Rick Gibson (alias)

This article is part of the Undercover Research Portal at Powerbase - investigating corporate and police spying on activists

Rick Gibson is the alias of a former Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) undercover police officer. He was active for two years between 1974 - 1976, when he infiltrated the South East London branch of the Troops Out Movement (TOM) and took on roles at the national level in the organisation. He then sought to become a member of Big Flame, but his lack of political background caused suspicion. Big Flame found out that Gibson had lied about his background and was using the identity of a deceased child. Confronted with these finding in 1976, ‘Gibson’ disappeared; and the story was never published.

In the BBC series True Spies, Peter Taylor interviewed an undercover in disguise about infiltrating the TOM. Watching it in 2002, Richard Chessum, who had founded the South East London chapter of the organisation with Gibson amongst others, thought he recognised his former comrade. He wrote a six-page letter to Taylor detailing his memories of the undercover and how he was exposed.[1] This letter is used here as the basis for the profile of Rick Gibson.

The cover identity and the groups Rick Gibson reported on were revealed by the Undercover Policing Inquiry in August 2017.[2] He is also referred to by the cypher 'HN297', for the purposes of the Inquiry.

'N297 returned to the SDS later in his career in a non-undercover role.' He also worked in close protection duties at some point after ending his deployment as an undercover.[3]

Update November 2017

At the November hearing of the Undercover Policing Inquiry, the Undercover Research Group revealed that Gibson had been in at least two, but maybe four relationships with women. It was clear that the Inquiry nor the police knew anything about this. The Chair immediately understood the importance of evidence that targeting women had been a practice from very early on. More detail below.

- Eveline Lubbers, 'Rick Gibson' - #spycops sexually targeted women from the start, URG blogpost, 28 November 2017.

- Rob Evans, How a Met police spy's fake identity was rumbled, The Guardian, 28 November 2017

Update February 2018.

Mary, one of the women who had been in a relationship with Gibson, came forward and delivered a powerful statement on what had happened to her. The Inquiry has granted Mary anonymity. At the 6th February 2018 hearing, the Chair decided he is going to release Gibson's real name to 'Mary' because she has the moral right to know. His real name, she got to hear in May 2018, was Richard Clark - he is deceased. More detail below.

- Eveline Lubbers, ‘Mary’ proves: sexual targeting was always part of spycops’ tactics, URG blog post, 30 January 2018.

- Rob Evans, Woman reveals police spy tricked her into relationship in 1970s, The Guardian, 31 January 2018.

- Eveline Lubbers, ‘Mary’ received the real name of #spycop ‘Rick Gibson’, URG blog post, 7 May 2018.

Update February 2020.

On 26 February 2020, the Undercover Policing Inquiry granted 'Mary's application to become a core participant in the Inquiry.[4]

Note from Undercover Research Group: if anyone recalls 'Rick Gibson' from his time in the Troops Out Movement or Big Flame, please get in touch. We appreciate that these events took place 45 years ago, and we also welcome corrections on how we have portrayed the history of the organisations mentioned.

Contents

Deployment as 'Rick Gibson'

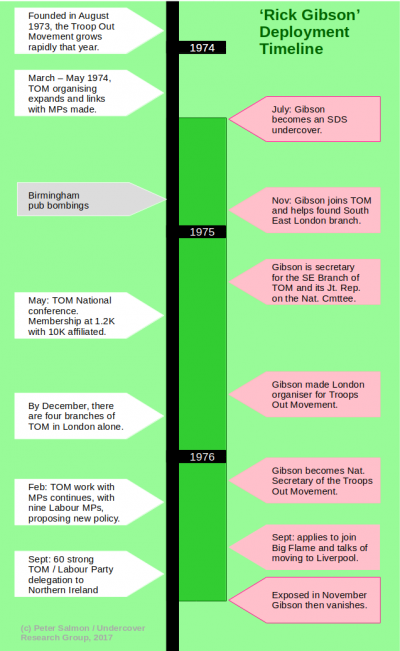

‘N297’ was deployed as an undercover from July 1974 to November 1976. In a Risk Assessment for him, the Metropolitan Police wrote: 'This was a shorter span in comparison to others [other undercovers], and cut short by compromise.'[3] As Gibson first turned up in November 1974 (see below), the first months of his deployment may have been the period in the back office of the SDS, learning the trade and exercising his cover story.[3]

Targets

Troops Out Movement - background

The Troops Out Movement (TOM) was a campaigning organisation set up in August 1973 a small group of anti-imperialist activists to counter the downturn of work on Northern Ireland by radical groups. In early 1972, after British Army paratroopers had shot dead thirteen protesters on ‘Bloody Sunday’, there were angry reactions across the world. Protests and marches included a 20,000-strong demonstration in London, organised by the Anti-Internment League (AIL). But by the middle of 1973, the same people were concentrating on the industrial struggles in Britain which were to bring about the three-day week, a miners’ strike and the end of the Heath Conservative government in early 1974.

As a new organisation, the TOM would be keyed into the increasing dissent about the aggressive use of British troops in Northern Ireland, and the concern about their mounting casualties. One of the founders was Alastair Renwick, who would become its Publication Coordinator and is now TOM’s historian and archivist, the author of numerous publications on TOM.[5]

- We adopted ‘Troops Out Now’, based on ‘Self-determination for the Irish People as a whole’ as our two demands. Unlike the Irish Civil Rights Solidarity Campaign (ICRSC) and the AIL, which had mainly shown the Irish face of protest, we wanted the TOM’s focus to be that of British people protesting about the use of their own troops in Ireland.

In his study of the TOM’s history, scholar Jacob Murphy shows how the TOM ‘played a fundamental role in shaping British parliamentary and extra-parliamentary responses to the Northern Ireland conflict’ in the 1970s.[6] It should not be forgotten, Murphy writes, that the normalisation of the relations between British parliamentary officials and Sinn Féin personnel in recent years and the peace process in the 1990s have started with TOM. He states:[6]

- TOM was the leading organisation in the British Left campaign for the withdrawal of troops from Northern Ireland. This was evident between May 1974 and December 1975 when the possibility of withdrawal was at its zenith.

