Difference between revisions of "Edward Lansdale"

(→The Mongoose in the Pentagon goes to Cuba) |

Tom Griffin (talk | contribs) (last summary in error - External Resources/category OSS, CIA) |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | ::"His battles were over ideas and his weapons were the tools to convince, not kill. His influence with Asians came more from his preference to listen to them than from a compulsion to tell them, an unfortunately rare attribute among the other Americans they knew. He was more interested in their songs and stories than in their armaments and believed the people's rich traditions and history were more important than their military's stockpiles in the long run." | + | <blockquote style="background;border:1pt solid;padding:1%">"His battles were over ideas and his weapons were the tools to convince, not kill. His influence with Asians came more from his preference to listen to them than from a compulsion to tell them, an unfortunately rare attribute among the other Americans they knew. He was more interested in their songs and stories than in their armaments and believed the people's rich traditions and history were more important than their military's stockpiles in the long run." |

| − | + | - Former CIA director [[William Colby|William E. Colby]] on Lansdale <ref>From his introduction to Cecil Currey's biography of Lansdale, quoted from [http://faculty.buffalostate.edu/fishlm/folksongs/lansdale.pdf Lydia M. Fish (1989) General Edward G. Lansdale and the Folksongs of Americans in the Vietnam War, Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 102 October-December, No. 406.]</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote style="background;border:1pt solid;padding:1%">"That guy's a dingbat..." - Al Haig on Lansdale <ref>Don Bohning (2004)The Castro Obsession: U.S. Covert Operations Against Cuba, 1959-1965, page 86.</ref></blockquote> | |

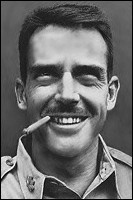

| + | [[Image:Lansdale.jpg|right|thumb|Edward Lansdale]] '''Edward Geary Lansdale''', was an Air Force officer whose influential theories of counterinsurgent warfare were developed in the Philippines after World War II and again in South Vietnam. Lansdale is rumoured to have inspired characters in two novels involving guerrilla warfare: the prototype for novelist Graham Greene's character Alden Pyle in ''The Quiet American'' (1955), and the inspiration for William Lederer and Eugene Burdick's ''The Ugly American'' (1958), as well as these works' subsequent Hollywood film adaptations, although the accuracy of this is disputed. | ||

| − | + | ==Career== | |

| + | Lansdale was born on 6 February 1908, and after university became an advertising executive. He joined the Army as a captain in 1943 and rose to major by 1947, when he left the Army. During World War II he also served in the [[Office of Strategic Services]]. He joined the Air Force as a captain the same year, he went to Vietnam in 1954 as a CIA operative and helped in setting up the South Vietnamese Government of President Ngo Dinh Diem, who was overthrown and killed in a coup in 1963. Lansdale was head of a team of agents that carried out undercover operations against North Vietnam. The team turned in a vivid report of its actions shortly before pulling out of Hanoi in October 1954 after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu. The team's report, later included among the [[Pentagon Papers]].<ref>[http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pentagon2/doc100.htm Excerpts from memorandum from Brig. Gen. Edward G. Lansdale, Pentagon expert on guerrilla warfare, to Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, President Kennedy's military adviser, on "Resources for Unconventional Warfare, SE. Asia," undated but apparently from July, 1961] see also [http://www.clemson.edu/caah/history/facultypages/EdMoise/pentagon.html Vietnam War Bibliography: The Pentagon Papers.]</ref> | ||

| − | + | Lansdale was posted to the Pentagon in 1956 and there, by some accounts, assisted in the formation of the Special Forces, which had the special patronage of President Kennedy. | |

| + | |||

| + | He also served as the director of the CIA's undercover operations in Indochina. | ||

| − | : | + | In a 1977 book, ''In the Midst of Wars: An American's Mission to Southeast Asia'', Lansdale argued that the United States could still prevail in remote third-world nations by exporting "the American way" through a blend of economic aid and efforts at "winning the hearts and the minds of the people." <ref>Eric Pace, [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DE1D8153BF937A15751C0A961948260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=print ‘Edward Lansdale at 79; Advisor on guerrilla warfare’], ''New York Times'', 24 February 1987</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | === Philippines advisor === | ||

