Difference between revisions of "The God that Failed"

(New page: [[Image:Cold war unicorns eh?.jpg|thumb|right|Cold War Unicorns, a satirical high concept toy playing on themes much like TGTF<ref>The image of the 'Cold War Unicorns ("Can the Communist U...) |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 13:31, 1 May 2009

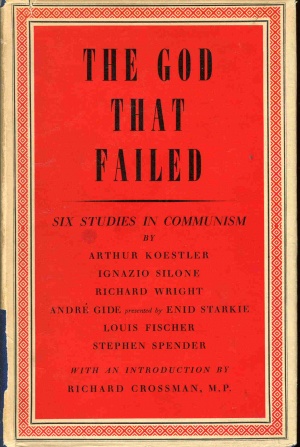

The God That Failed is a book first published in 1949 that collects together essays from authors who were disillusioned with communism. According to a review of a re-issue of the book,[2] in the Council on Foreign Relations magazine Foreign Affairs, it was conceived "in the heat of argument" between Richard Crossman, a British Labour intellectual and politician, and the leftist author Arthur Koestler:

- these essays by six intellectuals "describe the journey into communism, and the return." The only comparable books about the appeals and delusions of communism on idealists outside the Soviet Union are Raymond Aron's Opium of the Intellectuals (1957) and Francois Furet's more recent Le passé d'une illusion (1995). But Aron is more didactic — superbly so — and Furet concentrates on the French case. What makes The God That Failed so powerful is the ardent, bitter, irreplaceable testimony of men like Ignazio Silone, Stephen Spender, Koestler, and Richard Wright — men of very different backgrounds and experiences, all attracted by the "glimpse of the Promised Land" (Koestler), in search of a faith, indeed of "a conversion, a complete dedication" (Silone), of "a state of historical-materialist grace" (Spender). How the dream of fraternity and social justice turns into a nightmare of servility to party double talk and sudden turns, how the fellow traveler drops out and has to return to his own lonely road, is a story that forms a sad, major part of twentieth-century life, in Western Europe and elsewhere.

Louis Fischer, one of two American contributors, took offence when he was labeled an ex-communist, because he had never joined a Communist Party, having only been sympathetic to the Soviet cause. In a note for a biographical entry, he referred to himself as a “left-of-center liberal who favors drastic social reform to improve living conditions” and an “active anti-imperialist.”[3]

The God that Failed (TGTF) has become something of a historical artifact, with the phrase being used to express any disgruntlement with a supposed orthodoxy imposed by others. The mythology around it is often used as a talisman by anti-communists. It was cited in this way in the final editorial of The Nation:

- the bankruptcy of communism was plain to anybody who had waited so long to be convinced. It had been pronounced long before by men who had been and remained progressively liberal and idealistic – Keynes himself, Orwell, Edmund Wilson (Marxism at the end of the thirties) and R. H. S. Crossman (The God that Failed). They were the kind of men from whom Nation drew encouragement.[4]

History

The first edition appeared in 1949/50 and TGTF was continually reprinted until the late 1970s. In the 1980s, Regnery published the collection with an introduction by Norman Podhoretz, who decried the authors' failure to choose the liberal West as the logical alternative to communism. A 2001 edition comes from Columbia University Press, with an introduction by the historian David C. Engerman, who states that it "defined a new paradigm for Western intellectual life in the Cold War: American-centered, closely tied to political power, and staunchly anti-Soviet."[5]

TGTF emerged at a period when the CIA's strategy of promoting the 'non-Communist left' (NCL) was to the fore and, alongside Arthur Schlesinger's The Vital Center and Orwell's 1984, it became used as a promotion of the 'NCL'. For Frances Stonor Saunders, the

- history of its publication serves as a template for the contract between the Non-Communist Left and the "dark angel" of American government. By the summer of 1948, Koestler had discussed the idea with Richard Crossman, wartime head of the German section of the Psychological Warfare Executive (PWE), a man who felt "he could manipulate masses of people", and who had "just the right amount of intellectual sleight-of-hand to make him a perfect professional propagandist".[6]

