Domestic Extremism

This article is part of the Undercover Research Portal - a project of the Undercover Research Group in conjunction with SpinWatch. |

Domestic Extremism is a police term which seeks to categorise a particular kind of political activity. The term is often used to distinguish so-called single issue campaigns or political groups with a militant edge from terrorist groups. Animal rights, ecological defence, anti-arms trade, the radical left and the far right have been labelled domestic extremists, as have individual actors such as the letter-bomber Miles Cooper.

The Government has no formal legal definition for Domestic Extremism (while it has one for terrorism for instance). The use of the label has come under criticism for mission creep, for political policing and for using it as a way to treat protest as a form of crime: a number of people who had no criminal record were nevertheless added to the National Domestic Extremism Database. However, in 2014 a revised working definition was provided by the Metropolitan Police as:[1]

- Domestic Extremism relates to the activity of groups or individuals who commit or plan serious criminal activity motivated by a political or ideological viewpoint.

It is a term mostly used by British police, in particular by the secret units that were running undercover officers like Mark Kennedy, following up Special Branch's Special Demonstration Squad. The history of relevant police units with ever-changing acronyms residing under the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) can be found at the page of the National Domestic Extremism Unit.[2]

Contents

Origins of the term

- See also National Domestic Extremism Unit.

The use of the full term 'Domestic Extermism' seems to have emerged between the second half of 2004 and the start of 2005. Prior to this, militant animal right activism had been referred to as 'Animal Rights Extremism' (ARE), while ecological direct action was commonly called eco-terrorism.[3] In 2004, after a number of successful animal rights campaigns against vivisection, the New Labour government was under pressure from the pharmaceutical industry to take action. In a July 2004 paper called 'Animal Welfare - Human Rights: protecting people from animal rights extremists' the Home Office announced the creation of the National Extremism Tactical Coordination Unit (NETCU) and the appointment of a national co-ordinator Anton Setchell to oversee efforts to counter the threat from AREs.[4]

Examination of known police documents, parliamentary papers and media coverge from the time show no mention of 'domestic extremism' in July 2004 in the UK. There is however mention of 'domestic terrorism' in FBI documents, defined as:[5]

- Domestic terrorism involves acts of violence that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or any state, committed by individuals or groups without any foreign direction, and appear to be intended to intimidate or coerce a civilian population, or influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion, and occur primarily within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States.

In this, the label is being used to cover to both 'animal rights extremism' and 'eco-terrorism'.

With the experience of armed struggle in the shape of Irish republicanism, 'domestic terrorism' has a different resonance in Britain, which may have been the reason to consider it inappropriate to use. A solution was found in the term ‘Domestic Extremism'. The first identified use of the term occurs in January 2005, within the full title of Assistant Chief Constable Anton Setchell as 'National Co-ordinator (for) Domestic Extremism',[6], while the primary focus of his unit's work at the time was animal rights campaigns such as Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty.[7] Though the domestic extremism units maintained focus on animal rights, they had by 2009 extended their remit to crimes 'linked to single issue-type causes and campaigns', according to Anton Setchell.[8] There are a number of reasons as to why the broadening may have happened:

- One of the units brought under Setchell's control in 2006 was the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU founded in 1999) that already had a public order remit, allowing it to extend its work beyond animal rights to other left wing protest. One of its functions was bringing together the Animal Rights National Index and the Southern and Northern Intelligence Units which had a focus on hunt saboteurs, free parties and travellers among others.[9]

- It was the NPOIU which developed Special Branch's Animal Rights National Index into the National Domestic Extremism Database.[10]

- Many of the various groups on the left and in the environmental movement had an overlap in individuals; the same people may have been involved in activism carried out in the name of the Animal Liberation Front and Earth Liberation Front, hunt sabs and anti-fascist activity, tree-protest and street party / anarchist groups such as Reclaim the Streets.[11]

- The targeted industries did not distinguish between the different types of protest, and considered all protest as criminal behaviour. The mounting political pressure mentioned above resulted in an increasing willingness within the domestic extremism units, particularly NETCU, to collaborate with industry.[12] This has been recognised within activist circles as part of a wider policing agenda to crack down on protest, in particular the politicisation of the policing of public dissent dating back to the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.[13][14]

