National Police Coordination Centre (NPoCC)

The National Police Coordination Centre (NPoCC) is a national unit, which coordinates the local, regional and national police response to range of events including public order incidents. It was formed in April 2013 as part of the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC).[1]

Contents

History and Remit

- The NPoCC works with all forces across England and Wales as well as Police Scotland, Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) and non-home office forces including Jersey, Guernsey, Isle of Man, Civil Nuclear Constabulary and other national police units to undertake a rolling programme of capacity assessments for a wide range of specialist police skills.[2]

Like the NPCC, the NPoCC is hosted by the Metropolitan Police Service, but reports to the NPCC.[2]

Specifically its functions are:[2]

- 6.1.1 To support the operational co-ordination of national operations including informing, monitoring and testing force contributions to the Strategic Policing Requirement working with the National Crime Agency where appropriate

- 6.1.2 To support the operational co-ordination of the national police response to national emergencies and the co-ordination of the mobilisation of resources across force borders and internationally

- 6.1.3 Coordinate the Police Service response and provide representation during COBR (Cabinet Office Briefing Room)

- 6.1.4 The co-ordination of the national police response to UK disaster victim identification

- 6.1.5 The continual assessment of national capacity and capability in relation to the Strategic and National Policing Requirements and maintaining information and data sets relating to policing specialist skills and assets for the benefit of the police service

- 6.1.6 To co-ordinate a continuous testing and exercising regime to ensure effective mobilisation of national assets in a crisis

- 6.1.7 Developing reporting mechanisms with the Home Office and central government crisis management

Background

In August 2011, widespread riots took place across England, triggered by the police killing of Tottenham resident Mark Duggan.[3] The considerable property damage led to the police’s response to the disorder being widely criticised from a variety of standpoints.[4][5][6]

A 2011 HM Inspectorate of Constabulary report into the policing response focused on the technical-response issues and found that the Police National Information Coordination Centre (PNICC) was not up to the job - being 'reactive' rather 'proactive' and that its response was patchy due to the under-utilisation of its information and resources.[7]

The NPoCC replaced the PNICC on 13 April 2013 and was originally directly funded by the Home Office.[1] A media release issued on the NPoCC's first anniversary in April 2014, said:

- Commissioned by the Home Office and led by Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO), NPoCC replaced the Police National Information Centre (PNICC) and was created with a wider remit to ensure policing is better prepared for wide scale disorder like the riots of 2011.[8][9]

On launch, it was stated:

- NPoCC will be a lot more proactive than PNICC, which previously focused either on pre-planned events, or when activated in response to a spontaneous emergency.

- NPoCC will be a lot more proactive than PNICC, which previously focused either on pre-planned events, or when activated in response to a spontaneous emergency.

- NPoCC will carry out the same duties, but also focus on:[1]

- NPoCC will carry out the same duties, but also focus on:[1]

• Monitoring which specialisms are available nationally in each police force such as firearms, public order officers, search officers, mounted officers, and dog handlers, among others.

• Establishing a test and exercise regime to ensure effective mobilisation of national assets in a crisis

• Dealing with significant event planning

• Working closely with the National Domestic Extremism Unit to monitor intelligence and effectively prepare for potential threats.

Originally, it was formed under the auspices of the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) but when that body was scrapped, it fell under its successor organisation the National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC).[2]

The NPoCC reports to the NPCC and is monitored by an eponymously named governance board.[2] It should be noted that while the NPoCC is the lead police agency in many types of major incidents, it does not have that role in cases deemed to be connected with terrorism - this falls to the Counter Terrorism Policing Operations Centre (CTPOC) operationally, and the UK National Counter Terrorism Policing Headquarters (NCTP HQ) in developing policy.[10][11] The NPoCC, however, does assist with asset management and audit for counter terror (and organised crime) purposes.[12] There is also quite some overlap between the NCTPHQ remit that includes 'domestic extremism' and public order incidents falling under the NPoCC's remit.

