Bernard Renouf "Johnny" Johnston

Lt.-Col. Bernard Renouf "Johnny" Johnston (died 23 March 2009, aged 88[1]) was a British Army officer[2] and in the late 1960s and early 1970s one of the British military's leading experts on psyops. After retiring from the British Army in 1975 he worked in PR for the Hong Kong government.

Background

Johnston had two brothers, Reginald and Gilbert, and a sister Dorothy. He was educated at Tonbridge School in Kent from 1934 to 1938.[3]

Army career

He served in the 48th Royal Tank Regiment from 1939-41, and in the Royal Armoured Corps from 1941-47.[4] He received an emergency commission as a 2nd Lieutenant on 21 March 1942.[5]

Johnston was awarded the MBE in 1947 "in recognition of gallant and distinguished services in the Netherlands East Indies prior to 30th November, 1946." The London Gazette listed his serial number as 229192.[6]

From 1948 to 1975 he served in the 7th Royal Tank Regiment.[7] He was promoted to the substantive rank of captain in 1948.[8] He was promoted to Major on 14 February 1955.[9] He was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel on 31 December 1966.[10] Johnston was appointed to the special list on 10 January 1971.[11] Johnston retired from the Army on 1 April 1975.[12]

Psyops

Johnston was involved in psyops training at the Joint Warfare Establishment at Old Sarum from around August 1968 to October 1970.

Part of Johnson's statement (given anonymously as INQ 1873) to the Bloody Sunday Inquiry was redacted to protect his identity. However a passage from this was read into the record of the inquiry with the assent of INQ 1873. This stated that:

- In April 1968 I was sent to the United States military base at Fort Bragg in North Carolina to attend a four-month course at the special warfare school. I then spent two years as an instructor at the joint warfare establishment at Old Sarum Wiltshire, and from there went directly to Northern Ireland.[13]

INQ 1873 told the Inquiry that "hardly anything" in the Fort Bragg course had a bearing on events in the North of Ireland:

- It was the American Army's activities in the Psychological Operations field, but at that time it was heavily orientated to Vietnam. In fact it was mainly all about activities in Vietnam.[14]

A statement by Maurice Tugwell to the inquiry confirmed that INQ 1873 'had been the head of the Army Psychological Operations branch at the Joint Warfare Establishment at Old Sarum' and 'a PsyOps specialist.'[15]

According to INQ 1873, the PsyOps staff at Old Sarum consisted of only two people, himself and an assistant.[16]

Ireland

The McGurk's Bar Massacre campaign has named Johnston as INQ 1873, an anonymous witness who testified to the Bloody Sunday Inquiry.[17] As will be seen below, the correspondence between INQ 1873's statement and prior accounts of Johnston's career in Ireland suggest this is correct.

July 1970 visit

INQ 1873 visited Northern Ireland on 15-17 July 1970 shortly after the Falls Curfew, while serving as GSO I (PSYOPS) JWE. He met with staff officers at HQNI, R Burroughs, the UK Government Representative in Northern Ireland, and Tom Roberts - Deputy Director of Information, Government Information Services.[18]

In his report on the visit, INQ 1873 made the following recommendations:

- a. The feasibility of setting [up] a radio station on the lines of a Forces Broadcasting Station be examined.

- b. The feasibility of establishing a committee for the co-ordination of psyops activities and for dissemination of information be established.

- c. A Psyops Staff Officer is placed on call to HQ Northern Ireland, and will visit HQNI periodically.

- d. An examination is made on the effectiveness of current left wing propaganda activities.

- e. PR should be more active and positive wherever possible.[19]

Information Liaison Department

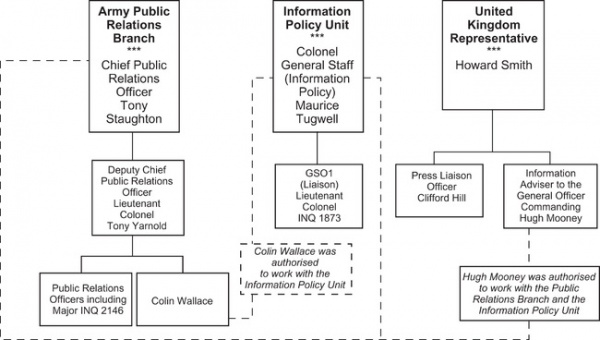

According to Paul Foot in his book Who Framed Colin Wallace 'a new unit' in Army HQ in Northern Ireland in 1970 called 'Information Liaison - later Information Policy' was 'commanded by a military officer with the rank of lieutenant colonel.' 'The first of these', reported Foot, 'was Lieutenant Colonel Johnny Johnston'.[20]

