Bob Lambert

This article is part of the Undercover Research Portal at Powerbase - investigating corporate and police spying on activists

Robert Lambert, commonly known as Bob Lambert and sometimes styled Dr Robert Lambert MBE, born February or March 1952,[2][3][4] , is a former Metropolitan Police officer turned academic.

A long-serving officer with the Metropolitan Police Special Branch, Lambert was a key member of its secretive Special Demonstration Squad. He served both as an undercover officer - using the false identity ‘Bob Robinson’ to infiltrate the environmental and animal rights protest movement in the 1980s - and then later as an influential manager of the unit in the 1990s.

He subsequently set up the Muslim Contact Unit within Special Branch, which worked with British Islamists purportedly to temper radicalisation, before retiring from the police in 2007. He then began a successful second career as an academic, building on his work at MCU.

In October 2011 he was publicly exposed as having been a police spy by some of the London Greenpeace activists upon whom he had spied.[5]

+++++ Last Updated February 2018 +++++

The profile of Bob Lambert presented here is the first of a collection, it will supplemented by additional pages covering specific areas of interest over time:

- Bob Lambert

- Bob Lambert as Bob Robinson

- Bob Lambert Exposure and Post-Exposure

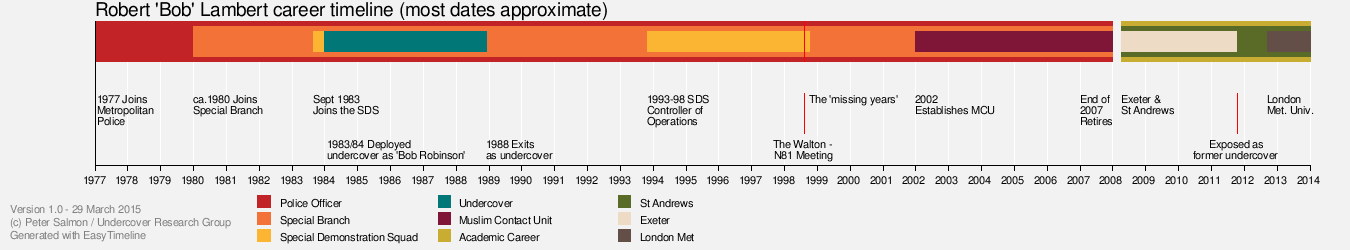

- Bob Lambert Career Timeline

- Bob Lambert and the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry

- Bob Lambert Consultancy

- Bob Lambert and the Academic Community

- Bob Lambert and the Muslim Community

- Bob Lambert Writing and Speaking

- Bob Lambert Gallery

Corrections or additions? Please contact the UndercoverResearch Group (and ask for our PGP key if you need it).

Contents

- 1 Biography of Bob Lambert

- 2 Overview of undercover tour as ‘Bob Robinson’

- 3 Subsequent career in policing

- 4 Summary of academic career

- 5 Lambert's own writings, speaking engagements and media appearances

- 6 Post-Met consultancy and other business interests

- 7 Exposure and post-exposure issues

- 8 Supporters and critics of Lambert

- 9 Court cases

- 10 Additional Undercover Research resources

- 11 Notes

Biography of Bob Lambert

Personal background of Bob Lambert

Bob Lambert was born in early 1952; documents lodged at Companies House indicate that he was born in March,[6] whilst a New Yorker article claims that his birthday is 12 February.[2]

Lambert's grandfather Ernest served in the Metropolitan Police for a quarter-century from 1899 until his retirement as an Inspector in 1924.[7][8] Ernest Lambert died in 1963.[9] Little is currently known about his parents or other antecedents, except that his father was “a London printer and a British soldier” who “entered the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp to help rescue Jewish survivors at the end of the Second World War,” and was subsequently “a staunch supporter of a post war reforming Labour government that set great store by social justice and support for the underprivileged.”[7]

During the 1980s, at the same time as pretending to be animal rights activist ‘Bob Robinson’, Lambert maintained a home in suburban Hertfordshire with his then-wife and their two children.[10][11] Their daughter died suddenly aged seventeen in 1992, their son Adam in February 2011.[2][12][13] Both are believed to have suffered from the same congenital heart disorder.[14][15]

After divorcing his first wife, Lambert was later remarried to Julia[16] (referred to in the New Yorker as ‘Katharine’[2]).

As well as the aforementioned Lambert family home in Hertfordshire in the 1980s, by the late 1990s Lambert is described as living in a house in north London.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag by Jacqui (previously pseudonymised as ‘Charlotte’[17]), an animal rights activist on whom he had spied.[18] Jacqui only discovered that the man she had known as ‘Bob Robinson’, who got her pregnant in 1984[19] but disappeared in 1988, had in fact been an undercover policeman when she saw a newspaper story with his photograph in it in June 2012.[20][21][2]

Legal action begun by Jacqui led to the Metropolitan Police formally acknowledging Lambert as a police infiltrator under the ‘Bob Robinson’ identity, and to it making a significant out-of-court settlement in relation to the behaviour of the service and its officer.[22][23]

He is a supporter of Chelsea Football Club, regularly attending matches with other police officers including his former SDS and MCU colleague Jim Boyling.[24] Lambert also shares with Boyling a passion for running, and both attend running club events on the outskirts of London.[2][25][26][27][28]

Summary of police career

- For a more detailed chronology of his work in the Met and in later years, see: Bob Lambert Career Timeline

Lambert is described as having joined the Metropolitan Police in 1977, aged 25, enjoying a thirty-one year long career before retiring in 2007[29][30][31] - though some discrepancies in his claimed biography have been noted.

Little is known about his earliest years in the Met, except for a passing reference by him to working a beat in the North London district of Camden.[32] He is reputed to have joined Metropolitan Police Special Branch (MPSB) in 1980, before being recruited to its secretive Special Demonstration Squad sometime between then and 1983. He was deployed undercover as ‘Bob Robinson’ from at least early 1984 until late 1988.[33]

Subsequently he worked in E Squad, a section devoted to non-Irish international terrorism,[34] until 1993. He returned to SDS as its Operational Controller, with the rank of Detective Inspector. He left SDS in 1998, and it is not clear what his role was until January 2002, when he set up the Muslim Contact Unit. He led the MCU from this time, through the 2006 merger of MPSB (also known as SO12) with the Metropolitan Police Anti-Terrorist Branch (ATB or SO13) which created Counter Terrorism Command (also known as SO15), until his retirement in December 2007.[35] Lambert has at times indicated that he was unhappy with the merger,[36] noting his divergence from the investigatory-minded direction in which the first CTC head, Peter Clarke, took it.[37]

In June 2008, Lambert was awarded the MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) “for Services to the Police”.[38]

After leaving the Met, Lambert built upon his MCU work and began a successful second career as an academic specialising in engagement with British Islamists, purportedly to temper radicalisation.[39][40][41][42][43]

Overview of undercover tour as ‘Bob Robinson’

- For a more detailed chronology of Lambert's undercover tour, see separate article: Bob Lambert as Bob Robinson

‘Bob Robinson’ first appeared in the animal rights and environmental milieu in north London late 1983 or early 1984.[2][29][44][1] His deployment followed that of the first known SDS officer sent to live amongst animal rights activists, Mike Chitty, who appeared in South London in early 1983.[45]

His infiltration into animal rights circles began with regular attendance at demonstrations, where he made the acquaintance of genuine activists, including Jacqui.[29][2] He soon became a familiar face at protests, and offered to drive people to and from events. He took part in hunt sabotage, protests against businesses associated with animal products, and joined London Greenpeace, an anarchist-leaning group involved in environmental and social issues.

Having established himself on the scene, he took on more responsibilities and a more active role in various campaigns and groups, and “set about befriending campaigners suspected of being in the ALF” [Animal Liberation Front].[46] He wrote or co-wrote a number of activist documents, including London Greenpeace's What's Wrong With McDonald's? factsheet - which was later subject to a notorious libel suit issued by McDonald's. Throughout his undercover tour as ‘Robinson’, Lambert implied to activists that he was interested in or already involved in more clandestine forms of political activity, such as that associated with the cells of the Animal Liberation Front (ALF).[47]

As an activist in an ALF cell,[48] he was implicated in the burning down of the Harrow branch of the Debenhams department store as part of a coordinated incendiary device operation which also saw branches in Luton and Romford targeted at the same time on the same night.[49][50][51][52][50] The 1987 attacks, which caused an estimated £340,000 worth of damage on the Harrow branch alone, with £4 million in fire damage and £4.5 million in trading losses across all three,[53][54] was credited with precipitating the ending of Debenhams' involvement in the fur trade.[55]

The other two members of ‘Robinson’'s cell, Geoff Sheppard and Andrew Clarke, were both arrested and subsequently imprisoned.[51][52][56][57][58] The 2015 “forensic external examination” of SDS-related documents undertaken by Stephen Taylor for the Home Office obliquely references Lambert's involvement in securing the arrests of Sheppard and Clarke, and indicates that the then-Home Secretary Douglas Hurd complimented the unit on its operation.[59]

Lambert remained deployed in the field as ‘Robinson’ until late 1988.[60][61] Using the pretext of being under investigation by police for his involvement in the 1987 Harrow Debenhams' arson - which included a Special Branch raid on the home of non-activist Belinda Harvey “to add credibility to Lambert's cover story”[62] - ‘Robinson’ told Harvey and other friends, including his son's mother Jacqui, that he needed to go ‘on the run’ to avoid capture; to some he said that he planned to move to Spain until things quietened down.[63] He then “abandoned his flat and stayed for a couple of weeks in what he called a ‘safe house’”,[62] before spending a farewell week with Belinda at a friend's house in Dorset in December 1988.[64] With this, he disappeared out of their lives, with a few postcards postmarked Spain and sent in January 1989 the only indication that he still existed.[64]

Subsequent career in policing

Whilst the precise details of Lambert's entire police career are not currently known, we do have an idea of what he did and when for much of his service in the Met; anyone who could help us, please do get in touch (and ask for our PGP key if you need it).