In 2017, a budget was planned for employing the following senior ranks of police officers within the NPoCC: 1 Assistant Chief Constable, 1 Chief Superintendent, 1 Superintendent and 2 Inspectors.[13]

Levels of Activation: Police 'Mutual Aid'

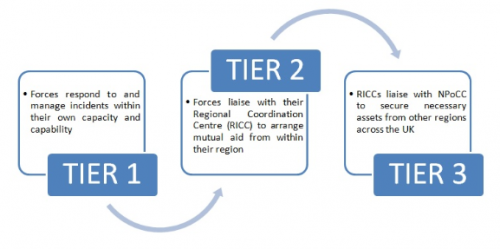

Depending on the scale and seriousness of a 'major incidents', the role of the NPoCC would vary. They use a three stage ('tier') schemata.[14]

Tier 1 - Local. The local force will deal with the event itself and will make use of its own resources. 'An assessment of whether resources will be needed from outside the force area - and whether assets are available regionally through the Regional Information and Coordination Centres (RICCs) or nationally through the NPoCC will be a matter for assessment by senior officers from all those police bodies'.[15]

Tier 2 - Regional. 'The coordinating organisation will one of the nine nine RICCs'. The NPoCC's role will be to assess whether the ('mutual aid') resources needed are available at regional level, or if the request need to be escalated to a national level.[15]

Tier 3 – National. NPoCC is responsible for mobilisation at a national level. It: 'assesses national capacity and contribution in relation to the Strategic Policing Requirement and National Policing Requirement establishes and coordinates continuous testing and exercising regimes to ensure effective capability and mobilisation of national assets when required facilitates mutual aid in and provides a coordination facility in times of crisis ensures effective reporting mechanisms with the Home Office and central government crisis management structures'.

It also takes the lead in cases where mass fatalities occur.[15]

The NPoCC works with other national coordination centres which have responsibility for mobilising specialist resources for example, the Counter Terrorism Coordination Centre (CTCC) and the Police National Chemical Biological Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) Centre.[14]

Mercury System

The Mercury Computer System is used by the NPoCC, local police forces and NCTPHQ. It 'assists in managing the mutual aid deployment of police resources across force geographic boundaries', as well as identifying the number of 'specialisms' available within each force.[16][17][12]

NPoCC in Action

2013 G8 Meeting, Fermanagh

The launch of the NPoCC mentioned that the meeting of the G8, hosted by the UK and taking place at Lough Erne golf resort in Fermanagh in on 17 and 18 June 2013 would be 'the biggest police operation in Northern Ireland's history, involving 8,000 officers, 4,400 of them local and 3,600 from England and Wales.' [18] There was no counter mobilisation on the scale that either the 'Dissent! Network' or 'G8 Alternatives' launched when the G8 visited Scotland in 2005.[19][20] Counter-Terror Command and the Security Services would have been responsible for public order or terrorist threat, none of which materialised during the conference. Nevertheless, the NPCC stated that in 2013 the 'NPoCC supported the G8 summit in Northern Ireland, assisted PSNI in dealing with wide scale riots during the marching season.'[21]

Anti-Fracking Protests

Within the UK, protests against fracking (high pressure drilling for shale gas) started in 2011.[22] The controversial and environmentally damaging extractive industry had previously met with significant resistance in the USA and Canada.[23] The anti-fracking protests was the first significant mobilisation[24] in the UK social and environmental movement after the revelation that a significant and long-term deployment of undercover police officers had been tasked to spy upon political activists. Groups that had been targeted in the recent past were now part of the anti-fracking movement. Aggressive public order policing, another noticeable part of the police's response to environmental protests, continued if not intensified during fracking protests.[25][26] A College of Policing public order training exercise conducted in 2014 used a fictional fracking protest by way of exercise.[27]

The NPoCC coordinated police 'mutual aid' requests to anti-fracking protests in 2013/14 in Balcombe, Sussex and later in 2017 at the Cuadrilla site in Lancashire.[21][28] However, several official police documents have suggested that the lead agency would have been the NCTHQ, as the protests and protesters were classified as 'domestic extremist' with some individuals even referred to the UK government's controversial PREVENT counter-terrorist programme.[29]