| + | Lansdale acted as an adviser in the newly independent Philippines in the late 1940s and early 1950s and was an influence in operations by the Philippine leader Ramon Magsaysay against the Communist-dominated Hukbalahap rebellion. John Ranelagh's 1987 book ''The Agency''<ref>John Ranelagh, ''The Agency: The Rise and Decline of the CIA'' (New York Simon and Schuster, 1987), see pages 224-225 on Lansdale's use of proxy forces, counter-gangs and the creation of 'nation-building features such as 'the National Movement for Free Elections and pseudo-civic organisations such as 'Magsaysay for President'. Lansdale's [http://www.af.mil/bios/bio.asp?bioID=6141 Airforce biography] makes no mention of the CIA.</ref> states that in 1950-53 Lansdale was on loan to the CIA from the Airforce when advising Ramon Magsaysay as part of the major long-term project of keeping Communists from power in the far east and take over the old empires in Southeast Asia rather than ally itself with the nascent nationalist and independence movements identified by CIA analists previously: this also represented a shift away from Europe. <ref>John Ranelagh, ''The Agency: The Rise and Decline of the CIA'' (New York Simon and Schuster, 1987), see page 226</ref> Here he was working in the Office of Policy Co-ordination (OPC) itself set up in 1948 as a result of National Security Council directive 10/2 whereby the newly formed CIA could engage in "covert operations" in such a manner that: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%">all activities conducted pursuant to this directive which are so planned and executed that any U.S. Government responsibility for them is not evident to unauthorized persons and that if uncovered the U.S. Government can plausibly disclaim any responsibility for them.</blockquote> | |

| − | + | The directive states that: | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%">Specifically, such operations shall include any covert activities related to: propaganda, political action; economic warfare; preventive direct action, including sabotage, anti-sabotage, demolition; escape and evasion and evacuation measures; subversion against hostile states or groups including assistance to underground resistance movements, guerrillas and refugee liberation groups; support of indigenous and anti-communist elements in threatened countries of the free world; deceptive plans and operations; and all activities compatible with this directive necessary to accomplish the foregoing. Such operations shall not include: armed conflict by recognized military forces, espionage and counterespionage, nor cover and deception for military operations.<ref>http://www.ratical.org/ratville/JFK/USO/appC.html see also http://cryptome.org/ic-black4701.htm</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | + | According to the ''New York Times'' obituary: | |

| − | : | + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%">It was in the Philippines that General Lansdale framed his basic theory, that Communist revolution was best confronted by democratic revolution. He came to advocate a four-sided campaign, with social, economic and political aspects as well as purely military operations. He put much emphasis on what came to be called civic-action programs to undermine Filipinos' backing for the Huks. |

| + | Looking back on what he learned in Asia, he once said: "The Communists strive to split the people away from the Government and gain control over a decisive number of the population. The sure defense against this strategy is to have the citizenry and the Government so closely bound together that they are unsplittable.<ref>Eric Pace, [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DE1D8153BF937A15751C0A961948260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=print ‘Edward Lansdale at 79; Advisor on guerrilla warfare’], ''New York Times'', 24 February 1987</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | Lansdale | + | === In Vietnam === |

| + | Lansdale became an adviser to South Vietnamese and United States military leaders, and also to Ambassador [[Henry Cabot Lodge]]. The Times obituary argues that he made efforts to generate popular support for the embattled Saigon Government, at a time when the United States military role in Vietnam remained limited, and that this "failed to forestall an escalation of the insurgency to full-scale conventional warfare". | ||

| − | + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%">Early in the war, General Lansdale was considered to be the individual who provided the intellectual direction to the counterinsurgency and nation-building efforts. But he became less significant when the conflict left the counterinsurgency phase and became a more conventional war.<ref>Eric Pace, [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DE1D8153BF937A15751C0A961948260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=print ‘Edward Lansdale at 79; Advisor on guerrilla warfare’], ''New York Times'', 24 February 1987</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | Lansdale was | + | === Operation Mongoose === |

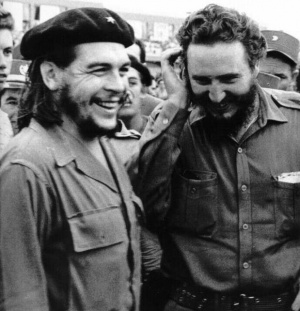

| + | [[Image:Che fidel.jpg|left|thumb|Two assassination targets of US covert operations]] | ||

| + | In 1961 Lansdale was told by the Kennedy Administration to draft a contingency plan to overthrow President Fidel Castro of Cuba. This was to become the infamous "Operation Mongoose" and Lansdale's (1962)"Operation Mongoose: Program Review by the Chief of Operations," prepared for the U.S., Department of State, which was once secret is now online.<ref>Edward Lansdale's (1962)[http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/cold-war/mongoose.htm "Operation Mongoose: Program Review by the Chief of Operations,"] prepared for the U.S., Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States 1961-1963, Volume X Cuba, 1961-1962).</ref> | ||