E Squad (1989-1993)

After being pulled out of his SDS undercover tour, Lambert was redeployed elsewhere in MPSB, first finding a new home in E Squad,[65] which dealt with worldwide terrorist threatsCite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag[66][67]

In his 2011 book (and elsewhere[68]), Lambert refers to how “in the 1980s Special Branch officers would meet Sikh community representatives in London to discuss the terrorist threat posed by Sikh extremists,”[69] a theme he returned to in a Chatham House lecture where he explicitly noted the involvement of E Squad (“a wonderful department”).[70] However, in neither version is it clear whether he himself was involved in this community engagement work with Sikhs.

It was whilst working in E Squad that Lambert appears to have first engaged with Muslim communities. In 1991 he was the officer who arrested Omar Bakri Mohammed[71][72] for making threats against Prime Minister John Major in relation to the Salman Rushdie affair. Bakri had issued a ‘fatwa’ against the PM and suggested him a target for assassination; for this Bakri was detained and questioned for two days by MPSB before being released without charge.[73]

Lambert's early engagement with Muslims centred around the London Central Mosque, where “prominent figures” such as Zaki Badawi and security manager Fasli Ali had success in “combating violent extremism and maintaining order in the face of serious challenges”. He notes that this made London Central Mosque “a role model and source of partnership support” on which he would later draw in his Muslim Contact Unit work, particularly at the Finsbury Park Mosque in the early 2000s.[74]

Lambert has claimed that he “helped colleagues from the FBI on the first World Trade Center attack” in 1993[75][76] and that he “was involved in the investigation”,[70][77] stating that he “was able to ask a Muslim community leader in London for help in clarifying the details of the time spent in the UK of one of the suspects.”[32] (Presumably this suspect was Ramzi Yousef (nephew of 9/11 architect[78] Khalid Sheikh Mohammed), who had lived and studied in the UK for four years before going first to Kuwait then on to train in Pakistan, before next heading to the US.[79][80][81])

Return to SDS (1993-1998)

In November 1993 Lambert returned to SDS, taking on the role of Controller of Operations.[82] This put him in the position of running the whole unit on a day-to-day basis,[83] working under its titular head, Detective Chief Inspector Keith Edmondson.[84][82][85][86] According to the Ellison Review, by August 1998 he had overall lead of the unit, having been made up to Acting Detective Chief Inspector.[87]Lambert states he left SDS sometime in 1998.[84]

Management decisions

In 1997 it seems that Lambert unilaterally broadened the mission of the unit, extended its reach beyond the Greater London area to the whole of the UK, and changed its name from ‘Special Demonstration Squad’ to ‘Special Duties Section’ in order to “reflect the increasing remit, and to meet customer requirements”. In his third Operation Herne report Chief Constable Mick Creedon registers surprise that this appears to have been executed without being directly sanctioned by Lambert's seniors, noting that it “demonstrates the considerable autonomy and influence that the Detective Inspector had within the management structure of the unit, and the apparent lack of Senior Management and Executive oversight.”[88]

Authorship of SDS documents

Lambert is believed to have contributed significantly[89][90] to the SDS Tradecraft Manual, which the first Herne Report describes as “an organic document of initiatives, operational learning, guidelines and suggestions from established UCOs to assist other UCOs [undercover officers] in their deployments”.[91] In addition, it is claimed that in 1997 Lambert penned a confidential Special Branch document called Withdrawal Strategy, which discussed Peter Francis' exfiltration from his undercover deployment.[92]

According to Evans and Lewis, at some point around June 1992 (when still in E Squad) Lambert was tasked by Special Branch superiors “to discreetly study the rogue officer” Mike Chitty,[74] who had been Lambert's contemporary as an SDS undercover officer infiltrating animal rights activists in the mid-1980s. The culmination of Lambert's eighteen month covert inquiry into Chitty was a “highly confidential” forty-five page report written in May 1994 (by which time he had returned to SDS as its Operational Controller), which was then “stored under lock and key in a Scotland Yard archive”.[93] (For more detail, see the profile on Mike Chitty)

The Ellison Review mentions additional pieces of SDS paperwork written by Lambert. These include a “briefing note” outlining the work of undercover officer N81 and how it touched upon the Stephen Lawrence family campaign;[94] and a “file note” dated 18 August 1998 which summarises the 14 August meeting hosted by him between Richard Walton and N81.[95]

The Stephen Lawrence murder investigation, Macpherson Inquiry and Ellison Review

- See main articles: N81, Bob Lambert and the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry, and N81: meeting with the Lawrence Review Team

In April 1993, black teenager Stephen Lawrence was murdered in a racially motivated attack by a gang of white youths whilst he waited for a bus in the south-east London neighbourhood of Eltham. The failure of the Metropolitan Police to promptly secure evidence, follow up on information received, protect witnesses or interview suspects led to a public outcry, and subsequently to the Macpherson Inquiry, which found the MPS investigation to have been stymied by incompetence, corruption and “institutional racism”.[96]

In August 1998, when the leadership of the Met under Commissioner Paul Condon was formulating its response to Macpherson Inquiry, Bob Lambert hosted a meeting at his own home in north London between undercover officer ‘N81’ and (Acting) Detective Inspector Richard Walton. At the time N81 was infiltrating a left-wing political group close to the Stephen Lawrence family justice campaign, whilst Walton was a member of the Met's ‘Lawrence Review Team’, and soon to join John Grieve's newly established Racial and Violent Crime Task Force, or CO24.[97].

The existence of this clandestine meeting were not publicly known until March 2014, when Mark Ellison QC revealed details about it in The Stephen Lawrence Independent Review, with a less in-depth account in the simultaneously released third Herne report.[98][99][100][101][102]

1998-2001 - the ‘missing years’

It is not clear what Lambert did between leaving SDS sometime after August 1998 and the establishment of the Muslim Contact Unit in January 2002.

Biographies - in writings he authored - indicate that he remained with Metropolitan Police Special Branch throughout that time.[103] No evidence has so far come up to suggest he was involved in, for example, Territorial Policing, that he was transferred to other Branch-level units such as the Anti-Terrorist Branch, or that he transferred to a police force other than the Metropolitan Police Service.

By implication, Lambert seems likely to have been working in a different unit or units within MPSB during this time period. One biography notes that from beginning in MPSB in 1980 until 2006 or 2007, Lambert had dealt “with all forms of violent political threats to the UK, from Irish republican to the many strands of International terrorism.”[104] Whilst his work on international terrorism at E Squad has already been noted, an involvement in Irish republican matters would suggest time served in B Squad (though it is by no means clear whether that would have occurred at this point of his career or in Lambert's pre-SDS years).

Muslim Contact Unit

- See forthcoming article Muslim Contact Unit for more detail.

