Difference between revisions of "Alfred Sherman"

(→Affiliations) |

m (→Affiliations) |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

===Early years=== | ===Early years=== | ||

| − | Sherman was born on 10 November 1919 to Jacob Vladimir Sherman and Eva (née Goldental). <ref>‘[http://www.ukwhoswho.com/view/article/oupww/whowaswho/U34693 SHERMAN, Sir Alfred]’, ''Who Was Who'', A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007, [Accessed 10 Dec 2009]</ref> Both his parents | + | Sherman was born on 10 November 1919 to Jacob Vladimir Sherman and Eva (née Goldental). <ref>‘[http://www.ukwhoswho.com/view/article/oupww/whowaswho/U34693 SHERMAN, Sir Alfred]’, ''Who Was Who'', A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007, [Accessed 10 Dec 2009]</ref> Both his parents were Russian Jewish immigrants. His father was a tailor and a Labour Party councillor. <ref>Jonathan Glancey, '[http://www.guardian.co.uk/g2/story/0,,395350,00.html G2: The Tory: Alfred Sherman]', ''Guardian'', 10 November 2000</ref> |

Sherman attended Hackney Downs County Secondary School in North London and subsequently began studying Chemistry at the Chelsea Polytechnic. At that stage Sherman was a communist and at the age of 17 he abandoned his studies served in the International Brigade in the Spanish Civil War. <ref>both cited in Sir Alfred Sherman, ''Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude'' (Imprint Academic, 2005); | Sherman attended Hackney Downs County Secondary School in North London and subsequently began studying Chemistry at the Chelsea Polytechnic. At that stage Sherman was a communist and at the age of 17 he abandoned his studies served in the International Brigade in the Spanish Civil War. <ref>both cited in Sir Alfred Sherman, ''Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude'' (Imprint Academic, 2005); | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

<blockquote style="background-color:ivory;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%;font-size:10pt">By 1983 [[Hugh Thomas|Lord Thomas]] (the historian [[Hugh Thomas]]), who had been appointed chairman of the CPS in 1979, was finding Sherman impossible to work with. In the summer of that year, following a row over the relationship of the CPS with the Tory party, Sherman was summarily sacked from the CPS in a ‘virulent’ letter from Thomas.<p>Sherman did not blame Thomas personally, but criticised ‘changed attitudes among Conservative leaders towards ideas, once back in office’, typically adding, ‘the effects on the CPS of de-Shermanisation are painfully evident in the brain death inflicted.’<ref>‘[http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1527400/Sir-Alfred-Sherman.html Sir Alfred Sherman]’, ''Daily Telegraph'', 28 August 2009</ref></p></blockquote> | <blockquote style="background-color:ivory;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%;font-size:10pt">By 1983 [[Hugh Thomas|Lord Thomas]] (the historian [[Hugh Thomas]]), who had been appointed chairman of the CPS in 1979, was finding Sherman impossible to work with. In the summer of that year, following a row over the relationship of the CPS with the Tory party, Sherman was summarily sacked from the CPS in a ‘virulent’ letter from Thomas.<p>Sherman did not blame Thomas personally, but criticised ‘changed attitudes among Conservative leaders towards ideas, once back in office’, typically adding, ‘the effects on the CPS of de-Shermanisation are painfully evident in the brain death inflicted.’<ref>‘[http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1527400/Sir-Alfred-Sherman.html Sir Alfred Sherman]’, ''Daily Telegraph'', 28 August 2009</ref></p></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Policy Search=== | ||

| + | Sir Alfred Sherman was reported as 'chairman of Policy-Search, an independent policy studies centre' at the end of an article he wrote in the ''Guardian'' in April 1987. <ref>Alfred Sherman, 'The Third Term: Policies and politics in the election balance - Series on the Conservative future', ''Guardian'', 8 April 1987.</ref> [[Policy Search]] was a small 'short lived' <ref>Peter Osborne, Tom Leonard, 'Lone John's silver; The Redwood Foundation goes in search of big money', ''Evening Standard'', 27 September 1995; p.15.</ref> think tank based in 14 [[Tufton Street]] in Westminster in the late 1980s. It seems to have been active only between 1987 and 1989. It provided a base for [[Christopher Monckton]]. <ref>Christopher Monckton, ''The Aids Report: An examination of public health policy on AIDS'', London: [[Policy Search]], 14 [[Tufton Street]], Westminster, SW1, May 1987.</ref> | ||

