Hugh Mooney

Hugh Mooney was a member of the Foreign & Commonwealth Office’s Information Research Department (IRD).[2] He has also worked as a journalist, including as a sub-editor on the Irish Times.[1]

Middle East

As a Reuters Correspondent in the Middle East, Mooney spent six months in Aden in 1966, and reported on the Arab-Israeli War of 1967.[3]

Information Research Department

Mooney left BBC External Services in 1969 to join the IRD. By this time the Department's remit had been widened from fighting communism to countering all hostile propaganda.[3] Mooney told the Bloody Sunday Inquiry:

- For example I spent some weeks in Bermuda advising on countering black-power propaganda and during 1971, I started to visit Northern Ireland, where the Government of the Irish Republic had financed pro-republican propaganda.[3]

In his statement to the Bloody Sunday Inquiry Mooney described part of the IRD's brief as "to secure clearance of intelligence reports for exploitation in the press and elsewhere." [4] Mooney stated that heightened propaganda activity on the part of IRD and other agencies from 1971 onwards was in response to Major General Tony Farrar-Hockley (then Commander of Land Forces, Northern Ireland) informing the MOD that "the Army was losing the propaganda war."[5]

Northern Ireland

Mooney first visited Northern Ireland in March/April 1971 at the request of the UK Government Representative, Ronnie Buroughs.[3]

Mooney was seconded to the Home Office for the purpose of an appointment in Northern Ireland which he took up in June 1971.[1] He told the Bloody Sunday Inquiry:

- My brief was to assist the Army, the RUC and the Northern Ireland Government Information Service to counter hostile propaganda and improve their public relations activity.[3]

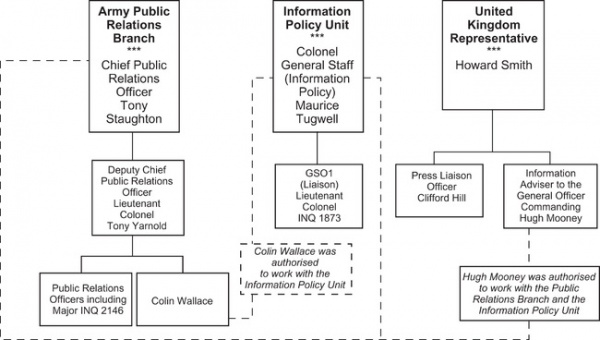

Mooney continued to work with the Army PR and Information Policy teams until the end of 1973.[6]

In a supplementary statement to the Saville inquiry Mooney claimed not to have been involved in psyops operations in Northern Ireland, though he confirmed that INQ 1873 was engaged in such activities. Mooney also claimed, contra Colin Wallace, that psyops were not considered significant in Whitehall. Mooney further stated that his only role regarding psyops was strictly limited: "My function in relation to any psyops activity was to keep an eye on what was going on and report to UKREP if necessary."[7]

In his statement Mooney also claimed that all psyop activity in NI ceased in 1971 as the emphasis was shifted to Public Relations techniques with the formation of the Information Policy Unit in September of that year. Mooney acknowledged that there had been discussion of the creation of a "counter-insurgency committee" which would have engaged in the formulation of Psyops operations, Mooney claimed that the committee was never created. Mooney was emphatic in his statement that IP was not engaged in psyops: "IP most definitely was not a psyops committee." [8] Although Mooney claimed that psyops in Northern Ireland came to an end around July of 1971 that was the same month in which INQ1873 drew up the proposals for the creation of a psyop committee. [9] INQ1873 confirmed the presence of the Commander Land Forces Northern Ireland, the chief of staff, and a representative of the UKREP at the meeting but claimed to be unsure as to whether or not the director of intelligence and the GS01 Intelligence were present at the meeting discussing the creation of the psyops committee. In spite of the senior personnel present at the meeting INQ1873 claimed that the meeting was not minuted.[10] Questioned as to whether IP might in fact have been (contrary to the firm assertion of Mooney) the realisation of the proposed psyops committee INQ1873 gave the following ambiguous response:

"Q. You know that it appears from this document that the term "PsyOps" was never to be used, or should not be used, because of its similar [damaging] implications. Could it be that the committee that was set up was called the Military Information Policy Committee? A. It may have devolved from that..." [11]

Through IP Mooney engaged in, as he described it, "briefing the non-resident press; providing unattributable briefing material for PR; introducing journalists to PR; helping improve procedures for the storage and exploitation of cuttings and other briefing material."[12] At the Saville Inquiry Colin Wallace provided a quite different description of IP's activities:

- Q. its [the Information Policy Unit] role was PsyOps?