In January 2002 Lambert set up the Muslim Contact Unit (MCU) within Special Branch, “with the purpose of establishing partnerships with Muslim community leaders both equipped and located to help tackle the spread of al-Qaida propaganda in London.”[105][30][106][107]

The avowed strategy of the MCU under Lambert was to “set about identifying the Muslims they believed were best equipped to take on the so-called “hate preachers”, chief among them the infamous Egyptian Abu Hamza, who were believed to be serving as propagandists for al-Qaeda in London”, most notably at Brixton and Finsbury Park.[108] Typically this approach meant working with Muslims characterised as ‘Islamists’ or ‘salafis’ - a path which Lambert himself notes was directly in conflict with prevailing counter-terrorism policing opinion on dealing with political Islam which cautioned “against accommodating ‘traditionalists’” and “lump[ed] salafis and Islamists together as ‘radical fundamentalists’”.[109][110]

Reflecting on his time at MCU, Lambert has latterly claimed that the unit “was a graveyard in career terms,” and that he realised he would never rise above Detective Inspector.[75]

Summary of academic career

- See forthcoming page Bob Lambert - academic career for a more detailed account

According to Lambert his involvement in academic issues began in 1995, when he received a First from the Open University for an interdisciplinary undergraduate degree on European cultural history.[111] In 2003 - whilst running MCU - he received a First from Birkbeck College at the University of London for his Masters.[112]

Following his retirement from the Met, in 2008 he took up a place as a PhD student at the University of Exeter, an institution with which he maintained links until at least 2011 (in October of which he was exposed as a spy).[7] From 2008 he also began teaching on a course managed by St. Andrews University.[111][113] In 2012 he took up a senior lecturing position at London Metropolitan University.[114][115][116][117]

In 2010 he was awarded his doctorate by University of Exeter for his PhD dissertation The London Partnerships: an Insider’s Analysis of Legitimacy and Effectiveness.[118][119][112] This dissertation (and the research underpinning it) later became the basis of his book, Countering Al-Qaeda in London: Police and Muslims in Partnership,[120] as well as numerous other pieces of work.[121][80][81][122]

Despite his retirement from the police in 2007, Lambert continued to engage with the Muslim Contact Unit through his academic work.[123]

Just before Christmas 2015, Lambert quit his jobs at both his academic posts, after campaigners had written to St Andrews' principal Louise Richardson.[124]

University of Exeter & EMRC

After retiring from the Met in late 2007, he became a Research Fellow at the Institute for Arab and Islamic Studies in the University of Exeter's politics department, a post he held from 2008 until 2011.[125][126]

Whilst at Exeter there he became closely associated with Professor Jonathan Githens-Mazer, and in September 2009 the two together set up the European Muslim Research Centre (EMRC),[118] which was officially launched the following January.[127][128]

Following the public exposure of Lambert as a former undercover police officer in October 2011, Exeter's university management has remained tight-lipped, making no statement about its errant academic, despite having previously heralded much of his work - right up to September, when the press office plugged the launch of Lambert's book at the Houses of Parliament.[129]

Since then, though, the EMRC appears to have been quietly dismantled, with Lambert and erstwhile collaborator Jonathan Githens-Mazer parting ways, and the Centre's website allowed to rot away, his name as co-director of the Centre being removed from the website sometime between June and August 2012.[130][131] According to journalist Rob Evans in 2015, Exeter's management eventually confirmed to The Guardian that Lambert resigned from the university in October 2011 - the same month his undercover past was exposed - but beyond that “refused to explain”.[132]

St. Andrews University & CSTPV

In parallel to his post at Exeter, in September 2008 Lambert began teaching, lecturing and supervising dissertations on the e-learning MLitt terrorism studies course provided by St. Andrews University's Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence (CSTPV), a key academic location on the the international terrorism studies circuit.[30][125][133]

Since at least 2006 former senior Metropolitan Police officer David Veness - who as Assistant Commissioner (Specialist Operations) had direct oversight of SDS between 1994 and 2005, as well as a personal working relationship with Lambert through the offices of the Muslim Safety Forum, which Veness chaired - has held the position of Honorary Professor of Terrorism Studies at CSTPV.[134]

London Metropolitan University & John Grieve Centre

In September 2012 - that is, nearly one year after his exposure as a police spy - Lambert was hired by the John Grieve Centre for Policing and Community Safety (also known as JGC), an under- and post-graduate criminology unit based at the London Metropolitan University.[135][136]

Lambert's role at London Met was not merely as a teacher, but as a course leader on the undergraduate Criminology and Law course,[115][116] and as part of the team running the university's Professional Doctorate in Policing and Security (“the only doctorate course specifically in policing in the country”). For his work on the latter Lambert was fulsomely praised by vice-chancellor Malcolm Gillies in July 2013 “for giving excellent supervision while ensuring the course goes from strength to strength.”[137] It is not known whether Lambert has continued his involvement on the undergraduate course.[138]

The John Grieve Centre was originally established and led by former MPS senior officer (and recurring figure in the story of undercover policing) John Grieve at Buckinghamshire Chilterns University College in 2003, before it was transferred to London Metropolitan in April 2006.[135][136]

Of the seven ‘John Grieve Centre Team’ members noted by London Met's website other than Lambert himself, three have Metropolitan Police backgrounds, two worked for either MPS Anti-Terrorist Branch (SO12) or Special Branch (SO13) (now combined together as Counter Terrorism Command or SO15), two are alumni of St. Andrews University's Terrorism Studies course, and one has close connections to the University of Exeter's EMRC.[139]

Resignation

In December 2015, after a long-running picketing campaign in London and a series of articles about undercover officers operating in Scotland, Bob Lambert announced his resignation from both his academic posts. According to a University of St. Andrews spokesman, Lambert tendered his resignation with effect from the end of the current term.[140][141][142][143][144]

The announcement came a week after a letter to university principal Louise Richardson at St. Andrews, signed by spied-on activists Helen Steel, Lois Austen and Dave Smith, as well as journalist-activist George Monbiot (who had been awarded an honorary doctorate from St. Andrews):

- We believe that his [Lambert] past conduct as a central figure in the Metropolitan Police’s Special Demonstration Squad means that he is supremely unsuitable for teaching and shaping the thoughts of others in his current position.

- The SDS’ abuse of citizens and undermining of legitimate campaigns are one of the darkest corners of Metropolitan Police history. Lambert is no role model and should not be trading on his abuses.

The letter gave a detailed account of Lambert’s history as an SDS officer and further noted:

- One has to wonder, if all this is not enough to make him unfit to teach others, what does it take? With fresh revelations coming to light almost weekly and the public inquiry about to begin, we can be confident there will be more.[124]

Lambert's own writings, speaking engagements and media appearances

- See forthcoming page Bob Lambert Writing and Speaking for the fullest compendium yet of such material

From his retirement at the end of 2007 until his exposure in late 2011, Lambert built up a reputation as an expert on islamophobia and police-Muslim community engagement. This enabled him to speak at many academic and political events, to have articles accepted by peer-reviewed journals, to be interviewed by both specialist and mainstream media, and even gave him regular opinion pieces in the ‘Comment is Free’ section of The Guardian website.[145]

Subsequent to his unmasking as an SDS spy in October 2011, his appearances on conference platforms, in learned journals and as an invited author in the pages of liberal newspapers have been noticeably reduced.[146]

Post-Met consultancy and other business interests

- See also the forthcoming in-depth page Bob Lambert consultancy

Following his retirement from the police, Lambert became a director of a number of companies, each of which was directly connected to his academic work and contacts, but which were also linked to his past work in Special Branch.[147]

STREET UK

In the words of founder Dr Abdul Haqq Baker, the Lambeth-based islamic youth outreach project ‘Strategy To Reach Empower and Educate Teenagers’ (also known as ‘STREET UK’) was set up “to provide alternative and safe environments for young Muslims to interact and comfortably express themselves among peers sharing ideas, aspirations and concerns.”[148] It should be noted that STREET, whilst not officially incorporated until 2008, had been mooted as a project at least as early as 2006,[149][150] and by Baker's account was active from March 2007[151][152] (though some other sources put STREET's foundation as taking place in 2006).[153]

STREET was set up as a company by two Hertfordshire-based business registration services, Qa Nominees Ltd and Qa Registrars Ltd.[154]. Its business address - both in terms of a registered and a trading address - was given as 54 Anson Road in Cricklewood, north-west London.

Bob Lambert was appointed director[155] with Dr Abdul Haqq Baker, the initiator of STREET.[156][157]

Lambert started this company after his retirement from the Met, but before he took up his posts at either St. Andrews University or the University of Exeter.[158]) A salafi convert from Brixton, Baker worked with Lambert at least as far back as 2002, when MCU made contact with leading members of Brixton Mosque in the wake of the arrest of attempted ‘shoe-bomber’ Richard Reid[159], and they subsequently became academic colleagues. This academic partnership began at St. Andrews University, where - like Lambert - Baker lectured on the CSTPV Terrorism Studies course; and continued at the University of Exeter, where Baker was a research fellow in the EMRC run by Lambert.[160][161]

Lambert's own son by his first wife, Adam, was seemingly also involved in STREET. According to Lambert he “played a pivotal role in establishing [STREET] as an effective and legitimate youth outreach project in Brixton”, working as its operations manager from July 2008 until his death in February 2011.[12]

Lambert Consultancy and Training Ltd

In August 2008 Lambert set up a company called ‘Lambert Consultancy and Training Limited’, with his second wife Julia as its secretary, and - as with STREET - its registered address was given as 54 Anson Road in Cricklewood, north-west London. In March 2009 Lambert brought in his academic collaborator from the University of Exeter, Dr Jonathan Githens-Mazer, and Githens-Mazer's wife Gayle, as directors of the company. The company was dissolved one year later on 30 March 2010, having filed no accounts.[162][163]