Undercovers at work

The broader remit also shows in the work of the exposed undercover agent. They all focused on environmental, anarchist and summit protests groups. The G8 protest at Gleneagles in 2008 (and in particular the Eco-Village ('Hori-zone') at Stirling) saw many thousands of protestors from across the left converge together, from environmentalists to anarchists. Spying on it was NPOIU agent Mark Kennedy, whose material was apparently making its way to the desk of Prime Minister Tony Blair.[15] The Eco-village was the model for the 2006 Camp for Climate Action at Drax in East Yorkshire, which had also been infiltrated by Kennedy and another spy Lynn Watson. Internal police documents seen by Guardian journalists, show that the Camp, from the policing perspective, was pivotal as it was 'the first time domestic extremism took place against national infrastructure in the county'.[8] It would be followed in 2007 by the even higher profile Camp at Heathrow airport.

In October 2009, in an article entitled "How police rebranded lawful protest as 'domestic extremism'", the Guardian wrote that the term domestic extremism was now common currency within the police.[8] It has remained in use since, particularly in the latest re-incarnation of the spying unit as the National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit.

'Domestic extremism' appears to be a purely British term, and it does not appear in the annual EU Terrorism Situation and Trend Reports (TE-SATs) from Europol, which tends to use the phrase 'single issue terrorism' or 'single issue extremism'.[16]

It is worth noting that many of the groups now being monitored by the Domestic Extremism units, such as the radical socialist left (Communist, Maoist & Trotskyist organisations) and peace / nuclear disarmament groups would traditionally have been also the province of MI5 in its counter-subversion role in conjunction with Special Branch.[17]

Earlier uses: Extremism v. Counter-Subversion

Counter-subversion, the countering of elements seen in society as subversive, was since 19391 domain of MI5. For much of the 20th Century they treated it as equivalent to the activities of the Communist Party, and to a lesser degree the activities of groups such as Mosley's British Union of Fascists. MI5 had its own counter-subversion desk, usually denoted F4.[18]

The disinction between the use of the term extremism and subversion was seemingly carefully drawn as the following exchange from a 1969 trial of an anti-Apartheid protester.[19] Detective Chief Inspector Elwyn Jones, a Metropolitan Police Special Branch officer most likey with 'C Desk' is answering questions put by a Mr. Capstick:[20]

- Q Mr. Jones, you are of the Special Branch, are you?

- A Yes, sir.

- Q What is the Special Branch?

- A It is part of the Metropolitan Police, sir, which specializes in subversive political organisations.

- Q Subversive?

- A Can I withdraw that and say extremist, sir?

- Q Not subversive?

- A No. I made a mistake there, sir. I apologise. I should not have said that, sir.

Evolving definition

2009: '...taking a vague stab'

The meaning of the term 'domestic extremism', appears to have been ill-defined - at least initially (and possibly deliberately so). In 2009 the Guardian reported senior police as taking 'a vague stab' at interpreting it to describe individuals or groups "that carry out criminal acts of direct action in furtherance of a campaign. These people and activities usually seek to prevent something from happening or to change legislation or domestic policy, but attempt to do so outside of the normal democratic process. "[8]

By then, four categories of domestic extremism had been developed for the ACPO units:[21]

- animal rights

- far right groups - e.g. EDL

- extreme left-wing - e.g anti-war

- environmental extremism: Camp for Climate Action, Plane Stupid

When challenged in Parliament on the police use of the term for labelling protestors, then Home Secretary Alan Johnson said: "I haven't issued any guidance on the definition of that phrase. The police know what they are doing, they know how to tackle these demonstrations, they do it very effectively."[22]

The NETCU created handbook Beyond Lawful Protest: Protecting Against Domestic Extremism, in its 2009 re-issue states:[23]

- "The majority of protest activity in the UK is both lawful and peaceful and is carried out by law abiding citizens who wish to exercise their freedom to assemble and protect themselves; these freedoms are an important part of our democracy and are protected within the Human Rights Act 1998. Unfortunately there are a small number of people who are prepared to break the law in the belief that it will further their 'cause'. It is this unlawful activity which is beyond lawful protest that we refer to as domestic extremism. "

