Difference between revisions of "Special Branch Registry"

Peter Salmon (talk | contribs) (Created page with "{{Police_Unit_sidebar_(URG)|Series=Domestic Extremism |Name=Special Branch Registry |Alias=Special Branch Records, IMOS |Parents=Metropolitan Police Special Branch |SubUni...") |

Peter Salmon (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

In the late 1970s and the 1980s, computerisation of Special Branch began, including of the records sections (see further below).<ref name="pocock.6-4-17"/><ref name="wilson.adams"/> Within the Metropolitan Police Special Branch a number of systems were introduced which evolve over time. Not all the historical records were converted, though indices were made electronic to permit searching. | In the late 1970s and the 1980s, computerisation of Special Branch began, including of the records sections (see further below).<ref name="pocock.6-4-17"/><ref name="wilson.adams"/> Within the Metropolitan Police Special Branch a number of systems were introduced which evolve over time. Not all the historical records were converted, though indices were made electronic to permit searching. | ||

| − | A 2003 HM Inspectorate of Constabulary report critical of Special Branch IT systems generally resulted in the introduction of a common software systems, in particular the [[National Special Branch Information System]] which took over many of the previous functions.<ref>In early 2003, the HM Inspectorate of Constabulary found that, across forces, 'Special Branch lacks adequate IT overall, a Special Branch national IT network would significantly enhance effectiveness.' The report also called on the Home Office to identify national Special Branch IT requirements and to implement a robust strategy. See: In brief, ''Computer Weekly'', 30 January 2003 (accessed via Nexis).</ref> It was not fully adopted within the Metropolitan Police until 2011.<ref name="pocock.6-4-17"/> and has since been replaced by the [[National Intelligence | + | A 2003 HM Inspectorate of Constabulary report critical of Special Branch IT systems generally resulted in the introduction of a common software systems, in particular the [[National Special Branch Information System]] which took over many of the previous functions.<ref>In early 2003, the HM Inspectorate of Constabulary found that, across forces, 'Special Branch lacks adequate IT overall, a Special Branch national IT network would significantly enhance effectiveness.' The report also called on the Home Office to identify national Special Branch IT requirements and to implement a robust strategy. See: In brief, ''Computer Weekly'', 30 January 2003 (accessed via Nexis).</ref> It was not fully adopted within the Metropolitan Police until 2011.<ref name="pocock.6-4-17"/> and has since been replaced by the [[National Common Intelligence Application]]. |

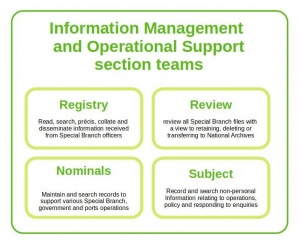

In the same period, the organisation itself underwent various changes. 2004 saw IMOS re-organised, with Computer and Registry Sections merged, and the collecting of material was re-arranged into the thematic sections:<ref name="pocock.6-4-17"/> | In the same period, the organisation itself underwent various changes. 2004 saw IMOS re-organised, with Computer and Registry Sections merged, and the collecting of material was re-arranged into the thematic sections:<ref name="pocock.6-4-17"/> | ||

Latest revision as of 16:56, 29 June 2020

This article is part of the Undercover Research Portal at PowerBase - investigating corporate and police spying on activists.

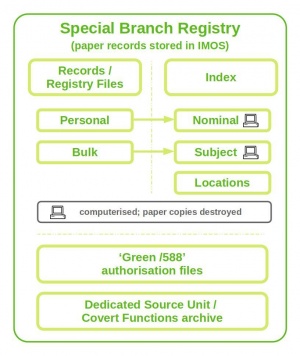

The Special Branch Registry is a filing system used by the Metropolitan Police. Since 2004 it has been referred to as the Intelligence Management and Operation Support. Though its existence is well established, little detail regarding it is in the public domain. The Registry is of particular importance as it is where files on political activists and other persons of interest to Special Branch were kept in what are known as 'Registry Files'. These were organised by both group and individuals, containing a history of their activity as recorded by Special Branch officers, including undercover police.

According to one source:[1]

- IMOS remit was and remains to record and administer intelligence received from all areas of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch (MPSB).

Registry (or Records) refers to the files themselves, while IMOS was the wider administrative body within MPSB, which looked after them and related issues.[2] It is separate to the wider General Registry held by the Metropolitan Police prior to computerisation of the police. However, following re-organisations, the term IMOS is now used to refer to the legacy paper files and the indices used to access them, rather than the unit itself.