==Views== | ==Views== | ||

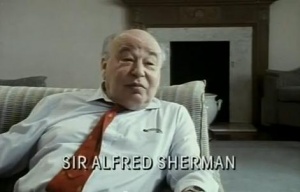

| + | [[File:Sherman.JPG|thumb|300px|right|Alfred Sherman in Adam Curtis's 1992 documentary ''Pandora's Box''.]] | ||

Sherman was a fanatical neoliberal and was extremely hostile, not only to trade unionists and social democrats, but also to most of the political establishment. According to the ''Guardian'' he ‘seemed to despise most politicians and civil servants’ <ref>‘[http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/2006/aug/29/guardianobituaries.conservatives Sir Alfred Sherman – Adviser who preached Thatcherism before the term was invented]’, ''Guardian'', 29 August 2006</ref> According to Mark Garnett he viewed civil servants as ‘inveterate empire-builders, who would resist radical reform until they had been stripped of the last briefcase and bowler hat.’ <ref>Sir Alfred Sherman, ''Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude'' (Imprint Academic, 2005); | Sherman was a fanatical neoliberal and was extremely hostile, not only to trade unionists and social democrats, but also to most of the political establishment. According to the ''Guardian'' he ‘seemed to despise most politicians and civil servants’ <ref>‘[http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/2006/aug/29/guardianobituaries.conservatives Sir Alfred Sherman – Adviser who preached Thatcherism before the term was invented]’, ''Guardian'', 29 August 2006</ref> According to Mark Garnett he viewed civil servants as ‘inveterate empire-builders, who would resist radical reform until they had been stripped of the last briefcase and bowler hat.’ <ref>Sir Alfred Sherman, ''Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude'' (Imprint Academic, 2005); | ||

[http://www.imprint.co.uk/books/sherman-Preface_and_foreword.pdf Preface, by Norman Tebbit & Editor’s Foreword, by Mark Garnett], p.7</ref> The ''Sunday Telegraph'' once described Sherman as an ‘ego-maniacal, spiteful, obsessive, prone to temper tantrums which would disgrace a three-year-old’. <ref>quoted in John Barnes, ‘[http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/sir-alfred-sherman-414683.html Sir Alfred Sherman – Political adviser to Thatcher]’, ''Independent'', 5 September 2006</ref> Sherman was so extreme that he eventually alienated all of his Conservative allies. In his memoirs, ''Conflict of Loyalty'', [[Geoffrey Howe]] describes Sherman as a ‘zealot’, suggesting that ‘good ideas all too often lost their charm in the light of the zeal with which he espoused them.’ <ref>cited in Sir Alfred Sherman, ''Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude'' (Imprint Academic, 2005); | [http://www.imprint.co.uk/books/sherman-Preface_and_foreword.pdf Preface, by Norman Tebbit & Editor’s Foreword, by Mark Garnett], p.7</ref> The ''Sunday Telegraph'' once described Sherman as an ‘ego-maniacal, spiteful, obsessive, prone to temper tantrums which would disgrace a three-year-old’. <ref>quoted in John Barnes, ‘[http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/sir-alfred-sherman-414683.html Sir Alfred Sherman – Political adviser to Thatcher]’, ''Independent'', 5 September 2006</ref> Sherman was so extreme that he eventually alienated all of his Conservative allies. In his memoirs, ''Conflict of Loyalty'', [[Geoffrey Howe]] describes Sherman as a ‘zealot’, suggesting that ‘good ideas all too often lost their charm in the light of the zeal with which he espoused them.’ <ref>cited in Sir Alfred Sherman, ''Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude'' (Imprint Academic, 2005); | ||

| Line 44: | Line 48: | ||

==Affiliations== | ==Affiliations== | ||

| − | + | [[Centre for Policy Studies]], co-founder 1974-1983 | |

| + | <br>[[Policy Search]], Chair and founder 1987-89 | ||

| + | <br>[[Gideon Sherman]], son | ||

| + | <br>[[Lord Byron Foundation for Balkan Studies]] - co-founded this research institute in 1994 | ||