President Trump's visit to UK

The NPoCC were also involved in organising 'mutual aid' for US President's Trump's visit to London in July 2018.[30] As with other large scale events, officers across the UK were mobilised at the cost of £14m.[31] Some senior officers apparently questioned the necessity of using 4000 officers for the visit, admist concern that it would put pressure on local policing resources.[31]

Preparing for Brexit

A September 2018 article in The Sunday Times made a number of claims about police preparations for a 'no-deal Brexit' based on a secret report written by the NPoCC:[32]

- Police chiefs are drawing up contingency plans to deal with widespread civil disorder at the country’s borders and ports in the event of a no-deal Brexit, according to a leaked report. The bombshell document, prepared by the National Police Co-ordination Centre, warns that the 'necessity to call on military assistance is a real possibility' in the weeks around Britain’s departure from the EU. The report, which is due to be discussed at a meeting of the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) next week, claims that “widespread leave embargoes” will be required. Some forces, such as Kent, are expected unilaterally to cancel rest days and leave immediately after March 29. The document also warns that a no-deal Brexit could lead to a rise in crime, particularly theft and robbery, as Britain suffers food and drug shortages with the 'expectation that more people will become ill'.[32]

It also said 'that the ability of forces to plan for a no-deal Brexit is being 'undermined by a perceived lack of communication between the policing unit of the Home Office and the Department for Exiting the European Union'.[32]

It warns that the main concern for the police is that food and goods shortages, including medical supplies, will result in 'widespread unrest'. The disruption and civil unrest could last for three months either side of March 29 — rather than the six weeks being planned for by the government. The core function of the NPoCC, the coordination of mutual aid is highlighted, the introduction of which would have a 'serious knock-on effect on day-to-day policing'.[32] In response, NPCC coordinator for Brexit and Chief Constable of Hertfordshire[33] Charlie Hall, said: 'The police are planning for all scenarios that may require a police response in the event of a no-deal Brexit. At this stage, we have no intelligence to suggest there will be an increase in crime or disorder. However, we remain vigilant and will continue to assess any threats and develop plans accordingly'.[32]

Just over a year later in October 2019, and within the context of a visit by the Home Secretary, Priti Patel, it was announced that the NPoCC alongside the International Crime and Coordination Centre (ICCC) are 'at the heart of law enforcement’s preparation for the UK’s exit from the European Union on 31 October (2019).[34] In a statement regarding their preparations for a potential no deal Brexit, The National Police Coordination Centre said: 'Officers have been taking part in exercises with colleagues from other emergency services and local resilience forums (LRFs) to ensure a joined-up response' and 'tested their established plans to move officers around if necessary, through mutual aid. This process is routinely used multiple times a year'.[35]

Extinction Rebellion Protests - October 2019

One of the most heavily publicised uses of the NPoCC mutual aid function took place during the Climate Change protests organised by Extinction Rebellion (XR) in October 2019. All 44 British forces (including Police Scotland) gave 'mutual aid'.[36] The National Police Chiefs' Council said '500 officers [were] drafted in from across England and Wales, with police being sent from all the 10 regional organised crime units that cover the two countries'.[37][38][37] This also included 100 officers from Scotland[39]

According to Met Commissioner Cressida Dick the policing had cost £37m.[40] In November 2019, the High Court found that the use of Section 14 of the 1986 Public Order Act by the Metropolitan Police to ban all XR protests was unlawful.[41]

Senior Officers

Owen Wetherill

The most Senior post in the NPoCC is that of 'Strategic Lead',[42] this is the officer reporting to the Chair of the NPCC.[2]

From July 2019, this post was held by Assistant Chief Constable Owen Weatherill.[42]

