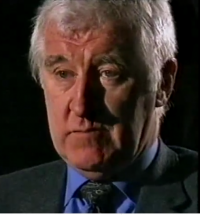

Wilf Knight

This article is part of the Undercover Research Portal at Powerbase - investigating corporate and police spying on activists

Wilfred Victor Robert 'Wilf' Knight was born on May 24, 1944. A Metropolitan Police and Special Branch officer, who also worked in the secretive undercover unit the Special Demonstration Squad, which is currently being investigated by a public inquiry. In 2002, in the tv documentary True Spies, he claimed that he supervised one such officer Mike Ferguson, who infiltrated the anti-apartheid movement. The disclosure of the Undercover Policing Inquiry makes this claim doubtful.

Knight retired from the Metropolitan Police in 1986 after 27 years. Later, he formed his own company - Robert Gregory Associates, which merged with private security and intelligence company C2i International. He died on March 14, 2008, at the age of 63.[1] This profile addresses his police career, a detailed account of his private security career is forthcoming.

1968 onwards: Special Branch & Intelligence gathering

In 1960, Knight joined the Metropolitan Police's Special Branch. This included roles as a personal protection officer and a variety of jobs where his responsibilities involved gathering intelligence on political activists.[2] A part of the Metropolitan Police's Special Branch’s remit was to deal with 'subversive activities’, ‘those which threaten the safety or well-being of the State, and which are intended to undermine or overthrow parliamentary democracy by political, industrial or violent means'.[3]

Interviews with Wilf Knight in a 2002 BBC documentary, True Spies about MI5 and Special Branch suggested that Knight had an intelligence gathering role from around 1968. Knight commented on the 1968 Anti-Vietnam war protests outside the U.S. Embassy in London:[4]

- We underestimated how many were coming. We were ill-equipped at the time and couldn't bring enough men in to control it; consequently, when the violence erupted. We were amateurs then, link arms and hold them . They just kicked the fertiliser out of you.[5] The recognition was that we were totally inept at both the information we gathered and the way we dealt with that information.

However, his precise role is not specified, other than the clear implication that he was working for Special Branch at this point.

1968 - 1971 Special Demonstration Squad

In the wake of the 1968 protests against the American involvement in the Vietnam war, an undercover unit was set up to infiltrate these new social movements. First going by the name of Special Operations Squad, it later changed into Special Demonstration Squad (SDS). This unit is one of two main undercover police units which are the central focus of the Undercover Policing Inquiry.[6][4][7] Correspondingly, many of the first SDS infiltrators were tasked to enter groups involved in the Vietnam Solidarity Committee.

- More background on the undercover police who targeted the anti-Vietnam War protests can be found in the Undercover Research Group profiles of John Graham, Bill Lewis, Dick Epps, HN322, Don de Freitas , and Margaret White (all names are aliases).[7]

- For more on Special Branch and the Anti-Vietnam War Protests, see: 1968: Protest and Special Branch.

Police Career

Knight had a 27-year career in the Metropolitan Police, first training as a cadet in 1959 when he attended Hendon Police College as a 15-year-old and retiring as a Superintendent in 1986.[2]

Late 60s: Knight's Revelations in True Spies

Some of the information used in this profile (including above) was taken from interview material contained In True Spies, a BBC documentary broadcast in 2002 which addressed the issue of secret political policing in Britain. In fact, Knight's words gave the series its name:[4]

- They [the undercover police officers] had a complete new personality created for them, new names, new addresses, new apartments, new driving licenses, new social security numbers. They just were wiped off the face of the earth as far as police identification went. They were ‘true spies, true spies.'

Prior to the discovery of the later NPIOU officers in 2011 by activists, and the latter publication (by the Undercover Policing Inquiry) of the Special Demonstration Squad Tradecraft manual, this was one of the first hints on how undercover officers within this unit operated.[8][9]

Knight described the Special Demonstration Squad:[4]

- We called them the 'hairies' because they all grew their hair long down to their shoulders. A policeman wasn't short back and sides like the marines anymore. These guys wore hair down to their shoulders and looked like Jesus Christ incarnate and changed dramatically.