This article deals with Special Branch databases up to the mid 2000s and their subsequent incorporation as legacy records in later databases. Some source material has been collated in the page Special Branch Registry: source material. For related topics see:

- National Special Branch Information System (NSBIS)

- National Domestic Extremism Database

- National Common Intelligence Application (NCIA)

- Animal Rights National Index (ARNI)

Contents

Source of material in Registry Files

The material in the files came from a variety of sources, including reports from undercovers from the Special Demonstration Squad,[3] albeit sanitised as to its origins.[4] According to the book Undercover:[5]

- Much of the intelligence in these files was generated from publicly available information. For example, desk officers scoured press clippings, noting down names of activists quoted in articles or recording the names of people who had signed petitions. When the homes of activists were raided, branch officers would comb through the contents of address books, letters and cheque-stubs to work out whom they were in contact with. Moving up the scale, phones were tapped and mail was opened. This was the routine, systematic work of the branch.

The book also noted:

- The files on individuals would contain reports of their activities at protests, other more general intelligence and information from sources such as newspapers articles. It would include, for instance, where they lived, where they worked, and whom they were friendly with in the campaign. [SDS undercover officer Peter Francis] himself opened up new files on around 25 campaigners he believed needed to be monitored.

- Each file on an individual required an up-to-date photograph and Special Branch had an uncanny ability to acquire photographs when it needed them. Official images were available to the squad - from driving licences, passports and suspect mugshots taken inside police stations. Upon request, Special Branch could also deploy sniper-like photographers with long lenses.

Whistleblower Peter Francis explained to the authors of Blacklisted how he opened a file on a specific political campaigner while undercover for the Special Demonstration Squad:[6]

- The file was created some time around 1995. [...] So I opened what we call an RF – a registry file. Then, every time I saw him on a demo or I had a drink with him, that would go on the file. 'Seen as politically dangerous' is the assessment I would have had of him. In order for me to create a file on him I need to say something like that because he was regarded as being a subversive.

History

It is uncertain when the Registry was founded. One 2014 Metropolitan Police document noted that in 1923, the Special Branch Registry was absorbed into the General Registry maintained by the Metropolitan Police, but that it had recovered its independent status in 1940.[7] However, the Special Branch Registry is also apparently subject to criticism in a 1929 Memorandum by the then Head of MI5, Hugh Sinclair.[8] This implies that even though merged into the General Registry, it maintained its own identity.

Det. Insp. Alistair Pocock, in a statement to the Undercover Policing Inquiry focusing on records storage in Special Branch, could only assert that it definitely existed since the 1960s and probably prior to that.[1]

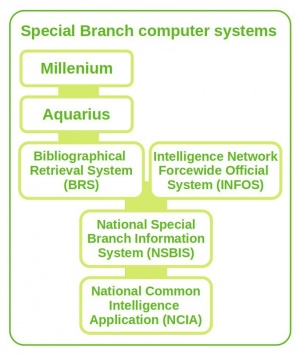

In the late 1970s and the 1980s, computerisation of Special Branch began, including of the records sections (see further below).[1][9] Within the Metropolitan Police Special Branch a number of systems were introduced which evolve over time. Not all the historical records were converted, though indices were made electronic to permit searching.

A 2003 HM Inspectorate of Constabulary report critical of Special Branch IT systems generally resulted in the introduction of a common software systems, in particular the National Special Branch Information System which took over many of the previous functions.[10] It was not fully adopted within the Metropolitan Police until 2011.[1] and has since been replaced by the National Common Intelligence Application.

In the same period, the organisation itself underwent various changes. 2004 saw IMOS re-organised, with Computer and Registry Sections merged, and the collecting of material was re-arranged into the thematic sections:[1]

- Operations

- International

- Irish

- Domestic Extremism

While in 2006, Metropolitan Police Special Branch (also known as SO12) was merged with Anti-Terrorist Branch (SO13) to form SO15 / Counter Terrorism Command. The latter continues to hold the old Metropolitan Police Special Branch Registry and legacy computer records.[1][11]

Structure of paper records

Until late 2011, the Registry / IMOS received all material in hard copy, with Registry Section being responsible for maintaining manual indices of the material.[1]