- Owen has spent 26 year with Hertfordshire Constabulary, gaining a wide range of operational and command experience. He spent the majority of the first 16 years as a Detective in a range of roles up to DCI and as an SIO. This also included informant handling, undercover management, managing intelligence functions [...] He is an experienced Gold Commander for Firearms, Public Order & CBRN. Within the Public Order and Public Safety environment, he has wide experience at Bronze, Silver and Gold command levels, across a broad range of events. These include 2012 Olympics venue command, 2012 Olympic Torch relay, political/international conferences, a variety of protests and demonstrations, as well as sporting events and music festivals.[42]

Nigel Goddard

In 2020, Wetherill was succeeded as 'Head of the NPoCC' by Chief Superintendent Nigel Goddard. Before that he held the post of Deputy Head between June 2018 and Febuary 2020.[43] Goddard was in the RUC/Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) for 25 years, with most of his time spent in uniform operational policing.[42] Goddard was the Head of the PSNI’s Operations Branch with responsibility for Public Order Units, Armed Response Units and Roads Policing.[42] 'He is a qualified Bronze, Silver and Gold Public Order Commander [...] with significant experience in managing large scale public order and public safety events'.[42] As part of the PSNI, he was involved in the policing of the G8 in Northern Ireland. The announcement also states: 'his current area of academic interest relates to understanding perceptions of Police Legitimacy in a public order context'.[42]

Howard Hodges

Superintendent Howard Hodges became the Deputy Head of Unit in February 2020.[42] Before this, he was employed by Sussex Police for 25 years. Prior to his secondment to NPOCC, he worked as a Superintendent within the Surrey and Sussex collaborated Operations Command, where Hodges had responsibility for a range of teams including operational dogs, public order and CBRN.[42]

It is stated that Howard had experience in the protracted oil and gas protests (the anti-fracking protests at Balcolmbe) and the Labour Party conference in Brighton' as well as public order operation during Brighton and Albion Football matches.

Previous Senior Staff

Chris Greany

Commander Chris Greany was appointed the head of the NPoCC in September 2014, replacing Stuart Williams.[44][45] Greany started his career 27 years ago in the Metropolitan Police in 1987 and also worked in the City of London Police. He has spent much of that time in counter terrorism, intelligence, investigations and security. He previous role before working for the NPoCC, was head of the NPCC's 'domestic extremism unit - the NDEDIU - which he created from the scrapped National Domestic Extremism Unit (NDEU).[46] He retired from the police in 2017 during an investigation for who is being investigated for his alleged involvement in destroying files held on a Green party peer, Baroness Jenny Jones meaning that he avoided any possible disciplinary action.[47] On retirement, he went to the private sector, first working for Barclays Bank as a Chief Security Officer, dealing with 'insider threats'.[48] Greany now works as a cyber security consultant for Templar Executives.[49]

Stuart Williams

Assistant Chief Constable Stuart Williams was the 'strategic lead' for the NPoCC from at least September 2014 and was suceeded as senior officer by Chris Greany.[21]

Chris Shead

Chris Shead is described in a report written on behalf of the NPoCC in 2016 as a 'Assistant Chief Constable form Thames Valley Police, currently seconded to the NPoCC. It is stated that he is a qualified public order 'Gold Commander, CBRN Gold Commander, Strategic Firearms Commander and Counter-Terror Commander'.[50] It states that Shead has experience of being overall command of a number of public order incidents and other events including English Defence League marches, Animal Rights protests, industrial disputes and football matches.[50]

After his stint with the NPoCC, in 2017, Chris Shead returned to Thames Valley Assistant Chief Constable and was 'the new National Lead for Public Order and Public Safety'.[51] He since retired from the police and is a 'Business Change Consultant - Emergency Services (contract) at Floch Ltd'.[52]

NPoCC Strategic Intelligence & Briefing Team

In a job description for a Deputy Head of the NPoCC (placed in November 2019) it was said that the role would include: '[...] developing and delivering a new national Public Order and Protest intelligence capability'.[53] Following this, a new sub-unit within the NPoCC called the Strategic Intelligence and Briefing Team (SIB) was formed - with a number of posts being advertised in Summer 2020.[54] The brief for the jobs ranging in rank from Detective Inspectors to PC's included:[54]

- [...] the development and flow of intelligence relating to aggravated activism, strategic protest and significant public order events across the United Kingdom (UK) to identify and mitigate risk, harm and threat. Day-to-day responsibilities include supporting SIB intelligence analysts and police officers by interrogating police indices to develop and maintain intelligence profiles, populate databases, conduct open source research and contribute to the production of threat assessments and briefing documents.