Knight explains how a group of 'very brave, dedicated officers' had personalities created for them and ‘went out to work in the field undercover totally divorced from their friends, their family, and they literally worked their way into organisations’, comparing them to the Special Air Service (SAS) in the military.[10]

Bugging Tariq Ali

Knight also revealed a widespread phone tapping and electronic bugging operation mounted against political campaigners from the late 1960's onwards:[11][4]

- There was a government building, not far from the House of Commons. It was called 'the bunker'. It was the most miserable place on earth. It was the nearest thing to a subterranean underground car park building you've ever seen, and that's where we sat with just taps and banks and banks of tape recorders running all the time, and that's all you did. You just tapped those kind of people, people high up who were the organisers, the brains I mean I suppose you could call them.

Peter Taylor, the presenter of the BBC programme asked whether Tariq Ali, a prominent political campaigner and writer was surveilled in this way, to which Knight replied: 'Tariq Ali was tapped for a long time but then you see Tariq Ali was never afraid of either the publicity or the notoriety which he obtained'.[4]

This seems to suggest that Knight thought that Ali deserved to be bugged just due to his roles in radical politics. Special Branch documents revealed that a magazine - Black Dwarf', edited by Tariq Ali, (1968-1970) had been of interest to them since 1968.[12] (On 10 July 2018, Tariq Ali was accepted as a core participant in the Undercover Policing Inquiry.)[13]

Illegal Bugging

True Spies made the point that telephone tapping had to be done with government authority, which at the time were known as Home Office Warrants (HOWs). In contrast, the direct placing of electronic 'bugs' was not governed by any statutory regulation.[14] Knight commented:[4]

- Sometimes you simply drilled a hole through the wall, and stuck a probe through and tried to listen to what they were saying I remember drilling with the connivance of the hotel, drilling a hole through a wall in a hotel in West London where a meeting was going to take place, and we drilled through 15 inches taking four days working at night to get into this meeting room and we finally struck a girder which was supporting the whole of the hotel ...we… sometimes I wasn't very professional. You were outside of the law, lets understand that. You were working outside of the law. You just did it because you happened to believe that this is a wonderful country worth living in and you were trying to keep it clean and democratic, and maybe we were dirty ourselves.

1970: Supposed Handler of Mike Ferguson - and spying on the anti-apartheid movement

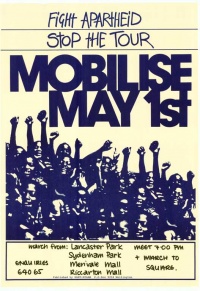

1970 was a pivotal year, both internationally and in the UK for the anti-apartheid movement. At this point, South Africa was expelled from the Olympic movement and in the UK a sporting boycott was called for in cricket and rugby.[15]

A recent commentator describes it thus:[16]

- When the Springbok [white South African] side had arrived for the rugby tour in the winter, the campaign had dogged them at every step. From chants and marches, to running into the grounds and sit ins, to cuffing themselves to the goal posts or climbing them, to locking players in the hotel rooms to hijacking their team bus, the young, long-haired brigade had done everything to ensure that the cricket tour did not follow.[17]

In the 2002 BBC documentary series True Spies, Knight was introduced as 'the handler' (or cover officer) of one of the first SDS infiltrators to target the anti-apartheid movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[4] An 'agent handler' or 'cover officer', liaised with those police who were undercover, to debrief and collect information as well as to monitor the well-being of those deployed and manage interactions between undercover officers (UCO's) and the operational team.[18][19][20] In his True Spies interview, Knight also revealed the name of one of the undercover officers whom he claimed to have supervised: Mike Ferguson, who infiltrated the Anti-apartheid movement in 1970.

True Spies was made with the permission of the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police and might therefore be considered a PR piece for the secret state rather than a accurate account. Meanwhile, others within Special Branch were unhappy with what the programme revealed, especially in regard to revealing Mike Ferguson's name. (For more on the making of True Spies, see Eveline Lubbers, BBC True Spies Series: Police happy to cisclose information when it suits them, 24 March 2016 SBF.uk.)

Years later, Clare Carson, who has written a trilogy of novels loosely based on her relationship with her father - a undercover policeman - also stated publicly that her dad was the officer in the SDS who was named in True Spies.[21] According to The Guardian, this was his real, rather than cover name, subsequently confirmed by the Undercover Policing Inquiry in late 2019, which also announced that they intended to withhold his cover name.[22][4][23]

In the extensive disclosure of this period that the Undercover Policing Inquiry has made, the only document relating to Knight was the transcript to True Spies. This means that Knight was never in the SDS, and likely only knew of Ferguson's infiltration through Special Branch gossip and/or later working with him.[24] Moreover, at the time of Knight's supposed involvement, around 1970, undercover officers were debriefed at a safe house on a weekly basis. However, they did not have 'handlers'.[25]

A full analysis of Wilf Knight's account on Ferguson and the infiltration of the anti-apartheid movement are covered in Mike Ferguson's profile.