| − | + | John Ranelagh notes some of the many peculiarities of the operation: | |

| − | + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%">The Mongoose team came up with thirty-three different plans to do "something" about Castro. Included in these schemes were intelligence collection, the use of armed force, and biological and chemical attacks on the Cuban sugar crop. One of the more creative plans involved an attempt to convince Cuba's large Roman Catholic population that the Second Coming was soon and that Christ would return in Cuba if the Cubans got rid of Castro, the anti-Christ, first. This particular idea was Lansdale's. He had conducted a similar scheme in the Philippines during the anti-Huk campaign, using helicopters fitted with loudspeakers to broadcast to primitive tribesmen from the sky. In the case of the more advanced Cuba, rumors were to be circulated in the country that the Second Coming was actually going to take place in Cuba very soon. Once these rumors had taken hold and, it was hoped, generated a popular uprising against Castro, a U.S. submarine off the Cuban coast would fill the night sky with star shells. This display would be taken as indicating that Christ was on his way by the natives, who would promptly complete the overthrow of Castro. "Elimination by illumination," was what Walt Elder, McCone's executive assistant, termed this scheme, which was too fanciful even for the Mongoose team and was not implemented."<ref>John Ranelagh (1987)'The Agency', see page 386.</ref></blockquote> | |

| + | Mongoose followed the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion President Kennedy named his brother, United States Attorney General Robert Kennedy, to oversee Operation Mongoose in cooperation with Kennedy's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, a group of civilian experts on foreign relations. Here several senior CIA officials allegedly began working with members of the mafia. The mafia would give the CIA 'plausible deniability' if an assassination plot were uncovered. Mongoose (and the Bay of Pigs) was a continuation of a secret operation against the Cuban regime that began during the Eisenhower Administration. The component of Mongoose that Lansdale oversaw (as far as can be determined from released material) was the psychological warfare or 'PsyOps' aspect of Operation Mongoose. | ||

| − | = | + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%">Lansdale created an anti-Castro radio broadcast that covertly aired in Cuba. Leaflets were distributed that depicted Castro as getting fat and wealthy at the expense of citizens. Operatives circulated stories about heroic freedom fighters. Yet, the main thrust of Lansdale's plans was a series of large scale "dirty tricks" meant to evoke a call to arms against Cuba in the international community. One plan called for a space launch at Cape Canaveral to be sabotaged and blamed on Cuban agents. Operation Bingo called for a staged attack on the U.S. Navy Base at Guantanamo Bay in hopes of creating a mandate for the U.S. military to overthrow Castro. When the Church Committee investigated the actions of the national intelligence agencies in the wake of the Watergate scandal in 1974, notes on Operation Mongoose surfaced for the first time. The committee commented not only on the assassination plots, but also noted the "dirty tricks" proposed by Lansdale. Little else was revealed about the operation for three more decades.<ref>http://www.espionageinfo.com/Nt-Pa/Operation-Mongoose.html</ref></blockquote> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Other sources indicate that the use of the 'mafia' was an integral consideration in the plan: | |

| − | :" | + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%">Utilizing his authority to employ all available means in the project, Lansdale openly spelled out the tasks of different agencies involved —tasks that had already been undertaken covertly but had not been put in writing in documents such as this. These included a proposal that the CIA undertake "bold new actions" and that it utilize the "potential of the underworld" and, in close cooperation with the FBI, "enlist the assistance of American links" to the Mafia in Cuba.<ref>http://www.themilitant.com/2002/6637/663750.html</ref></blockquote> |

| + | ==Cultural significance== | ||

Some writers see American Cold War culture and the complex ways in which Lansdale both embodied and helped to shape it in terms of Lansdale as the career military officer and advisor, and Lansdale as Cold War celebrity; a combination which points to the interface of PR and military propaganda and covert operations: | Some writers see American Cold War culture and the complex ways in which Lansdale both embodied and helped to shape it in terms of Lansdale as the career military officer and advisor, and Lansdale as Cold War celebrity; a combination which points to the interface of PR and military propaganda and covert operations: | ||