In contrast to this, NETCU at the time was supporting civil injunctions against various campaign groups which had the potential to effectively outlaw protest altogether.[24][25] This included an injunction taken out by Heathrow Airport against climate change protestors which was so wide as to take in approximately 4 million people.[26][27]

The most telling view of domestic extremism and how it has been handled within the wider Government is offered by the Ministry of Justice in the National Offender Management Service (NOMS) guidance 2009.[28] The guide emphasises that "Domestic Extremism does not include offenders who are viewed as terrorists" and shows that an extra, rather vague category has been added to the four quoted above:

- 5. "Emerging Trends – or any activities that unduly and illegally influence or threaten the economic and community cohesion of the country."[29]

The NOMS Extremism Unit also produced a number of definitions as an ‘aide memoir’ for their staff. Supposedly useful in the identification of a Domestic Extremist, it can be found at the dedicated NOMS Guidance 2009 page.

2010 - 2011: '...activities outside the normal democratic process'

Guidelines from the NETCU website, cited in 2010 (website has since been taken down) gave the following:[30]

- There are a small number of single-issue groups and individuals who have pursued a determined course of criminal activity in recent years in the name of issues ranging from animal rights to GM crop studies.

And defines extremists as those:

- whose activities go outside the normal democratic process and engage in crime and disorder.

This was echoed on the National Coordinator Domestic Extremism Frequently Asked Questions webpage (2010-2011):[31]

- Who is considered a domestic extremist?

Single issue protest campaigns are regularly facilitated by police and local authorities who each have a duty to uphold the rights of individuals and groups to protest in public.

However, in recent years, a small number of groups and individuals have pursued a determined course of criminal activity designed to disrupt the public peace and lawful business, and at worst, repeatedly victimise selected individuals.

This activity has ranged from blackmail and serious intimidation in the name of animal rights; bombing campaigns by violent and racist individuals associated with far right wing groups; violent disorder from left wing or anarchist individuals, to large scale criminal damage against scientific GM crops studies and mass aggravated trespass or unlawful obstruction of lawful businesses associated with the national infrastructure of our country, such as power stations and airports by those whose stated aim is to stop any business perceived to harm the environment.

- Who is considered a domestic extremist?

In contrast, at this time the Government defined extremism as:[32]

- vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs. We also include in our definition of extremism calls for the death of members of our armed forces, whether in this country or overseas.

2012 - 2013: '...includes all forms of criminality, no matter how serious'

HM Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) released a report in June 2012 entitled 'A Review of National Police Units which Provide Intelligence on Criminality Associated with Protest'[33] which made a number of points on how the police were using the term domestic extremism at the time:

- The term was coined some point shortly after 2001 (though no evidence is cited in support of this. It may refer to the 2001 Home Office document "Extremism - Protecting People And Property" a precursor to the later NETCU publication "Beyond Lawful Protest: Protecting Against Domestic Extremism).

- The Association of Chief Police Officers, which oversaw the domestic extremism units, stated: 'Domestic extremism and extremists are the terms used for activity, individuals or campaign groups that carry out criminal acts of direct action in furtherance of what is typically a single issue campaign. They usually seek to prevent something from happening or to change legislation or domestic policy, but attempt to do so outside of the normal democratic process. Their activity is more criminal in its nature than that of activists but falls short of terrorism'.[34]

- The term ‘extremism’ is used within the PREVENT strategy, part of the Government's counter-terrorism programme and implemented in conjunction with the police: "Extremism is defined as the vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs. We also include in our definition of extremism calls for the death of members of our armed forces, whether in this country or overseas." [35]

- HMIC expressed the view that the term "domestic extremism" should be 'limited to threats of harm from serious crime and serious disruption to the life of the community arising from criminal activity. The deployment of undercover officers in response to a threat of serious disruption from criminal activity will always require both a very careful assessment of the proportionality of the proposed deployment and close control of the undercover officer when it is under way. Deployments in this category should occur only in exceptional circumstances in which the level of disruption anticipated is very high, and the level of intrusion carefully calibrated to the threat.'