1971-1975: Personal Protection

Knight was a personal protection officer (bodyguard) to two Prime Ministers.[2] Personal protection officers were normally of junior rank - this suggests that this episode should be placed relatively early on in Knight's Special Branch career.[26] During this period, Edward Heath (1970-1974) and Harold Wilson (1974-1976) were Prime Minister. Knight carried out the same role regarding several foreign heads of state: King Hussein of Jordan; Presidents Banda of Malawi, Nyerere of Tanzania, Kaunda of Zambia and Seretse Kama of Botswana.[27] Additionally, Knight was officer in charge of body guarding government ministers in Belfast for three years.[2]

1975-1977(?): Anti-Terrorist Branch

Knight spent 2-years in the anti-terrorist branch (ATB) (Originally 'The Bomb Squad', later S013) where he was one of the early negotiators in hostage situations.[2] This makes it likely that Knight was deployed to the ATB when the need for hostage negotiators was recognised in 1976.[28][29]

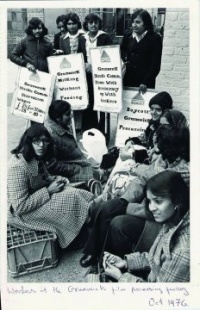

1976-1977: Back to Special Branch: The Grunwick Industrial Dispute

On 23 August 1976, a small number of workers who were predominantly female and South Asian began picketing the Grunwick Photo Processing Laboratories in North London. They were protesting poor working conditions and the management’s refusal to address their grievances. By the time the strike ended, some of the more radical wing of the British Trade Union movement has joined the struggle, including, significantly, the National Union of Mineworkers and its leader Arthur Scargill.[30][31]

Again, in True Spies, Wilf Knight outlined his role at the strike:[4]

- We became spotters, and you would literally go along to some of the more violent demonstrations. At Grunwick, it was our job to go and see who was associating and organising small bands of anarchists and left-wing people to be attacking the police. You went up looking as scruffy and dirty and as unkempt as they were. We weren't ‘hairies', but we certainly didn't go out in pinstripe suits with our club ties on...So you'd do a couple of days up there and then you'd come away and you'd write up all your notes on who you saw, who they were with, what cars they were with, where they were coming from.

The fact that Knight says 'we weren't hairies' indicates that he was not present as an undercover with the SDS, which the nickname 'the hairies' refers to (see below). Rather, it is likely that he would be involved with the Industrial Desk within Special Branch.

However, former Special Branch Officers, Wilson and Adams in their book ‘History of Special Branch’ say that the SDS was also present in the strike and supplied ‘up-to-date information on what the [police] were likely to encounter’ at the Grunwick Industrial Dispute (1976-1978).[32] The context of this remark suggests that it was one of the many infiltrators into the Socialist Workers Party.[33] This information was passed on by the senior officer of the SDS, notably, the senior officer at this time may have been Mike Ferguson.[32]

A small number of police documents were released regarding the Grunwick dispute and corroborate Knight's recollections of Special Branch interest. An in-depth analysis of these documents is available here and here.

It was at this point that Knight's Special Branch career came to a conclusion.[2]

1977-1980: Cambridge University & Bramhill Police College

In 1977, Knight attended Bramhill Police College, for officer training, apparently chosen for an accelerated police career path.[34][2]

And between 1977 and 1980 Wilf Knight studied Archaeology and Anthropology at Trinity College, Cambridge. He gained a Masters (MA) degree - the length of time he spent studying suggests that he did it on a part-time basis, whilst continuing working as a police officer.[2]

1980-1983: Community Policing, Brixton Uprising, and Police Racism

Community Policing. Between 1980 and 1983, Wilf Knight was a Detective Chief Inspector serving in the A7 (Community Relations) division of the Metropolitan Police. While 'Community Relations', or 'Community Policing' had been the a part of British policing since the 1960s, it took on a new prominence after the inner city riots of the early 1980s.[35]

However, it might be thought that Knight's previous career path within Special Branch would have not given him the experience, or mindset needed for community policing at such a senior level. Notably, another, later, police officer, Bob Lambert, switched from a undercover intelligence role to a supposedly community orientated civic role. When his earlier undercover role (coupled with his unethical behaviour - he had a long-term relationship and fathered a child) this lead people to question the real motivation with his work with Muslim communities.[36] Correspondingly, it might therefore be questionable whether Knight saw his main role as community relations, or intelligence gathering.