==Resources== | ==Resources== | ||

Latest revision as of 03:10, 16 June 2015

Sir Alfred Sherman (10 November 1919 - 26 August 2006) was a journalist and neoliberal activist best known for co-founding the Centre for Policy Studies with Margaret Thatcher and Keith Joseph.

Contents

Biography

Early years

Sherman was born on 10 November 1919 to Jacob Vladimir Sherman and Eva (née Goldental). [2] Both his parents were Russian Jewish immigrants. His father was a tailor and a Labour Party councillor. [3]

Sherman attended Hackney Downs County Secondary School in North London and subsequently began studying Chemistry at the Chelsea Polytechnic. At that stage Sherman was a communist and at the age of 17 he abandoned his studies served in the International Brigade in the Spanish Civil War. [4] He told the Guardian: 'My politics were driven by emotion. That's how you see the world at 17. It's all black and white, painted in broad brushstrokes. I was studying chemistry at the time at Chelsea Polytechnic. I was appalled by the rise of fascism, followed the civil war in the papers and wanted to do my bit.' [5] He wrote in his memoirs: 'As a communist, I learned to think big, to believe that, aligned with the forces of history, a handful of people of sufficient faith could move mountains. [6]

Sherman later experienced an ‘ideological conversion’. According to Mark Garnett, who worked with Sherman on his memoirs, ‘Instead of subsiding towards the Right in easy stages, he soon became an indefatigable freemarket crusader.’ [7] Sherman’s sudden departure from communism is thought to have occurred in 1948, whilst he was studying at the London School of Economics. According to the Daily Telegraph Sherman was president of the student Communist Party but was expelled when he refused to amend a paper on Tito following his split with Stalin. [8] He told the Guardian: 'I was expelled for attacking Stalin over Yugoslavia, and much else beside... Communism and socialism were walls that stood in front of me after the Hitler war. I took them down brick by brick until I could see the clear light beyond.' [9]

Journalism

After graduating Sherman spent a short period as a teacher and then reportedly wrote for the Observer and the Jerusalem Post in Israel. According to the Independent, ‘It was in Israel that he developed a taste for advising on free market economics, becoming an adviser to the General Zionists Party.’ [10] During the 1950s Sherman was also a member of the economic advisory staff of the Israeli Government. [11]

From 1959 to 1986 he worked as a journalist in London, first at the Jewish Chronicle (1959–70) and then concurrently as a leader writer, and subsequently the London correspondent of the Israeli daily Al-Haaretz (1961–75). He also held various appointments at the Daily Telegraph from 1965 to 1986, and was the paper’s leader writer from 1977. [12]

Keith Joseph and the Centre for Policy Studies

It was whilst a local government reporter for the Daily Telegraph that Sherman first met the Conservative politician and neoliberal campaigner Keith Joseph. [13] In 1969 Sherman drafted some of Joseph's speeches celebrating free market doctrine. [14] According to Mark Garnett, Joseph ‘learned to defer to Sherman’s intellectual authority’ and by the time they co-founded the Centre for Policy Studies, ‘Sherman had begun to act as Joseph’s tutor and psychological prop’. [15]

Sherman co-founded the CPS with Joseph and Thatcher in 1974. According to the Independent, Sherman ‘had conceived of the CPS as a political organisation designed to give the ideas formulated by the Institute of Economic Affairs political force’. [16] According to the Guardian: ‘In those “heroic” days it was little more than an office employing Sherman to draft speeches for Joseph. It attracted a number of people who had not been active Tories but became influential later, notably David Young (later Lord Young of Graffham) and John (later Sir) Hoskyns.’ [17]