She adds that Crossman involved another psychological warfare veteran, the American C. D. Jackson, in the project, quoting a letter from Crossman:

- I am writing to ask your advice. Cass Canfield of Harpers, and Hamish Hamilton, my publisher here, are proposing next spring to publish a book called Lost Illusions, for which I have taken editorial responsibility. It is to consist of a series of autobiographical sketches by prominent intellectuals, describing how they became Communists or fellow-travelers, what made them feel that Communism was the hope of the world, and what disillusioned them.[7]

Crossman then approached Melvin Lasky, at the time America's "official unofficial cultural propagandist" in Germany, and one of the earliest advocates of organized intellectual resistance to Communism. As Crossman received contributions for the book, he sent them immediately on to Lasky, who had them translated in the offices of Der Monat, the German monthly magazine Lasky had founded in 1948. Der Monat was funded by the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), an anti-communist organisation established in 1950 that received funds from the CIA.[8]

Saunders argues that with this background, TGTF was "as much a product of intelligence as it was a work of the intelligentsia." Its contributors were former propagandists for the Soviets and now, embraced by government strategists, their "conversion" proved an irresistible opportunity "to sabotage the Soviet propaganda machine which they had once oiled".[9] Saunders writes:

- "The God That Failed gang" was now a nomenclature adopted by the CIA, denoting what one officer called 'that community of intellectuals who were disillusioned, who could be disillusioned, or who hadn't taken a position yet, and who could to some degree be influenced by their peers as to what choice to make'. The God That Failed was distributed by US government agencies all over Europe. In Germany, in particular, it was rigorously promoted. The Information Research Department also pushed the book. Koestler was happy. His plans for a strategically organized response to the Soviet threat were coalescing nicely. Whilst the book was rolling off the presses, he met with Melvin Lasky to discuss something more ambitious, more permanent.[10]

The Information Research Department

In the mid-90s the UK's Public Record Office released files documenting the first years of existence of the Information Research Department (IRD). A secret organization, its larger purpose was to gather confidential information about communism and produce factually based anti-communist propaganda for dissemination both abroad and at home. Recipients of its unattributable output included a number of prominent politicians, trade unionists, journalists and intellectuals. Employing as many as 300 staff at the height of the Cold War in the 1950s, IRD was scaled down considerably during the 1970s, until being closed in 1977 by the Labour Foreign Secretary David Owen.[11]

References, Resources

- ↑ The image of the 'Cold War Unicorns ("Can the Communist Unicorn’s horn of classless social structure hold up against the Freedom Unicorn’s hooves of capitalist opportunity?") is from Archie McPhee's website.

- ↑ Stanley Hoffmann, Foreign Affairs, September/October 1997

- ↑ Louis Fischer Papers, 1890-1977 (bulk 1935-1969)

- ↑ Final editorial by Tom Fitzgerald from Nation, 22 July 1972 Flourish, Nation Review.

- ↑ Alan Charles Kors, Rose-Colored Glasses: What even disillusioned Marxists missed, Reasononline, April 2002, accessed March 2009

- ↑ Frances Stonor Saunders, Who Paid The Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War', Granta, 1999

- ↑ Frances Stonor Saunders, Who Paid The Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War', Granta, 1999

- ↑ "Melvin J. Lasky, Cold Warrior editor of the controversially funded 'Encounter'", The Independent, 21 May 2004, accessed November 2008

- ↑ Frances Stonor Saunders, Who Paid The Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War', Granta, 1999

- ↑ Frances Stonor Saunders, Who Paid The Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War', Granta, 1999, pp. 63-66.

- ↑ Hugh Wilford (1998) "The Information Research Department: Britain’s secret Cold War weapon revealed", (Abstract only: full article available by subscription), Review of International Studies, 24, pp. 353–369