Brixton Uprising. In the early 1980s, there was a series of inner-city riots across England.[37] Often the cause for the riots was the experience with oppressive and racist policing: these factors were especially apparent in Brixton in 1981.

At the beginning of April that year, the Metropolitan Police began 'Operation Swamp 81', a plain-clothes operation to supposedly reduce crime. Uniformed patrols were also significantly increased in the area by dispatching officers from other Metropolitan police district into Brixton. The notorious Special Patrol Group was brought in as well.[38]

Within five days, 943 people were stopped and searched, and 82 arrested, through the heavy use of what was colloquially known as the ‘Sus law.’[39] Many members of the African-Caribbean community testified that the police were disproportionately using these powers against black people.[40] On 10th April 1981, a riot broke out that would last three days.[40]

At the time of the Brixton riot, Knight had been in 'Community Relations' for about a year.[41][42][43]

In 1981, Knight was called by the Scarman Inquiry investigating the Brixton riots, to explain his role in the events.[44]

In his statement, Knight repeats what is often the official reasoning behind issues with public order - that they are caused by 'outsiders’, or are a result of a political conspiracy:[44]

- It was significant to me that there were young white individuals and some black who were there apparently solely for the purpose of inciting young black youths to do the damage. I actually came across one white male who attempted to coerce a crowd of mainly black youths to storm the Police Station on the pretext that blacks [sic] were being beaten up there.

Later in the statement, Knight describes a failed attempt to pacify the situation:[44]

- I had spoken to a group of Rastafarians who agreed to set up a sound system (band) with police co-operation opposite the adventure playground in Railton Road. This was between 6.30 and 7pm. The music lasted about an hour until the stones started flying causing the band to pick up their instruments and run. This incident appeared to be caused by the large black man (sic) earlier referred to appearing on the scene berating everyone there saying this is not a police inspired carnival [sic], this is our revolution.

When asked about the cause for the riots, Knight refers to an inter-generational divide within the black communities in Brixton.[44] Against this, other commentators have suggested additional context. For instance, as well as being less accepting of institutional and other form of racism than earlier generations of those who had migrated from Britain's former colonies, it was black youth in Brixton, as elsewhere in the UK, who bore the brunt of aggressive and discriminatory policing of the time.[45]

Thesis on Police Racism. Knight submitted his thesis for his Cambridge MPhil to Trinity College, Cambridge in 1983. The subject matter of his dissertation was police racism, dovetailing with his role in Community Relations and its emphasis on 'race relations'.[46] His supervisor at Cambridge, Professor Colin Sumner expands:

- His research topic was racism in the Met. Wilf had carried out a survey of racist attitudes amongst his colleagues at the Met and the results were appalling and disturbing. He sent out around 650 questionnaires, with the express backing, if I remember rightly, by [an] accompanying letter, of the Metropolitan Commissioner himself, and amazingly, about 350 officers actually refused to respond, despite its authoritative nature. Many of those who did respond, although not all by any means, expressed the crudest form of racism you could imagine. As Wilf's supervisor, of course I saw many of these returned questionnaires and was dismayed by the frequent reference to monkeys swinging from the trees and other colonial crudities.[47]

Again according to Sumner, Knight's thesis was placed on 'restricted access' in the Cambridge University Library at his own request. Knight told Sumner that due to its 'explosive' content ‘any public disclosure would likely result in him being 'promoted' to some police training outpost in the Orkneys.’[47] Cambridge University have said that they did not retain a copy of the dissertation as it did not receive a distinction.[48] Also, in 1982, Knight had a academic journal article published: Solvent Abuse - the Role of the Police.[49]

1984-1985: Superintendent at Leman Street Police Station, Miners Strike and Retirement

Wilf Knight was promoted to the rank of Superintendent and retired as such. His last post was as Assistant Officer in charge at Leman Street Station, Tower Hamlets in the East End of London between 1984 and 1985.[50]

Retirement. Knight retired from the Metropolitan Police in 1986. Anecdotally, a colleague of Knight's in the private security industry, Sims, quoted above, said that Knight was forced to retire on medical grounds following injuries sustained when trying to help a colleague during the 1984 Miner's Strike.[51] No independent sources can verify whether Knight was indeed, present at any of the picket lines during the miners strike, although being a Superintendent, it seems strange that he would have such a frontline role.[52]

1986-2008 Post-Police Career

Following his retirement from the MPS in 1986, Knight immediately entered the world of private security founding his own company Robert Gregory Associates, before joining another company C2i International. As mentioned, a separate profile dealing with Knight’s second career is forthcoming.