Siraat Ltd

In January 2009 Lambert, along with Raymond Boakye and Carey Anderson, set up Siraat Ltd, a “prison-based mentoring project across southern England”[164] with an address at a business centre on Coldharbour Lane in south London's Brixton.[165]

Siraat filed its last accounts in January 2010, its last tax return in January 2011, and was officially dissolved in July 2014. Neither Lambert - who as designated company secretary had legal responsibilities for ensuring timely business filings to Companies House - nor the others formally resigned as directors before Siraat's dissolution.[166]

In addition to his directorship of Siraat Ltd, Carey Anderson - under the name Abdur Rahman Anderson - was also a director of Street Consultancy Ltd, which he set up with Abdul Haqq Baker (who used the name Anthony Baker) in March 2007, with a third director and trustee, Sameer Koomson, joining in June 2007. Like STREET and Lambert's own consultancy, this too was registered to the 54 Anson Road address in Cricklewood.[167]

West London IMPACT

Whilst Lambert was never directly involved as a company director, he was tangentially connected to the Initiative for Muslim Progression And Community Tolerance (West London IMPACT) project. IMPACT was set up in December 2009 by Abdul Haqq Baker, Valerie Chung and Najeeb Ahmed, using company formation agent Graham Cowan and with a trading address in the West London neighbourhood of Southall. Baker and Chung both resigned as directors in March 2012, leaving Ahmed in charge. The organisation remained extant and up to date with its business filings as up until its dissolution in February 2013.[168]

Withdrawal of government funding

STREET, Siraat and IMPACT initially all received significant income (estimated by the Daily Telegraph to be nearly £1.3 million) through the counter-terrorism funding stream administered by the Office for Security and Counter-Terrorism (OSCT).[164]

By February 2011 all three had their government grants cut by OSCT as part of a shake-up of the government's ‘Preventing Violent Extremism’ - or PREVENT - strategy.[169]

Exposure and post-exposure issues

- For a more detailed account, look out for the forthcoming page Bob Lambert Exposure and Post-exposure

Having worked undercover as ‘Bob Robinson’ from early 1984 until late 1988 without being exposed, Lambert came out of the shadows somewhat in the mid-2000s in his new role as head of the Muslim Contact Unit. Whilst as a Special Branch officer he was not a wholly public figure, his community engagement work did see him make some public statements at least as far back as 2006.[170][171][172][173][174] At the same time as his police career was winding down, his academic work began to take off. By November 2007, he had been publicly lauded in person by both the Muslim Council of Britain[32][111][175][176] and the Islamic Human Rights Commission.[177]

Having retired from the Met, he seemed to fully embrace the public acknowledgement of his work (both positive and negative), and accepted invitations to speak at academic and political events as an expert on subjects such as community engagement policing or islamophobia. Whilst Lambert's past as an officer with the Metropolitan Police, and specifically with the MPSB, was to some degree known as he built up his academic reputation, Lambert did not publicise his own close involvement in its undercover operations. Indeed, in his book, discussing the work of fellow Special Branch officer-turned-academic and private sector consultant Lindsay Clutterbuck in analysing MPSB files from the 1880s, he noted disapprovingly that from its inception the Branch had favoured covert spying tactics over transparent interaction with particular communities: “Infiltration rather than community partnerships were the popular hallmarks of an elite police department first established in 1883 to combat the threat to the capital posed by Irish republican bombers.”[178]

It was after seeing videos of Dr Robert Lambert speak at anti-racism events that several former London Greenpeace campaigners determined that the ex-Special Branch officer-turned-academic was the same person as the animal rights activist they had known as ‘Bob Robinson’ in the 1980s. A group of them then decided to attend a Unite Against Fascism/One Society Many Cultures anti-racism conference at Congress House in Central London where Lambert was scheduled to speak on 15 October 2011, and publicly exposed him as a police spy.[179][180][181]

‘Apologies’ by Bob Lambert

Since his exposure in October 2011 as a former undercover police spy, Bob Lambert has made only a handful of public statements in relation to his time in SDS. Each of these can be seen to include only the barest admissions necessary at that time, with his words chosen extremely carefully.

We list and summarise each of them below:

- Lambert's reply to Spinwatch open letter (23 October 2011)

Following his public exposure, Spinwatch - which noted that it had “shared platforms with Bob Lambert...at public meetings and at academic conferences”[182] - published an open letter to Lambert calling on him to confirm or deny “the specific allegations so far made public...give an account of what you now think of your previous activities...disavow any previous activities [and] publically apologise to the activists who you allegedly betrayed.[183]

Lambert's response was to “apologise unreservedly for the deception I therefore practiced on law abiding members of London Greenpeace [and] for forming false friendships with law abiding citizens and in particular forming a long term relationship with [Name of person removed] who had every reason to think I was a committed animal rights activist and a genuine London Greenpeace campaigner.” However, he justified his actions by saying that he had been “deployed as an undercover Met special branch officer to identify and prosecute members of Animal Liberation Front who were then engaged in incendiary device and explosive device campaigns against targets in the vivisection, meat and fur trades,” and needed “the necessary credibility to become involved in serious crime”. He makes no specific mention of the Debenhams case, nor of the extended infiltration targeting London Greenpeace members by subsequent SDS officers such as John Dines or Jim Boyling, which he was at least in part responsible for supervising.[184]

- Response to The Guardian (23 October 2011)

The same day as Lambert's reply to Spinwatch was published, The Guardian also published a story based on “a statement” from Lambert “after the Guardian contacted him”. All direct quotations attributed to Lambert appear to be identical to sections of the Spinwatch reply, which is also referenced, which may imply that Lambert did not respond separately or differently to The Guardian.[185]

- ‘Rebuilding Trust and Credibility’ (1 February 2012)

Styled by Lambert as his own “preliminary commentary” on his role as a full-time police mole within London Greenpeace and other groups, ‘Rebuilding Trust and Credibility’ was a brief text which he placed on his profile page on the St. Andrews University website. In it he again plugged his book, points to his earlier public apology, and adds that he hopes to continue in his work with Muslim communities. He makes reference to “The recent trial of two members of a gang that murdered Stephen Lawrence in 1993” which “serves to remind us of the self inflicted damage the Metropolitan Police has had to overcome when seeking to rebuild trust with minority ethnic Londoners” - but of course says nothing about his own key role in facilitating the flow of secret intelligence from spies in the Lawrence family camp to the team leading the Met's whitewashed response to the Macpherson Report. He alludes to his relationship with Belinda Harvey, but due to the civil litigation by then begun, he rows back to “alleged”.[186]

- Interview with Channel 4 News (2-5 July 2013)

By the time of his first onscreen television interview since his exposure, the mother of the child whom Lambert fathered whilst undercover - Jacqui - had come forward, so now he admitted to having had four relationships with women whilst deployed in the field. Besides Jacqui and Belinda Harvey, nothing is publicly known about the other two. Lambert apologises to Jacqui and Belinda, but insists that he fell in love with them both. He refuses to say whether senior officers knew that he had fathered a child whilst undercover, but indicates that he will offer a full account to “the investigation team”, by which he presumably means Operation Herne. He denies that he was involved “in the planting or the ignition” of the Debenhams incendiary device. He admits that “on occasions” he was arrested as ‘Bob Robinson’ and implies that he used that identity more than once in court. He admits to co-authoring the McLibel leaflet, but denies knowing if McDonald's were aware of police involvement in the document. He again claims that his behaviour should not reflect negatively on his SDS colleagues, “the overwhelming majority” of whom “behaved impeccably at all times”.[187][44][188][189]

- Article in Critical Studies on Terrorism (7 April 2014)

Whilst rather illuminating in the way that he discusses - if somewhat opaquely - his work in SDS, early on in the article Lambert explains that he “will not write my own full account in response to [the Evans/Lewis book] Undercover and [Paul Lewis' television documentary] Dispatches until I have first discharged my legal obligations to the investigations and court proceedings”. Accordingly, there are no further specific apologies to allegations, only that he “accept[s] blame for mistakes I made as an undercover police officer in the 1980s” and that he has “made public apologies for them”. He states that he does “not accept the pejorative account of my role in undercover policing” by Evans and Lewis.[122]

Supporters and critics of Lambert

- See forthcoming page Bob Lambert - support and criticism for detailed examination of topic

Since his exit from the Metropolitan Police, Lambert has received both positive and negative acknowledgement of his work. Around the time of his retirement, he was presented with first a ‘Friends of Islam’ award by the Muslim Council of Britain,[32][111][175][176] and then a trophy from the Islamic Human Rights Commission “In appreciation for his integrity and commitment to promoting a fair, just and secure society for all, which, is a rarity and will be greatly missed”.[177] He was also inducted as a Member of the Order of the British Empire “for Services to the Police” in June 2008, enabling him to style himself ‘Dr. Robert Lambert MBE’.[190] A ‘Dialogue and Building Bridges’ award followed the next month courtesy of the Cordoba Foundation, at that year's Islam Expo.[120][111]

However, following his exposure by London Greenpeace activists in October 2011, Lambert has been targeted by a number of protests. On 9 February 2012 animal rights activists disrupted a public seminar at St. Andrews University which Lambert was scheduled to speak at,[191] reportedly leaving him “startled” as he was heckled over his activities as an undercover police spy. Leaflets detailing his infiltration were also distributed.[192]

Then in February 2013 two online petitions were started, one calling for Lambert to apologise and face disciplinary action from his then-employer St. Andrews University, the other demanding that he be stripped of his MBE.[193][194] To date, neither has drawn significant support.