According to the Bloody Sunday Inquiry:

- Lieutenant Colonel INQ 1873 was sent to Northern Ireland in October 1970 in order to run the Information Liaison Department. He was an expert in psyops in combat situations and was responsible for psyops in Northern Ireland under the direction of the Commander Land Forces (CLF).[21]

INQ 1873 worked on his own under the Chief of Staff until the arrival of Col. Maurice Tugwell later in 1971. He told the Inquiry that he had an agreement with "Mr Staunton of the Public Relations section", probably Tony Staughton that he would not talk to journalists without informing him.[22]

- If the GOC was not available, some editors or journalists were referred to me. I recall briefing Mr William Deedes (now Lord Deedes) who I think had recently resumed his journalistic career, and the late Mr T E (Peter) Uttley, both as it happened from The Daily Telegraph. There were others but I do not recall who they were. I sometimes spoke to some people from the community, some trade union officials for example the trade unions in the 1970s were, or did their best to be, nonsectarian.[23]

Role of PsyOps

In his initial statement to the Inquiry, INQ 1873 denied any involvement in Psyops in Ireland:

- I am aware that the term Psychological Operations (Psyops) was sometimes used loosely in a general context but it is an emotive term and misunderstood. There is a principle that psychological operations may not be conducted against one's own people. That principle was adhered to in the Army's operations and activities in Northern Ireland, certainly during the time I was there - I left in June 1972. The IRA was not considered an enemy in the context of a war and the Republican Movement generally was not the subject of any psychological operations because, as I say, it was expressly forbidden - the citizens of Northern Ireland were 'our own people' and that included the IRA.[24]

INQ 1872 backtracked on this statement in his oral evidence to the inquiry, saying: "Depending on definition, that statement should be amended, after a year of thinking."[25]

According to Hugh Mooney, INQ 1873 engaged in low-level psyops with the assistance of Colin Wallace. These included distributing leaflets, arranging for officers' wives to write to newspapers, and writing anonymous letters to Private Eye. INQ 1873 also used the HQNI printing press to forge press cards for army photographers. Mooney assumed that this activity was authorised by Lt Gen Harry Tuzo or Maj Gen Anthony Farrar-Hockley. Although, Mooney shared an office with INQ 1873, he told the Bloody Sunday Inquiry he was not involved in these operations and regarded them as ineffectual.[26]

INQ 1873 was questioned on this psyops activity at the Saville Inquiry:

- Q. Can you give us any examples of the sort of work that you have in mind?

- A. Mine was entirely on a low level, and I stress for a low level. That is perhaps anonymous letters to newspapers only, not to individuals; occasionally a change in documents or forging documents; by that I mean copying documents and making them appear to be otherwise than what they are.

- Q. Stopping you there for a moment, would that involve disseminating information that was in itself untrue?

- A. Not as a general -- not as a general distribution, no.

- Q. What would be the point of forging a document?

- A. If one wanted to convey a message to a particular group, you can make it appear as if it was coming from somebody else.

- Q. Would the information contained in that document, generally, to your knowledge, be true?

- A. Depending on circumstances, ma'am.[27]

Later in his evidence, INQ 1873 took issue with Mooney's account of his role:

- The instance Mr Mooney quotes, he quotes the Times and the Private Eye, I did not do those.

- Q. You did not do those?

- A. No. The only ones were to Irish newspapers, Northern Irish newspapers, and there were not many of those.

- There are, at the most, half a dozen, or six, over a period of six months.[28]

According to INQ 1873's evidence, such psychological operations came to an end in about July 1971.[29]

INQ 1873 took part in a meeting recounted by John Rayner on 8 June 1971:

- Major General Farrar-Hockley called in Lt.Colonel [redacted - INQ 1873] his Psy-Ops expert, who had already prepared a list of offending articles with cuttings, and I went over these with Colonel [INQ 1873] afterwards. Mr Mooney will take them as a basis for discussion with Colonel INQ 1873 today.[30]

Under cross-examination Hugh Mooney stated that INQ 1873:

- was conducting PsyOps against and within the population of Northern Ireland, of course. [31]

PsyOps Committee

In a paper for a meeting on 21 July 1971, INQ 1873 proposed the creation of a psychological operations staff at Headquarters Northern Ireland under the direction of a Psyops Committee, with a working committee handling day-to-day operations.[32] This included the following terms of reference for his own position:

- The GSO 1 (Liaison) is to be responsible for:

- a. Advice on psyops to commanders and staff in Northern Ireland.