Knight died on March 14, 2008, at the age of 63. [1]

Education

- Watford Boys Grammar School

- Police College, Hendon (1959-60)

- Police College, Bramshill College (1977-76)

- Trinity Cambridge University. MA Archaeology/Anthropology (1977-80)

- Trinity College, Cambridge. DPhil Criminology, (Bramshill Police Fellowship) (1982-83)[2]

Advised films on intelligence issues

During and after his career in the Met, Knight functioned as a specialist consultant to feature films on British Law enforcement, intelligence and terrorist activity. His biography on IMDB says he is known for his work on: The Bill (1984), The Media Show (1987) and Hidden Agenda (1990) - a Ken Loach film he did alongside Fred Holroyd.[1] He also helped Harrison Ford with the Patriot Games (1992).[53]

In the Undercover Policing Inquiry

To date, the Undercover Policing Inquiry has not released any files regarding Knight, even though he had an important role at the back office. There seems to be no HN number attached to him, or it has not been released yet. As he is deceased and has apparently not been an undercover officer himself, there was no procedure to protect his identity. His real name was already in the public domain after his appearance in True Spies.

He is not on the draft list of witnesses that was published on the 9 September 2020 for the evidence hearings of Tranche 1 (covering the period 1968-1982) of the Inquiry. That said, most managers are still only referred to by their 'nominals' (or HN number) on that list, rather than by name.[54]

Nevertheless, Knight has been mentioned several times in the preliminary hearings for the Inquiry, in submissions of others. In one instance, the use of open source material by independent journalists and researchers that referred to Wilf Knight’s dual career as a police officer and then as a security consultant are used as an argument for total anonymity for two of the MPS officers.[55] A rebuttal of this argument by one of the non-state participants, Dónal O’Driscoll also references Knight.[56]

O’Driscoll also used Knight’s dual role within the public and private spheres to argue for the inclusion of former undercover officer’s private industry careers in the remit of the Undercover Policing Inquiry’s terms of reference.[57]

Notes

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 Wilf Knight, Internet Movie Database (IMDb.com), undated (accessed September 2016).

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Wilf Knight Document, 27 June 2007 (accessed 20 March 2018).

- ↑ Home Office, Guidelines on the work of a Special Branch 1984 (accessed 29 August 2019).

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 True Spies, Episode 1 BBC, 2002 (accessed 11 October 2020).

- ↑ Note: Quaint euphemism for 'shit'.

- ↑ Conrad Dixon (obituary), The Times, 28 April 1999 (accessed 21 July 2019 via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Dónal O’Driscoll, 1968 – Protest and Special Branch 14 April 2018 (accessed 23 July 2019).

- ↑ Undercover Research Group, Was My Friend A Spycop?, UndercoverResearch.net, 2017 (accessed 23 July 2019).

- ↑ Andy Coles, SDS Tradecraft Manual 1995 (accessed 24 July 2019).

- ↑ Note: It was an exaggeration to say they were ‘totally divorced’ from their family and friends, as undercover officers did have time away from their deployment to visit friends and family.

- ↑ Note: It is not entirely clear what period Knight is referring to when discussing the electronic surveillance, though it is mentioned in the context of spying upon Tariq Ali who was active from 1968 onwards

- ↑ See: Dónal O’Driscoll, 1968 – Protest and Special Branch part 5: Additional Material: Black Dwarf investigated for incitement by Special Branch, '’SpecialBranchFiles.uk’’, 14 April 2018 (accessed 25 July 2019).

- ↑ Sir John Mitting, Recognised Legal Representatives Costs of Legal Representation Awards - Ruling 15, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 10 July 2019 (accessed 25 July 2019).

- ↑ Christopher Andrew, THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SECRET SERVICE BUREAU, MI5.gov.uk, undated, (accessed 25 July 2019).

