Robert Armstrong

Lord Robert Temple Armstrong, Baron Armstrong of Ilminster is a former civil servant. Armstrong was educated at Eton College and Christ Church College, Oxford University. He was with the Treasury between 1950 and 1964, and Reginald Maudling's principal private secretary (PPS). He held the office of assistant secretary of the cabinet office between 1964 and 1966, the office of assistant secretary of Treasury between 1967 and 1968, when he was Roy Jenkins' PPS, joint PPS to the Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1968, under-secretary of the Treasury between 1968 and 1970, PPS to the prime minister between 1970 and 1975, deputy undersecretary to the Home Office between 1975 and 1977, and private undersecretary to the Home Office between 1977 and 1979. From 1979 to 1987, he served as secretary of the Cabinet under prime minister Margaret Thatcher.

He was invested as a Knight Commander, Order of the Bath (K.C.B.) in 1978 and was invested as a Knight Grand Cross, Order of the Bath (G.C.B.) in 1983.

He was a director of N M Rothschild & Sons in 1988, a director of Shell Transport and Trading in 1988, a director of BAT Industries between 1988 and 1997 and was created a Baron in 1988. He was a director of the Bank of Ireland in 1991 and a director of Carlton TV between 1991 and 1995, Bristol & West Building Society 1988-, Inchcape 1988-, Lucas Industries 1989-92, RTZ Corporation 1988-, Chairman Biotechnical Investments Ltd since 1989, and member of Robeco Group 1988-. He held the office of Chancellor of Hull University in 1994.[1]

Contents

Attempt to prosecute anti-apartheid activist: 1973

Declassified files state that Armstrong, while principal private secretary to Prime Minister Edward Heath, wrote to the Attorney General's office in September 1973 in an attempt to invoke a little-used criminal libel proceedings to prosecute Peter Hain, who was at that time a thorn in the government's side over his activities with the anti-apartheid movement.[2] Hain had been a target of BOSS, the South African Secret Intelligence Service, since 1968 and they planned to set him up and discredit his activities, which they did.[3]According to BOSS's Gordon Winter these activities included aid from the Society for Individual Freedom, which he describes as a British Intelligence front involving George K. Young, Ross McWhirter (both with UK intelligence connections) and Gerald Howarth.[4]This is taken up by Hain himself in his account of being framed for bank robbery.[5] The Armstrong letter may well be connected to this given his membership of the Institute for the Study of Conflict.

Thatcher's closest adviser: 1979

According to the Civil Service website, Armstrong, as the new secretary to UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher's Cabinet, "effortlessly took on the role as her most senior closest official adviser"[6]. This was despite that fact that:

- The arrival of Margaret Thatcher’s government in the corridors of Whitehall in May 1979 was the biggest jolt that the Civil Service had experienced in living memory. For a while the whole Whitehall system almost visibly juddered... It was a culture shock. The elite administrative grade of the Civil Service in Whitehall has come to think of itself as the guardian and trustee of national continuity...The Prime Minister and a small group of sympathetic ministers...were arguing that its ideas and advice had proved bankrupt, that now was the time for an entirely new approach.[7]

Anglo-Irish negotiations: 1982

According to Jonathan Powell in his book Great Hatred, Little Room, Making Peace in Northern Ireland, Armstrong played a role in Northern Ireland peace talks in 1982:

- The first tentative contacts between the British and the Irish took place in 1982. David Goodall, a senior British diplomat attached to the Cabinet Office, from a Catholic family with connections to Ireland, began talking to Michael Lillis, a senior Irish diplomat, ferociously clever and with staunch republican antecedents. The NIO disapproved of the whole exercise and, as a result, was largely kept out of the loop. The negotiations were conducted in great secrecy with Goodall joined by the Cabinet Secretary Robert Armstrong on the British side and Lillis joined by another senior Irish diplomat, Sean Donlon, along with Dermot Nally, the Irish Cabinet Secretary.[8]

Snuffing out the public interest

In the 1980s there was debate about the extent of civil servants' duty towards the government and whether it should overrule any duty to the wider public. This was prompted by the case of Clive Ponting, the civil servant who in 1984 leaked information to an MP about the sinking of the Argentine Navy ship, the Belgrano, by the British during the Falklands War two years previously, killing 360 people. The government had claimed that the Belgrano was threatening British lives when it was sunk. But the document leaked by Ponting indicated that it was sailing away from the Royal Navy taskforce, and was outside the exclusion zone, when it was attacked and sunk.[9]

The publication of this information was a massive embarrassment for Thatcher's government. Ponting was prosecuted under the Official Secrets Act of 1911, which prohibited revealing confidential information but allowed the defence that revealing the information was in the public interest.[10] Ponting used the public interest defence in court and the jury acquitted him in spite of the judge's direction to convict.