It is notable the brief appears to contain a new (and undefined) term: 'aggravated activism'. A previous term, 'domestic extremism' had stopped being used by the Home Office in 2019 to describe political activists after a lengthy campaign by Netpol.[55][56] The term 'aggravated activism' is thought to replace this.

One of the posts also stated:[54]

- The SIB provides intelligence and assessment for both police and law enforcement stakeholders (including HMG) and forms part of the National Police Coordination Centre’s folio.[54]

One of the posts also mention that the holder would be responsible for the 'Thematic Desk'.[54] This is suggestive that as with previous units investigating and monitoring activists and the social movements they belong to and other subsequent units SBIS will be divided by type of 'aggravated activism' and 'strategic protest'.[54] For instance, the NPIOU had a 'environmental desk'[57] and Special Branch before that had a 'Black Power' desk.[58] In its original brief, the NPoCC was to work closely with the NDEU.[1] It is unclear whether this new unit replaces or complements work done by the latter's successor unit, the National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit (NDEDIU).

Reviews

The NPoCC works with NPCC Committee Leads and the College of Policing 'to develop an on-going exercising regime to test police mobilisation in response to a variety of scenarios including natural disasters and wide scale disorder':[14]

- We link in with regional and national police exercises to identify relevant learning regarding mobilisation from effective debriefing and build them in to future working practice. We develop working relationships with a wide range of stakeholders to ensure effective processes are in place to support partners during times of crisis and the impact events can have on police mobilisation. These include; the Ambulance Service, Fire & Rescue Service, National Crime Agency (NCA), Military, Government Departments and other service providers.

Bermuda Protests

Chris Shead, conducted a review if policing on behalf of the NPoCC of a protest regarding the controversial development of the local airport at the House of Representatives in Bermuda (a British overseas territory).[50] Disruption to the parliament and scuffles between police and protesters escalated, until the officers withdrew and parliament was suspended for the day.[50]

The report examined planning, command and tactical issues of the policing of the protest.[50]

The report contains qualified criticisms of the Bermudian police operation. Its main interest lies in the interpretation of how policing such can provoke the crowd. For instance, Shead writes: 'When informed that they [the protesters] would be liable to arrest unless they allowed [delegates] access to the gates [of the parliament] the crowd surged and some of the officers were assaulted.'[50]

More generally, Shead characterises public order policing thus:

- It is seldom aesthetically pleasing and will quite often appear chaotic. This is simply because no matter how good the planning has been, when faced with a committed group of protestors, the plan will need to be adapted to reflect the dynamics of the crowd and react to their activities.[50]

Operation Skep

'Operation Skep' was a Kent Police operation to control pro-refugee/anti-fascist and right-wing protests in Dover, Kent in February 2016. There was physical conflict between the two groups of protesters, and disruption to the town became a cause for complaint from businesses and others from the locality. A review of policing undertaken by the NPoCC and was also authored by Chris Shead which 'vindicated' the police tactics.[59]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Police launch national coordination centre to mobilise officers in times of need NPCC, 23 April 2013 (accessed 14 June 2020).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Section 22 Agreement Eversheds, 2015 (accessed 29 June 2020).

- ↑ England riots: Maps and timeline BBC News (website) 15 August 2011 (accessed 20 June 2020).

- ↑ Chris Gilson, The initial Metropolitan Police handling of the Tottenham riots shows a depressing failure to learn lessons from recent history LSE Blog, 8 September 2011 (accessed 20 June 2020).