- ↑ Forward to Freedom: A History of the Anti-Apartheid Movement.Don't scrum with a Racist Bum' accessed 30 July 2019).

- ↑ Adrian Runswick, 50 years of Stop The Seventy Tour Campaign: New book to relive the drama, cricmash.com, 21 May 2020 (accessed 9 October 2020).

- ↑ Note: South Africa’s all-white rugby board had close links with the British rugby establishment. In the 1970s and 1980s they worked together to break the boycott.

- ↑ Note: From 1996, the cover officer would also pass intelligence to ‘C’ Squad (which dealt with so-called ‘Domestic Extremism’ - previously known as 'subversion') within Special Branch. Mick Creedon, Operation Herne – Report 2 2014 (accessed 28 August 2019).

- ↑ College of Policing, Supervision of Undercover Operatives 2015 (accessed 27 August 2019).

- ↑ College of Policing UCA Self-assessment and questionnaire 2015 (accessed 27 August 2019).

- ↑ Clare Carson, My dad, the undercover policeman, The Guardian, 26 May 2015 (accessed 17 Sep 2020).

- ↑ John Mitting Ruling 16. 29 October 2019 (accessed 9 December 2019).

- ↑ Note: According to Clare Carson, her father Mike Ferguson left the SDS as head officer, and took on other roles within the Metropolitan Police. He died in 1999.

- ↑ Index to bundle on HN 103, HN 1251, HN 3093, HN 3095 HN 325, HN 474, PN 1748 Undercover Policing Inquiry, 16 May 2022.

- ↑ Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary, Inspection of Undercover Policing in England and Wales 2015 (accessed 29 August 2019).

- ↑ Ray Wilson and Ian Adams, Special Branch: A History 1883-2006, Biteback Publishing, 2015, pages 73-77.

- ↑ Note: The longevity of these leader’s reigns, premierships and presidencies do not allow for more accurate pinpointing Knight’s time in personal protection: King Hussein (Reign: 1952-1999) Presidents Banda of Malawi (1964 to 1994), Nyerere of Tanzania (1964 to 1985) and Kaunda of Zambia (1964 to 1991) and Seretse Kama Botswana (1966 to 1980).

- ↑ Note: A training course in hostage negotiation was integrated into the Metropolitan Police's Hendon College shortly after the Balcombe Street and Spaghetti House sieges, with the role of hostage (or ‘crisis’) negotiator formally adopted in 1976. See: National Policing Improvement Agency, The Use of Negotiators by Incident Commanders 2011 (accessed 27 August 2019) and Steven P. Moysey Chapter 7: Observations on the Balcombe Street Siege, Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations, 8:2, 245-261 2008 (accessed 31 July 2019).

- ↑ Note: Special Branch and The Anti-Terrorist Branch have always had a close relationship. The Bomb Squad was originally set up in 1971 to catch 'The Angry Brigade’, who also were a target of Special Branch. In fact, the Bomb Squad was made up of two sections, one from the Criminal Investigations Department (CID) and the other from Special Branch of the Metropolitan Police, with the latter headed originally be Conrad Dixon. See: Ray Wilson and Ian Adams, Special Branch: A History 1883-2006. BiteBack Publishing, pp.259-260, 2013 (accessed 23 October 2020). Also, in 2005, Special Branch and The Anti-Terrorist Branch merged. See: Martin Bright, The Observer Look back in anger (accessed 4 September 2019).

- ↑ Jac St John, Grunwick Dispute – Story, SpecialBranchFiles.uk, 4 March 2016 (accessed 30 July 2019).

- ↑ The Grunwick Dispute, Striking-Women.org, undated, (accessed 31 July 2019).

- ↑ Jump up to: 32.0 32.1 Ray Wilson and Ian Adams, Special Branch: A History 1883-2006, Biteback Publishing, 2015, page 307.

- ↑ Note: Adams and Wilson state, before stating that the SDS supplied useful information, state: 'As always, the extremist organisations, in this case particularly the Socialist Workers Party, strove to turn what was a peaceful picket into a confrontation with athe police'. The infiltrators whose cover name is in the public domain and are said to have infiltrated the SWP at this time are: Jeff Slater, Bob Stubbs, Gary Roberts], Roger Harris, Geoff Wallace, Vince Miller, Billy Biggs, Colin Clark, Michael James], and Paul Gray.