Personal & Bulk files

A 'Personal file' refers to the MPSB file held on a particular individual, and catalogued in the Nominal Index. When the decision was taken to open a file on an individual, the white card from the Nominal Index was used as the initial basis, being 'converted into a history sheet which was then stored at the rear of the new Personal file. The history sheet was used to record further information concerning the individual's activity.'[1]

The 'Bulk files' are non-personal files, including specific files relating to groups, and were catalogued in the Subject Index. As with personal files, the original white subject index card was used to start the bulk file, being converted into a similar history sheet.[1]

Neither the Personal or Bulk files have been computerised, and remain available in hard copy. They can be located through searches in indices accessible through the IMOS computer systems such as BRS / SO15 NSBIS (see below). Some of the files have been destroyed in accordance with MPS information management policies and the law; no comprehensive record of what was destroyed was kept.[1]

The hard copy files are stored at IMOS and in a Metropolitan Police deep storage facility, which can be retrieved at the request of IMOS staff.[1]

Indices

Before computers were available, the Registry was a large number of paper records, organised into files and accessed through a number of indexes.

- Nominal index

- According to Pocock, this:[1]

- consisted of binders containing white card slips that noted the biographical data of individuals (for example, their names and aliases) and a summary of their known activity. The slips were cross-referenced with relevant file numbers (known as 'mentions'). The slips were an aid to finding the files in which an individual was referred to.

- Once a file was opened on an individual, the white slip was replaced by a pink one 'containing the individual's biographical data and personal file number'.

- These were initially computerised on the Millennium System, and from 2003 on the BRS, with the hard copy version being destroyed.[1] Also of 2003, any new additions to the Nominal Index were recorded directly on the BRS - now accessible through SO15 NSBIS.[1]

- Subject Index

- This was a card index which contained 'amongst other matters, dedicated sections relating to entities (such as groups), policy, operations, events and a large miscellaneous section'. It was made up of white cards that held 'a summary of the information contained in the reports' and were 'cross-referenced with relevant file numbers'.[1]

- Their main purpose was to assist finding the original reports sorted in the Registry. When a bulk file (see below) was opened, the white card was replaced with a pink one detailing the bulk files created relating to that subject. When computerisation took place, the pink cards were added to the electronic database, but the white cards in the index destroyed.[1]

- In 2004 it was described as:[2]

- The subject index contains details of organisations, firms, terrorist incidents, demonstrations and events to name just a few subject areas. Team members also record non-personal information relating to operations, policy and various enquiries on behalf of SO12, other police forces and government agencies. ... Over the last two years the section has run an intensive weeding, revision and destruction programme in preparation for conversion from a manual to a computerised system.

- Locations Index

- Pocock noted:[1]

- Each registered hard copy file had a corresponding location slip bearing the file number and title. This was used to book out files to sections or individuals and acted as an audit trail.

- The Locations Index has not been computerised, and as of 2017 is located in the IMOS file store where it is used to search for historical paper copies of Personal and Bulk files.[1]

Management of paper files

According to Pocock:[1]

- When a document was received into IMOS, it would be allocated to the most appropriate file by IMOS records staff. Once the document was assigned to a file, it would be indexed with a file number and folio (or page number). A summary of the information in the document would be made to assist its retrieval on request.

- The document would also be cross-referenced with nominal and non-personal matters. SB Registry staff would index the nominals on the Nominal Index and the Subject Index staff would note the document for its subject matter on the Subject Index.

Computerisation

According to Special Branch officers Ray Wilson and Ian Adams, computerisation started under Deputy Assistant Comissioner Rob Bryan[12] in the late 1970s:[9]

- A time consuming process of back-record conversion was undertaken as part of the computerisation of all the [Scotland] Yard's specialist records. When completed, the new system permitted instant access on visual display units installed in SB offices at the Yard and at Heathrow Airport to all the Branch's records, formerly stored on bulky files and accessed through equally bulky card indices. Appropriate security measures were installed to ensure that only suitably vetted personnel could access the more sensitive records.

- [...] Special Branch Registry was now a highly professional, integral section of MPSB, run by a senior executive officer and staffed by civilians, predominantly female, who were all positively vetted and had their own career structure.

Pocock, however, places the start of computerisation in the 1980s, with the founding of the Computer Section within IMOS, noting:[1]

- the gradual shift to electronic records began with the introduction of the Intelligence Network Force wide Official System ('INFOS'). Initially, storage on the INFOS system was limited and only the top 300 nominal records of interest were computerised.