- It noted of the ACPO definition that it:

- 'includes all forms of criminality, no matter how serious. It could lead to a wide range of protestors and protest groups being considered domestic extremists by the police. HMIC questions whether this is appropriate, and if the police should instead reserve this potentially emotive term for serious criminality.'

- and that there should be a distinction drawn between domestic extremism and public order issues:

- 'However, the deployment of undercover officers to tackle serious criminality associated with domestic extremism should not be conflated with policing protests generally, as it is unlikely that the tests of proportionality and necessity would be readily satisfied in the latter case.'

In light of this, HMIC made the following recommendation to ACPO and the Home Office:

- In the absence of a tighter definition, ACPO and the Home Office should agree a definition of domestic extremism that reflects the severity of crimes that might warrant this title, and that includes serious disruption to the life of the community arising from criminal activity. This definition should give sufficient clarity to inform judgements relating to the appropriate use of covert techniques, while continuing to enable intelligence development work by police even where there is no imminent prospect of a prosecution. This should be included in the updated ACPO 2003 guidance.

The definition as used by the police as given in the 2012 HMIC report was in still in place at the time of a June 2013 review of progress made from that report.[36]

2014: '...serious criminal activity motivated by a political or ideological viewpoint'

In response to a Freedom of Information Request, a 2014 communication from the Metropolitan Police Service stated:[1]

- I would like to explain that there is no legal definition of Domestic Extremists and so these individuals may not be classified as potential domestic extremists.

- However a new definition was recently agreed and publicised by the Commissioner at a MOPAC [The Mayor's Office for Policing And Crime] challenge panel.The new working definition of Domestic Extremism is therefore:

- "Domestic Extremism relates to the activity of groups or individuals who commit or plan serious criminal activity motivated by a political or ideological viewpoint."

Referring to this new definition, the National Coordinator - Domestic Extremism, DCS Chris Greany in an answer to Jenny Jones, member of the London Assembly, explained that:[37]

- ...the agreement to change the definition of Domestic Extremism was made at the end of October 2013, by the then Head of National Counter Terrorism Functions. During November 2013 the NDEDIU (National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit) began to introduce this as a working definition whilst it went through the process of amending internal processes, updating the national police network and working with ACPO particularly around updating the definition on the ACPO website... The process was not completed until January 2014...

...(T)he new definition applies to those who plan or commit acts of serious criminality, and low levels of civil disobedience would not usually apply, it could apply like any other form of action if it caused serious criminality.

- ...the agreement to change the definition of Domestic Extremism was made at the end of October 2013, by the then Head of National Counter Terrorism Functions. During November 2013 the NDEDIU (National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit) began to introduce this as a working definition whilst it went through the process of amending internal processes, updating the national police network and working with ACPO particularly around updating the definition on the ACPO website... The process was not completed until January 2014...

The MI5 website in 2014 makes an effort to distinguish between 'public order' issues (handled by the police) and threats to 'national security' (the remit of MI5). The mention of Northern Ireland shows the fine line between what is considered 'domestic extremism' and what as 'terrorism':[38]

- Domestic extremism mainly refers to individuals or groups that carry out criminal acts of direct action in pursuit of a campaign. They usually aim to prevent something from happening or to change legislation or domestic policy, but try to do so outside of the normal democratic process. They are motivated by domestic causes other than the dispute over Northern Ireland’s status.

At various times in the recent past, a range of groups have fallen into this category. They have included violent Scottish and Welsh nationalists, right- and left-wing extremists, animal rights extremists and other militant single-issue protesters....

For the most part the actions of domestic extremists pose a threat to public order, but not to national security. They are normally investigated by the police, not the Security Service.

- Domestic extremism mainly refers to individuals or groups that carry out criminal acts of direct action in pursuit of a campaign. They usually aim to prevent something from happening or to change legislation or domestic policy, but try to do so outside of the normal democratic process. They are motivated by domestic causes other than the dispute over Northern Ireland’s status.

In September 2015, it emerged that the Prevent programme was still pushing a broad definition of extremism: at a Prevent training session organised by West Yorkshire Police for teachers, an example of extremism given was the arrest of Green MP Caroline Lucas at an anti-fracking protest.[39]

Criticism

A number of criticisms have been levelled against the use of the term 'domestic extremism'.

