National Domestic Extremism Database: Resistance and legal challenges

This article is part of the Undercover Research Portal at PowerBase - investigating corporate and police spying on activists.

See Main page' on National Domestic Extremism Database

Following the discovery that a number of journalists were included on the National Domestic Extremism Database, the National Union of Journalists encouraged members to find out whether they were on it too, and supported the action of comedian and journalist Mark Thomas in his efforts to have his files deleted.[1]

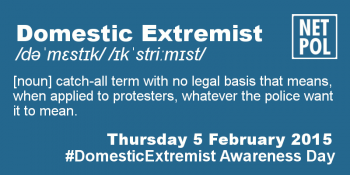

In 2014 the Network for Police Monitoring (Netpol) announced the campaign: "Don't Feed The Feds - Don't Be On a Database", encouraging people to assert their right not to end up on the domestic extremism database.[2][3]

This page is an overview of people who successfully accessed their files, and a list of related campaigns.

See also:

- National Domestic Extremism Unit for the history of relevant police units with ever-changing acronyms spying on activists.

- The Domestic Extremism page on the lack of a proper definition.

Spying on journalists

In 2014 it emerged that a number of journalists were recorded on the database,[4] following a series of Subject Access Requests. Fears that journalists were being targetted by police had been featured back in 2007,[5] and were highlighted again at the Kingsnorth Camp for Climate Action in 2008.[6] However, subject access requests showed that the history is much longer, some entries dated back to 2000 (as in the case of Jess Hurd)[7] and others had details of sexual orientation.[8]

All in all, there were over 2000 bits of information on the database relating to journalists.[9]

In protest, the National Union of Journalists has launched a court case on behalf of six of their members (two journalists, and four photographers).[10]

Metropolitan Police Commissioner Bernard Hogan-Howe responded that the police did not 'routinely collect' information on journalists and their sources, and that they only took an interest in peole if they were either victims or suspects.[11] However, he accepted that files on journalists who were not criminals should be destroyed.[12]

Legal Challenge: Andrew Wood

Andrew Wood is an anti-arms trade activist who attended a protest against the DSEI arms fair in 2005 and was photographed by police. His file shows the means the police used to learn his identity. When they eventually succeeded, they created a file on Mr. Wood even though he had never been arrested.[13] The police argued in court that the photographs were retained within the Public Order branch of the Metropolitan Police, where they would remain - the exemption being if they were to form part of a 'spotter card', which would be distributed only to FIT or Evidence Gatherer teams.

Following various appeals, the Supreme court ruled that Article 8 (right to respect for private life) of the European Convention on Human Rights had been engaged, and that the police had been wrong to keep the image once it was clear no offence had been committed.[14] Though the case does not mention the National Public Order Intelligence Unit, it set authority for its ability to retain such images, something that then parent organisation ACPO acknowledged in 2011.[15]

Legal Challenge: John Catt

John Catt was an anti-war protestor who had attended protests by SmashEDO against arms company EDO MBM Ltd in Brighton, and had learned that various details relating to him had been recorded on the National Domestic Extremism Database. He filed a case against ACPO and the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police. [16]

Catt argued that as someone without any convictions who was exercising his lawful right to protest his details should not be on the database in the first place. Their recording amounted to a breach of his Article 8 rights.

DCS Adrian Tudway, then National Coordinator Domestic Extremism, argued that it was necessary to retain them for the lifetime of the SmashEDO campaign:

- Mr. Tudway says that there is value to the police in knowing the identities of those who attend protests organised by Smash EDO and similar groups, even if they have not themselves been convicted of any offence. He accepts that in general only a small proportion of those attending protests of this kind resort to unlawful behaviour, but he nonetheless asserts that it is necessary for the police to retain information about potential witnesses and associates of those involved in unlawful activity for planning purpose and also for the purposes of eliminating law-abiding persons from the need for particular police attention.

Tudway also said that they needed to monitor Catt because he 'associates closely with violent members of Smash EDO and knowledge of this association is of intelligence value'.

The judges at the hearing said such general terms were not sufficient, and also that:

- ...we are left with the clear impression that police officers who attend protests organised by Smash EDO for the purpose of gathering intelligence record the names of any persons whom they can identify, regardless of the particular nature of their participation.

The police were ordered to delete Catt's details from the National Domestic Extremism Database as a violation of his human rights.[17] The Metropolitan police subsequently appealed the Court of Appeal March 2013 judgement, resulting in a three day hearing at the Supreme Court in December 2014.[18]

The Supreme Court handed down their judgement on 4 March 2015, finding in favour of the police's right to retain material acquired during surveillence of otherwise lawful protest.[19] The Network for Police Monitoring, which had made a submission to the case, in the wrote of the decision:[20]

- [The judgement] allows the police extraordinary discretion to obtain and retain the personal information of protesters whenever they consider it useful for purposes that are never fully defined, but that include investigating the ‘links between protest groups’ and their ‘organisation and leadership’. The Supreme Court has accepted that no further justification is apparently required.

We believe their judgement amounts to judicial approval for the mass surveillance of UK protest movements. It affirms the Metropolitan Police’s stated belief that anyone taking part in a public protest has no reasonable expectation of privacy.