- ↑ Wesley Kerr, The ever-flowing stream , The Fountain, Trinity College Newsletter, Spring 2010 (accessed September 2019).

- ↑ Halil Ibraham Kavgaci, The Development of Police/Community Relations Initiatives in England and Wales Post Scarman and Their Relevance to Policing Policy in Turkey (doctoral thesis), Leicester University, 1995.

- ↑ Basia Spalek and Mary O’Rawe, Researching counterterrorism: a critical perspective from the field in the light of allegations and findings of covert activities by undercover police officers, Critical Studies on Terrorism, 2014 (accessed 21 October 2010).

- ↑ Note: The use of the term 'uprising' (as opposed to 'riot') has been used by both those who were involved at the time as well as black historians and social commentators to emphasis its political, as opposed to criminal nature. However, as the rest of the discussion is within a policing context, we shall revert to riot.

- ↑ Note: The Special patrol Group was a specialist public order division of the Metropolitan Police. There successor units are now known as the Territorial Support Group. The SPG was implicated in the murder of anti-racist campaigner Blair Peach. See: Paul Lewis, Blair Peach killed by police at 1979 protest, Met report finds, ‘’The Guardian’’, 27 April 2010 (accessed 10 December 2019).

- ↑ Note: This referred to powers under the Vagrancy Act 1824, which allowed police to search and arrest members of the public when it was believed that they were acting suspiciously, (but not necessarily committing a crime).

- ↑ Jump up to: 40.0 40.1 Metropolitan Police Brixton Riots 1981 (accessed 28 August 2019).

- ↑ Chief Inspector Wilfred Victor Knight, P.S. 44 TNA: HO 266/96.

- ↑ Note: The 1981 Police Gazette lists him as Superintendent in 1981, but as a Detective Chief Inspector 1982-83 which is a rank below Superintendent, so likely to be a mistake. See: Police Gazette 1981, Police Gazette 1982, Police Gazette 1983.

- ↑ Lawrence Roach, The Metropolitan Police Community Relations Branch. See: Police Studies: The International Review of Police Development, 1(3), 17-23. (accessed 27 August 2019).

- ↑ Jump up to: 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 Detective Chief Inspector Wilfred Victor Knight, P.S. 44 TNA: HO 266/96.(accessed 31 July 2019).

- ↑ Tony Jefferson, Policing the riots: from Bristol and Brixton to Tottenham, via Toxteth, Handsworth, etc 14 March 2012 (accessed 21 October 2020).

- ↑ Poor Community Relations Community Policing - National Criminal Justice Reference Library, Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1980 (accessed 21 October 2020).

- ↑ Jump up to: 47.0 47.1 Colin Sumner, Racism in the Met: memories from the 1980's, CrimeTalk.org, 4 January 2012 (accessed 31 July 2019).

- ↑ Eveline e-mail

- ↑ Detective Chief Inspector Wilfred Knight, Solvent Abuse - the Role of the Police Human Toxicology, Volume: 1 issue: 3, page(s): 345-346 1 July 1982 (accessed 10 August 2019).

- ↑ Police Gazette 1985 Document Cloud, 1985 (accessed 17 September 2020).

- ↑ Brian Sims, Wilf Knight (1944-2008): a tribute, Security Management Today, IFSEC Global website, 2008 (accessed September 2016).

- ↑ Note: According to official figures, only four officers from the Metropolitan Police were injured up to July 1984 (after Orgreave). See: Home Office Letter to Michael Portillo 10 July 1984 (accessed 5 September 2019).

- ↑ Brad Duke, Harrison Ford: The Films, McFarland & co, 2005, p. 178.

- ↑ Provisional List of UCOs and Civilians whose evidence is to be considered in Tranche 1 Phase 1 ‘20200908_JW_NPSCP_Response_To_Queries.pdf’, attached to Letter from James Wilson, Inquiry Solicitor to Lydia Dagostino, Coordinator to the Non-State Core Participant lawyers, 9 September 2020.

- ↑ Neil Hutchinson, Statement Number 5, Metropolitan Police Service, (accessed 31 July 2019 via ucpi.org.uk).

- ↑ Dónal O’Driscoll, Statement, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 16 September 2016 (accessed 31 July 2019).

- ↑ Dónal O'Driscoll, Third Witness statement, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 18 November 2018 (accessed 31 July 2019).