Criminalisation of Protest

A frequent criticism is that it has led to the criminalisation of protest and the intimidation of otherwise lawful protest,[22][24] amounting to political policing.[40] This is partly due to activities of National Public Order Intelligence Unit officers and Forward Intelligence Teams actively monitoring and recording details at open meetings, lawful assemblies and marches and other gatherings not directly involved in protest.[41] A number of campaigners have sought to have their details removed from the National Domestic Extremism Database (see that page) on the grounds that the activities they had been engaged in were lawful. In particular, campaigner John Catt has engaged in a long civil case to have his details removed from the National Domestic Extremism Database, arguing that as a peaceful and lawful protestor, he should not have had his details included on the system. To be classified as a domestic extremist amounted to victimisation for taking part in political protest and is incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights.[42]

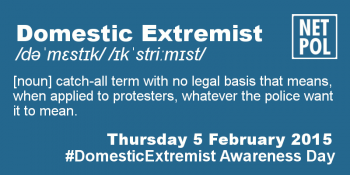

The Network for Policing Monitoring took lead on campaigning against the use of the term and the criminalising of protest. This included inaugurating the annual Domestic Extremism Awareness Day which took place on 5 or 6 February from 2013 to 2019.[43] In February 2019, John Catt won his case in the European Court of Human Rights, leading to increased pressure on the police and governments use of the term.[44][45] However, a report published in July 2019, showed that in 2018 the government had been discussing ending use of the term (see below).

Broad Definition

Due to criticism in the above mentioned 2012 HMIC report of how the database was being maintained and the quality of the material in it, changes were carried out and reviewed in 2013.[36] The definition now contained the term 'serious criminality', which the Network for Police Monitoring (NetPol) notes is a problematic term, because the criteria for what amounts to a 'serious crime' were rather broad:[46]

- Where a person with no previous convictions 'could reasonably be expected to be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of three years or more' (Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 - RIPA); or

- That the conduct involves the use of violence, results in substantial financial gain or is conduct by a large number of persons in pursuit of a common purpose.

NetPol pointed out that the broadness of this belies what might commonly be thought of as a serious crime and undermines the impression being given that the definition has been narrowed. In 2014, NetPol started a campaign to encourage people to make a request under the Data Protection Act to find out whether files were held on them. Campaigner Kevin Blowe[47] and former member of the Police Metropolitan Authority and Green Party member of the London Assembly Baroness Jenny Jones[48] both found their details were recorded on it despite neither being associated with criminality.

Confusing Remit

The 2012 HMIC report also noted that the remit of the domestic extremism units was confusing in itself: they had responsibility for monitoring both public order and domestic extremist groups. This criticism was also highlighted in the HMIC report on public order policing following the London riots two years earlier.[49]

Referring to this report, the Guardian wrote:[50]

- The Home Office has poured millions of pounds into a drive to tackle so-called domestic extremism, a term (HMIC Chief Inspector of Constabulary, Denis) O'Connor said was "pretty wide-ranging" and failed to distinguish between people with genuinely violent intent and others involved in peaceful demonstration. He called for a new definition of domestic extremism, which he said had been conflated with policing big demonstrations. His inspectors concluded that a national database of domestic extremists contained details about protesters that should not be held.

David Howarth, a law professor and former LibDem MP, has said of domestic extremism that it was 'an astonishing conflation of legitimate protest with terrorism'.[30] and also that:[22] 'an alphabet soup of agencies appears to have decided to put everyone in this country who protests about anything on a list of suspects... This is an example of mission creep, they have gone beyond their original intention of dealing with violent animal extremists'.