Mark Garnett writes that, ‘by 1983 Hoskyns, Strauss and Sherman had either departed or become disillusioned, because in their view the government had been too timid in its approach both to institutions and to policies.’ [18] The Daily Telegraph gives the following account of Sherman’s departure from the Centre for Policy Studies:

By 1983 Lord Thomas (the historian Hugh Thomas), who had been appointed chairman of the CPS in 1979, was finding Sherman impossible to work with. In the summer of that year, following a row over the relationship of the CPS with the Tory party, Sherman was summarily sacked from the CPS in a ‘virulent’ letter from Thomas.

Sherman did not blame Thomas personally, but criticised ‘changed attitudes among Conservative leaders towards ideas, once back in office’, typically adding, ‘the effects on the CPS of de-Shermanisation are painfully evident in the brain death inflicted.’[19]

Policy Search

Sir Alfred Sherman was reported as 'chairman of Policy-Search, an independent policy studies centre' at the end of an article he wrote in the Guardian in April 1987. [20] Policy Search was a small 'short lived' [21] think tank based in 14 Tufton Street in Westminster in the late 1980s. It seems to have been active only between 1987 and 1989. It provided a base for Christopher Monckton. [22]

Views

Sherman was a fanatical neoliberal and was extremely hostile, not only to trade unionists and social democrats, but also to most of the political establishment. According to the Guardian he ‘seemed to despise most politicians and civil servants’ [23] According to Mark Garnett he viewed civil servants as ‘inveterate empire-builders, who would resist radical reform until they had been stripped of the last briefcase and bowler hat.’ [24] The Sunday Telegraph once described Sherman as an ‘ego-maniacal, spiteful, obsessive, prone to temper tantrums which would disgrace a three-year-old’. [25] Sherman was so extreme that he eventually alienated all of his Conservative allies. In his memoirs, Conflict of Loyalty, Geoffrey Howe describes Sherman as a ‘zealot’, suggesting that ‘good ideas all too often lost their charm in the light of the zeal with which he espoused them.’ [26] Mark Garnett writes that, ‘Margaret Thatcher wanted to re-write the political rule-book; but Alfred Sherman wanted to see it burn.’ [27]

In the prologue to Sherman’s biography, Norman Tebbit writes that Sherman was not simply an economic liberal, but was ‘extremely aware that free market capitalism is a tool, not an objective’. According to Tebbit, Sherman like Thatcher believed that, ‘family and civilised values are the foundation on which the nation and its economy are built.’ [28]

Sherman was also a racist. In 1992, when secret Soviet archives were opened, it emerged that in 1984 Sherman had given an interview to Pravda in which he was quoted as saying: ‘As for the lumpen, coloured people and the Irish, let's face it, the only way to hold them in check is to have enough well armed and properly trained police.’ [29] After his death, his former colleague at the Daily Telegraph, Edward Pearce, wrote to the Independent to say that: ‘The word “racist” is over-used,’ but, ‘Alfred Sherman was the real thing.’ Pearce wrote: ‘I recall two particular remarks from editorial conference: “the American Negro army” (said in furious contempt) and “Where I was brought up, there was Irish all round and we knew they was inferior”.’ [30]

Affiliations

Centre for Policy Studies, co-founder 1974-1983

Policy Search, Chair and founder 1987-89

Gideon Sherman, son

Lord Byron Foundation for Balkan Studies - co-founded this research institute in 1994

Resources

Sir Alfred Sherman, Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude (Imprint Academic, 2005); Preface, by Norman Tebbit & Editor’s Foreword, by Mark Garnett

Notes

- ↑ quoted in John Barnes, ‘Sir Alfred Sherman – Political adviser to Thatcher’, Independent, 5 September 2006

- ↑ ‘SHERMAN, Sir Alfred’, Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007, [Accessed 10 Dec 2009]