- A. Yes, PsyOps is a very specific term. Basically it was disinformation or using information to influence either hostile or the local population...

- Q. Was black propaganda something in which the Information Policy Unit was ever involved?

- A. On a few occasions, but not often.[13]

As well as denying involvement in psyops Mooney denied the claim of Colin Wallace that he was Wallace's MI6 contact and denied ever working for British intelligence.[14] In spite of claiming to have had no direct involvement in Psyops Mooney acknowledged that he took part in an introductory course on Psyops at Old Sarum Wiltshere in February 1971 [15] Mooney's colleague INQ1873 spent two years at the Joint Warfare Establishment engaged in Psyops training at the same location prior to his assignment in Northern Ireland. Regarding INQ1873's activities in Northern Ireland Mooney stated that "the term "psyops was to be avoided and "liaison" was to be used by staff as the cover title for the branch and some work was to be overtly connected with community relations..." suggesting that at least some Psyops activity was directed at the civilian population of the six counties. [16] Mooney's comments regarding the rejection of a proposal for a "force's radio" station is also suggestive in this regard: "I do not know whether when this [the force's radio station proposal] was considered its value as a vehicle for propaganda directed at the local population was fully taken into account." [17]

Under questioning at the Saville Inquiry Colin Wallace stated that Mooney was a part of the "PsyOps team" whose other members included Wallace, Colonel Maurice Tugwell, and INQ1873. [18] Directed to Mooney's statement that he had not engaged in psyops activity in Northern Ireland Wallace responded: "It depends on his definition of PsyOps, but I would disagree totally." Responding to Mooney's claim that his activities in Northern Ireland were largely confined to using press briefings to improve the image of the Army Wallace stated that Mooney's chief activities were: "supplying information to discredit terrorists and left-wing groups." [19]

Mooney's claim to have been focussed largely on improving the public image of the Army is also contradicted by his own comments in 1971:

"My breifings [sic] concentrate on widening the split in the IRA and alienating the civil population from the terrorist."[20] Such activities included fomenting infighting amongst Republican groups by spreading false rumours of a plan by the Official IRA to assassinate the leadership of the provisionals:

"One briefing that I gave to CIC to form the basis of an article goes as follows: The Official IRA is getting increasingly concerned at the success of Provisional violence. The Officials are therefore seriously considering assassinating the dozen or so leading Provisionals in Belfast. The line taken is that the Officials [word redacted] allow a few fanatics to take over Ulster, thus thwarting the Officials' own plans for a communist takeover of democratic institutions and a working economy." [21]

In the same letter Mooney described his involvement in dirty tricks operations against the Provisionals:

"I hold frequent discussions with senior MOD PR officers on how to react to events so as to present the army in the best possible light and damage the IRA. For example, recently the IRA have started to use heavier weapons, including bazookas. We played down the significance of the weapons, stressing that it was obsolete. We were helped by the fact that the bazooka shells did not explode, because the safety cap was not removed. This latter fact was concealed. Instead a dummy army order was prepared which said such shells should be tested electrically. This would have the effect of exploding the shell in the tester's hands. Clearance is being sought for this scheme. When two young terrorists were killed while making a bomb, the story was put around that gelignite reacts to changes in temperature. We pointed out that the explosion took place on the coldest night of year. [sic] Subsequently, there were some very large explosions against soft targets, which led army experts to believe that the terrorists were getting rid of suspect stocks of gelignite. It was at one such meeting that I discussed with army how to handle the timing of the announcement that the IRA was using hunting ammunition and Dum Dum bullets." [22]

Mooney also referred to his involvement in the creation of the "Petition for Sanity" - a call for peace in Northern Ireland ostensibly created by the political pressure group, the New Ulster Movement [23]

