict Ltd, Extract from the Report by the Members of the Council of Management on the Accounts for the Year Ending 30th June 1981, filed at Companies House on 9 November 1981

- ↑ David Leigh, ‘Euro-moves to combat growth of terrorism, The Guardian, 14 November 1980, p.3

- ↑ David Leigh, ‘Euro-moves to combat growth of terrorism, The Guardian, 14 November 1980, p.3

- ↑ Paul Wilkinson, ‘Protecting innocents’, The Observer, 23 November 1980, p.12

- ↑ Minutes of Evidence of the Select Committee on European Union (17 November 2004)

- ↑ 1982/83 Cmnd. 8803 Home Office: Review of the Operation of the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act 1976. (Chairman: Lord Jellicoe)

- ↑ 1983/84 Cmnd. 9222 Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1978 Review; Northern Ireland Office: Review of the operation of the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1978. Chairman: Sir George Baker

- ↑ 1987/88 Cm 264 Home Office: Review of the Operation of the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act 1984

- ↑ Inquiry Into Legislation Against Terrorism (CM3420, vol 2) (1996), authorship credited in Wilkinson’s entry in Debrett's People of Today (Debrett's Peerage Ltd, November 2007)

- ↑ Colin Brown, ‘Ministers said to be soft on terrorism’, The Independent, 2 November 1996

- ↑ Legislation Against Terrorism (Cm 4178), A consultation paper, Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for the Home Department and the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland by Command of Her Majesty December 1998

- ↑ Part 4. of the Explanatory Notes to Terrorism Act 2000 reads: “The Act builds on the proposals in the Government's consultation document Legislation against terrorism (Cm 4178), published in December 1998. The consultation document in turn responded to Lord Lloyd of Berwick's Inquiry into legislation against terrorism (Cm 3420), published in October 1996.”

- ↑ Hansard HL Volume 675 Column 1436 (21 November 2005)

- ↑ [Memorandum] submitted by the Ministry of Defence to the Select Committee on Defence on seminars held on the Strategic Defence Review

- ↑ 1994/95 HC 837 Defence Select Committee: Minutes of proceedings of the Defence Select Committee, session 1994/95; 1995/96 HC 300 Defence Select Committee: NATOs southern flank. Defence Select Committees third report with proceedings. (Including HC 373 1994/95)

- ↑ Oral Evidence of Paul Wilkinson to the Foreign Affairs Select Committee

- ↑ Hansard HC, Volume No. 372 Column 629 (14 September 2001)

- ↑ World At One How to dismantle the terror networks?, 13 September 2001

- ↑ see BBC News Vote 2001 Candidates Donald Anderson and Speech given by Professor Alex P. Schmid on the occasion of Paul’s retrial. Accessed from URL <http://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/~cstpv/about/staffprofiles/pwretiral101007.pdf> on 28 June 2008, 13:47:59

- ↑ Minutes of Evidence of the Select Committee on European Union (17 November 2004)

- ↑ Transport Committee Formal Minutes, PROCEEDINGS OF THE COMMITTEE Wednesday 19 October 2005

- ↑ Martin Dillon Killer in Clowntown: Joe Doherty, the IRA and the Special Relationship, London: Hutchinson, 1992. p. xxvi.

- ↑ See David Miller, Don't Mention the War: Northern Ireland, Propaganda and the media, London: Pluto Press, 1994., p. 129-30

- ↑ Paul Foot (1989) Who Framed Colin Wallace? pp. 265/6.

- ↑ Robin Ramsay (1999) The Wilson plots, Variant, issue 8 Summer 1999

- ↑ For an account of Wallace's work in Ireland, in collaboration with Tugwell, see Liz Curtis, Propaganda War, pp. 118-24,229-74: on some of Wallace's admissions of abuse, See "Wilson, MI5 and the Rise of Thatcher."

- ↑ This correspondence, along with an analysis by Robin Ramsay of the letter that Wilkinson passed along as "interesting," is given in Lobster, no. 16 (Spring 1988).

- ↑ See Ibid.

- ↑ TELEVISION AND RADIO, The Guardian, 3 January 1987

- ↑ Richard Ingrams, The Observer, 30 September 1990, p.20

- ↑ details of the search used are as follows: All English Language News > (((paul wilkinson) AND (terrorism))) and DATE(>=[year]-01-01 and <=[year]-12-31)

- ↑ Gearty 1991: 14

- ↑ Wilkinson 1990: 27

- ↑ Miller, David, (1994), Don't Mention the War: Northern Ireland, Propaganda and the Media London: Pluto.