David Mead, the author of The Law of Peaceful Protest, stated that, in particular, any protest that is obstructive or disruptive is seen as criminal, whether or not it amounts to a 'serious crime'.[51] Guardian editor Seamus Milne pointed out that the number willing to use 'extremist actions' are few in number and that the government is reacting disproportionately and at the cost of human rights. [34][52] He also warned that the domestic extremism units were going beyond monitoring activists, to working with private industry to prevent activists from continuing to demonstrate and protest.[53][54]

Pennie Quinton makes a related point, noting that the vagueness of the label 'domestic extremism' helps the police justify abusing anti-terror laws to target legitimate protest.[55]

Mission Creep: Domestic Extremism in the Counter-Terrorism context

A little examined question is the issue of housing many of the domestic extremism units within or along side counter-terrorism units. For instance, a number of police forces now have "counter-terrorism and domestic extremism units". The National Coordinator for Domestic Extremism / National Domestic Extremism Unit was established under the Terrorism and Allied Matters committee of the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO TAM), and subsequently passed to the control of Counter Terrorism Command within the Metropolitan Police. A clear example of this in action is The City of London Police's 'Project Servator', supposedly monitoring 'hostile reconnaissance' makes no distinction between 'extreme protest groups, organised crime groups or terrorists'.[56] Elsewhere it can be noted, that former NETCU publications such as "Beyond Lawful Protest: Protecting Against Domestic Extremism" were subsequently published by the National Counter Terrorism Security Office (NATSCO).[23]

In a 2013 speech, James Brokenshire, the Home Office Minister for Crime and Security made much of how counter-terrorism initiatives such as PREVENT were being used to tackle home-grown far-right extremism:[57] This indicates that those in charge of 'domestic extremism policing' are part of the wider process where social matters are being treated as a security issue (called 'securitising social policy' in the jargon) and thus much of the criticism levelled in 2009 has remained valid subsequently. One of the few criticisms of the increasing role of 'securocrats' in deciding policy has come from the Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police, Sir Peter Fahy, who is also a vice chair of ACPO TAM.[58]

It is to be noted that unlike domestic extremism, there is a formal definition of 'terrorism' in UK law, as set out in Section 1 of the Terrorism Act 2001, where it is defined as:[59]

- The use or threat of action designed to influence

- the government or an international governmental organisation, or

- to intimidate the public, or a section of the public

- made for the purposes of advancing a political, religious, racial or ideological cause; and it involves or causes:

- (a) serious violence against a person;

- (b) serious damage to a property;

- (c) a threat to a person's life;

- (d) a serious risk to the health and safety of the public; or

- (e) serious interference with or disruption to an electronic system.

Clearly, though this includes groups and individuals covered by the definitions of domestic extremism and has also been criticised as being too broadly worded[60] and as criminalising dissent and extra-parliamentary action.[61]

Justification

In response to people objecting to being monitored in this way, Anton Setchell responded in 2009:[21]

- What I would say where the police are doing that there would need to be the proper justifications.

An ACPO spokesperson in the same year also said:[22]

- There are lots of reasons why people might be on the database. Not everyone on there is a criminal and not everyone on there is a domestic extremist but we have got to build up a picture of what is happening. Those people may be able to help us in the future. It's an intelligence database, not an evidence database. Protesting is not a criminal offence but there is occasionally a line that is crossed when people commit offences.

Jon Murphy, a spokesperson for ACPO told the Guardian in 2011 that:[62]

- "Deploying undercover officers into the protest movement was not disproportionate to the risk posed. There are many people who have got perfectly legitimate concerns about any numbers of issues about which they may wish to protest. They are perfectly decent, law-abiding people who have no intention of disrupting anybody's lives, let alone an act of criminality. Unfortunately, in the midst of some of these groups – recent history would evidence this to be true – there are a small number of people who are intent on causing harm, committing crime and on occasions disabling parts of the national critical infrastructure. That has the potential to deny utilities to hospitals, schools, businesses and your granny."

One document relating to the surveillance of environmentalists seen by the Guardian used the following justification: that the environmental campaigners could cause "severe economic loss to the United Kingdom" and an "adverse effect on the public's feeling of safety and security".[63]

It is also worth drawing attention to the Special Demonstration Squad which existed from 1968-2008, and whose purpose and officers had overlap with the domestic extremism units. The Third Herne report into the work of undercover officers targeting protest groups notes of its function: [64]

- The SDS utilised a "Statement of Purpose " that guided their operational activity and explained their role. This statement evolved over time and can best be described as an organic document. In 1998, it detailed their objective as "providing quality service in the gathering and dissemination of high grade intelligence concerning terrorism, public order events, the activities of groups involved in politically motivated crime and crime related to animal rights and environmental activity ". To achieve this, they infiltrated groups assessed as being capable of violent protest.