"on the political side, I have... had some success with promoting the Petition for Sanity, which now has more than 20,000 signatures and plqns [sic] to hold peaceful demonstrations." [24]

Mooney's comments regarding the need to "reinforce" his "cover" suggests that Mooney was engaged in covert psyops but that he felt that a greater degree of deniability was required:

"My cover needs to be reinforced by giving me a separate office with my title on the door. Sharing a room with the psyops specialist has cast a slight cloud over my activities within HQNI. This new office should be within the secure area so that I can have access to more of the raw intelligence and liaise more closely with the Director of Intelligence and Special Branch." [25]

Under cross examination at the Saville Inquiry INQ1873 also confirmed (albeit more equivocally) Mooney's engagement in psyops:

- Q. Did you form a working party with Hugh Mooney to consider PsyOps matters?

- A. He shared my office, yes.

- Q. And so you discussed PsyOps matters between you?

- A. We discussed Information Policy matters generally, yes.

- Q. Could that include PsyOps?

- A. Yes. [26]

Bloody Sunday

Mooney spent the day of Bloody Sunday manning phones at HQNI. Following the shootings, David Gilliland called from Stormont and urged him to get out an Army statement as soon as possible:

- By this time it was too late to get anything into the first editions of the London newspapers which would be read in Ireland. The best the Army could do was to put its side of events on the early morning radio bulletins. I decided to offer the local BBC correspondent, Chris Drake, an interview with Maurice Tugwell, who had spent the day in Londonderry with Major-General Robert Ford, Commander Land Forces. When Tugwell returned, I told him what I had done and he agreed it was in the Army's interest to do the interview. I remember him saying something like: "We had better see if Int have traces on any of these people."

- I then went home but came back to sit in on the interview with Drake. Tugwell then told me that four of the victims were "wanted" or "on the wanted list". By that I took him to mean that Int had some trace of involvement with the IRA. He said as much in the interview. Drake played the tape back to Tugwell and commented that he sounded a bit mild and conciliatory, and suggested that Tugwell might do it again in a harder tone of voice. This Tugwell did. The broadcast was a last-minute, improvised, damage-limitation exercise. It became necessary because no provision had been made for a coordinated public relations response at HQNI, simply because the Bloody Sunday killings had not been foreseen.[3]

Mooney also told the Bloody Sunday Inquiry that army officer INQ 1873 told him the following day of a conversation he had with Major General Ford the day after the shootings:

- "Make sure you get that on the front page", the general had said. [INQ 1873] told me he was kicking himself for not responding: "I guarantee it, General".[3]

In his statement to the inquiry Mooney made reference to a fallacious claim that on bloody Sunday IRA gunmen had impersonated British paratroopers using stolen uniforms and had themselves fired on the demonstrators in order to discredit the Army. Describing how the story appeared in the Daily Mirror under the byline of Chris Buckland on the 5th of April 1972, Mooney describes the story as "obviously the result of an army PR briefing..."[27]

Mooney claimed that the Army had received intelligence prior to the march indicating that the IRA planned to use the marchers as cover for their gunmen to fire on the Army.[28] Mooney stated that he encouraged Daily Telegraph journalist Thomas Edwin Utley to write a book, Lessons of Ulster (published in 1975), in response to the Widgery Tribunal. The book claims that the IRA used the civil rights march as a cover to fire on the Army as they entered the bogside: "IRA gunmen fired on the 'invading' force and the soldiers returned fire. The result was a gun battle fought in the midst of a milling crowd."[29]

Mooney further claims that the Army was not aware of any assurances from the IRA that they would not intervene in the civil rights march as claimed by Colin Wallace.[30] Utley's book was described by Mooney as part of a post-Widgery tribunal "propaganda offensive."[31]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry - Volume IX - Chapter 178 - Psyops and military information activity. Accessed 8 February 2013

- ↑ Report of the The Bloody Sunday Inquiry - Volume IX - Chapter 178, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 15 June 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Statement of Hugh Mooney, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, KM6. Accessed 10 February 2014.