‘British Left’ refers to parliamentary and extra-parliamentary organisations who worked with or within the TOM. Apart from Big Flame organisations working within the TOM included the International Marxist Group, International Socialists, Workers Fight and Revolutionary Communist Group. TOM also worked with the British labour movement, British Peace Committee, and British Withdrawal from Northern Ireland Campaign.[6] Although it was difficult, TOM managed to get MPs supporting their work. The most consistent ones, as Chessum remembers, were Joan Maynard and Tom Litterick. [7] In February 1976, they and seven other Labour MPs – Andrew Bennett, Sydney Bidwell, Maureen Colquhoun, Martin Flannery, Tom Litterick, Eddie Loyden, Joan Maynard, Ron Thomas and Stan Thorne – proposed and campaigned for a new policy on Ireland, including withdrawing the troops.[8]

Entry into TOM

Gibson appeared on the scene in the aftermath of the IRA’s Birmingham pub bombings in November 1974. He wrote to the national office of the Troops Out Movement asking if there was a branch in south-east London that he could join. The letter was very well timed. The TOM was a fast growing organisation gaining influence, as was described above. Richard Chessum, a student politically active in the Students Union at Goldsmiths College, remembers that he was already looking for students who would be willing to help set up a new South East London branch. Chessum:[9]

- The new interest in the Irish situation was confirmed by Rick’s letter. There was the additional factor that, in the aftermath of the atrocities that were the Birmingham pub bombings, we knew of Irish people suffering verbal and sometimes physical assaults in the streets. Today, they would be called hate crimes. We believed that the British government policy of the time was counter productive and making the situation worse.

He had previously been involved in campaigning on Northern Ireland, in the Anti Internment League. He had been one of the main organisers of a march to Woolwich Barracks protesting against internment without trial and had been the person negotiating the route with the police. In hindsight, Chessum thinks his high profile may have made him of interest to the SDS.

Big Flame - background

'Big Flame was a Revolutionary Socialist Feminist organisation with a working-class orientation in England. Founded in Liverpool in 1970, the group initially grew rapidly in the then prevailing climate on the left with branches appearing in a number of cities.'[10]

For Big Flame, Northern Ireland was one of the main issues they were involved in. In one of the first pamphlets the group produced in 1975, Big Flame's set out their position: 'We oppose British involvement in Northern Ireland, and support the republican and revolutionary demands for troops out now, for self determination for Irish people as a whole, and for a united socialist Ireland'. In the years that followed motions on Ireland at Big Flame Conferences often contained the slogans of the Troops Out Movement: 'Troops Out Now' and 'Self Determination for the Irish People as a Whole'. The 1975 pamphlet Rising in the North was based on the analysis that: 'the origin of the situation in the north of Ireland was traced back to British imperialism and the partition of the country. The introduction of British troops was seen not as a move to keep the peace, but to contain Catholic rebellion.'

They published a monthly newspaper, also entitled Big Flame, and a journal, Revolutionary Socialism. Distinctively, Big Flame members intervened both in waged workplaces (most famously in Fords), in neighbourhoods (on housing issues, play facilities etc), in the social movements (especially among women, anti-racists and on Ireland) and they developed their personal politics. They critiquing both Trotskyism and Leninism, in time, they came to describe their politics as 'libertarian Marxist'. The organisation was wound up in about 1984.[10][11]

Entry into BF

Once he had established his position within the TOM, Gibson became a part of the loose network of left-wing groups in London - and this is also how he got involved with Big Flame. As Chessum explained:

- There were many of us at the time who were former members of different Marxist groups and had left them for one reason or another, usually because of the dogmatism or authoritarian ways of organising. We nevertheless agreed with much of their analysis of capitalism and felt the need to meet together regularly to carry on discussing issues in a rather freer and more informal manner. [...] Some of us were attracted by a non-Trotskyist far left organisation called Big Flame which seemed more libertarian and open-minded than the orthodox groups, and I began going along to their discussion groups. When Rick discovered this, he asked if he could come along. This he did.[1]

Cover story

Personality

As far as Chessum can remember there was nothing extraordinary about Gibson’s appearance. He was quite tall, slim and bearded, always with a relaxed expression on his face. He never saw him angry; the person he portrayed himself as being was kind, considerate and social:

- Quite laid back. Not ever responding emotionally to things. Exhibiting a sense of humour. Laughing when we joked about the sectarianism in the organisation. Never actually criticising anyone himself. Just reporting to me factually how others in the organisation were behaving. He could, of course, have misinformed me about some things, but I never caught him out doing so. I suspect being factual and accurate was one way of getting himself trusted. Things he told me would be confirmed by others when I saw them.

Chessum considered Gibson a friend and spent quite some time with him, including socially. They used to watch Charlton Athletic occasionally and spent their lunch time together when they both worked in the same area. They did not talk about private things, such as his background. Chessum: ‘I do not remember ever asking him about it. I wonder what alibis he would have had ready constructed if I had.’ [7]

Residence

When he first contacted TOM, Gibson gave an address in Putney, in south west London. Investigating Gibson's background, Big Flame did not manage to find anyone in the South East London groups who had been to his Putney flat. After the undercover had disappeared, Richard Chessum spoke to one of Gibson's female friends who had been there on one occasion. 'She was convinced that it was not lived in and that he was really living somewhere else.'[1]

Over time, Gibson hinted at moving in with Richard Chessum who shared a flat with his partner and a couple of other political activists in Burrage Road, SE18.[12] Chessum: 'One of the other activists who lived there was a man who made frequent trips to Belfast and actually wrote under a pseudonym (Peter Dowling) for the Republican newspaper, An Phoblacht (Republican News)'.[9]

And just before he was found out, Gibson claimed he had moved to south east London, giving an address there (possibly Peckham). The day after the final confrontation, Big Flame went to pay him a visit at his new address, but discovered only an unoccupied flat, without a stick of furniture.[1]

Vehicle

Rick Gibson had a car at a time when the rest of the London South East branch was reliant on public transport. One of his first tasks as the new secretary of the Branch was to drive Richard Chessum round to the houses of people who had been active earlier in the Anti-Internment League to see if they would like to get active again.[1]

Chessum remembers an occasion when Gibson drove him around to visit local labour movement people to sponsor something TOM was doing. 'The Chair of Greenwich Trades Council was always a good bet and very friendly, so we went to see him. As we approached his house, his car was just driving away with his whole family inside'. Rick decided to try and catch him at the next traffic lights to avoid having to visit him again.' What evolved was a chase, jumping red lights, all the way from Blackheath to Erith - about ten miles. Chessum’s 2002 memory of the incident:[1]

- 'I'm not going to lose him now' Gibson said. I implored 'Rick, you can't do this, it's like a police chase.'

- At the end of the journey, I refused to leave the car, not wishing to jeopardize a long acquaintance with our local sponsor. Rick had no such inhibition, walking up to him with some purpose. The Trades Council Chair had realised he was being followed and looked quite shaken by the experience. Fortunately, he did not see me. But I'm sure he was intimidated by Rick. What was the purpose of this exercise?