| − | :Using the artistic skills he developed in college and his experience in advertising, Lansdale became the ultimate confidence man, "combining American belief systems with the persuasive forces of money and military strength" [...] Lansdale was caught between liberal and warrior values. The career Air Force officer and apparent operative for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) empathized with the colonial struggle, and had an anthropologist-like interest in the cultures and history of Southeast Asia. Lansdale sought knowledge of Asian culture through his experiences, and then attempted to use that cultural knowledge to benefit American policy. Simultaneously, Lansdale used illiberal tactics (advertising schemes, propaganda, black operations, rigged elections, counterinsurgency) to put American policy into practice in Southeast Asia. As a result, Lansdale accrued a tremendous amount of power helping the governments of the Philippines and South Vietnam in the 1950s and 1960s. The heads of these two governments, Ramon Magsaysay and Ngo Dinh Diem, respectively, gave Lansdale tremendous latitude to create "layer upon layer of confidence schemes mobilized by the power of publicity" (p. 72) so as to win the hearts and minds of the people in the struggle against the spread of communism. Lansdale assumed that these plans, which met limited success in Vietnam and failed in Cuba, would ensure the success of American-style democracy.<ref>Jonathan Nashel. Edward Lansdale's Cold War. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005. [http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=12661 Reviewed by Charles J. Pellegrin | + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%">Using the artistic skills he developed in college and his experience in advertising, Lansdale became the ultimate confidence man, "combining American belief systems with the persuasive forces of money and military strength" [...] Lansdale was caught between liberal and warrior values. The career Air Force officer and apparent operative for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) empathized with the colonial struggle, and had an anthropologist-like interest in the cultures and history of Southeast Asia. Lansdale sought knowledge of Asian culture through his experiences, and then attempted to use that cultural knowledge to benefit American policy. Simultaneously, Lansdale used illiberal tactics (advertising schemes, propaganda, black operations, rigged elections, counterinsurgency) to put American policy into practice in Southeast Asia. As a result, Lansdale accrued a tremendous amount of power helping the governments of the Philippines and South Vietnam in the 1950s and 1960s. The heads of these two governments, Ramon Magsaysay and Ngo Dinh Diem, respectively, gave Lansdale tremendous latitude to create "layer upon layer of confidence schemes mobilized by the power of publicity" (p. 72) so as to win the hearts and minds of the people in the struggle against the spread of communism. Lansdale assumed that these plans, which met limited success in Vietnam and failed in Cuba, would ensure the success of American-style democracy.<ref>Jonathan Nashel. Edward Lansdale's Cold War. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005. [http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=12661 Reviewed by Charles J. Pellegrin on H-War, H-Net Reviews], December 2006</ref></blockquote> |

| − | In a sense this mythology links back to the 'The Quiet American' and 'The Ugly American' duality. Nashel (quoted above) contends that Lansdale hoped he could utilize this celebrity to carry out the "selling" of South Vietnam to the Americans and includes a verbatim transcript of a March 1956 letter from Lansdale to Joseph Mankiewicz (the director of the 1958 film version of The Quiet American) that suggested screenplay changes to make Vietnam a much more attractive locale and to place the communists in a more negative light, thereby "transforming the ideological purposes of a novel whose politics and tone he despised into a film he could enjoy." | + | In a sense this mythology links back to the ''The Quiet American'' and ''The Ugly American'' duality. Nashel (quoted above) contends that Lansdale hoped he could utilize this celebrity to carry out the "selling" of South Vietnam to the Americans and includes a verbatim transcript of a March 1956 letter from Lansdale to Joseph Mankiewicz (the director of the 1958 film version of ''The Quiet American'') that suggested screenplay changes to make Vietnam a much more attractive locale and to place the communists in a more negative light, thereby "transforming the ideological purposes of a novel whose politics and tone he despised into a film he could enjoy." |

| + | |||

| + | L. Fletcher Prouty alleges that it was Lansdale's job to provide "actors", and "screenplays" for certain black operations deployed by the covert operatives and extends this into the incredible assertion that he believes that the a man walking away from the camera in a photograph of a group of 'tramps' taken after Kennedy was assassinated is Edward Lansdale— who finds Prouty somewhat paranoid.<ref>http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/COLDlansdale.htm</ref> | ||