- ↑ Hugh Mooney IN THE MATTER OF THE BLOODY SUNDAY INQUIRY HUGH MOONEY STATES By way of supplementary statement, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 11 September 2002, KM6.10. Accessed 19 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney IN THE MATTER OF THE BLOODY SUNDAY INQUIRY HUGH MOONEY STATES By way of supplementary statement, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 11 September 2002, KM6.11. Accessed 19 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney Statement of Hugh Mooney, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 22 January 2000, KM6.4, Accessed 8 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney IN THE MATTER OF THE BLOODY SUNDAY INQUIRY HUGH MOONEY STATES By way of supplementary statement, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 11 September 2002, KM6.24. Accessed 8 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney IN THE MATTER OF THE BLOODY SUNDAY INQUIRY HUGH MOONEY STATES By way of supplementary statement, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 11 September 2002, KM6.29. Accessed 8 February 2014

- ↑ INQ1873 INQ1873 under cross examination at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002 Pg. 012. Accessed 23 February 2014

- ↑ INQ1873 under cross examination at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002 Pg. 057. Accessed 23 February 2014

- ↑ INQ1873 under cross examination at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002 Pg. 61. Accessed 23 February 2014

- ↑ IN THE MATTER OF THE BLOODY SUNDAY INQUIRY HUGH MOONEY STATES By way of supplementary statement, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 11 September 2002, KM6.10. Accessed 19 February 2014

- ↑ Colin Wallace Colin Wallace under cross examination at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 18 September 2002 Pg. 154. Accessed 22 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney IN THE MATTER OF THE BLOODY SUNDAY INQUIRY HUGH MOONEY STATES By way of supplementary statement, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 11 September 2002, KM6.36.1. Accessed 8 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney IN THE MATTER OF THE BLOODY SUNDAY INQUIRY HUGH MOONEY STATES By way of supplementary statement, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 11 September 2002, KM6.14. Accessed 19 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney IN THE MATTER OF THE BLOODY SUNDAY INQUIRY HUGH MOONEY STATES By way of supplementary statement, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 11 September 2002, KM6.31. Accessed 19 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney Visit to Northern Ireland, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 3 November 1970 KM6.62. Accessed 8 February 2014

- ↑ Colin Wallace Colin Wallace under cross examination at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 18 September 2002 Pg. 153. Accessed 22 February 2014

- ↑ Colin Wallace Colin Wallace under cross examination at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 18 September 2002 Pg. 154. Accessed 22 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney Letter from Hugh Mooney to Mr. Welser, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 April 1971 Pg. 125. Accessed 24 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney Letter from Hugh Mooney to Mr. Welser, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 April 1971 KM6.119. Pg. 125. Accessed 24 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney Letter from Hugh Mooney to Mr. Welser, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 April 1971 KM6.118/KM6.119. Pg. 124/125. Accessed 24 February 2014

- ↑ New Ulster Movement N.U.M. Annual Report 1970-71, December 1971 Pg. 5. Accessed 24 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney Letter from Hugh Mooney to Mr. Welser, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 April 1971 KM6.120 Pg. 126. Accessed 24 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney Letter from Hugh Mooney to Mr. Welser, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 April 1971 KM6.120 Pg. 126. Accessed 24 February 2014

- ↑ INQ1873 INQ1873 under cross examination at the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2 October 2002 Pg. 012. Accessed 23 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney Satement of Hugh Mooney, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 22 January 2000 KM6.4. Accessed 8 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney IN THE MATTER OF THE BLOODY SUNDAY INQUIRY HUGH MOONEY STATES By way of supplementary statement, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 11 September 2002, KM6.41. Accessed 19 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney IN THE MATTER OF THE BLOODY SUNDAY INQUIRY HUGH MOONEY STATES By way of supplementary statement, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 11 September 2002, KM6.47. Accessed 9 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney IN THE MATTER OF THE BLOODY SUNDAY INQUIRY HUGH MOONEY STATES By way of supplementary statement, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 11 September 2002, KM6.48. Accessed 9 February 2014

- ↑ Hugh Mooney Letter from Hugh Mooney to JL Welser, Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 21 March 1972, KM6.54. Accessed 21 February 2014