Occupation and office

In the summer of 1976, Rick claimed he had started work as a van driver for a firm in Woolwich. Richard Chessum also happened to work in Woolwich, he had a temporary job with the London Electricity Board whilst waiting to apply for a grant for a Ph.D from 1976, and Gibson suggested they would meet at lunch time for a chat: ‘sometimes in a local pub and sometimes, at my suggestion, travelling across the Thames and back on the Woolwich Free Ferry, which was a nice way of spending the lunch hour.’[7] Chessum recalled that this so called firm ‘was in the same premises as a bank, but at the back of the building, up a wooden spiral staircase. On the top floor was an office door, and inside an office with lots of files, a receptionist, and Rick. It was completely cut off from all the other people using the building.' [1]

After Gibson was confronted and disappeared, Chessum went to check, but employees of the bank in the same building told him the firm had moved only a month or so before and was now based in Maidstone. When he called the number he was given and asked if Gibson worked there, they said they would find out, to come back saying Rick was out at the moment but could he leave his name and details.[13]

The Big Flame investigation of Gibson (see below) discovered the company was registered as a subsidiary of Dart International, a US transport company that still exists (it appears as Dart Entities.[14] It is not known, if the name of the company was used as a front, or whether the company actually lent its name to the SDS.

Relationships

'Rick Gibson' has been in four relationships that we know of.

The first short-term ones were with two women Richard knew, one active in the Socialist Society at Goldsmith and in solidarity work, the other in the Troops Out Movement South East London Branch. The women were friends sharing a flat, and students at Goldsmiths College. After Chessum found out that Gibson had disappeared, he visited them. Without having heard of the investigation, they told him they had figured out between them that Gibson had to be a policeman. They had no evidence, but had decided this the only explanation for his behaviour - always leaving before the morning, never visiting at weekends - which suggested he was going home to a wife and family.[1]

One of the flatmates came forward in January 2018, a few weeks after this profile was first published late November. She submitted a powerful statement on what had happened to her to the Undercover Policing Inquiry; she was granted anonymity and uses the name 'Mary' (see below). She was politically active in the student movement and a member of the Socialist Society. The first time she met Gibson was at Goldsmith College when he approached her while she was distributing political literature. He came up to her and showed an interest in their political campaign. He pretended to be new, and 'Mary' thought it was she who had introduced Gibson to her friends in the TOM in late 1974, early 1975.[15] Rick Gibson very quickly became a frequent visitor to the flat to see Mary and her flatmate to coordinate TOM publicity and planning - as well as for socialising and conversation. 'Mary' in her statement:

- At one point while he was still a regular visitor, Rick Gibson and I became sexually intimate for a short period of time. It was a rather half-hearted effort from his side, he came across as sexually dysfunctional.'

After he moved up in the Troops Out Movement his interest in the student scene faded, and Mary never heard from him again, they didn’t keep in touch.[16]

Later in his deployment, the undercover officer had relationships with two other women, both of whom were active in Big Flame and in the TOM. One was someone living in west London at the time,[17] and the other south London - she sadly passed away in the mid1990s.

Coincidently, confirmation for the last relationship was discovered in a book by Michele Roberts, a partly fictionalised autobiography called Paper Houses. Remembering her time in a shared house in Talfourd Road in south London Roberts describes the people she lived with, one of them a woman whose boyfriend turned out to be a spy:[18]

- I remember Dina, who lived with us for a while and who was a member of the small libertarian group Big Flame, making us breakfast to hearten us one chilly morning before a Troops out of Ireland demonstration: scrambled eggs thick with bran. Who needed body armour for protection against truncheon blows? We were fortified by character armour: breastplates of bran.

- Dina’s lover, we discovered later, an amiable chap who ambled about after her like a devoted spaniel, was in fact a Special Branch spy, set on to her to infiltrate the revolutionary group and act as an informer. Less a pet than a bloodhound; a sniffer dog. Served him right that in order to spy effectively he had to endure Dina’s breakfast special. The Full Trotskyist.

Roberts mentions attending a Troops Out demonstration in February 1976 which was attacked by the National Front. Later on the same page she says that Dina had moved in by that time: 'very idealistic (hence her membership of the far-left Big Flame), very gentle, very keen on wholefoods (and bran in her scrambled eggs), joined me in gardening. We produced splendid crops of marrows, potatoes, tomatoes, runner beans and lettuces.'[19]

The author has confirmed that ‘Dina’ was indeed a pseudonym for the woman who has died. 'We shared the house but I didn't know her well at all, as she went to Big Flame meetings and activities and I went to feminist ones. I remember her as a very gentle, kind person.'[20][21]

Richard Chessum had told us about Rick's amusement when they were not given an address by Big Flame, but just told to 'meet at Dina's'[12] - he now wonders whether this was the house mentioned in the book. 'Certainly there were a number of other feminist women there who joined in the discussion - I had always assumed they were in Big Flame, but of course several of them could have been women who lived there and were invited to participate just like Rick and myself.[22]

When Gibson disappeared, as explained below, he wrote a farewell letter to the woman he was seeing at that point in time, August/September 1976. In it, Gibson denied he was a police spy, claiming he was on the run from the police. Richard Chessum has seen this letter, and he is sure it was not addressed to any of the four women mentioned here. Whether this means there was a fifth relationship, or that the letter was redacted remains unclear.[12][23][24]

Friendships

Gibson befriended Richard Chessum, and was involved in the same political activities. A political activist in the 1970’s Chessum played a leading role in the Troops Out Movement (TOM). For a time he was also close to, but not a member of, a Big Flame. Chessum background may have put him in the spotlight, and a target for Gibson:

- At the time I was a student politically active in Goldsmiths. I had in fact been a candidate for President of the Students Union. I had also been involved in a previous organisation campaigning on Northern Ireland, the Anti Internment League. In this latter capacity I had been one of the main organisers of a march to Woolwich Barracks protesting against internment without trial and had been the person negotiating the route with the police. I therefore had a high profile, which I think may have made me of interest to the SDS.[25]

Career as undercover

Roles in TOM

Gibson did not have strong political views, rather he played a different part. TOM being an organisation with a lot of discussions and conflicts between different groups, there was a premium on trying to hold the group together. Quietly getting on with the routine work of the organisation, Rick managed not to offend anyone - which turned out to be a major asset, according to Richard Chessum. This made it easy for him to climb the ladder within the organisation, as is shown by the roles he fulfilled (listed below).[1]

By the end of 1974 there were four TOM branches in London, in west, east, north and south London. The number would continue to grow over the next year or so with new branches appearing in north and the new South East London branch formed by amongst others Richard Chessum and Rick Gibson. Subsequently - a central London branch was also set up. John Lloyd, who was active at the time in both the West London branch and the North London one, explains:[26]

- There was a members meeting in 1974 in which the constitution and structure of TOM was adopted. It was to have a central steering committee in London and affiliated local groups. Officers were to be elected to the steering committee at the AGM and policy was also decided there. There were local branches set up and active before this meeting.