While INFOS was managed by the IMOS Computer Section, the Registry Section had its own system - Millennium, on which the Nominal Index was placed. Millennium was, in turn, replaced by the Aquarius System.[1]

At some point, INFOS was merged into Aquarius and named the Bibliographical Retrieval System ('BRS'). In 2003, the old hard copy Nominal Index was computerised on the BRS, and any new entries on the Index were stored on it rather than in paper form. Of the Subject Index, only the pink cards part (found at the back of the Bulk files) were computerised - the white cards in the index were destroyed.

Also, in early 2003, the HM Inspectorate of Constabulary found that, across forces, 'Special Branch lacks adequate IT overall, a Special Branch national IT network would significantly enhance effectiveness.' The report also called on the Home Office to identify national Special Branch IT requirements and to implement a robust strategy.[13] This lead to the creation of the National Special Branch Intelligence System.

A 2004 history of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch implies that the Nominal and Subject Indices had their own teams which managed their own sets of records. Other teams included the general management of information received by IMOS, and a section whose responsibility was to review all files created within Special Branch, including the Registry, with a review to retaining, archiving or destroying them. For a full description of the different team activities see IMOS activties in source material).[2]

A 2015 briefing from SO15 noted the IMOS computerised indexing system had grown to approximately 80,000 records.[14]

Pocock explained that the information on the IMOS computer systems was collated from a wide variety of sources:[1]

- Material received by IMOS consists of intelligence reports and enquiries on the strategic intelligence priorities that SO15 collects upon, messages from the MPS Computer Aided Despatch system (force wide computer system), correspondence from other police forces and partner agencies; information and intelligence generated from operational activity; local and relevant MPS guidelines policy; open source material.

In 2011, SO15 (into which MPSB had been merged) switched over to the National Special Branch Information System (NSBIS). With NSBIS, SO15 moved entirely to electronic record keeping, though it kept paper-files that existed prior to this. The BRS indices were made accessible through SO15 NSBIS to facilitate searching for and retrieving the paper records created within IMOS prior to computerisation.[1]

INFOS

Like NSBIS, INFOS was information management software, which seems to have also been used elsewhere in the police for operations that needed to be kept secure. One statement to the Undercover Policing Inquiry notes that:[11]

- INFOS - This IT system is used for a range of purposes in relation to covert policing including records of undercover deployments. It contains records of Advanced level operations since 1999, Foundation level operations since 2007 and Covert Internet Investigator operations since 2008. This system is only accessible to a small number of vetted personnel.

In 1994, the system was used throughout the Metropolitan Police according to an internal report on corruption, which noted corrupt officers were accessing it on behalf of criminals.[15][16]

The particular instance of INFOS referred to in that report was, in 2016, managed by SC&O35, the Metropolitan Police's Covert Intelligence unit[17]

File storage and access

By 2017, the hard copy Personal and Bulk files were kept in an IMOS file store and in a Metropolitan Police deep storage facility - which can be retrieved at the request of IMOS staff. The Location Index is also kept in the IMOS file store.[1] This file store is in a secure London location to permit ease of access in relation to various public inquiries including the Undercover Policing Inquiry and the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse.[11]

As of June 2015, there were 5,449 IMOS 'Secret and Confidential' files stored in hard copy in 193 boxes at the Metropolitan Police deep storage facility managed by logistics company TNT, relating to the whole of SO15 activity (including Special Branch legacy files). In January 2015, thirty boxes were returned to the MPS for review, at a cost of £3,750 each way.[14]

Only security vetted individuals with appropriate security clearance within SO15 have access to the IMOS file store. During working hours this is supervised by IMOS staff. Outside of working hours, the store is locked with only staff from the SO15 Reserve Room having access to it - these are the only personnel beside IMOS staff with a key to the store.[1][18]

According to Pocock:[1]

- Current practice determines that a member of IMOS staff will locate and draw the files, book them out and hand them to the requester who should not enter the store unless accompanied by an IMOS staff member. This system protects the integrity of IMOS records and ensures that a security vetted S015 officer is accountable for any files booked out. Similarly, staff from Operation Herne and the Assistant Commissioner's Public Inquiry Team (AC-PIT) that require access to IMOS files are subject to the same process. Access to IMOS files is on a 'need to know' basis, therefore, with the exception of those officers and staff responding to this Inquiry, non-S015 staff will have no need to access IMOS files. No specific reason is required to book out an IMOS file. Booked-out files are subject to periodic reminders for return.