[[Daniel Ellsberg]] the author of 'The Pentagon Papers' served with Lansdale in the mid to late 1960s as a member of Lansdale's senior liaison office of elite intelligence agents and with with Henry Kissinger —his former teacher: | [[Daniel Ellsberg]] the author of 'The Pentagon Papers' served with Lansdale in the mid to late 1960s as a member of Lansdale's senior liaison office of elite intelligence agents and with with Henry Kissinger —his former teacher: | ||

| − | :When not engaged in typical RD Program "Civil Affairs" activities, such as helping the local Vietnamese build perimeter defenses around their villages, Ellsberg and his fellow RD advisors, under the tutelage of Lansdale, dressed in black pajamas and reportedly slipped into enemy areas at midnight to "snatch and snuff" the local Viet Cong cadre, sometimes making it appear as if the VC themselves had done the dirty deed, in what Lansdale euphemistically called "black propaganda" activities.<ref>http://www.counterpunch.org/valentine03082003.html</ref> | + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%">When not engaged in typical RD Program "Civil Affairs" activities, such as helping the local Vietnamese build perimeter defenses around their villages, Ellsberg and his fellow RD advisors, under the tutelage of Lansdale, dressed in black pajamas and reportedly slipped into enemy areas at midnight to "snatch and snuff" the local Viet Cong cadre, sometimes making it appear as if the VC themselves had done the dirty deed, in what Lansdale euphemistically called "black propaganda" activities.<ref>http://www.counterpunch.org/valentine03082003.html</ref></blockquote> |

| − | Ellsberg disconcerted government officials by organizing a group of five associates to write a letter to the New York Times and the Washington Post denouncing the war. | + | Ellsberg disconcerted government officials by organizing a group of five associates to write a letter to the ''New York Times'' and the ''Washington Post'' denouncing the war. |

| − | :He began to see not only himself but everyone who did not demonstrated actively against the war as a "war criminal." He seemed obsessed, and his friends found it impossible to get him to talk of other topics; many were put off when he called them "good Germans" for not protesting against the war.<ref>http://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/1996/analysis/back.time/9606/28/index.shtml</ref> | + | <blockquote style="background-color:beige;border:1pt solid Darkgoldenrod;padding:1%">He began to see not only himself but everyone who did not demonstrated actively against the war as a "war criminal." He seemed obsessed, and his friends found it impossible to get him to talk of other topics; many were put off when he called them "good Germans" for not protesting against the war.<ref>http://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/1996/analysis/back.time/9606/28/index.shtml</ref></blockquote> |

This "act of conscience" helped turn public opinion against the Vietnam War, and inadvertently contributed to the demise of President Richard Nixon, when CIA officer [[E. Howard Hunt]], and former FBI agent [[G. Gordon Liddy]], went to burgle confidential files from Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office, and instead opened up the can of worms of the CIA inspired dirty tricks the Republican Party relied upon to wage political warfare. | This "act of conscience" helped turn public opinion against the Vietnam War, and inadvertently contributed to the demise of President Richard Nixon, when CIA officer [[E. Howard Hunt]], and former FBI agent [[G. Gordon Liddy]], went to burgle confidential files from Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office, and instead opened up the can of worms of the CIA inspired dirty tricks the Republican Party relied upon to wage political warfare. | ||

| − | == | + | ==External Resources== |

| + | *Chalmers Johnson, [http://www.lrb.co.uk/v25/n22/chalmers-johnson/the-looting-of-asia The Looting of Asia], ''London Review of Books'', 20 November 2003. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| + | [[Category:counterinsurgency|Lansdale, Edward]][[Category:OSS|Lansdale, Edward]] | ||

| + | [[Category:CIA|Lansdale, Edward]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:52, 8 July 2012

"His battles were over ideas and his weapons were the tools to convince, not kill. His influence with Asians came more from his preference to listen to them than from a compulsion to tell them, an unfortunately rare attribute among the other Americans they knew. He was more interested in their songs and stories than in their armaments and believed the people's rich traditions and history were more important than their military's stockpiles in the long run." - Former CIA director William E. Colby on Lansdale [1]

"That guy's a dingbat..." - Al Haig on Lansdale [2]

Edward Geary Lansdale, was an Air Force officer whose influential theories of counterinsurgent warfare were developed in the Philippines after World War II and again in South Vietnam. Lansdale is rumoured to have inspired characters in two novels involving guerrilla warfare: the prototype for novelist Graham Greene's character Alden Pyle in The Quiet American (1955), and the inspiration for William Lederer and Eugene Burdick's The Ugly American (1958), as well as these works' subsequent Hollywood film adaptations, although the accuracy of this is disputed.