Chessum explains the situation in more detail: [27]

- There was a miscellaneous group of us who were independent from the many Trotskyist groups. It was easy for Rick to attach himself to us, both in the local branch and nationally. This would have been the most useful for him as we were basically running the TOM, along with Big Flame.[28] Big Flame were the only organised group in alliance with us, though we could rely on members of the International Marxist Group (IMG) siding with us against the smaller sectarian groups who wanted to increase their influence (by which I mean the Revolutionary Communist Group RCG and Workers Fight).

So, remaining on friendly terms with everyone, but also attaching himself to the then controlling group within the TOM and volunteering to undertake work on their behalf helped Gibson to make his way up to the top echelons in less than two years (exact dates to be ascertained[29]):

- 1975: Secretary of the South East London branch of TOM. Rick volunteered for this role at an opportune moment, as according to Chessum, 'most active of us were coming up to final degree exams'.[1]

- Along with Richard Chessum was joint Representative of the TOM South East Branch on the National Committee.

- London organiser for TOM.

- 1976: National Secretary of TOM (one of the two). In this role, he had possession of the names and addresses of all members across the country.[1]

Scheming

In hindsight, Rick also made good use of the information he gathered through talking to his friends within TOM and BF, and of the never-ending scheming between the different factions aiming to dominate the various campaigns they were involved in. Chessum:

- Most of our local meetings were in Charlton House, and we usually adjourned to a pub afterwards to discuss political developments on Northern Ireland. Rick was almost always there. There were problems with sectarian divisions in TOM, mainly fostered by organised small left groups, and Rick and I, along with one or two other independents, would often be involved in discussion about these internal matters.[9]

‘Political organisations of the left would decide whether to support campaigning groups like TOM. If they chose to do so, then they would make sure some of their members were inside it and working for it. Alan Hayling was one of the Big Flame people active in TOM.’ In the same vein, when TOM needed a London Organiser, people got together to discuss who it should be. Chessum: ‘It was important who it would be, preferably someone who was acceptable to everyone, but definitely from our point of view not someone in one of the more sectarian left groups.’ Feelers were put out to different people. Chessum was approached by Alan Hayling, while at the same time the wife of his good friend Renwick, Liz Curtis was sounded out from within TOM – which would put the two of them in competition. Chessum: ‘Not long afterwards Alan told me to forget about it because a decision had been taken to accept an offer from Rick to do it.’ [27]

Recalling discussing the internal scheming and the personal flaws of some of the key members with Gibson, Chessum says: ‘Rick may at this point have seen this as his great chance to become London Organiser himself. I wonder how much the fact that Rick had been friendly with me was a factor in him being trusted enough to be appointed.’[27]

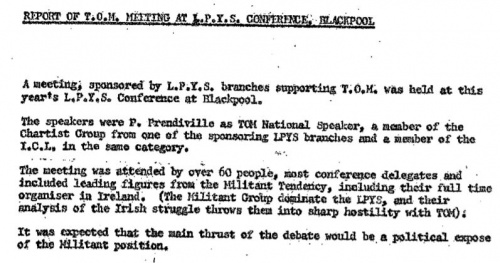

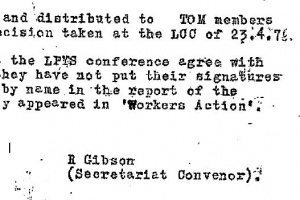

Another example of Gibson’s role in the conflicts between different factions at the time is captured in a document authored by Gibson which was discovered in Alastair Renwick’s archives. It is the report of a meeting at the Labour Party Young Socialists' Conference in 1976[30] that was set up to discuss the differences in views between the TOM and the LPYS, dominated at the time by the Militant group. The meeting ended in a shouting match, or to quote Gibson's summary: 'a tirade of vicious, sectarian abuse.' According to Chessum the report was written in a sophisticated way, and aimed at supporting the faction that Gibson had attached himself to. Chessum doubts that Gibson had the abilities to draft it by himself, and thinks he must have had help from TOM staff.[31]

Suspicions

When Gibson wrote to the TOM asking for a branch in south east London while he did not live there, this was thought of as strange but accepted as he said he had signed on as an evening student at Goldsmiths, allegedly to learn Portuguese.[1] It is not known if he ever went to any of the courses, but Richard Chessum remembers that Alan Hayling, a key figure in Big Flame, was working on a film documenting the 1974 uprising in Portugal then taking place.[12] The choice for Portuguese may have been part of a premeditated plan to get closer to Hayling in due course.

Prior to joining TOM, Rick seemed to have no political past and no Irish connections. Normally those who became active on the Northern Ireland issue were people who had been active on other things and then applied the insights they gained to Irish politics. From campaigning on Vietnam or South Africa, the focus on Ireland was a natural progression for many. For others their activity came from having Irish connections or ancestry. With Rick, neither of these things was the case.[1]

Richard Chessum never had many suspicions of Rick during the course of his deployment, but for a weird feeling at the beginning that soon evaporated: [1]

- Ironically, when we first met Rick, my girlfriend and I had discussed with each other very seriously whether he could be a state agent. He had no political past, he really did not seem to know much about Ireland. Why was he with us? [...] Later, however, when we had known Rick for a year or two, we laughed at ourselves and felt quite abashed that we had been so paranoid as to have had the aforesaid conversation.

It was only in retrospect that conversations and incidents took on new significance.