- b. Psyops activities in support of the Security Forces against extremist groups in Northern Ireland.

- c. Assistance, as required, with the dissemination of information and publicity matters generally.

- d. Co-ordination as necessary with other forces and agencies, including the RUC, when implementing psyops activities.[33]

Asked at the Saville Inquiry as to why a meeting which included such high ranking figures was not minuted INQ 1873 simply stated "I cannot explain." [34]

INQ 1873 told the Bloody Sunday Inquiry that there was a meeting to discuss this document in July 1971. Those present would have included the Commander Land Forces, the Chief of Staff and INQ 1873 himself, as well as a civil representative, probably from the office of the UK Representative in Northern Ireland.[35] He said that although there was no record of meeting, it concluded a PsyOps Committee was not necessary.[36]

Under cross-examination at the Saville Inquiry INQ 1873 gave a highly evasive response to the question as to whether the committee had in fact been set up contrary to his earlier claim:

- Q. Could it be that there was a committee set up but, in order to make sure that it was deniable, no records were kept, or at least no records made available to this tribunal?

- A. I do not think that there was a record of that meeting."

At another point during cross-examination INQ 1873 gave the following response to a question regarding the proposed committee:

- Q. My next question is do you know whether it [the psyop committee] was actually ever set up?

- A. I do not, and - I just do not know, I do not know."[37]

INQ 1873 was then asked whether the PsyOps committee had emerged in another form:

- Q. You know that it appears from this document that the term "PsyOps" was never to be used, or should not be used, because of its sinister implications. Could it be that the committee that was set up was called the Military Information Policy Committee?

- A. It may have devolved from that.

- Q. It may have devolved from that?

- A. Yes.[38]

INQ 1873 and Maurice Tugwell both testified to the Saville Inquiry that the Psyops Committee proposal was abandoned without ever having met.[39]

- Hugh Mooney said that he did not recall attending a meeting of the Psyops Committee and was “totally puzzled ” by references to the committee. In a report of unknown date written after mid-July 1971 but before Colonel Tugwell’s arrival, Hugh Mooney said that he was a member of a psyops working committee that had recently been set up. It is unclear whether that committee ever met at all. The Working Committee proposed in July 1971 was to have four members. Hugh Mooney’s recollection was that he and Colonel INQ 1873 were the sole members of any psyops committees and that they met informally.[40]

INQ 1873 testified that at the time he drew op the Psyops committee proposal "I did not know of Colonel Tugwell's appointment. I had been tasked to do this and to produce this paper."[41] He also said that Tugwell reinforced a policy of winding down psychological operations.[42]

Information Policy Unit

In September 1971, the Information Liaison Department was replaced by the Information Policy Unit under Col. Maurice Tugwell. INQ1873 was appointed as his deputy.[43]

A new Military Information Policy Committee met on 17 November 1971, and agreed the terms of reference for a Military Information Working Party. INQ 1873's position as GSO I Liaison carried membership of the latter.[44]

A draft paper prepared by Charles Henn of DS10 on 30 November 1971, described the role of the GSO 1 (Liason) as encompassing psychological operations.[45]

At the bloody sunday inquiry INQ 1873 confirmed that his initial official title in Northern Ireland was "Psyops Staff Officer" later changed to GS01 Liaison (presumably in order to furnish deniability regarding the execution of PsyOps in Northern Ireland and that he was known as Major General Farrar Hockley's PsyOps expert. [46]

Under cross-examination at the Saville Inquiry, INQ 1873 said that this document was "misleading" adding that "The organisation, such as my post, were kept in case a situation developed when it might be necessary to consider use of further Psyops."[47]

Col Tugwell also testified to the Inquiry in relation to INQ 1873's Psyops work:

- by January 1972 I think his work in that department had run right down. He had become my deputy; he did an awful lot of research; went through all the newspapers and things and analysed hostile propaganda for me; he was an archivist as well.[48]

Diary entries prior to Bloody Sunday

In his diary for 2 January 1972, INQ 1873 wrote:

- Went up to the Ops Room to find CLF there, ruminating on the Pat Arrowsmith leaflet and looking at 39 Brigade's disposition for CRA marches. These are a distinct challenge to authority and the organisers want a fracas to store up more hate against the Army.[49]

The entry for 3 January read:

- Had hoped to spend the whole working day at 39 Brigade study period, but had to finalise our latest review of information before typing, so did not get there until 11.15, only to find I was just too late. However, joined them at lunch in the mess. Afterwards listen to [name redacted] QO Highlanders Speaking about rehabilitation Of Ballymacarett, Derek Wilford on community relations and finally Maurice T on information. Latter V staccato, but best address was from GOC, who spoke about behaviour, image and need to be aware of public opinion.[50]

On 5 January he wrote:

- Meeting of DOPs occupied the well-paid help most of the morning. Lunched in the office. In the afternoon a meeting, first of all reviewing information situation. Discussed preparation of booklets and pamphlets. All good stuff but an organisation is needed to do it.[51]

INQ 1873 told the Saville Inquiry that one of the leaflets then being contemplated was called "Terror and Tears."[52]

On 11 January, he wrote:

- "I devoted the day primarily to preparing case studies of two Republican examples of propaganda, the first dealing with the unreal claim for position of Catholics and the second that of the attempt to confuse responsibility for McGurk's bar on 4th December last.[53]

On 13 January he wrote:

- Nearly 50 men were arrested last night, most of them in Belfast by 39 Brigade. The IRA are definitely taking a knock but the problem with juveniles and women increases. Today's Republican papers reflect the continuing propaganda offensive. The Irish News centre pages carry articles and letters which are completely anti-Army or anti-Government. The usual weekly meeting at 10 am, which was mainly waffle, so different in the days of FH.[54]

On 16 January, he wrote:

- Spent the afternoon and evening writing the first draft of the lecture on Military Information Policy whilst the rain pelted down outside. In the evening, went up to the office to write the End of Play summary for MoD. Quite a lot to include. [Name redacted] arrest in Dundalk. Cox's forestalling article about 1 Para among them.[55]

The "Cox's forestalling article" referred to was a story by Richard Cox in the Daily Telegraph of 14 January 1972, which accused Irish reporters of trying to alienate soldiers of other regiments from 1st Battalion the Parachute Regiment.[56]

On 22 January, INQ 1873 wrote:

- In the meantime trouble was brewing at Armagh, which seems to have been contained. Much more serious is the demonstration at Magilligan where TV showed soldiers firing rubber bullets almost point blank into crowds."[57]

On the following day, 23 January, he wrote:

- As I feared Magilligan is by far the most serious. 8 Brigade seem incapable of getting any operation right and there seems to have been antagonism between the Royal Green Jackets and the Paras. At any rate the result was that 1 Para platoon cut up rough and might well have put all the work of the information services back seriously.[58]

On 25 January, he wrote:

- Simon Winchester's article in the Guardian this morning has set the boat rocking with the allegations about 1 Para. Incidentally, the [Court of Inquiry] has revealed some of the behind the scenes disagreements between 8th and 39th Brigade.[59]

The Guardian article referred to, "Army call to bar Paratroops", was actually by Simon Hoggart.[60]

On 26 January He wrote:

- The morning and afternoon were taken up almost entirely with the Winchester/Hoggart case. Hoggart has now left Northern Ireland. MoD wanted ammunition to fix Winchester, but had to tell them not on, insufficient grounds.[61]

Bloody Sunday

INQ 1873 was the editor of the Military Information Working Party review which covered the period between 30th December 1971 and 31st March 1972. He believed that Hugh Mooney also worked on the review and that Colonel Tugwell might have seen early drafts.[62]

The review contained the following sentence:

- When intelligence indicated that the IRA planned to use the march as cover for their gunmen, consideration was given to various pre-emptive and protective measures in the propaganda field.[63]

However, INQ 1873 told the Saville Inquiry that intelligence was not available to the Information Policy Unit ahead of the march.