- ↑ Jonathan Glancey, 'G2: The Tory: Alfred Sherman', Guardian, 10 November 2000

- ↑ both cited in Sir Alfred Sherman, Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude (Imprint Academic, 2005); Preface, by Norman Tebbit & Editor’s Foreword, by Mark Garnett, p.4

- ↑ Jonathan Glancey, 'G2: The Tory: Alfred Sherman', Guardian, 10 November 2000

- ↑ quoted in Andy Beckett, When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies (London: Faber & Faber, 2009) p.280

- ↑ Sir Alfred Sherman, Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude (Imprint Academic, 2005); Preface, by Norman Tebbit & Editor’s Foreword, by Mark Garnett, p.4

- ↑ ‘Sir Alfred Sherman’, Daily Telegraph, 28 August 2009

- ↑ Jonathan Glancey, 'G2: The Tory: Alfred Sherman', Guardian, 10 November 2000

- ↑ John Barnes, ‘Sir Alfred Sherman – Political adviser to Thatcher’, Independent, 5 September 2006

- ↑ ‘SHERMAN, Sir Alfred’, Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007, [Accessed 10 Dec 2009]

- ↑ ‘SHERMAN, Sir Alfred’, Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007, [Accessed 10 Dec 2009]

- ↑ ‘Sir Alfred Sherman – Adviser who preached Thatcherism before the term was invented’, Guardian, 29 August 2006; Sir Alfred Sherman, Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude (Imprint Academic, 2005); Preface, by Norman Tebbit & Editor’s Foreword, by Mark Garnett, p.5

- ↑ ‘Sir Alfred Sherman – Adviser who preached Thatcherism before the term was invented’, Guardian, 29 August 2006

- ↑ Sir Alfred Sherman, Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude (Imprint Academic, 2005); Preface, by Norman Tebbit & Editor’s Foreword, by Mark Garnett, p.5

- ↑ John Barnes, ‘Sir Alfred Sherman – Political adviser to Thatcher’, Independent, 5 September 2006

- ↑ ‘Sir Alfred Sherman – Adviser who preached Thatcherism before the term was invented’, Guardian, 29 August 2006

- ↑ Sir Alfred Sherman, Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude (Imprint Academic, 2005); Preface, by Norman Tebbit & Editor’s Foreword, by Mark Garnett, p.8

- ↑ ‘Sir Alfred Sherman’, Daily Telegraph, 28 August 2009

- ↑ Alfred Sherman, 'The Third Term: Policies and politics in the election balance - Series on the Conservative future', Guardian, 8 April 1987.

- ↑ Peter Osborne, Tom Leonard, 'Lone John's silver; The Redwood Foundation goes in search of big money', Evening Standard, 27 September 1995; p.15.

- ↑ Christopher Monckton, The Aids Report: An examination of public health policy on AIDS, London: Policy Search, 14 Tufton Street, Westminster, SW1, May 1987.

- ↑ ‘Sir Alfred Sherman – Adviser who preached Thatcherism before the term was invented’, Guardian, 29 August 2006

- ↑ Sir Alfred Sherman, Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude (Imprint Academic, 2005); Preface, by Norman Tebbit & Editor’s Foreword, by Mark Garnett, p.7

- ↑ quoted in John Barnes, ‘Sir Alfred Sherman – Political adviser to Thatcher’, Independent, 5 September 2006

- ↑ cited in Sir Alfred Sherman, Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude (Imprint Academic, 2005); Preface, by Norman Tebbit & Editor’s Foreword, by Mark Garnett, p.4

- ↑ Sir Alfred Sherman, Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude (Imprint Academic, 2005); Preface, by Norman Tebbit & Editor’s Foreword, by Mark Garnett, p.9

- ↑ Sir Alfred Sherman, Paradoxes of Power - Reflections on the Thatcher Interlude (Imprint Academic, 2005); Preface, by Norman Tebbit & Editor’s Foreword, by Mark Garnett, p.1

- ↑ ‘Sir Alfred Sherman’, Daily Telegraph, 28 August 2009

- ↑ ‘OBITUARIES: Sir Alfred Sherman’, Independent, 18 September 2006; p.35