- ↑ Mark Townsend, Revealed: how police lost control of summer riots in first crucial 48 hours The Guardian, 3 December 2011 (accessed 20 June 2020).

- ↑ David Green, London riots: why did the police lose control? Daily Telegraph, 8 August 2011 (accessed 20 June 2020).

- ↑ See Paras: 4.37 - 4.49 in HMIC, The rules of engagement: A review of the August 2011 disorders, 2011 (accessed 20 June 2020).

- ↑ National Police Coordination Centre (NPoCC) a year on 23 April 2014 (accessed 20 June 2016).

- ↑ Note: It might be said that the NPoCC's public order function has its antecedents in the National Reporting Centre in the early 1970's. See: Connor Woodman, ACPO and the emergence of national political intelligence – Part 1: 1968-75, From Grosvenor Square to Flying Pickets Special Branch Files Project (website), 2 April 2019 (accessed 24 June 2020).

- ↑ Note: It is unclear where exactly the responsibilities between the CTPOC and NCTP HQ falls. However, while CTPOC is part of the Metropolitan Police and NCTPHQ part of the NPCC, it is traditionally the same officer of Assistant Commissioner rank with the Metropolitan Police has overall responsibility for both units. See:Terrorism and Allied Matters, NPCC, undated (accessed 23 June 2020).

- ↑ Note: On the Counter Terrorism Police website it is explained: 'At the centre of the network sits the Counter Terrorism Policing Headquarters (CTPHQ), which devises policy and strategy, coordinates national projects and programmes, and provides a single national Counter Terrorism Policing voice for key stakeholders including government, intelligence agencies and other partners.Alongside the headquarters is the National Operations Centre, a central command made up of units that provide operational support to the national network.The National CBRN Centre brings together the emergency services to protect and prepare the UK against the chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) threat. Other parts of the network include regional Special Branches and other special units'. See:Our Network, Counter-Terror police, undated (accessed 4 July 2020).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 NPCC minutes 22 April 2015 NPCC, 22 April 2015 (accessed 1 July 2020).

- ↑ NPCC Minutes 20 April 2017 NPCC, 20 April 2017 (accessed 1 July 2020).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Areas of Work NPCC, undated (accessed 16 June 2020).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Civil emergencies Mobilisation College of Policing, 27 January 2016 (accessed 17 June 2020).

- ↑ The Strategic Policing Requirement HMIC, April 2014 (accessed 1 July 2020).

- ↑ Susan Patterson, 5-6 April Minutes 2017 NPCC, (accessed 1 July 2020).

- ↑ Haroon Sidique, G8 summit sparks biggest police operation in Northern Ireland's history The Guardian, 20 June 2013 (accessed 22 June 2020).

- ↑ Note: see profile of Jason Bishop for an account of the public order and undercover operations.

- ↑ Call Out G8 Rhythms of Resistance, 20 February 2013 (accessed 22 June 2020).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 NPoCC A Year on NPCC, 23 April 2014 (accessed 22 June 2020).

- ↑ Luke Starr, Controversial gas 'fracking' extraction headed to Europe The Guardian, 1 December 2010 (accessed 8 July 2020).

- ↑ Martin Lukacs, New Brunswick fracking protests are the frontline of a democratic fight The Guardian, 21 October 2013 (accessed 22 June 2020).

- ↑ Along with the anti-austerity campaign 'UK Uncut'.

- ↑ Protecting the Protectors Network for Police Monitoring, November 2016 (accessed 24 June 2016).

- ↑ W. H. Jackson, J. Gilmore and H. Monk, Policing unacceptable protest in England and Wales: A case study of the policing of anti-fracking protests 2018 (accessed 23 June 2020).

- ↑ Public Order Gold Command 2’ Hydra Exercise 9 October 2014 (accessed 23 June 2020).

- ↑ Policing of anti-fracking protest in Lancashire Northumbria PCC, 1 August 2017 (accessed 22 June 2020).

- ↑ Policing linked to policing Onshore Oil and Gas Operations: Briefing on the National Police Chief's Council's Guidance Netpol, September 2015 (accessed 22 June 2020).