- It was drafted, of course, at the end of March, when a lot had really come out in what information was available and what intelligence was available and it looks to me as if I was not clear in my mind when writing between what we knew at the end of March and what we knew at the end on the end of January.[64]

INQ 1873 nevertheless told the Saville Inquiry that pre-emptive propaganda measures had been taken:

- The pre-emptive consisted of a warning put out through the media of the march and the results that might come from it in the way of disorder.[65]

This was a joint Army-RUC statement, issued on 28 January 1972, which concluded:

- Experience this year has already shown that attempted marches often end in violence that must have been foreseen by the organizers, and clearly the responsibility for this violence and the consequences of it must rest fairly and squarely on the shoulders of those who encourage people to break the law.[66]

INQ 1873 told the Inquiry that Col Tugwell had suggested he observe the march, but that he had been unable to to get transport that weekend.[67]

- I spent the morning in my office, making two or three visits to the operations room to check on events. I returned to my home for lunch. On learning of the shootings I went to the operations room for a while and having no specific role decided to watch events unfold on the television at home, making sure that the operations room staff knew where I could be contacted if I was wanted. My quarter was a hiring close by the Headquarters. I recall making one visit to the operations room during the evening.[68]

In his diary for that day, 30 January, INQ 1873 wrote:

- A very significant and tragic day. At the 10.00 BBC news the casualties were given as 13 dead, 17 injured and 50 arrested. Already the opposition are talking of Britain's Sharpeville. One wonders if the truth will ever be sorted out. Undoubtedly there was an IRA plan for the hooligans to promote trouble. This succeeded and, as 1 Para went in, the gunmen opened up, even to the extent of firing into their own people."[69]

The day after Bloody Sunday, INQ 1873 travelled to Derry with Colin Wallace. At some point on that day, General Ford told him to "Get that on the front page", in reference to the previous day's events.[70]

Diary entries following Bloody Sunday

On 31 January, INQ 1873 wrote:

On 1 February, INQ 1873 attended "the weekly intelligence meeting, interrupted by a briefing". This was chaired by the Colonel GS Int, know to the Bloody Sunday Inquiry by the cipher INQ 2241.[73]

On 7 February, he wrote:

- I believe NICRA have acquired for themselves an image of 'respectability' but it remains to be seen if 17 the Bradys allow them to keep it.[74]

'The Bradys' was a reference to the Provisional IRA.[75]

On 13 February, he wrote:

- The morning passed, reading the papers and listening to Colin Wallace's account of some of the deliberate fabrications that have been made by the Catholics in Derry over the shootings of 30th January.[76] We all doubt whether the Chief Justice Tribunal will be equal to the mendacious Irish.[77]

On 23 February, he wrote:

- All papers except the biassed Irish News full of yesterday's IRA explosion at 16 Para Bde HQ officers' mess. An appalling act which shows the Irish at their worst - violent cold-blooded killers.[78]

On 29 February he wrote:

- Some how the morning again disappeared much of it absorbed by briefing 1 Kings [redacted] and 4 Regt RA. Audience most interested in the "information" war. In the afternoon, up to Stormont where had first copy of "Terror and Tears". People depressed about Widgery Tribunal but in fact it is going quite well.[79]

On 5 March, he wrote:

- I went to the Ops Room at 5 pm to check that photographic coverage of CR marches was okay.[80]

Old Sarum Psyops lecture

According to Peter Watson, Johnston gave a talk on Psyops at a course held on 14-18 February 1972:

- Lt-Col. B. R. Johnston, Britain's foremost psywar expert, distinguishes three phases of an insurgency, according to a classified talk which he gave at the Joint Warfare Establishment at Old Sarum. The first of these is the identification and isolation of hostile elements; the second, he says, is the elimination of the rebel elements and the projection of a favourable image of the British forces; and the third is the consolidation of these gains, negotiation towards amnesty, and the winding down of hostilities. Active psywar comes in at the end of phase one. At the time of this talk (1972), the war in Northern Ireland was in phase two, according to Johnston.[81]

INQ 1873 was asked about his return to Old Sarum at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry:

- A. I had gone back to Old Sarum to deliver some lectures.

- Q. About your continuing PsyOps work in Northern Ireland, perhaps?

- A. No. I went back to deliver lectures on certain case studies which were familiar to me, which did not concern Northern Ireland.[82]

Part of INQ 1873's diary for 16 February appeared to read:

- All the Psyops staff assembled - probably first time ever. [Redacted] and [redacted] on he course! In the afternoon ran through studies for Anguilla and Indonesia which seemed alright so long as the power supply lasts.[83]

His diary for 17 February read in part:

- delivered "Anguilla" to a rather cool audience from 9 to 10. Only 13 on the course, mostly NATO, so reaction is not surprising. Spent the rest of the morning talking to [redacted] and [redacted] about conditions in N. Ireland. Everyone is interested in what's going on and all felt our PR is not good enough but cannot make any realistic suggestions when challenged.[84]