Undercover policing scandal

The Personal files are considered of relevance in issues around the Undercover Policing Inquiry. Non-state/police core participants in the Inquiry have made access to their Personal files a central demand. As of 2020 this had not happened.[19][20][21]

Pocock, however, told the Undercover Policing Inquiry:[1]

- First, it is important to note that generally the source of intelligence was not recorded on intelligence submitted to IMOS for indexing. Intelligence product was 'sanitised' by the office submitting the intelligence to remove the details of the source. Intelligence received by IMOS could have originated from a significant number of sources, most of which are unrelated to undercover policing. IMOS does not hold an index of intelligence received from a particular source (such as a specific undercover officer), from a specific unit (such as the SDS) or by certain means (such as undercover policing).

- Personal and Bulk files must be manually searched to attempt to identify intelligence that may have originated from a specific undercover officer, a specific unit and/or undercover policing. The PILT have learned that there are some indicators which may suggest that intelligence originated from an undercover officer or SDS, but the correct attribution of intelligence requires a very careful examination of the records and even then it is not guaranteed.

Plans to put the IMOS archive into deep storage completely were shelved in light of the Undercover Policing Inquiry and related investigations.[22]

The Metropolitan Police's own investigation into the undercover policing scandal, Operation Herne, made a number of scathing criticisms of Special Branch collection of information, including:[23]

- It is quite clear that maintaining the secrecy of the unit and protecting the identity of the officers was of paramount importance to all involved and in being so focused on this aspect the management of the SDS, of the MPS Special Branch and ultimately the MPS Executive Leadership of the day collectively failed. They failed in respect of keeping abreast of changes in practice and legislation, in considering the clear risks of collateral intrusion by the “hoovering” covert collection methodology, and in failing to effectively weed “community gossip” that appears to have limited operational value as it was rarely, if ever, disseminated to the wider MPS organisation. They failed in their not embracing and using the available national undercover training course which would have ensured that the operatives and supervisors better understood their personal responsibilities and the concept of collateral intrusion, necessity and proportionality. They failed in not working strictly to RIPA which would have ensured that authorising officers would have set clear objectives for the covert deployments and the collection of only appropriate and relevant intelligence. They failed in not applying MOPI which would have led to a proper assessment of relevance and the weeding of unnecessarily retained irrelevant personal information.

- Ultimately the Metropolitan Police Service failed in not working to the nationally accepted Home Office Guidelines on the workings of Special Branch – had they done so this activity may well not have taken place, the intelligence would not have been recorded and if it had been it would have been rapidly weeded as it did not relate either directly or indirectly to the discharge of Special Branch functions.

More detail on this can be found in the Special Branch Registry: source material page.

Other material

Dedicated Source Unit

A SO15 Briefing for SO15 / Counter Terrorism Command makes note of another Special Branch unit which had its own related files:[14]

- Dedicated Source Unit / Covert Functions Archive

- This contains approximately [redacted] physical files relating to CHIS activity by SO15 and SO12 dating from the 1970's to present day. Although some of the files are indexed in a protected manner on SKY, it is only the subject's name that was indexed. Details tasking, other bio details, intelligence generated (although disseminated at the time) is not searchable within that physical data. A succession of decisions about the deletion of CHIS records have been made by the National Source Working Group and MPS Directors of Intelligence / Covert Policing. The current position is that CHIS records are rarely deleted. A project was initiated to identify a means of making this archive more searchable, no solution has yet been identified and there is no current RRD activity taking place.

'Red Docket' Files

In 2015, The Sun reported that Special Branch held files in which police had recorded celebrities and politicians engaging in compromising behaviour. These included photographs apparently taken by undercover police during Operation Circus, a 1984/1985 Metropolitan Police investigation targeting rent boys in and around Piccadilly Circus.[24] The newspaper reported:[25]

- Sources told The Sun that 'red docket' files — named after their covers’ colour — were placed in a Special Branch registry but have now vanished.

- Analysis of audit trails is being carried out on child abuse case files booked out by officers.

- Special Branch is under investigation over allegations of nobbling inquiries which would have exposed figures including MP Cyril Smith.

No material has been discovered which corroborates this story.