Next, in October 2013 a preview of a documentary film on the subject of police infiltration of political activist groups was shown at St. Andrews University, and students leafleted to inform them of Lambert's past.[195] This followed a number of articles published in student magazine The Saint which outlined Lambert's role as a police spy.[196][197][198]

By March 2014 the London Metropolitan University branch of Unison had voted to support Campaign Opposing Police Surveillance, which works to publicise and resist police infiltration of political movements.[199] This was then followed by a “packed public meeting” on the subject hosted by Unison at London Met in November.[200][201] Later that year saw the creation of a group called [Islington Against Police Spies].[31] Comprising residents from the area around the university as well as those who studying or working in it, IAPS called for a series of pickets at London Met, describing Lambert as “a known liar, spy and exploiter of women - not in any way a fit person to be trusted teaching students at this University”, and with the aim of keeping up “pressure on London Met until they fire him”.[202][203][204][205][206][207] This then led to wider coverage of the issue in the national media.[208][132][209][210] London Met's management was then forced to defend Lambert publicly,[211] whilst a handful of individuals - notably the aforementioned fellow John Grieve Centre senior lecturer Tim Parsons, academic colleague Stefano Bonino[212][213] and Finsbury Park Mosque's Mohammed Kosbar[214][120] - have offered Lambert their public support.

Court cases

In December 2011 Lambert was named in legal proceedings brought by eight women - one of whom was Belinda Harvey - who had had long-term relationships with undercover officers.[215][216] The Metropolitan Police faced separate litigation from Jacqui, the unwitting mother of Lambert's ‘undercover son’. The Met settled this second suit out-of-court in October 2014 for £425,000.[217]

Additional Undercover Research resources

- N81

- N81: Profile from the Ellison Report,

- N81: Meeting with the Lawrence Review Team

- N81: File Notes SDS

- N81: IPCC investigation

- Lawrence Review Team

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Evans/Lewis book states that Lambert first met ‘Charlotte’, AKA Jacqui, in 1983, “the first year of his deployment”. This is slightly contradicted by the account in The New Yorker piece, which is based upon interviews with Jacqui, in which it is said the two met “in early 1984”. In his 2013 interview with Andy Davies for Channel 4 News, Lambert himself implies that it could not have been 1983, with the words “I must say, in 1984 when I adopted that identity [Bob Robinson]…” In a 2014 article for an academic journal, Lambert himself strongly implies that his undercover tour began in June 1984 and ended in December 1988 (see Robert Lambert, ‘Researching counterterrorism: a personal perspective from a former undercover police officer’. Critical Studies on Terrorism Volume 7 Number 1, pp165-181 (2014)).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Lauren Collins, ‘The Spy Who Loved Me: An undercover surveillance operation that went too far’, The New Yorker, August 25 2014 issue (accessed 30 September 2014).

- ↑ ‘ROBERT LAMBERT’, Companies House website, 2016 (accessed 25 May 2016).

- ↑ It should be noted that in all his Companies House registrations, Lambert's birth month is given as March 1952, whereas in her New Yorker article Lauren Collins states very specifically that “Bob’s real birthday is sixteen days earlier” than that of the original Mark Robert Charles Robinson, whose identity Lambert stole, which would put it at 12 February 1952. It is possibly that Collins meant sixteen days later, in which case it would be 16 March 1952.

- ↑ London Greenpeace, ‘Undercover police agent publicly outed at conference’, IndyMedia UK, 40831 (accessed 8 November 2014).

- ↑ Companies House, ‘Mr Robert Lambert’ (company director profile), DueDil.com (accessed 15 March 2014),

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Robert Lambert, Staff, Exeter University website (via archive.org), 2012 (accessed 19 April 2014).

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda In London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, C Hurst & Co, 2011, p3.

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda In London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, C Hurst & Co, 2011, p5.

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber/Guardian Books, 2013, p29. Note that a typo renders this as “suburban Herefordshire” - a county in the English West Midlands which lies 130 miles away from London - rather than Hertfordshire, which is immediately north of Greater London. Rob Evans has confirmed to the author that this was a simple proofreading mistake, and that Lambert's home during his SDS deployment (and subsequently) was in Hertfordshire not Herefordshire (correspondence, March-April 2015.)

- ↑ Frances Hardy, ‘Caught in a monstrous web of lies: They met. Fell in love. Had a baby. Jacqui thought she'd found the perfect man, in fact he was an undercover police officer’, Daily Mail, 3 December 2014 (accessed 4 December 2014).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda In London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, C Hurst & Co, 2011, p vii. Note that this dedication indicates that Lambert had inducted his acknowledged son into his Special Branch-related work at STREET UK.

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda In London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, C Hurst & Co, 2011, p13.

- ↑ Mark Duell, ‘Metropolitan Police agrees to pay £425,000 compensation to woman who had child by undercover officer: She had 'psychiatric care after learning of his real identity'’, Mail Online, 24 October 2014 (accessed 8 November 2014).

- ↑ Glenda Cooper, ‘Bob Lambert, undercover cops, and the awful cost of sleeping with the enemy’, Daily Telegraph, 25 October 2014 (accessed 8 November 2014).

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda In London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, C Hurst & Co, 2011, p.xi.

- ↑ See page on pseudonyms for more on the various names used as different times to refer to individuals targeted by police infiltrators.

- ↑ Rob Evans, Paul Lewis, ‘Undercover police had children with activists’, Guardian, 40928 (accessed 8 November 2014).

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber/Guardian Books, 2013, p47, (accessed 8 November 2014)

- ↑ Rob Evans, Paul Lewis, ‘Anatomy of a betrayal: the undercover officer accused of deceiving two women, fathering a child, then vanishing’, Guardian, 41326 (accessed 8 November 2014).

- ↑ Suzannah Hills, ‘Mother claims missing father of her child was undercover policeman accused by MP of leaving bomb in department store’, Mail Online, 6 February 2013 (accessed 8 November 2014).

- ↑ unknown author, ‘Met pays more than £400,000 to mother of undercover policeman and former Exeter University academic's child’, Exeter Express & Echo, 24 October 2014 (accessed 8 November 2014).

- ↑ Rob Evans, ‘Met police to pay more than £400,00 to victim of undercover officer’, The Guardian, 23 October 2014 (accessed 8 November 2014).

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber/Guardian Books, 2013, p160.

- ↑ Sue, ‘Jim Sutton – undercover cop in Reclaim the Streets’, Indymedia UK, 19 January 2011 (accessed 4 June 2014).

- ↑ Epsom Oddballs Running Club, ‘MABAC rep & Events Secretary’, Epsom Oddballs Running Club website (accessed 4 June 2014).

- ↑ nonsuchoffice, ‘A big thank you to today's volunteers for putting on another great event’, Nonsuch Parkrun website, 6 December 2012 (accessed 18 February 2015).

- ↑ Possible photograph of Bob Lambert (back row far left, 177) and Jim Boyling (back row fifth from left, 176) in: Lauren Nelson, Epsom Oddballs team photo, Epsom Oddballs Facebook page, 11 July 2011 (accessed 18 February 2015).

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013, p27.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Handa Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence staff page, ‘Dr Robert Lambert - Lecturer in Terrorism Studies’, University of St. Andrews website (accessed 15 March 2014).

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Tom Foot, ‘Holloway Road uni defends crime lecturer former cop who had undercover affair’, Islington Tribune, 31 October 2014 (accessed 8 November 2014).

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 Richard Jackson, ‘Counter-terrorism and communities: an interview with Robert Lambert’, Critical Studies on Terrorism volume 1 number 2, August 2008 (accessed 16 June 2014), p295.

- ↑ See later sections on ‘Bob Robinson’ for more details.

- ↑ Metropolitan Police Special Branch, Special Branch Introduction and summary of responsibilities, MPSB, August 2004 (released via Freedom of Information Act), p5.

- ↑ See section on Lambert's subsequent career for more details.

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda in London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, Hurst & Company, 2011, p60.

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda in London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, Hurst & Company, 2011, pp11 & 138.