His diary for 18 February read in part:

- at 9am did "Indonesia". It went down quite well, but the course was not a very lively one and one didn't get much out of them. Sat in on [redacted] but left question-time to ring Lisburn to see that all was well in the office and in the mess. After lunch I lecture on the Urban Guerilla but it still not a satisfactory lecture & must be re-cast again.[85]

Hong Kong

Johnston headed the Hong Kong government's Information Services Department from 9 June 1979 to 31 December 1979 as Acting Director of Information Services.[86]

In his memoir of the department, Moss describes Johnston's time in charge as follows:

- The man who took over from Slimming, in an acting capacity until Bob Sun's return to the department as DIS on January 1, 1980, was Bernard Renouf Johnston, better known as 'Johnny'. Already thoroughly familiar with the [Vietnamese] refugees issue, Johnston organised special documentary films, booklets and information kits designed to highlight the burden posed for an already overcrowded territory that was not receiving the co-operation it needed from countries far better equipped to share the load. Though he often personally organised briefings and conducted tours of improvised refugee centres, Johnston also busied himself with other departmental priorities, including the importance he attached to recreational events organised by the staff club. For relaxation he embarked on weekend excursions to the New Territories and outlying islands with his wife Gwyneth, a noted authority on butterflies who succeeded in rearing lesser-known species in a special room assigned for the purpose in their government quarters in Mount Austin Road. Together they collaborated on a book on Hong Kong butterflies, published by ISD.[87]

Johnston was still working as Deputy Director of the Department in 1984.[88]

Saville Inquiry

Missing diary entries

INQ 1873 gave an initial statement to the Saville Inquiry on 7 November 2001. This stated that "I kept a personal diary but it does not assist much with these events as, for obvious reasons, I was circumspect about what I wrote."[89]

After the Deputy Solicitor of the Inquiry requested to see this diary, INQ 1873 gave a supplementary statement on 9 September 2002. This stated that he had not kept a diary in 1971, because he had finished a 5-year diary in 1970, and had not been keeping a new one until 1972.[90]

- I have reviewed the entries for 1972 in my diary. I left Northern Ireland on 9 June, so the only relevant entries are those from 1 January to 9 June 1972. I do not believe that there is anything in those entries which will assist the Tribunal. I am however content that the Inquiry should not have to rely on my assessment of relevance, and I attach a copy of the entries from 1 January 1972 to 9 June 1972 inclusive.

- It will be seen that some of the entries are missing. Although I cannot be absolutely certain, I believe that the explanation for this is as follows. In late 1971 my mother became unwell and as a result a dispute arose between me and my sister. I believe that I may have made entries in my diary on subsequent years which, when I reread them some years later, I realised were both unfair and hurtful to my sister. I was concerned that if I died suddenly my sister might read the diaries and be upset by the entries. I believe I therefore tore them out.

- I do not believe that any of the entries were torn out because of anything in them to do with my service in Northern Ireland, let alone anything to do with the events of 30 January 1972.[91]

Last years

Johnston died on the 23 March 2009, aged 88.[92]

Notes

- ↑ To the Green Fields, The Royal Tank Regiment Association, accessed 12 June 2010.

- ↑ To the Green Fields, The Royal Tank Regiment Association, accessed 12 June 2010.

- ↑ Old Tonbridgian News, August 2009, p.15, Old Tonbridgian Society.

- ↑ To the Green Fields, The Royal Tank Regiment Association, accessed 12 June 2010.

- ↑ SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 3 APRIL, 1942, issue 35509, p. 1498.

- ↑ SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 26 JUNE, 1947 (pdf), issue 37996, p.2922.

- ↑ To the Green Fields, The Royal Tank Regiment Association, accessed 12 June 2010.

- ↑ SECOND SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette Of TUESDAY, the 2nd of MARCH, 1948, issue 38226, p.1617.

- ↑ SECOND SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette OF FRIDAY, 18th FEBRUARY, 1955, issue 40412, p. 1083.

- ↑ SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 10TH JANUARY 1967, issue 44223, p.307.

- ↑ SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 12TH JANUARY 1971, issue 45278, p. 382.

- ↑ SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 15TH APRIL 1975, issue 46542, p.4814.