At the first public meeting to launch the new branch, a woman from west London TOM who had recently visited Northern Ireland and met with community activists there, brought some slides which she had taken on her visit, and this was followed by general discussion. Chessum: 'On her way back to west London that night, unknown to us, she was apprehended, taken to a police station, and the slides confiscated. It was a day or two later before we heard about it from people in West London TOM. The incident greatly surprised them and us, and Rick affected to be surprised too when we discussed it with him.'[9]

Chessum also remembers a discussion with Rick in the pub, about who could be a state spy in TOM:[1] ‘What on earth would they think of us? Perhaps when they saw the infighting, they might decide they were superfluous. On the other hand, we were really not the kind of awful monsters they would have been led to expect when they were assigned to the work.’ And when Chessum told Gibson he was surprised that his [Chessum’s] flat had never been raided under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (as others had been), the undercover asked him why he thought that was: 'I told him the only reason must be that they had very good intelligence on me anyway. Rick said this was an interesting theory and agreed it could well be true.'[1]

According to Chessum, people who had been active in the Anti-Internment League (as mentioned above) - almost all Irish - eyed Rick 'with great suspicion, not knowing who he was, though I did introduce him as the new secretary of our Branch.[1]

Big Flame were indeed suspicious of Gibson for various reasons. At the Big Flame discussion groups held at the flat of a member in south London, the attendees took turns to introduce a discussion on a particular topic. Chessum: 'When it was Rick's turn, he made a complete hash of it, and there was general embarrassment all round, though people very kindly tried hard not to show it.'[1] When Gibson said that he was possibly going to live in Liverpool this raised another red flag, because that is where Big Flame had one of their biggest branches with most contacts to Ireland because of its geographical location. Alan Hayling told Chessum this included close connections with Republicans in the nationalist communities in the north of Ireland and making many visits to them. [7]

Investigation, confrontation and exit

In September 1976, Rick Gibson indicated he wanted to do more than just visit Big Flame meetings which were open to anyone interested, and applied for membership. This required a more formal procedure with the greater access to the inner workings of the organisation that it accorded.

Big Flame carried out 'security checks' on people who puzzled them.[1] They told Rick they ran a routine check on everybody who applied to join and asked him to prove who he was by providing details of his family and his schooling. Nothing checked out. The school he claimed to have attended had no record of him; someone travelled all the way to the northeast of England to check a Gibson living there - she said she had never heard of him.[12] Rick also told them he had worked on a caravan site near outside Harwich[14] before coming to London, which turned out to be run by an Army major and his son. When confronted with these inconsistencies, Rick tried to bluff himself out. He said he had been expelled from school and had been ashamed to tell them. The relative must have moved.[1]

What Rick did not know was that Big Flame had by then made a more significant discovery. Having obtained his apparent date of birth they checked the registry then held at Somerset House. They indeed found the birth of a Richard Gibson recorded to have taken place in the right year, which seemed to confirm the identity of the person known as Rick. They wanted to be sure and went to look up the local records in a certain town somewhere in the UK.[32] 'There they found his birth certificate again and, on turning the page, his death certificate recording his demise' - not much later.[1]

Confrontation and exit

Big Flame were now sure he was a not who he said he was and clearly an undercover person of some kind; they speculated that he might be police special branch, military intelligence, or even a fascist.[9] They wanted him out of their group and the Troops Out Movement.

Alan Hayling told Chessum that they asked him lots of personal and intimidating (they hoped) questions, hoping to frighten him away. To stop him from bluffing his way through, they took him to a pub and waited for his turn to buy a round. When he returned with the drinks, the birth and death certificate were on the table. Chessum was told 'Gibson trembled and went white as a sheet. He seemed emotional and close to tears.' Even then he claimed it was a mistake in the records office and gave them a number of his brother - which was yet another dead end. The next morning they found out his new house was empty. He was never seen again.

Gibson wrote a letter to one of the women he had had a relationship with, which Chessum has seen:

- Rick stated that he was very sorry not to be seeing her again. He denied being a spy, stating that he had once committed a serious criminal offense and had been on the run ever since, necessitating a complete change of identity.[1]

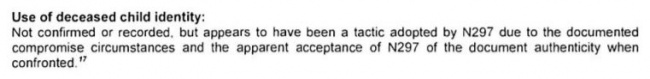

The same exit-story now appears in the risk-assessment the Metropolitan Police submitted for 'Gibson' - that he used to identity of a deceased child to avoid detection and arrest. 'He left Big Flame stating that if activists could find him so could the police. He was withdrawn as an SDS UCO; the SDS management having confidence his true identity was intact.' (The reference given for this information has been redacted.)[3] The police found a further reference to the confrontation. The author is redacted: ‘In 1976 an officer (N297), targeted against the Trotskyist organisation Big Flame, was confronted with the death certificate for his covert identity by fellow members of the group. No violence was used and he was expelled from the group after a lengthy tirade of abuse.’[3]

N.B. Big Flame were not Trotskyist, they were quite hostile to Trotskyism as well as Stalinism.

(non)-exposure

Big Flame decided not to go public with their findings. Aly Renwick says that the TOM had realised early on that if their work succeeded in putting pressure on the government of the day then they would inevitably come under the scrutiny of the state intelligence services. Renwick: ‘To succumb to paranoia over the issue of state agents would have been totally counterproductive and indeed would probably have aided the establishment to paralyze our work’.[33]

The group opted for a low-key approach, telling people only on a 'need to know' basis. While they were investigating Gibson, they had taken pictures of him on demonstrations to be able to warn people who should know. Separately from that, the whole investigation was recorded and given to one or two people in sealed envelopes, who were asked not to open them unless something happened to anyone in Big Flame involved in uncovering the story.[1] Someone close to the investigation remembers it slightly differently and says the envelope containing his details was primarily intended to be given to the National Council for Civil Liberties, before Gibson was confronted, as people had no idea if there would be repercussions from the police.[14]

Media mentions

The Metropolitan Police’s Risk Assessment lists three ‘Compromises / potential compromises subsequent to UC posting’, in other words moments when there was a risk that Gibson could have been mentioned in the media:

- 1986: The MPS has a record of Mike Hollingsworth and Nick Davies then investigating the work of the SDS for the Observer, attempting to discover more about a man named 'Gibson' who had been involved with Big Flame and trying to get more details as well as photos.[3] Chessum indeed remembers that Mark (not ‘Mike’) Hollingsworth came to talk about Gibson, but nothing came of it.[7]

- 1989: Geoffrey Seed, Channel 4 producer, wrote to the police to obtain the photograph of 'Gibson' that he knew to have been distributed by Big Flame.[3]

- 2013: ‘In the book 'Undercover' there is a reference by ‘Peter Black’ (N43) that an SDS officer in the 1970s was confronted by his target group with his birth and death certificate. There is no specific mention of N297 in his true identity or his pseudonym but the incident is similar to the one he endured.’