- ↑ The London Gazette, ‘Supplement No. 1’, The London Gazette, 14 June 2008 (accessed 16 March 2014).

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda in London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, Hurst & Company, 2011, p230.

- ↑ Robert Lambert, ‘Salafi and Islamist Londoners: Stigmatised Minority Faith Communities Countering al-Qaida’, Arches Quarterly, Summer 2008 (accessed 22 November 2014).

- ↑ Nasar Meer, ‘Complicating ‘Radicalism’ - Counter-Terrorism and Muslim identity in Britain’, Arches Quarterly, Spring 2012 (accessed 22 November 2014).

- ↑ Robert Lambert, ‘Empowering Salafis and Islamists Against Al-Qaeda: A London Counter-terrorism Case Study’. Political Science and Politics, Volume 41 Issue 1, pp. 31-35 (2008).

- ↑ Tim Parry Johnathan Ball Foundation for Peace, Rethinking Radicalisation,Conference report, 12 October 2011 (accessed 18 November 2014).

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Andy Davies, ‘I'm sorry, says ex-undercover police boss’, Channel 4 News, Channel 4, 5 July 2013 (accessed 15 April 2014).

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013, pp 76-77.

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013, p34.

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013, p28.

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013, p36.

- ↑ BBC News, ‘Undercover policeman 'fire-bombed shop,' MPs told’, BBC News, 13 June 2012 (accessed 3 February 2015).

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Rob Evans, Paul Lewis, Richard Sprenger, Guy Grandjean & Mustafa Khalili, ‘Claims that police spy 'crossed the line' during animal rights firebombing campaign’, The Guardian, 13 June 2012 (accessed 3 February 2015).

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, ‘Call for police links to animals rights firebombing to be investigated’, The Guardian, 13 June 2012 (accessed 3 February 2015).

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Paul Lewis & Rob Evans, ‘Questions remain over animal rights activists' case’, The Guardian, 13 June 2012 (accessed 3 February 2015).

- ↑ unknown author, ‘Animal Front trial told of raid finding firebombs being made’, Glasgow Herald, 14 June 1988 (accessed via Google News archive, 3 February 2015).

- ↑ BBC News, ‘Green MP Caroline Lucas names undercover officer as shop fire bomber’, BBC News, 13 June 2012 (accessed 3 February 2015).

- ↑ Kevin Toolis, ‘In for the kill: Is human life of greater importance and worth than animal life?’, The Guardian, 5 December 1998 (accessed 29 August 2014).

- ↑ Rob Evans, ‘Home Office silence over Bob Lambert claim’, The Guardian, 29 June 2012 (accessed 3 February 2015).

- ↑ Kirsty Walker & Chris Greenwood, ‘Undercover policeman planted bomb in 1987 Debenhams blast that caused millions of pounds worth of damage to 'prove worth' to animal rights group he was infiltrating, claims Green Party MP’, Daily Mail, 13 June 2012 (accessed 3 February 2015).

- ↑ Suzannah Hills, ‘Mother claims missing father of her child was undercover policeman accused by MP of leaving bomb in department store’, Mail Online, 6 February 2013 (accessed 3 February 2015).

- ↑ Home Office, Investigation into links between Special Demonstration Squad and Home Office, Home Office, 12 March 2015(accessed 22 March 2015), pp3 & 19.

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber/Guardian Books, 2013, p54.

- ↑ The New Yorker article appears to suggest that Lambert was preparing to exfiltrate himself from as early as Autumn 1987: “[One morning] in the fall of 1987... [Bob] said that he had to leave because of the investigation into the Debenhams bombing. He was going abroad, and, for a while, it might be difficult to communicate. As soon as it was safe, he said, he would write. Jacqui could bring their son to visit him in Spain.” Lauren Collins, ‘The Spy Who Loved Me: An undercover surveillance operation that went too far’, The New Yorker, August 25 2014 issue (accessed 30 September 2014).

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013, p53.

- ↑ Paul Peachey, ‘Deceived lovers speak of mental 'torture' from undercover detectives’, The Independent, 1 March 2013 (accessed 8 November 2014).

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013, p54.

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013, p55.

- ↑ Paula Gilford, LinkedIn profile of Paula Gilford, LinkedIn.com website, 2014 (accessed 25 November 2014).

- ↑ Nigel West, Historical Dictionary of British Intelligence, Scarecrow Press, 2005, p586.

- ↑ Richard Jackson, ‘Counter-terrorism and communities: an interview with Robert Lambert’, Critical Studies on Terrorism volume 1 number 2, August 2008 (accessed 16 June 2014), p298.

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda in London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, Hurst & Company, 2011, pp241-242; he references this from ‘participant observation’ of a number of Special Branch officers and an interview with a further officer.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Dr Bob Lambert & Professor Rosemary Hollis, Partnering with the Muslim Community as an Effective Counter-Terrorist Strategy, Chatham House, 20 September 2011 (accessed 17 April 2014).

- ↑ Bakri is a Syrian-born Islamist who was long involved in activity in the UK from 1986 until his departure - consolidated by a government banning order preventing his return - in 2005. He led the British branch of Hizb ut-Tahrir and later founded al-Muhajiroun with Anjem Choudary.

- ↑ We have used the same spelling of Bakri's name used by Lambert (and others, e.g. Jon Ronson, THEM: Adventures with Extremists, Picador, 2001 and Mark Curtis, Secret Affairs: Britain's Secret Collusion with Radical Islam, Serpent's Tail, 2010), though it should be noted that Wikipedia and some other sources render it ‘Omar Bakri Muhammad’.

- ↑ Mark Curtis, Secret Affairs: Britain's Secret Collusion with Radical Islam, Serpent's Tail, 2012 (updated edition), p273.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013, p81.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Anonymous author, Notes on Bob Lambert at ‘9/11 Ten Years On’ conference, University of Strathclyde, 8-11 September 2011, September 2011, private document, September 2011.

- ↑ Anonymous author, Notes on Bob Lambert at Chatham House 20 September 2011, private document, September 2011.

- ↑ It is possibly of note that “By 2000, the FBI reassigned one of the Joint Terrorism Task Forces to investigate ELF arsons in Long Island, New York. The task force had previously investigated the...first bombing of the World Trade Center.” Will Potter, Green Is The New Red: An Insider's Account of a Social Movement Under Siege, City Lights, 2011, p58 (based on Christine Haughney, ‘Teenagers' Activism Takes a Violent Turn - New York Youths Linked to Ecoterrorist Group’, Washington Post, 27 March 2001.). The New York JTTF, comprising Federal and local law enforcement agencies, was the lead for the 1993 WTC attack, and the point of liaison for foreign detectives, such as Bob Lambert, assisting the inquiry. Given Lambert's career-defining two areas of expertise - animal rights/environmental anarchists and Islamic radicals - it seems possible that he would retain contact with NYJTTF over the years as a professional courtesy, given its own interest in those same two topics.

- ↑ The National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, The 9/11 Commission Report, W. W. Norton & Company, 22 July 2004 (accessed 22 March 2015), p162.

- ↑ Robert Lambert, ‘What if Bin Laden had stood trial?’, The Guardian, 3 May 2011 (accessed 22 November 2014).

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Robert Lambert & Jonathan Githens-Mazer, Islamophobia and Anti-Muslim Hate Crime: UK Case Studies 2010 - An introduction to a ten year Europe-wide research project (first edition) (research project) European Muslim Research Centre/University of Exeter, November 2010 (accessed via counterextremism.org 11 June 2014).

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Robert Lambert & Jonathan Githens-Mazer, Islamophobia and Anti-Muslim Hate Crime: UK Case Studies 2010 - An introduction to a ten year Europe-wide research project (second edition) (research project), European Muslim Research Centre/University of Exeter, January 2011 (accessed via archive.org 11 June 2014).

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber/Guardian Books, 2013, p55.

- ↑ Chief Constable Mick Creedon, Operation Herne - Report 2: Allegations of Peter Francis (second edition), Derbyshire Constabulary, 2014, p22 (accessed 16 April 2014).

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Andy Davies, ‘"We did not target Stephen's family", says undercover boss’, Channel 4 News, 1 July 2013 (accessed 16 March 2014).

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber/Guardian Books, 2013, p81.

- ↑ Mark Ellison QC, The Stephen Lawrence Independent Review: Volume One, Home Office, March 2013 (accessed 1 April 2014), p213.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedART007p235 - ↑ Derbyshire Constabulary, Operation Herne - Report 3: Special Demonstration Squad Reporting - Mentions of Sensitive Campaigns, Derbyshire Constabulary, July 2014, pp8-9 (accessed 21 November 2014).

- ↑ Private source, August 2014.

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013, pp57-58.

- ↑ Chief Constable Mick Creedon, Operation Herne - Report 1: Use of covert identities, Derbyshire Constabulary, 2013, p8 (accessed 16 April 2014).