- ↑ Bloody Sunday Inquiry Transcript, Wednesday, 2nd October 2002 (9.35 am), Examination of Col. INQ 1873, pp.49-50

- ↑ Bloody Sunday Inquiry Transcript, Wednesday, 2nd October 2002 (9.35 am), Examination of Col. INQ 1873, p.81

- ↑ British Irish Rights Watch, BLOODY SUNDAY INQUIRY Week 67

- ↑ Day 242, p.54, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ INQ 1873 Unmasked, The McGurks Bar Massacre, 18 June 2010.

- ↑ C1873 - Statement Of INQ 1873 (pdf) Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 24 March 2003.

- ↑ C1873 - Statement Of INQ 1873 (pdf) Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 24 March 2003.

- ↑ Paul Foot Who Framed Colin Wallace?, 1989 London: Macmillan, p. 16.

- ↑ Psyops and military information activity, Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry - Volume IX - Chapter 178, 15 June 2010.

- ↑ Statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, accessed 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, accessed 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, accessed 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Day 242, P.3., Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Statement of Hugh Mooney, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Day 242, page 4, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.54, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ day 242, pp.4-5, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Statement of Hugh Mooney, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Hugh Mooney Hugh Mooney under cross examination at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002 Pg. 102. Accessed 6 April 2014

- ↑ Statement of Hugh Mooney, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Statement of Hugh Mooney, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 21 June 2010.

- ↑ INQ1873 under cross examination at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002 Pg. 056. Accessed 5 April 2014

- ↑ Day 242, pp.56-57, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, pp.56-57, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ INQ1873 under cross examination at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 26 September 2002 Pg. 89. Accessed 23 February 2014

- ↑ Day 242, p.61, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Psyops and military information activity, Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry - Volume IX - Chapter 178, 15 June 2010.

- ↑ Psyops and military information activity, Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry - Volume IX - Chapter 178, 15 June 2010.

- ↑ day 242, pp.12-13, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ day 242, pp.4-5, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Psyops and military information activity, Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry - Volume IX - Chapter 178, 15 June 2010.

- ↑ MILITARY INFORMATION POLICY COMMITTEE AND WORKING PARTY - COMPOSITION AND TERMS OF REFERENCE, 17 November 1971, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, accessed 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Organisation of Information Activity for Northern Ireland, 30 November 1971, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, accessed 21 June 2010.

- ↑ INQ1873 under cross examination at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002 Pg. 055. Accessed 5 April 2014

- ↑ Day 242, pp.64-65, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 240, p.77, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 30 September 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.28, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, pp.29-30, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, pp.30-31, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.31, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, pp.31-32, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, pp.32-33, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.34, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.35, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.35, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.37, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, pp.38-39, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.39, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, pp.40-41, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Psyops and military information activity, Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry - Volume IX - Chapter 178, 15 June 2010.

- ↑ Information Policy Working Party Review No 11, Lt Col GSO 1 Liaison, 3 April 1972.

- ↑ Day 242, p.23, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.24, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Joint Army RUC Statement Issued 28 January, 28 January 1972, Bloody Sunday Inquiry.

- ↑ Statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry], accessed 21 July 2010.

- ↑ Statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry], accessed 21 July 2010.

- ↑ Day 242, pp.41-42, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry], accessed 21 July 2010.

- ↑ Day 242, p.44, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.44, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, pp.45-46, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.46, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.46, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.47, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Day 242, p.67, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ 1873.23.1, attachment to statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, accessed 28 June 2010.

- ↑ 1873.23.3, attachment to statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, accessed 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Day 242, p.47, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ Peter Watson, The Military Uses and Abuses of Psychology, Penguin Books, 1980, p.290.

- ↑ Day 242, p.47, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002.

- ↑ 187.21.1, attachment to statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, accessed 28 June 2010.

- ↑ 187.21.2, attachment to statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, accessed 28 June 2010.

- ↑ 187.21.3, attachment to statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, accessed 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Peter Moss, Chapter 25: Gearing for the New Millenium, GIS through the Years, Government Information Centre, Hong Kong, accessed 14 June 2010.

- ↑ Peter Moss, Chapter 17: Profound and Lasting Consequences, GIS through the Years, Government Information Centre, Hong Kong, accessed 14 June 2010.

- ↑ The Bulletin, January 1984, p.47, Hong Kong Chamber of Commerce.

- ↑ Statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, accessed 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, accessed 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Statement of INQ 1873, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, accessed 21 June 2010.

- ↑ To the Green Fields, The Royal Tank Regiment Association, accessed 12 June 2010.