The last item refers to a fragment in the book by Rob Evans and Paul Lewis, where the authors quote whistle-blower Peter Francis (then still known as Peter Black). The context is fear of being found out and Francis explains how, when he was still undercover in the 1990s, at a party an activist tells him the story of an undercover officer who was found out and confronted.[34] Francis at the time had also heard a version of the same story from colleagues in the Special Demonstration Squad, when it was told as a cautionary tale of the dangers of being undercover.[35]

However, not cited in the MPS Risk Assessment are two other investigations that indeed did lead to publication a long time before the undercover policing scandal broke in 2011:

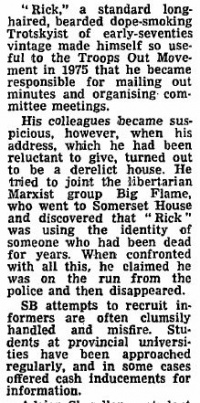

- 1984: Nick Davies and Ian Black published a series of articles in The Guardian - the second day focused on how intelligence was gathered. One section, Infiltrating agents of counter-subversion spoke of Gibson in particular (see picture).[36]

- 2002: True Spies, the 2002 BBC three-part series on the work of the SDS. It was produced by Peter Taylor who had secured the full support of the Metropolitan Police after speaking to its Commissioner. Then the head of Special Branch Roger Pearce encouraged SDS officers to talk to Taylor and to watch the series.

True Spies

In True Spies, one of the undercover officers interviewed by Peter Taylor talks about infiltrating the Troops Out Movement. Richard Chessum, Alastair Renwick and John Lloyd are all sure that this man given the pseudonym 'Brian' is the same person they knew as Rick Gibson.

In the first episode of True Spies, 'Brian' explained how he took part in debates and chaired meetings. He recalled how difficult it was to become an expert on dialectical materialism, to learn the language and the ideology:[37] Brian: I wouldn't say I became a revolutionary - but certainly, there were times when I became very close to being native...

However, it is what ‘Brian’ said about friendship that convinced Richard Chessum:[38]

- They would probably feel that I abused the friendship. The fact of the matter is it was a friendship which I valued at the time, and I enjoyed, but the objective was to provide a service.

Richard remembers how he discussed a very similar issue with Rick back in the days:[39]

- I once chatted to him about the likelihood of our organisation being infiltrated and surmised that the intelligence services would have a view of us as very sinister people. What, I asked, would an infiltrator make of us when he actually met us? Rick smiled and said 'Perhaps he would like you'.

Screen shots of 'Brian' taken from True Spies, 2002.

As more than 25 years had passed since Richard had last seen the person he had known as Rick and 'Brian's' face was partly covered in True Spies, Chessum approached the BBC for confirmation and to ask if he could meet his former friend again. He wrote a long letter to Taylor with detailed memories of Gibson and the investigation into the suspicions (the six-page letter is used to compile the first draft of this profile).[1] It was months before Taylor answered (he claimed the letter never reached him the first time) and only to deny that the officer called ‘Brian’ in the series was Rick Gibson. He also wrote: '[W]hat you describe bears no relation to what I understand to be the experience of any of the undercover Special Branch officers I interviewed or met in the making of True Spies’.[40]

With everything that has come out since the spycops scandal broke in 2011, we know that most of the undercover officers indeed built friendships (including deceiving women into relationships) and were often deeply trusted by their comrades.

In April 2018, the Inquiry revealed that it had not been Gibson, but the undercover officer known as HN302 who appeared in the True Spies documentary under the pseudonym 'Brian'.[41]

- For more detail on what the undercover officer said in True Spies, see the profile of HN302.

- The first episode of ‘’True Spies’’ can be watched here: Subversive, my ass, (Brian appears at 14:00 min, then again a few times starting from 16:10); also see the full transcripts.

- For more on Peter Taylor's close cooperation with the MPS, its commissioner and Special Branch, including their correspondence, see The True Spies Story at the Special Branch Files Project website, which also includes links to the other episodes and their transcripts.

Undercover Policing Public Inquiry

'Rick ' is referenced by the nominal/cypher HN297 for the purposes of the UCPI. On 3rd August 2017, his cover name was released by the Inquiry, along with details of dates and targets of his deployment.[2] As such he is also one of the first SDS / NPOIU undercover officers to be formally confirmed by the Inquiry who had not been previously exposed by activists in public. (However, 'Gibson' was found out by his comrades and confronted back in the days as explained above.)

The Risk Assessment made to advise the Inquiry about his anonymity application seems to imply that not much about his mission was recorded. There is no file on his recruitment, nor on his use of the identity of a dead child:[3]

The Metropolitan Police have applied to have his real name restricted by the Inquiry,[42] although the redacted Risk Assessment states 'threat considerations' are 'not applicable as N297 is deceased'.[3] The Chair, John Mitting, has indicated he is ‘minded to’ grant the application,[43] because the publication of his real name would 'be likely to interfere with the right of his widow'.[3]

- 'As in the case of the living officers cited above it is unlikely that the publication of his real name would prompt the giving or production of evidence necessary to permit the Inquiry to fulfil its terms of reference. It would be likely to interfere with the right of his widow.'

At the November 2017 hearing of the Undercover Policing Inquiry, the Undercover Research Group revealed that Gibson had been in at least two, but maybe four relationships with women. It was clear that the Inquiry nor the police knew anything about this. Mitting agreed that this ‘puts a very different complexion on matters.’ He was quick to realise the importance of the revelation, since Gibson’s deployment was so early in the life of the SDS’s activities. Referring to Gibson by his code-number, Mitting added:[44]

- HN297 is 1974 to 1976, that is probably in the period when practices started to be adopted routinely and things may have started to go wrong'.

Regarding the forming deceitful relationships he also said, 'whether this is individual officers going off-piste or whether it is actually a practice is one of the things I have to try to get to the bottom of.'[45]

Disclosure of Rick Gibson's real name

In fact there are enough reasons to release Gibson's real name, even within the Inquiry's set of rules:

- Mitting says he feels a 'moral obligation' to disclose real names to women deceived into relationships, including specifically in this case.[46] In his statement, Richard Chessum testifies that he has spoken to two of the women Gibson had been involved with.[9]

- The risk of infringing the right of privacy (art 8 European Court of Human Rights) of the widow turned out to be a misleading if not fraudulent claim. At the hearing it became clear that the Inquiry had never spoken to the widow of HN297; Mitting admitted he had no statement from her on file.[45] It is important to note that the Chair had accepted the claim in the Metropolitan Police's Risk Assessment that the publication of his real name would 'be likely to interfere with the right of his widow'[3] without any further checking.

- Mitting tends to disclose the real names of officers who, after their deployment as an undercover, took on a managerial role with the SDS. The Risk Assessment states that 'N297 returned to the SDS later in his career in a non-undercover role.'[3] However, at the hearing the Counsel for the Metropolitan Police mr Hall QC claimed that they had still not worked out whether Gibson had been a manager: 'Our current view is that he was not a manager, although there are indications the other way.'[45]

- In the context of wanting to go to the bottom of when things started to go wrong, as mentioned above, Mitting suggested that 'the public interest in publishing becomes much more compelling.'[45]

However, after the hearing Mitting decided 'to wait for further information on HN297 from the non-state core participants' - from those spied upon.[47] This means that instead of releasing the real name to allow others to come forward, such as possible former colleagues who might know more about Gibson's career, indications that something 'went wrong' are not enough for the Inquiry to take action. And despite the 'moral obligation' to deceived women, the latter first need to come forward to ask for disclosure in person. (By implication, this means that indirect evidence - in this case that of Richard Chessum who had spoken to two of the women - is not enough for Mitting.) And the Inquiry does not actively look for women deceived by undercovers until now.