Kevin Blowe of Netpol also stated:[21]

- This ruling allows the police extraordinary discretion to gather personal information of individuals for purposes that are never fully defined. The Supreme Court has accepted that no further justification is apparently required other than investigating the ‘links between protest groups’ and their ‘organisation and leadership’.

Netpol challenge

Though a number of people were able to access their files on the database, it appears that the Metropolitan police adopted a policy of neither confirming or denying that individuals and groups were on it.[22] In May 2013, The Network for Police Monitoring (Netpol) announced that they were seeking a judicial review[23] into the Metropolitan Police, claiming that they were systamtically failing to confirm to activists whether or not they were on the database, despite being required under the Data Protection Act. They also called on the Information Commissioner to to investigate and take action.[24] The judicial review is awaiting the judgement of the Supreme Court hearing in the case of John Catt (see above).[25]

Are you on the domestic extremism database?

Various political activists of different backgrounds made Subject Access Requests under the Data Protection Act and indeed received the information held on them. These records have shed considerable light on the extent of monitoring of activism by the police.

- Campaigner Linda Catt learned that footage of her protesting at the 2008 Labour Party conference was on the database and that her vehicle was being tracked by the ANPR system.[26] Much of these are likely to have been provided by the Forward Intelligence Teams which were a part of CO11.[27] Linda Catt's father John Catt, an anti-war campaigner with no crimal record was also on the NPOIU database which noted he had attend over 55 demonstrations, and detailing how he brought along his sketchpad to making drawings of the protests.[28]

- One activist learned of their place on the database when specifically targeted at a large event and pre-emptively arrested by police from the Met's Tactical Support Group. They subsequently overheard a conversation revealing they were a subject of interest to three separate police forces all of whom were to be called in the event of their arrest. Terms used to describe them at that point were later found on their file from the National Domestic Extremism Database.[29]

- Guy Taylor of the anti-capitalist group Globalise Resistance (targeted by undercover officer ' Simon Wellings'), learned that he was recorded at 27 different demonstrations between 2006-11, including those on opposition to the Iraq war and climate change. His Data Protection Act requests showed he was monitored at the Glastonbury music festival, where Globalise Resistance had a stall. It said the stall was selling political material of a 'XLW (extreme left wing) anti-capitalist nature', and that the police had gone to the Glastonbury staff to find out who from Globalise Resistance had asked for permission (which in this case was Taylor).[28]

- In 2014 Kevin Blowe, of police monitoring groups Newham Police Monitors and NetPol, obtained his domestic extremism database file and learned that he had been the subject of extensive recording of his attendance at various public meetings – all, as he put it, within the 'normal democratic process'. The file attributed various non-existent but apparently formal positions in campaigning organisations to him (such as 'Security Advisor' to the Counter Olympics Network), and contained details of his employer. When he reported criminal damage to his home, the Metropolitan Police forwarded his address and phone numbers to the NDEU database. The file also contained the entry: "there is no suggest that BLOWE has actively engaged in any Direct Action' but 'takes up many forms of left-wing activism'.[30]

- Green Party Jenny Jones (Baroness Jones of Moulscombe), a former member of the Metropolitan Police Authority and subsequently a Deputy Chair of the London Assembly's Police and Crime Committee, revealed in June 2014 that she too was on the domestic extremism database.[31] Her file indicated that she had been monitored for 11 years, and included tweets about possible police tactics for pro-cycling rally (London 'Critical Mass'), a 2007 Stop the War rally, details of public meetings she had addressed on public violence following the death of Ian Tomlinson at the hands of the police in 2009 and an anti-GMO protest in 2012.[32] An excerpt from her file is available here, and her questioning of Metropolitan Police Deputy Commissioner Craig Mackay and London Deputy Mayor Stephen Greenhalgh about her file here.

- In January 2016 The Guardian revealed that a whistleblower from the Domestic Extremism unit, DS David Williams, had written a letter to Jenny Jones, deputy chair of the body overseeing the Metropolitan Police. In it he stated that the unit had been involved in a systemic destruction of records as part of an illegal cover up to suppress the extent to which they had been spying on her.[33]

- Another Green Party member, Councillor Ian Driver, discovered that his file logged 22 occasions when he had helped organising meetings and demonstrations in relation to animal rights and gay marriage between June 2011 and June 2013.[34] A copy of Ian Driver's report is available is here.

- Mark Thomas, a comedian, activist and journalist discovered in 2013 he had been monitored since 1999 and his file included his activities as a journalist working with Channel 4, and his engagement with the police over a programme on the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act.[35] In 2014 he performed a comedy tour focusing on his including on the database and being spied upon.[36]

- Times journalist Jules Matteson discovered that data kept in his file included: "pocket litter" found during a search, sexual orientation, known/past addresses, phone numbers, old freelance clients, every time he was a crime victim or witness, his childhood, college, his father's work and a family member’s medical history from an unknown source.

Campaigns

- Subject Access Requests – an introduction, a guide from Netpol on making a Subject Access Request to the domestic extremism database.