Contents

Career

Lansdale was born on 6 February 1908, and after university became an advertising executive. He joined the Army as a captain in 1943 and rose to major by 1947, when he left the Army. During World War II he also served in the Office of Strategic Services. He joined the Air Force as a captain the same year, he went to Vietnam in 1954 as a CIA operative and helped in setting up the South Vietnamese Government of President Ngo Dinh Diem, who was overthrown and killed in a coup in 1963. Lansdale was head of a team of agents that carried out undercover operations against North Vietnam. The team turned in a vivid report of its actions shortly before pulling out of Hanoi in October 1954 after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu. The team's report, later included among the Pentagon Papers.[3]

Lansdale was posted to the Pentagon in 1956 and there, by some accounts, assisted in the formation of the Special Forces, which had the special patronage of President Kennedy.

He also served as the director of the CIA's undercover operations in Indochina.

In a 1977 book, In the Midst of Wars: An American's Mission to Southeast Asia, Lansdale argued that the United States could still prevail in remote third-world nations by exporting "the American way" through a blend of economic aid and efforts at "winning the hearts and the minds of the people." [4]

Philippines advisor

Lansdale acted as an adviser in the newly independent Philippines in the late 1940s and early 1950s and was an influence in operations by the Philippine leader Ramon Magsaysay against the Communist-dominated Hukbalahap rebellion. John Ranelagh's 1987 book The Agency[5] states that in 1950-53 Lansdale was on loan to the CIA from the Airforce when advising Ramon Magsaysay as part of the major long-term project of keeping Communists from power in the far east and take over the old empires in Southeast Asia rather than ally itself with the nascent nationalist and independence movements identified by CIA analists previously: this also represented a shift away from Europe. [6] Here he was working in the Office of Policy Co-ordination (OPC) itself set up in 1948 as a result of National Security Council directive 10/2 whereby the newly formed CIA could engage in "covert operations" in such a manner that:

all activities conducted pursuant to this directive which are so planned and executed that any U.S. Government responsibility for them is not evident to unauthorized persons and that if uncovered the U.S. Government can plausibly disclaim any responsibility for them.

The directive states that:

Specifically, such operations shall include any covert activities related to: propaganda, political action; economic warfare; preventive direct action, including sabotage, anti-sabotage, demolition; escape and evasion and evacuation measures; subversion against hostile states or groups including assistance to underground resistance movements, guerrillas and refugee liberation groups; support of indigenous and anti-communist elements in threatened countries of the free world; deceptive plans and operations; and all activities compatible with this directive necessary to accomplish the foregoing. Such operations shall not include: armed conflict by recognized military forces, espionage and counterespionage, nor cover and deception for military operations.[7]

According to the New York Times obituary:

It was in the Philippines that General Lansdale framed his basic theory, that Communist revolution was best confronted by democratic revolution. He came to advocate a four-sided campaign, with social, economic and political aspects as well as purely military operations. He put much emphasis on what came to be called civic-action programs to undermine Filipinos' backing for the Huks. Looking back on what he learned in Asia, he once said: "The Communists strive to split the people away from the Government and gain control over a decisive number of the population. The sure defense against this strategy is to have the citizenry and the Government so closely bound together that they are unsplittable.[8]

In Vietnam

Lansdale became an adviser to South Vietnamese and United States military leaders, and also to Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge. The Times obituary argues that he made efforts to generate popular support for the embattled Saigon Government, at a time when the United States military role in Vietnam remained limited, and that this "failed to forestall an escalation of the insurgency to full-scale conventional warfare".

Early in the war, General Lansdale was considered to be the individual who provided the intellectual direction to the counterinsurgency and nation-building efforts. But he became less significant when the conflict left the counterinsurgency phase and became a more conventional war.[9]

Operation Mongoose

In 1961 Lansdale was told by the Kennedy Administration to draft a contingency plan to overthrow President Fidel Castro of Cuba. This was to become the infamous "Operation Mongoose" and Lansdale's (1962)"Operation Mongoose: Program Review by the Chief of Operations," prepared for the U.S., Department of State, which was once secret is now online.[10]

John Ranelagh notes some of the many peculiarities of the operation:

The Mongoose team came up with thirty-three different plans to do "something" about Castro. Included in these schemes were intelligence collection, the use of armed force, and biological and chemical attacks on the Cuban sugar crop. One of the more creative plans involved an attempt to convince Cuba's large Roman Catholic population that the Second Coming was soon and that Christ would return in Cuba if the Cubans got rid of Castro, the anti-Christ, first. This particular idea was Lansdale's. He had conducted a similar scheme in the Philippines during the anti-Huk campaign, using helicopters fitted with loudspeakers to broadcast to primitive tribesmen from the sky. In the case of the more advanced Cuba, rumors were to be circulated in the country that the Second Coming was actually going to take place in Cuba very soon. Once these rumors had taken hold and, it was hoped, generated a popular uprising against Castro, a U.S. submarine off the Cuban coast would fill the night sky with star shells. This display would be taken as indicating that Christ was on his way by the natives, who would promptly complete the overthrow of Castro. "Elimination by illumination," was what Walt Elder, McCone's executive assistant, termed this scheme, which was too fanciful even for the Mongoose team and was not implemented."[11]

Mongoose followed the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion President Kennedy named his brother, United States Attorney General Robert Kennedy, to oversee Operation Mongoose in cooperation with Kennedy's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, a group of civilian experts on foreign relations. Here several senior CIA officials allegedly began working with members of the mafia. The mafia would give the CIA 'plausible deniability' if an assassination plot were uncovered. Mongoose (and the Bay of Pigs) was a continuation of a secret operation against the Cuban regime that began during the Eisenhower Administration. The component of Mongoose that Lansdale oversaw (as far as can be determined from released material) was the psychological warfare or 'PsyOps' aspect of Operation Mongoose.

Lansdale created an anti-Castro radio broadcast that covertly aired in Cuba. Leaflets were distributed that depicted Castro as getting fat and wealthy at the expense of citizens. Operatives circulated stories about heroic freedom fighters. Yet, the main thrust of Lansdale's plans was a series of large scale "dirty tricks" meant to evoke a call to arms against Cuba in the international community. One plan called for a space launch at Cape Canaveral to be sabotaged and blamed on Cuban agents. Operation Bingo called for a staged attack on the U.S. Navy Base at Guantanamo Bay in hopes of creating a mandate for the U.S. military to overthrow Castro. When the Church Committee investigated the actions of the national intelligence agencies in the wake of the Watergate scandal in 1974, notes on Operation Mongoose surfaced for the first time. The committee commented not only on the assassination plots, but also noted the "dirty tricks" proposed by Lansdale. Little else was revealed about the operation for three more decades.[12]

Other sources indicate that the use of the 'mafia' was an integral consideration in the plan:

Utilizing his authority to employ all available means in the project, Lansdale openly spelled out the tasks of different agencies involved —tasks that had already been undertaken covertly but had not been put in writing in documents such as this. These included a proposal that the CIA undertake "bold new actions" and that it utilize the "potential of the underworld" and, in close cooperation with the FBI, "enlist the assistance of American links" to the Mafia in Cuba.[13]

Cultural significance

Some writers see American Cold War culture and the complex ways in which Lansdale both embodied and helped to shape it in terms of Lansdale as the career military officer and advisor, and Lansdale as Cold War celebrity; a combination which points to the interface of PR and military propaganda and covert operations:

Using the artistic skills he developed in college and his experience in advertising, Lansdale became the ultimate confidence man, "combining American belief systems with the persuasive forces of money and military strength" [...] Lansdale was caught between liberal and warrior values. The career Air Force officer and apparent operative for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) empathized with the colonial struggle, and had an anthropologist-like interest in the cultures and history of Southeast Asia. Lansdale sought knowledge of Asian culture through his experiences, and then attempted to use that cultural knowledge to benefit American policy. Simultaneously, Lansdale used illiberal tactics (advertising schemes, propaganda, black operations, rigged elections, counterinsurgency) to put American policy into practice in Southeast Asia. As a result, Lansdale accrued a tremendous amount of power helping the governments of the Philippines and South Vietnam in the 1950s and 1960s. The heads of these two governments, Ramon Magsaysay and Ngo Dinh Diem, respectively, gave Lansdale tremendous latitude to create "layer upon layer of confidence schemes mobilized by the power of publicity" (p. 72) so as to win the hearts and minds of the people in the struggle against the spread of communism. Lansdale assumed that these plans, which met limited success in Vietnam and failed in Cuba, would ensure the success of American-style democracy.[14]

In a sense this mythology links back to the The Quiet American and The Ugly American duality. Nashel (quoted above) contends that Lansdale hoped he could utilize this celebrity to carry out the "selling" of South Vietnam to the Americans and includes a verbatim transcript of a March 1956 letter from Lansdale to Joseph Mankiewicz (the director of the 1958 film version of The Quiet American) that suggested screenplay changes to make Vietnam a much more attractive locale and to place the communists in a more negative light, thereby "transforming the ideological purposes of a novel whose politics and tone he despised into a film he could enjoy."