In January 2018, Mary, one of the women who had been in a relationship with Gibson, came forward and delivered a powerful statement on what had happened to her. The Inquiry has granted Mary anonymity, and at the 5th February 2018 hearing, the Chair decided he is going to release Gibson's real name to 'Mary' because she has the moral right to know. He also said that in not granting an anonymity order it does not 'automatically follow that the Inquiry will publish the real name'. Rather, it means that if there is no restriction order their names will not be redacted if and when documents will be released in the evidence phase of the Inquiry.[48] The MPS were given until February 15 to make a submission for the family of the undercover officer, though Mitting made it clear that he is not minded to change his mind on releasing the name.[49]

On 20 February 2018, the Inquiry Chair stated:[50]

- I refuse to make a restriction order in respect of the real name unless, HN297 by 4pm on Thursday 8 March 2018, the Inquiry receives evidence which casts serious doubt on the evidence contained in the witness statement of 'Mary'.

The Inquiry has subsequently said that 'no evidence casting doubt on 'Mary's witness statement was received' so the Chair did not review his decision. Gibson's real name has been released to 'Mary',[51] just to her, which was reported and critisized in this Undercover Research Group blogpost in May 2018. Also in the blog is 'Mary' response to the Inquiry, questioning why it was send to her personally, and why the burden was put on her to decide whether to publish it or not.

Issues relating to the application for anonymity of Rick Gibson's real name were also addressed in: the NPSCP submissions by Phillippa Kaufmann, QC & Ruth Brander of 5 October 2017[52]; Witness Statement of Tamsin Allen, 18 December 2018.[53]; MPS submissions of 5 February 2018.[54]

For more detail see: Eveline Lubbers, ‘Mary’ proves: sexual targeting was always part of spycops’ tactics, URG blogpost, 30 January 2018; and ‘Mary’ received the real name of #spycop ‘Rick Gibson’, 7 May 2018.

In February 2020, 'Mary' was granted core participancy in the Inquiry.[4]

Police line of command

Robert Mark, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police (1972-1977.[55]

- Colin Woods 1972-1975 & John Spark "Jock" Wilson 1975-1977, Assistant Commissioner "C" (Crime), head of CID Woods was appointed Deputy Commissioner in 1975 and was succeeded in his position by Wilson, who had been his Deputy Assistant Commissioner since 1972.[56]

- Victor Gilbert, Commander of Special Branch 1972 - 1977, with rank of Deputy Assistant Commissioner.[57]

- unknown, Head of S Branch' (Detective Superintendent rank)

- unknown, Head of the Special Demonstration Squad (Detective Chief Inspector rank)

Notes

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 Richard Chessum letter to Peter Taylor, BBC, 21 November 2002.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Press Release: ‘Minded to’ note, ruling and directions in respect of anonymity applications relating to former officers of the Special Demonstration Squad, Undercover Policing Public Inquiry (UCPI.org.uk), 3 August 2017 (accessed 3 August 2017).

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Graham Walker, N297 Open Risk Assessment, Metropolitan Police Service (via UCPI.org.uk), 31 May 2017 (accessed 29 August 2017).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sir John Mitting, Core Participants Ruling 34 / Recognised Legal Representatives Ruling 28 / Costs of legal Representation Awards Ruling 27, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 26 February 2020.

- ↑ See for instance: Aly Renwick, Oliver’s Army. A history of British soldiers in Ireland and other colonial conflicts (2004); and Alastair Renwick, Something in the air: the rise of the Troops Out Movement, in Graham Dawson, Jo Dover, Stephen Hopkins (eds), The Northern Ireland Troubles in Britain: Impacts, engagements, legacies and memories, Manchester University Press, 2016.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Jacob Murphy, Troops Out Movement, 1973-1977, Introduction, 24 June 2015 (accessed October 2017)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Email from Richard Chessum, 22 October 2017

- ↑ The MPs stated that: ‘What the Government has done, and continues to do, is to underwrite the perpetuation of the Northern Ireland state as it was set up in 1921’ and that this ‘offers no solution’. They then proposed an alternative policy: ‘First: Northern Ireland must again be placed in an all-Irish context ... Constitutional changes have to begin to be made, which involve the people of Ireland, and of Britain. Unionists can no longer have exclusive rights in deciding the future of Ulster. Second: There must be a clear declaration by Britain that it aims to with draw from Ireland, politically and militarily, within a limited period of time ... negotiations and actions must go side by side ... These are the fundamentals of a new policy on Ireland.... The government of Britain has positive instruments to hand if it will only use them. The ultimate solution, as it has been with other nations divided by a colonising power, lies with the people themselves. But for us the only solution lies in going to the root of the problem, which is here in Britain: in our unwillingness to actually get out!’ (The British Peace Committee produced the full statement as a leaflet 17 February 1976). Source: Renwick, Something in the air: the rise of the Troops Out Movement (2016)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Richard Chessum, Draft application for Core Participancy in the Undercover Policing Inquiry, November 2017

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Big Flame created a website in 2009 after a reunion held 25 years after the group dissolved. In a pub on the Grays Inn Road, '15 ex-member came together, reminisced and discussed the very positive role the organisation played in the politics of the 70s and 80s.' Big Flame, Who we were, Big Flame website, 2009 - also see the many comments at the home page and this page, commenting the self-description (accessed September 2017)

- ↑ The name Big Flame came from a television play by the same name, written by Jim Allen and directed by Ken Loach for the 1969 BBC Wednesday Play season. It dealt with a fictional strike in the Liverpool Docks.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Interview with Richard Chessum in Sheffield, 30 September 2017

- ↑ When Chessum first rang the number it was engaged. After he put the receiver down, it rang him back, but when he picked up the phone there was no-one there. Only the third time he got through. Richard Chessum letter to Peter Taylor, BBC, 21 November 2002.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Email from Big Flame people involved in the investigation in 1976, early October 2017

- ↑ Undercover Research group interview with 'Mary', 18 January 2018

- ↑ 'Mary', Statement to the Undercover Policing Inquiry from ‘Mary’, 25 January 2018 (accessed February 2018

- ↑ The Undercover Research Group has only communicated with her by an intermediate; she has made it clear that she does not want to come forward

- ↑ Michele Roberts, Paper Houses: A Memoir of the 70s and Beyond, Virago, 2007, p123. Thanks to Carolyn Quertango for pointing this out.