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber/Guardian Books, 2013, p158.

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013, p82.

- ↑ Mark Ellison QC, Stephen Lawrence review: volume 1, HMSO, 2014 (accessed 16 April 2014), p226.

- ↑ Mark Ellison QC, Stephen Lawrence review: volume 1, HMSO, 2014 (accessed 16 April 2014), p227.

- ↑ BBC News, ‘Stephen Lawrence: Chronology of events’, BBC News, 25 March 1999 (accessed 18 February 2015).

- ↑ Mark Ellison QC, Stephen Lawrence review: volume 1, HMSO, 2014, p251 (accessed 16 April 2014).

- ↑ Mark Ellison QC, Stephen Lawrence independent review: summary of findings, HMSO, 2014 (accessed 16 April 2014).

- ↑ Mark Ellison QC, Stephen Lawrence review: volume 1, HMSO, 2014 (accessed 16 April 2014).

- ↑ Mark Ellison QC, Stephen Lawrence review: volume 2, part 1, HMSO, 2014 (accessed 16 April 2014).

- ↑ Mark Ellison QC, Stephen Lawrence review: volume 2, part 1, HMSO, 2014 (accessed 16 April 2014).

- ↑ Derbyshire Constabulary, Operation Herne - Report 3: Special Demonstration Squad Reporting - Mentions of Sensitive Campaigns, Derbyshire Constabulary, July 2014(accessed 21 November 2014).

- ↑ See, for example, Bob Lambert, ‘Reflections on Counter-Terrorism Partnerships in Britain’, Arches, issue number 5, January-February 2007 (accessed 22 November 2014) - this biography notes that “Bob worked continuously as a Special Branch specialist counter-terrorist / counter-extremist intelligence officer from 1980” until the setting up of MCU at the beginning of 2002.

- ↑ Bob Lambert, ‘Reflections on Counter-Terrorism Partnerships in Britain’, Arches, issue number 5, January-February 2007 (accessed 22 November 2014).

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda in London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, Hurst & Company, 2011, p35.

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber/Guardian Books, 2013, p57

- ↑ Lambert's account in both his book and CSTPV profile is that MCU was founded by himself and one other colleague; the Evans/Lewis book claims Lambert “and two other former SDS spies were given the resources to set up the Muslim Contact Unit.” Subsequent clarification from Evans to the author is that his understanding is that MCU was conceived and set up by Lambert and one other former SDS officer. The accounts all agree that MCU was established in the aftermath of 9/11 in January 2002. Source CAVALVANTI (who has some familiarity with Lambert's academic reinvention) has added to the author that the actual foundation of MCU came, to paraphrase Lambert's own words, “following discussions in October-November 2001”. It has been speculated that Lambert's cohort in creating MCU was Jim Boyling (e.g. merrick, ‘bob lambert: still spying?’, Bristling Badger, 23 February 2012), who elsewhere has been acknowledged as involved in the unit (e.g. Paul Lewis & Rob Evans, ‘Police spy tricked lover with activist 'cover story'’, The Guardian, 23 October 2011; Paul Lewis, Rob Evans & Rowenna Davis, ‘Ex-wife of police spy tells how she fell in love and had children with him’, The Guardian, 19 January 2011; and Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013, p194). However, it is the author's understanding that whilst Boyling was and remains a close friend of Lambert's, he was not co-creator with Lambert of MCU, though he was an early recruit to the unit.

- ↑ Paul Sims, ‘Crossing the line?’, New Humanist, 4 November 2011 (accessed 3 February 2015).

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda in London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, Hurst & Company, 2011, p55.

- ↑ Cheryl Benard, Civil Democratic Islam: Partners, Resources and Strategies, RAND Corporation, 2003 (accessed 16 April 2014).

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 111.2 111.3 111.4 Robert Lambert, Staff profile page, Handa Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence, University of St. Andrews website, 2012 (accessed 19 April 2014).

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Robert Lambert, London Metropolitan University (accessed 3 April 2014).

- ↑ It should be noted that Lambert implies an association with the University of Exeter from September 2005 - see the reference in his book to “commenc[ing] regular train journeys from Paddington [in central London] to Exeter St. David's” in that month. Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda in London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, Hurst & Company, 2011, p.xvi.

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Staff profile page, John Grieve Policing Centre, London Metropolitan University website, 2013 (accessed 19 April 2014).

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 London Metropolitan University, Course Handbook: BSc (Hons) Criminology and Law (2012-2013), London Metropolitan University, 2012 (accessed 9 March 2015).

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 London Metropolitan University, Course Handbook: BA (Hons) Criminology and Law (2013-2014), London Metropolitan University, 2013 (accessed 9 March 2015).

- ↑ The University of Exeter has never satisfactorily explained the ending of its relationship with Bob Lambert. It was only in January 2015 that The Guardian was able to report that the university “confirmed that Lambert resigned from the university in October 2011 - the same month his undercover past was exposed.” As journalist Rob Evans notes, “We asked Exeter University why he resigned but, after some delay, they refused to explain.” See: Rob Evans, ‘University under pressure to sack controversial former undercover spy Bob Lambert’, The Guardian, 6 January 2015 (accessed 9 March 2015).

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda In London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, C Hurst & Co, 2011, p390.

- ↑ European Muslim Research Centre, ‘Staff’, University of Exeter (via archive.org), 8 June 2012 (accessed 3 April 2014).

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 120.2 Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda in London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, Hurst & Company, 2011.

- ↑ Dr Jonathan Githens-Mazer & Dr Robert Lambert MBE, Islamophobia and Anti-Muslim Hate Crime: A London Case Study'' (research project), European Muslim Research Centre/University of Exeter, January 2010 (accessed via counterextremism.org 16 April 2014).

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 Robert Lambert, ‘Researching counterterrorism: a personal perspective from a former undercover police officer’. Critical Studies on Terrorism Volume 7 Number 1, pp165-181 (2014).

- ↑ For example, see the inclusion of “Muslim Contact Unit SO15” in the note of “organisations represented in the audience” in this invitation list for a March 2010 Cordoba-hosted debate at which Lambert was a key participant: Cordoba Foundation, Tackling Islamophobia - Reducing Street Violence Against British Muslims, notice of debate organised by Cordoba Foundation, 3 March 2010 (accessed 21 November 2014).

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 Paul Hutcheon, ‘St Andrews University called on to sack former police sex spy Bob Lambert’, Sunday Herald, 13 December 2015 (accessed 26 March 2016).

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 Department of Politics, ‘Mr Robert Lambert’, University of Exeter (via archive.org), 24 September 2010 (accessed 3 April 2014).

- ↑ Department of Politics, ‘Dr Robert Lambert’, University of Exeter (via archive.org), 24 April 2011 (accessed 3 April 2014).

- ↑ European Muslim Research Centre, ‘News’, University of Exeter website (via archive.org), 15 August 2010 (accessed 16 March 2014).

- ↑ European Muslim Research Centre, ‘EMRC homepage’, University of Exeter website (via archive.org), 16 February 2012 (accessed 16 March 2014).

- ↑ University of Exeter Press Office, ‘Counter terrorism research published’, University of Exeter, 7 September 2011 (accessed 18 February 2015).

- ↑ European Muslim Research Centre, ‘Staff’, EMRC website (via archive.org), 8 June 2012 (accessed 16 March 2014).

- ↑ European Muslim Research Centre, ‘Staff’, EMRC website (via archive.org), 29 August 2012 (accessed 16 March 2014).

- ↑ 132.0 132.1 Rob Evans, ‘University under pressure to sack controversial former undercover spy Bob Lambert’, The Guardian, 6 January 2015 (accessed 9 March 2015).

- ↑ That Lambert began work at St. Andrews University in September 2008 is obliquely corroborated by the reference in his book to “commenc[ing] regular train journeys from...Kings Cross [in central London] to Leuchars” - the nearest rail station to St. Andrews - in that month. See Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda in London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, Hurst & Company, 2011, p.xvi.

- ↑ Handa Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence staff page, ‘Sir David Veness’, University of St. Andrews website (accessed 16 April 2014).

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 London Metropolitan University, ‘About us (2015 version)’, London Metropolitan University website, 2015? (accessed 22 March 2015).

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 London Metropolitan University, ‘About us (2013 version)’, London Metropolitan University website, 2013 (accessed 22 March 2015).

- ↑ Malcolm Gillies, ‘July 2013 Staff Newsletter from the Vice-Chancellor’, London Metropolitan University website, 26 July 2013 (accessed 22 March 2015).

- ↑ Whilst Lambert is named as course leader in the 2012-13 and 2013-14 prospectuses, in the 2014-25 one he has been supplanted by Devinder Curry. London Metropolitan University, Course Handbook: BA (Hons) Criminology and Law (2014-2015), London Metropolitan University, 2014 (accessed 9 March 2015).