On 25 February 1985 Armstrong, in his role as Head of the Civil Service and Secretary to the Cabinet, produced a memorandum on the duties and responsibilities of civil servants to Ministers. The memorandum, which has become known as the Armstrong Memorandum, stated that Servants of the crown meant servants of the government of the day. Armstrong stated:

- Civil servants are servants of the Crown. For all practical purposes the Crown in this context means and is represented by the Government of the day... Civil Service as such has no constitutional personality or responsibility separate from the duly elected Government of the day.[11]

In early 1986 the Thatcher government was rocked by another scandal involving the leaking of information – the Westland affair. Westland was a struggling British helicopter manufacturer which was the subject of Cabinet-level discussions about the choice between two different rescue packages: one European and the other American. Information from these discussions was leaked to the press in an affair that led to the resignation of the then defence secretary Michael Heseltine. Armstrong led the inquiry into one of the leaks. He concluded that trade and industry secretary Leon Brittan had told chief information officer of the department of trade and industry, Colette Bowe, to leak a letter written by the solicitor-general Patrick Mayhew to Heseltine.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Thatcher government revised the Official Secrets Act in 1989, removing the public interest defence by repealing Section 2.

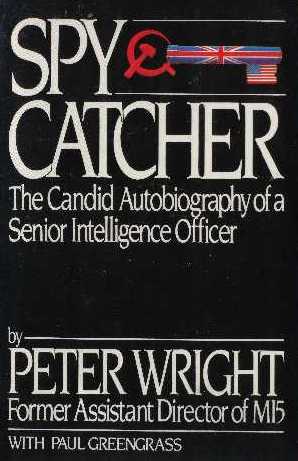

Spycatcher

Armstrong, who retired as head of the Civil Service in late 1987, is credited with coining a memorable phrase (others credit Edmund Burke[12]) in 1986 when cross-examined in the supreme court in New South Wales during the Australian 'Spycatcher' trial:

- Lawyer: What is the difference between a misleading impression and a lie?

- Armstrong: A lie is a straight untruth.

- Lawyer: What is a misleading impression - a sort of bent untruth?

- Armstrong: As one person said, it is perhaps being "economical with the truth".[13]

Declassified files state that Armstrong, while principal private secretary to Prime Minister Edward Heath, wrote to the Attorney General's office in September 1973 in an attempt to invoke a little-used criminal libel proceedings to prosecute Peter Hain, who was at that time a thorn in the government's side over his activities with the anti-apartheid movement.[14] Hain had been a target of BOSS, the South African Secret Intelligence Service, since 1968 and they planned to set him up and discredit his activities, which they did.[15]According to BOSS's Gordon Winter these activities included aid from the Society for Individual Freedom, which he describes as a British Intelligence front involving George K. Young, Ross McWhirter (both with UK intelligence connections) and Gerald Howarth.[16]This is taken up by Hain himself in his account of being framed for bank robbery.[17] The Armstrong letter may well be connected to this given his membership of the Institute for the Study of Conflict.

References

- ↑ All biographical information is from "Person page 4448", ThePeerage.com website, accessed January 2009

- ↑ "Hain libel threat shown in papers", BBC News, 20 August 2004, accessed January 2009

- ↑ Gordon Winter (1981) Inside Boss, Penguin, p370

- ↑ Gordon Winter (1981) Inside Boss, Penguin, p382-383

- ↑ Peter Hain (1987) A Putney Plot, p146-147, Spokesman.

- ↑ "The evolution of the United Kingdom Civil Service 1848-1997", Civil Service website, February 2007, accessed January 2009

- ↑ "The evolution of the United Kingdom Civil Service 1848-1997", Civil Service website, February 2007, accessed January 2009

- ↑ Great Hatred, Little Room, Making Peace in Northern Ireland by Jonathan Powell,The Bodley Head, 2008, p59.

- ↑ "Troubled history of Official Secrets Act", BBC News, 18 November 1998, accessed January 2009

- ↑ For more information on this defence, see "Public Interest Defence", Hansard, HC Deb 22 February 1989 vol 147 cc1036-50, accessed January 2009.

- ↑ Robert Armstrong, The Duties and Responsibilities of Civil Servants in Relation to Ministers, cited in "The evolution of the United Kingdom Civil Service 1848-1997", Civil Service website, February 2007, accessed January 2009

- ↑ "Economical with the truth", Phrase Finder website, accessed January 2009

- ↑ "Economical with the truth", Phrase Finder website, accessed January 2009

- ↑ "Hain libel threat shown in papers", BBC News, 20 August 2004, accessed January 2009

- ↑ Gordon Winter (1981) Inside Boss, Penguin, p370

- ↑ Gordon Winter (1981) Inside Boss, Penguin, p382-383

- ↑ Peter Hain (1987) A Putney Plot, p146-147, Spokesman.