- ↑ Michele Roberts, Paper Houses: A Memoir of the 70s and Beyond, Virago, 2007, p146

- ↑ Michele Roberts, email to the Undercover Research Group, 25 January 2018

- ↑ The Undercover Research Group knows the real name of 'Dina' but has decided to respect her privacy by not publishing it.

- ↑ Richard Chessum, email to the Undercover Research Group, 27 January 2018

- ↑ Richard Chessum, email to the Undercover Research Group in response to the Michelle Roberts discovery, adding that Big Flame did consider themselves not as Trotskyist, as Roberts suggests, but as libertarian, 27 January 2018

- ↑ The farewell letter written to the woman when Gibson disappeared was part of the file put together by Big Flame on their investigation, as is explained below.

- ↑ Richard Chessum, application for core participant status, 24 November 2017

- ↑ Email from Alastair Renwick and John Lloyd, 5 September 2017

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Email from Richard Chessum, 2 October 2017.

- ↑ In this group, that also included Aly Renwick, Liz Curtis and John Lloyd, the key figure was Géry Lawless. Hence the sectarian Trot groups working to take it over or at least increase their influence, contemptuously referred to us as the 'Lawless grouping'.

- ↑ John Lloyd thinks it wasn't until 1975 that local branch activity took off, and that Rick joined in 1975 and by 1976 he was membership secretary. Richard Chessum is quite sure Rick joined in late 1974, and became secretary soon after.

- ↑ Rick Gibson, Secretariat Convenor, Report of T.O.M. Meeting at L.P.Y.S. Conference, Blackpool, not dated, but probably referring to the conference held in April 1976. There is a reference in Gibson's report to a decision taken at the LCC (London Central Committee?) 23 April 1976. And this article in Red Weekly shows that the cooperation between the TOM and Militant was going to be an important issue at the conference, Red Weekly, LPYS Conference poses the real question: How to fight the right wing, 15 April 1976 (accessed Sep 2017)

- ↑ Email from Richard Chessum, 4 October 2017

- ↑ We are withholding specific details to allow the Inquiry to reach out to any relatives. We asked the Inquiry, on 28 October 2017, to confirm that they had notified the family. They had, at that point, not yet pinpointed the particular child's identity. We have since passed on what we had found out.

- ↑ Alastair Renwick, communication on States Spied in TOM, August 2017

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber/Guardian Books, 2013, p.115

- ↑ Message from Peter Francis, 27 October 2017

- ↑ Nick Davies and Ian Black, The Guardian, 18 April 1984 (microfiche via the Guardian Archive April 2017)

- ↑ Peter Taylor, Transcripts episode 1, True Spies, BBC, 2002, p.3-4 (accessed Oct 2017)

- ↑ Peter Taylor, Transcripts episode 1, True Spies, BBC, 2002, p.5 (accessed Oct 2017)

- ↑ Email from Richard Chessum, 29 September 2017

- ↑ Letter from Peter Taylor, reply to Richard Chessum, 13 March 2003

- ↑ Additional information to be read with the gisted risk assessment for HN302, Undercover Policing Inquiry', 2018, published 8 May 2018 via ucpi.org.uk.

- ↑ MPS, Department of Legal Services, Application for a restriction Order (Anonymity) re: HN297, Metropolitan Police Service (via UCPI.org.uk), 3 July 2017 (accessed 30 August 2017).

- ↑ John Mitting, Applications for restriction orders in respect of the real and cover names of officers of the Special Operations Squad and the Special Demonstrations Squad ‘Minded to’ note, UCPI, 3 August 2017 (accessed 5 Oct 2017)

- ↑ Undercover Policing Inquiry, [https:/www.ucpi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/20171121-Anonymity-application-hearing-day-2-Draft-Transcript.pdf UCPI Preliminary Hearing transcripts], 21 November 2017, p.144-145)

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 Undercover Policing Inquiry, [https:/www.ucpi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/20171121-Anonymity-application-hearing-day-2-Draft-Transcript.pdf UCPI Preliminary Hearing transcripts], 21 November 2017, p.148-149)

- ↑ Undercover Policing Inquiry, [https:/www.ucpi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/20171121-Anonymity-application-hearing-day-2-Draft-Transcript.pdf UCPI Preliminary Hearing transcripts], 21 November 2017, p.6, 146 and 149)

- ↑ Sir John Mitting, Ruling, Undercover Policing Inquiry,5 December 2017 (accessed February 2018)

- ↑ https://www.ucpi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/20180502-transcript.pdf Draft transcript Hearing 5 February 2018], 5 February 2018, p98-99 (accessed February 2018)

- ↑ https://www.ucpi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/20180502-transcript.pdf Draft transcript Hearing 5 February 2018], 5 February 2018. p104-107 and 115 (accessed February 2018)

- ↑ Sir John Mitting, In the matter of section 19(3) of the Inquiries Act 2005 Applications for restriction orders in respect of the real and cover names of officers of the Special Operations Squad and the Special Demonstrations Squad - Ruling, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 20 February 2018 (accessed 4 March 2018).

- ↑ Kate Wilkinson, Counsel to the Inquiry's Explanatory Note to accompany the Chairman's 'Minded-To' Note 12 in respect of applications for restrictions over the real and cover names of officers of the Special Operations Squad and the Special Demonstration Squad, Undercover Public Inquiry, 13 September 2018.

- ↑ Phillippa Kaufmann, QC & Ruth Brander, Submissions on behalf of the Non-Police, Non-State Core Participants re the Chairman's 'Minded To' note dated 3 August 2017 concerning restriction order applications, 5 October 2017 (accessed 3 February 2018 via UCPI.org.uk).

- ↑ Tamsin Allen, Witness Statement of Tamsin Allen, Bindmans Solicitors, 18 December 2017 (accessed via UCPI.org.uk 3 February 2018).

- ↑ Jonathan Hall, QC, Amy Mannion & Reka Hollos, MPS Submissions Hearing 5 February 2018, Metropolitan Police Service, 1 February 2018 (accessed via UCPI.org.uk 3 February 2018).

- ↑ Robert Mark, Wikipedia, undated (accessed 10 October 2017.

- ↑ See Colin Woods &Jock Wilson (police officer), Wikipedia, 2017 (accessed 10 October 2017).

- ↑ Ray Wilson & Ian Adams, Special Branch - A History: 1883-2006, Biteback Publications, 2015.