- ↑ Overnight Allowance NPCC, 3 July 2018 (accessed 1 July 2020).

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Vikram Dodd, Trump UK visit: police to mobilise in numbers not seen since 2011 riots The Guardian, 9 July 2018 (accessed 1 July 2020).

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 Caroline Wheeler, Police plan for riots and crimewave if there is no-deal Brexit The Sunday Times (paywall), 9 September 2018 (accessed 24 June 2020).

- ↑ Charlie Hall Hertfordshire Police, undated (accessed 4 July 2020).

- ↑ Home Secretary visits the police hubs leading Brexit preparations Home Office, 8 August 2019 (accessed 23 June 2020).

- ↑ UK policing as prepared as possible for a potential no-deal EU exit NPCC, 11 Oct 2019 (accessed 23 June 2020).

- ↑ Met calls in police reinforcements to handle Extinction Rebellion London protests City AM, 9 October 2019 (accessed 15 June 2020).

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Lucy Leeson, Yorkshire officers sent to London to police Extinction Rebellion protests The Yorkshire Post, 9 October 2019 (accessed 15 June 2020).

- ↑ Tom Seward, Police officers sent to London to deal with Extinction Rebellion protests Swindon Advertiser, 10 October 2019 (accessed 15 June 2020).

- ↑ Extinction Rebellion protests: Scots officers to assist in London BBC News (website), 12 October 2019 (accessed 15 June 2020).

- ↑ Vikram Dodd, Extinction Rebellion protests cost Met police £37m so far The Guardian, 22 October 2019 (accessed 15 June 2020).

- ↑ Extinction Rebellion: High Court rules London protest ban unlawful BBC News (website), 6 November 2019 (accessed 29 June 2020).

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 42.5 42.6 42.7 42.8 Team NPCC, undated (accessed 29 June 2020).

- ↑ Note: On Goddard's linkedin profile is states that he still is 'Deputy Head' of the NPoCC. See:Nigel Goddard LinkedIn (website), undated (accessed 29 June 2020).

- ↑ Christopher Greany appointed to lead National Police Co-ordination Centre, The Security Lion (blog), 24 September 2014 (accessed 1 July 2020).

- ↑ Commander Chris Greany, NPoCC Blog NPCC, 8 July 2015 (accessed 1 July 2020).

- ↑ National Police Coordination Centre (NPoCC) appoints new head NPCC, 24 September 2014 (accessed 1 July 2020).

- ↑ Rob Evans,Retiring police chief will avoid any discipline over alleged coverup The Guardian, 28 March 2017 (accessed 1 July 2020).

- ↑ Leading Questions Chris Greany Barclays Bank, 9 April 2018 (accessed 1 July 2020).

- ↑ Chris Greany Linkedin (website), no date (accessed 1 July 2020).

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 50.5 50.6 Chris Shead, Assistant Chief Constable, Peer Review on House of Assembly Protests, NPoCC, undated (accessed 17 June 2020).

- ↑ Protecting the Protectors Network for Police Monitoring, undated (accessed 20 June 2020).

- ↑ Chris Shead (profile) Linkedin (website), undated (accessed 29 June 2020).

- ↑ Deputy Head of Unit - National Police Coordination Centre NPCC, November 2019 (accessed 30 June 2020).

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 54.4 54.5 Career Opportunities undated (accessed 29 June 2020).

- ↑ Domestic Extremism Netpol, undated (accessed 29 June 2020).

- ↑ Victory, Netpol, 9 August 2019 (accessed 29 June 2020).

- ↑ Eveline Lubbers,Officer anonymity threatens the integrity of the Pitchford Inquiry Open Democracy, 31 October 2016 (accessed 29 June 2020).

- ↑ Eveline Lubbers, Black Power Desk Special Branch Files Project, 17 September 2017 (accessed 29 June 2020).

- ↑ Protest Policing Vindicated Police Review, 1 April 2016 (accessed 29 June 2020).