L. Fletcher Prouty alleges that it was Lansdale's job to provide "actors", and "screenplays" for certain black operations deployed by the covert operatives and extends this into the incredible assertion that he believes that the a man walking away from the camera in a photograph of a group of 'tramps' taken after Kennedy was assassinated is Edward Lansdale— who finds Prouty somewhat paranoid.[15]

Daniel Ellsberg the author of 'The Pentagon Papers' served with Lansdale in the mid to late 1960s as a member of Lansdale's senior liaison office of elite intelligence agents and with with Henry Kissinger —his former teacher:

When not engaged in typical RD Program "Civil Affairs" activities, such as helping the local Vietnamese build perimeter defenses around their villages, Ellsberg and his fellow RD advisors, under the tutelage of Lansdale, dressed in black pajamas and reportedly slipped into enemy areas at midnight to "snatch and snuff" the local Viet Cong cadre, sometimes making it appear as if the VC themselves had done the dirty deed, in what Lansdale euphemistically called "black propaganda" activities.[16]

Ellsberg disconcerted government officials by organizing a group of five associates to write a letter to the New York Times and the Washington Post denouncing the war.

He began to see not only himself but everyone who did not demonstrated actively against the war as a "war criminal." He seemed obsessed, and his friends found it impossible to get him to talk of other topics; many were put off when he called them "good Germans" for not protesting against the war.[17]

This "act of conscience" helped turn public opinion against the Vietnam War, and inadvertently contributed to the demise of President Richard Nixon, when CIA officer E. Howard Hunt, and former FBI agent G. Gordon Liddy, went to burgle confidential files from Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office, and instead opened up the can of worms of the CIA inspired dirty tricks the Republican Party relied upon to wage political warfare.

External Resources

- Chalmers Johnson, The Looting of Asia, London Review of Books, 20 November 2003.

Notes

- ↑ From his introduction to Cecil Currey's biography of Lansdale, quoted from Lydia M. Fish (1989) General Edward G. Lansdale and the Folksongs of Americans in the Vietnam War, Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 102 October-December, No. 406.

- ↑ Don Bohning (2004)The Castro Obsession: U.S. Covert Operations Against Cuba, 1959-1965, page 86.

- ↑ Excerpts from memorandum from Brig. Gen. Edward G. Lansdale, Pentagon expert on guerrilla warfare, to Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, President Kennedy's military adviser, on "Resources for Unconventional Warfare, SE. Asia," undated but apparently from July, 1961 see also Vietnam War Bibliography: The Pentagon Papers.

- ↑ Eric Pace, ‘Edward Lansdale at 79; Advisor on guerrilla warfare’, New York Times, 24 February 1987

- ↑ John Ranelagh, The Agency: The Rise and Decline of the CIA (New York Simon and Schuster, 1987), see pages 224-225 on Lansdale's use of proxy forces, counter-gangs and the creation of 'nation-building features such as 'the National Movement for Free Elections and pseudo-civic organisations such as 'Magsaysay for President'. Lansdale's Airforce biography makes no mention of the CIA.

- ↑ John Ranelagh, The Agency: The Rise and Decline of the CIA (New York Simon and Schuster, 1987), see page 226

- ↑ http://www.ratical.org/ratville/JFK/USO/appC.html see also http://cryptome.org/ic-black4701.htm

- ↑ Eric Pace, ‘Edward Lansdale at 79; Advisor on guerrilla warfare’, New York Times, 24 February 1987

- ↑ Eric Pace, ‘Edward Lansdale at 79; Advisor on guerrilla warfare’, New York Times, 24 February 1987

- ↑ Edward Lansdale's (1962)"Operation Mongoose: Program Review by the Chief of Operations," prepared for the U.S., Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States 1961-1963, Volume X Cuba, 1961-1962).

- ↑ John Ranelagh (1987)'The Agency', see page 386.

- ↑ http://www.espionageinfo.com/Nt-Pa/Operation-Mongoose.html

- ↑ http://www.themilitant.com/2002/6637/663750.html

- ↑ Jonathan Nashel. Edward Lansdale's Cold War. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005. Reviewed by Charles J. Pellegrin on H-War, H-Net Reviews, December 2006

- ↑ http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/COLDlansdale.htm

- ↑ http://www.counterpunch.org/valentine03082003.html

- ↑ http://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/1996/analysis/back.time/9606/28/index.shtml