Notes

- ↑ UK: Files on politicians, journalists and peace protestors held by police in "domestic extremist" database, Statewatch News Online, November 2013, accessed 10 September 2014.

- ↑ Don't Feed The Feds - Don't Be On a Database, Network for Police Monitoring, undated, accessed 10 September 2014.

- ↑ CALL OUT: Help Netpol’s legal challenge of secret police databases, The Network for Police Monitoring, 11 March 2014, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Dominic Ponsford, Six journalists challenge Met Police over surveillance and intelligence files kept on Domestic Extremism database, Press Gazette, 20 November 2014, accessed 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Jason N. Parkinson, When police spy on journalists like me, freedom is at risk , The Guardian, 21 November 2014, accessed 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Paul Lewis & Marc Vallée, Revealed: police databank on thousands of protesters, The Guardian, 6 March 2009, accessed 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Jess Hurd, My Life as a domestic extremist, JessHurd.com, 21 November 2014, accessed 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Jules Matteson, Met's journalist files include details of sexual orientation, childhood and family medical history, Press Gazette, 21 November 2014, accessed 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Jules Matteson, Journalists named on secret files, police admit, The Times, 11 November 2014, accessed 27 January 2015.

- ↑ NUJ members under police surveillance mount collective legal challenge, National Union of Journalists, 20 November 2014, accessed 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Rob Evans, Police face legal action for snooping on journalists, The Guardian, 20 November 2014, accessed 27 January 2015.

- ↑ William Turvill, Met chief Hogan Howe agrees files on journalists should be destroyed 'unless they are a criminal', Press Gazette, 24 November 2014, accessed 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Andrew Wood, Let's stay vigilant against Big Brother, The Guardian, 21 May 2009, accessed 10 September 2014.

- ↑ Judgement in the case of Wood v Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis, Supreme Court of Judicature, 21 May 2009, accessed 10 September 2014.

- ↑ National Co-ordinator Domestic Extremism, Frequently Asked Questions, Association of Chief Police Officers, undated (internal evidence indicates it was modified around 2011), archived by Undercover Research Group.

- ↑ Judgement in the case of John Oldroyd Catt v (1) The Assocation of Chief Police Officers of England, Wales and Northern Ireland and (2) Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis , Court of Appeal (Civil Division), 14 March 2013, accessed 10 September 2014.

- ↑ Rob Evans, Paul Lewis & Owen Bowcott, Protester wins surveillance database fight, The Guardian, 14 March 2013, accessed 10 September 2014.

- ↑ Day 2 of the John Catt ‘domestic extremism’ Supreme Court hearing, The Network for Police Monitoring (Netpol), 2 December 2014, accessed 15 January 2015.

- ↑ The Supreme Court, Judgment in case of Catt v Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis & ors, 2015 UKSC 9, releaesd 4 March 2015 (accessed 4 March 2015).

- ↑ Network for Police Monitoring, Supreme Court grants “judicial approval for the mass surveillance of UK protest movements”, 4 March 2015 (accessed 4 March 2015).

- ↑ Leigh Day Solicitors, Civil liberties campaigners claim Supreme Court judgment gives Police ‘extraordinary discretion’ to compile database, 4 March 2015 (accessed 4 March 2015).

- ↑ Dave Smith, Blacklisting: this looks like another British establishment cover-up, The Guardian, 11 November 2014, accessed 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Rob Evan & Owen Bowcott, Police face legal challenge over secret files on protesters, The Guardian, 18 October 2013.

- ↑ Netpol calls for formal investigation over access to secret police files on protesters, The Network for Police Monitoring, 19 May 2014, accessed 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Campaigners intervene in 'unlawful' police database Supreme Court case (press release), Leigh Day Solicitors, 1 December 2014, accessed 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Eco anarchists: A new breed of terrorist? Police forces challenged over files held on law-abiding protesters, The Guardian, 26 October 2009, accessed 5 September 2014.

- ↑ Undercover police work revealed by phone blunder, BBC News Online, 25 March 2011, accessed 10 September 2014.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Rob Evans and Paul Lewis, Glastonbury festival: how police spied on political campaigners, The Guardian, 15 July 2012, accessed 10 September 2014.

- ↑ Personal communication.

- ↑ Kevin Blowe, Secret Diary of an Olympic Domestic Extremist, Random Blowe blog, 5 February 2014, accessed 24 June 2014.

- ↑ The police’s secret surveillance of elected politicians with no criminal record is scandalous, The Green Party (press release), 16 June 2014, accessed 10 September 2014.

- ↑ Green Party politician Jenny Jones on 'domestic extremist' database, BBC News Online, 16 June 2014, accessed 10 September 2014.

- ↑ Rob Evans, Officer claims Met police improperly destroyed files on Green party peer, The Guardian, 8 January 2016 (accessed 8 January 2016).

- ↑ Rob Evans & Owen Bowcott, Green party peer put on database of 'extremists' after police surveillance, The Guardian, 15 June 2014, accessed 10 September 2014.

- ↑ Mark Thomas, Help the NUJ expose the monitoring of journalists, National Union of Journalists, 20 November 2013, accessed 10 September.

- ↑ MarkThomas.info, Cuckooed, accessed 10 September 2014.