- ↑ MPS backgrounds: Tim Fairley, John Grieve and Nick Ridley. Anti-Terrorist Branch: John Grieve and Nick Ridley. MPSB: Nick Ridley. St. Andrews University Terrorism Studies: Tim Fairley and Douglas Weeks. EMRC: Tim Parsons. Source: London Metropolitan University, ‘About us (2015 version)’, London Metropolitan University website, 2015? (accessed 22 March 2015).

- ↑ Joseph Cassidy, ‘Bob Lambert resigns as University lecturer over spying controversy’, The Saint, 22 December 2015 (accessed 31 January 2016).

- ↑ Paul Hutcheon, ‘Former undercover police officer Bob Lambert quits St Andrews University teaching post over outcry’, The Herald, 23 December 2015 (accessed 26 March 2016).

- ↑ Rob Evans, ‘Ex-undercover officer who infiltrated political groups resigns from academic posts’, The Guardian, 23 December 2015 (accessed 26 March 2016).

- ↑ Chris Havergal, ‘Former undercover police officer resigns academic posts’, Times Higher Education, 23 December 2015 (accessed 26 March 2016).

- ↑ William McLennan, ‘Lecturer who faced protests over ‘police spy’ past, hands in his notice at Holloway Road university’, Islington Tribune, 30 December 2015 (accessed 26 March 2016).

- ↑ Comment is Free, ‘Robert Lambert (profile page)’, The Guardian, 2011 (accessed 29 April 2015).

- ↑ As an approximate guide, in the years 2007-2011 Lambert had nine articles published by academic journals; since his outing only one more - and that dealt, if obliquely, with his public unmasking (see: Robert Lambert, ‘Researching counterterrorism: a personal perspective from a former undercover police officer’. Critical Studies on Terrorism Volume 7 Number 1, pp165-181 (2014).) Similarly, compared to thirty-six articles attributed to Lambert's authorship which were published by newspapers, magazines or websites prior to his exposure, only six more have come out since October 2011. (Count accurate to March 2016.)

- ↑ The author previously delved into this aspect of Lambert's life in a series of blog posts. See: BristleKRS, ‘On cop-spies and paid betrayers (1.2): Doctor Bob Lambert, his academic friends and the tightening purse-strings’, Bristle's Blog From The BunKRS, 6 September 2012 (accessed 18 April 2015); and BristleKRS, ‘On cop-spies and paid betrayers (1.3): Lambert of the Yard and the mystery of his ‘suburban terror bunker’ trading address’, Bristle's Blog From The BunKRS, 8 September 2012 (accessed 18 April 2015).

- ↑ Anthony [Abdul Haqq] Baker, Countering Terrorism in the UK: A Convert Community Perspective, University of Exeter, University of Exeter, November 2009 (accessed 18 November 2014), p330.

- ↑ Baker notes at n1121 in his doctoral thesis that the first draft of the proposal outlining what would become STREET was dated 16 June 2006. See: Anthony [Abdul Haqq] Baker, Countering Terrorism in the UK: A Convert Community Perspective, University of Exeter, University of Exeter, November 2009 (accessed 18 November 2014), p326.

- ↑ Rachel Briggs, Catherine Fieschi & Hannah Lownsbrough, Bringing it Home: Community-based approaches to counter-terrorism, DEMOS, December 2006 (accessed 16 April 2014), pp75-76.

- ↑ Abdul Haqq Baker, Dr Abdul Haqq Baker staff profile page, -, 2012 (accessed 18 April 2015).

- ↑ Anthony [Abdul Haqq] Baker, Countering Terrorism in the UK: A Convert Community Perspective, University of Exeter, University of Exeter, November 2009 (accessed 18 November 2014), p160.

- ↑ Jack Barclay, Strategy to Reach, Empower, and Educate Teenagers (STREET): A Case Study in Government-Community Partnership and Direct Intervention to Counter Violent Extremism, Center on Global Counterterrorism Cooperation, December 2011(accessed 21 November 2014).

- ↑ Companies House, STRATEGY TO REACH EMPOWER AND EDUCATE TEENAGERS (STREET UK) LIMITED, Companies House (via CompanyCheck.co.uk), 2012 (accessed 18 April 2015).

- ↑ Companies House, ROBERT LAMBERT, Companies House (via CompanyCheck.co.uk), 2012 (accessed 18 April 2015).

- ↑ Companies House, ABDUL HAQQ BAKER, Companies House (via CompanyCheck.co.uk), 2012 (accessed 18 April 2015).

- ↑ STREET was set up as a company on 6 May 2008, it was nearly two weeks - before any directors were appointed: Lambert on 18 May and Dr Abdul Haqq Baker on 19 May.

- ↑ See Lambert's career timeline for contextualisation.

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda in London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, Hurst & Company, 2011, pp155-156.

- ↑ Palgrave Macmillan, ‘About the Author: Abdul Haqq Baker’, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011 (accessed 18 April 2015).

- ↑ Curiously, Baker himself points towards the failure of the police investigation into the 1993 murder of Stephen Lawrence (“and ensuing ineptitude”) as highly pre-eminent amongst the “negative pre-conversion experiences” of many black (and some white) British muslim converts, who then “continue to view statutory authorities and governmental agencies with mistrust.” Quite how he now sees Lambert's own involvement in subverting the Macpherson Inquiry and various family and justice campaigns through his work as SDS manager and facilitator of the meeting between Richard Walton and Brixton-based undercover officer ‘N81’ remains to be seen. See: Anthony [Abdul Haqq] Baker, Countering Terrorism in the UK: A Convert Community Perspective, University of Exeter, University of Exeter, November 2009 (accessed 18 November 2014), p331.

- ↑ Companies House, LAMBERT CONSULTANCY AND TRAINING LIMITED, Companies House (via CompanyCheck.co.uk), 2012 (accessed 6 September 2012).

- ↑ Details about Lambert's company can be corroborated by searching the official Companies House website at companieshouse.gov.uk. The company number is 06678759.

- ↑ 164.0 164.1 Duncan Gardham, ‘Counter-terrorism projects worth £1.2m face axe as part of end to multiculturalism’, Daily Telegraph, 11 February 2011 (accessed 17 April 2015).

- ↑ Companies House, SIRAAT LTD, Companies House (via CompanyCheck.co.uk), 2012 (accessed 18 April 2015).

- ↑ Companies House, SIRAAT LTD, Companies House (via DueDil.com), 2015 (accessed 18 April 2015).

- ↑ Companies House, STREET CONSULTANCY LIMITED, Companies House (via CompanyCheck.co.uk), 2015 (accessed 18 April 2015).

- ↑ Companies House, INITIATIVE FOR MUSLIM PROGRESSION & ADVANCEMENT OF COMMUNITY TOLERANCE (IMPACT) LIMITED, Companies House (via CompanyCheck.co.uk), 2015 (accessed 18 April 2015).

- ↑ Communities and Local Government Committee, Preventing Violent Extremism: Sixth Report of Session 2009-20, HMSO, 16 March 2010 (accessed 22 April 2015).

- ↑ Martin Bright, When Progressives Treat with Reactionaries, Policy Exchange (via archive.org), July 2006 (accessed 18 March 2014).

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda In London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, C Hurst & Co, 2011, p31 plus notes 2-5, p308.

- ↑ Catriona Mackie, ‘City Police launch 'Guide to Islam'’, City of London Police, July 2006 (accessed via Archive.org 18 April 2015).

- ↑ unknown author, ‘Police officers issued with guide to Islam’, Daily Mail, 5 July 2006 (accessed 9 March 2015).

- ↑ Press Association, ‘Police given 'Guide to Islam' to improve relations with London Muslims’, 24dash.com, 5 July 2006 (accessed 22 March 2015).

- ↑ 175.0 175.1 Hadi Yahmid, ‘True Islam Image in London Conf.’, On Islam, 24 November 2007 (accessed 22 March 2015).

- ↑ 176.0 176.1 unknown author, ‘Islam Expo 2008: Building Bridges of Understanding’, Islamic Tourism, July 2008 (accessed 22 March 2015).

- ↑ 177.0 177.1 Innovative Minds, ‘Islamic Human Rights Commission 2007: A Decade of Fighting Injustice’, Innovative Minds, November 2007 (accessed 3 February 2015).

- ↑ Robert Lambert, Countering Al-Qaeda in London: Police and Muslims in Partnership, Hurst & Company, 2011, p241.

- ↑ London Greenpeace, ‘Undercover police agent publicly outed at conference’, Indymedia UK, 15 October 2011 (accessed 15 March 2014).

- ↑ Stopinfiltration@mail.com, The truth about Bob Lambert and his Special Branch role, Indymedia UK, 15 October 2011 (accessed 23 April 2014).

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber/Guardian Books, 2013, pp59-61; 331-332.