Relation to the MI5 Registry

The Registry is not to be confused with a similar one maintained by MI5.[26] Various sourcs mention MI5 asking Special Branch to search their Registry Files for material regarding particular individuals. Know examples of individuals subject to such requests are the WWII German spy Josef Jakobs[27] and in 1961, society osteopath Stephen Ward during the Profumo Affair. Though Special Branch reported that nothing to Ward's discredit was known to them, MI5 requested to be kept informed and by April 1962 they had passed to MI5 various reports of Ward's apparent sympathy to communism.[28]

That material gathered by Special Branch would find its way into MI5 Registry Files is also noted by former MI5 employee Cathy Massiter in a 1985 newspaper interview, See explained that MI5's file on MP Joan Ruddock, then head of CND, included 'Special Branch references to her movements'.[29] Much later, former Special Branch undercover Peter Francis said he contributed to Ruddock's Special Branch file in the 1990s, and to the files of a number of other MPs, including Peter Hain.[30]

Massiters claims were confirmed in the 2002 BBC series True Spies', which noted:[31]

- Commentary: Ricky Tomlinson's file was only one of hundreds of thousands that Special Branch compiled on suspected subversives. Each file was copied to M15 - the Security Service.

- Tony Robinson (Lancashire Special Branch): When I first joined Special Branch I went on a preliminary course down at the headquarters of MI5, and we were briefly taken down to what was called 'the Registry', which was where the files were kept, just these thousands and thousands of thousands of files in the racks there must have been upwards, if not more, than a million.

Peter Hain, the leading Anti-Apartheid campaigner and former Labour Government Minister, wrote an opinion piece for The Guardian about being named in both MI5 and Special Branch files along with fellow MPs: [32]

- Following media revelations about old MI5 files held on Labour government ministers, the head of MI5, Sir Stephen Lander, came to see me at the Foreign Office in 2001 when I was Europe minister. Low key and courteous, he confirmed there had indeed been such an MI5 file on me and that I had been under regular surveillance. However, he was at pains to say, I had nothing to worry about because the file had long been “destroyed” when I had ceased “to be of interest”. Furthermore, [...] He made no mention of what appears to have been an entirely separate tranche of files compiled by Special Branch on me and a group of similarly democratically elected, serving MPs.

- That Special Branch had a file on me dating back 40 years ago to Anti-Apartheid Movement and Anti-Nazi League activist days is hardly revelatory. That these files were still active for at least 10 years while I was an MP certainly is and raises fundamental questions about parliamentary sovereignty. The same is true of my Labour MP colleagues Jack Straw, Harriet Harman, Jeremy Corbyn, Diane Abbott, Ken Livingstone, Dennis Skinner and Joan Ruddock, as well as former colleagues Tony Benn and Bernie Grant – all of us named by Peter Francis, a former Special Demonstration Squad undercover police spy turned whistleblower.

- But Peter Francis states that he inspected our files during the period from 1990 when he joined Special Branch to when he left the police in 2001 – exactly when we were all MPs. Jack Straw was a serving home secretary from 1997, and I was a foreign office minister from 1999, both of us ironically seeing MI5 or MI6 and GCHQ intelligence almost daily to carry out our duties.

Notes

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 Det. Insp. Alistair Pocock, Witness statement, Metropolitan Police Service, 6 April 2017, incorporating statement of 3 January 2017 (accessed via Undercover Policing Inquiry - ucpi.org.uk).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 History of UK Special Branch, Metropolitan Police, August 2004 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).

- ↑ Rob Evans & Rowena Mason, Police continued spying on Labour activists after their election as MPs, The Guardian, 25 March 2015 (accessed 2 June 2020).

- ↑ Undercover Policing Inquiry: Two Year Update, July 2017 (accessed 7 July 2020).

- ↑ Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain's Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013.

- ↑ Dave Smith & Phil Chamberlain, Blacklisted: The Secret War between Big Business and Union Activists , New Internationalist, 2015.

- ↑ In 1923 the Special Branch registry, which had hitherto been independent from other record-keeping systems, was absorbed into the central registry (General Registry) of the Metropolitan Police. This was however largely in order to facilitate staffing levels and its work remained independent from other types of registration. In 1940 the General Registry was re-organised and since that time the MPS SB has maintained an independent registry.

Quoted in a decision notice of the Information Commissioner's Office, 5 February 2015, relating to the Metropolitan Police opposing of release of Special Branch files for national security reasons. - ↑ This apparent memorandum was critical in general of Special Branch, including the Registry and SB Press Room. See Memorandum of Hugh Sinclair, dated 30 April 1929, and sent to Foreign Office on 7 May 1929, cited in Gill Bennett, Churchill's Man of Mystery: Desmond Morton and the World of Intelligence, Routledge, 2006

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ray Wilson & Ian Adams, Special Branch: A History 1883-2006, BiteBack Publications, 2006.

- ↑ In early 2003, the HM Inspectorate of Constabulary found that, across forces, 'Special Branch lacks adequate IT overall, a Special Branch national IT network would significantly enhance effectiveness.' The report also called on the Home Office to identify national Special Branch IT requirements and to implement a robust strategy. See: In brief, Computer Weekly, 30 January 2003 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Det. Supt. Neil Hutchison, Witness Statement to Undercover Policing Inquiry, Metropolitan Police, 17 June 2016 (accessed via ucpi.org.uk).

- ↑ Robert P Bryan, was Deputy Assistant Commissioner who headed Special Branch 1977 to 1981.

- ↑ In brief, Computer Weekly, 30 January 2003 (accessed via Nexis).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Appendix A to SO15 report dated 11th June 2015 concerning Information Risks in SO15. Appears in Exhibit D754: Debriefing re Management of Information within SO15, Metropolitan Police, June 2015, (accessed via ucpi.org.uk, appended to a witness statement of Det. Supt. Neil Huchison).

- ↑ Peter Jukes & Alistair Morgan, Who Killed Daniel Morgan? Britain's most investigated murder, Bonnier Books, 2017.

- ↑ Other sources note earlier dates such as 1992. See Bill Hebenton, Policing Europe: Co-operation, Conflict and Control, Macmillan International, 1992.

- ↑ See, for example, FOIA Request answer: Total overtime hours worked by MPS officers from 2014/15 to 2017/18, Metropolitan Police, 1 December 2018 (accessed 6 June 2020).

- ↑ Det. Supt. Neil Hutchison, Witness Statement to Undercover Policing Inquiry, Metropolitan Police, 9 June 2016 (accessed via ucpi.org.uk).

- ↑ Disclosure, Police Spies Out Of Lives, undated (accessed 15 June 2020).

- ↑ Scotland Yard demo – Stop the Shredding, Release the Files, Campaign Opposing Police Surveillance, 15 January 2016 (accessed 15 June 2020).

- ↑ Frances Perraudin, Labour MPs spied on by police demand to see secret files held on them , The Guardian, 26 March 2015 (accessed 15 June 2020).

- ↑ Neil Hutchison, Email of 1 October 2015: IASB Actions, Metropolitan Police (accessed through ucpi.org.uk where it appears as exhibit D753, to a statement of Neil Hutchison).

- ↑ Mick Creedon / Operation Herne, Report 3 - Special Demonstration Squad: Mentions of Sensitive Campaigns, Metropolitan Police, July 2014.

- ↑ Det. Sgt. Maggie Samuels, Closing Report - Operation Jordana (Op Winter Key Professional Standards Team Investigation], Metropolitan Police, 17 February 2017 (accessed via iisca.org.uk).

- ↑ Mike Sullivan, VIP paedo cover-up, TheSun.co.uk, 18 September 2015 (accessed 3 June 2020).

- ↑ Christopher Andrew, Defence of the Realm: the authorised history of M15, Penguin, 2012.

- ↑ Arthur O. Bauer, KV 2/27 - Prosecution of Jacobs Josef, cdvantext2.org (accessed 7 June 2020).

- ↑ Rupert Allason, The Branch: A History of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 1883-1983, Secker & Warburg, 1983.

- ↑ Nick Davies, MI5 whistleblower exposes ‘illegal’ spying on peace movement, The Observer, 24 February 1985 (accessed via NickDavies.net).

- ↑ Rob Evans & Rowena Mason, Police continued spying on Labour activists after their election as MPs, The Guardian, 25 March 2015 (accessed 10 June 2020).

- ↑ True Spies - Episode 1: Subverting the subversives, BBC Two, 27 October 2002; transcripts.

- ↑ Peter Hain, Why where Special Branch watching me even when I was an MP?, The Guardian, 25 March 2015 (accessed 15 June 2020).