2018: abandonment of the term

In June 2019, the former Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, David Anderson, released a review of counter-terrorism policing issues. The report records that use of the term 'Domestic Extremism' was coming under criticism, and was considered 'manifestly deficient'.[65] It also that since 2018 UK government departments where in the process of moving from the term and a number of related ones:[66]

- Terminology

- 8.2 One recommendation committed the Home Office to considering whether the International Counter-Terrorism [ICT] and Domestic Extremism [DE] labels are still fit for purpose and if not, in consultation with the CT community, to developing new ones.

- 8.3 is an amorphous concept, stretching from groups whichcurrently pose no more than occasional public order concerns (animal rights, anti-fracking) to attack-planning by associates of the proscribed XRW terrorist organisation National Action. In practice, the "DE" most likely to reach the terrorism threshold is that promoted by the XRW, whose ideology is of white supremacy or neo-Nazism and which is to be distinguished from (but recruits from) the racist or anti-Muslim Far Right [FRW].

- 8.4 Both the ICT and the DE labels seemedto me manifestlydeficient, for the reasons given in Anderson I.28In summary:

- a)Islamist terrorism is often home-grown,just as right-wing terrorism can be international.

- b)To describe even the most threatening non-Islamist activity as "extremism" may be read as signallingthat it is taken less seriously than Islamist "terrorism".

- c)ICT stands for international counter-terrorism and should not be used to refer to a form of terrorism. More fundamentally, the categorisation of terrorism by its governing ideology might be seen as unnecessary for many (though not all) purposes, given similarities in the backgrounds and psychological profiles of both types of terrorist and in their modus operandi:a point pressed upon me by MI5’s Behavioural Analysis Unit.

- 8.5 The problem is not solved by using the phrase "Domestic Extremist Terrorism" [DET] to denote domestic extremism which reaches the threshold for terrorism. Though a convenient patch, it does not address the unsatisfactory nature of the term domestic extremism.

- 8.6 The Home Office has played a constructive role in this debate. This may be seen from the June 2018 iteration of the CONTEST strategy, which moved deliberately away from the [Domestic Extermism / International Counter-Terrorism] (DE/ICT) terminology in favour of referring to terrorism either generically or, where necessary, by reference to itsgoverning ideology (e.g. XRW). But though my criticisms of the status quo are widely understood and shared in MI5 and CTP, as well as within the Home Office, revised terminology proved more difficult to agree.

- 8.7 At a workshop in December 2018:

- a) All departments agreed to stop using the terms "Domestic Extremism", "Domestic Extremist Terrorism" and "International Counter-Terrorism".

- b) All departments agreed to move to using "terrorism" with the motivating ideology as a prefix.

Following the release of this report, The Network for Police Monitoring obtained the following statement from the Home Office,[67] which confirmed it had stopped use of the term domestic extremism.[68]

- We can confirm that the Home Office has agreed to stop using the term "domestic extremism". Work to refine and mainstream new terminology is an ongoing process as we continuously adapt to changes in threat. The Home Office remains committed to countering all forms of terrorism and extremism, regardless of ideology.

Part of the pressure to abandon the term came from difficulty in finding a legally robust definition of the word 'extremism' itself, a problem going back a number of years, affecting the government's wider counter-terrorism strategy.[69] though the John Catt case also demonstrated its problems, with the European Court of Human Rights highlighting the absence of any meaningful rules or safeguards for keeping information collected on political campaigning by the UK Government.[44]

See also

- National Domestic Extremism Unit

- National Domestic Extremism Database

- Timeline: Domestic Extremism, The Network for Police Monitoring.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Response to FOIA request made by Kevin Blowe (No: 2014030001361), Metropolitan Police Service, 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Mick Creedon, Operation Herne: Operation Trinity / Report 2 - Allegations of Peter Francis, Derbyshire Constabulary, March 2014. Though the Herne 2 report talks of the Special Branch's C Squad remit as being 'domestic extremism', this is probably a case of retrofitting the term; the lack of citing of it in Special Demonstration Squad 1998 Statement of Purpose (given in Herne) indicates it was not use in this time, though the Statement notes that animal rights activity was an SDS target.

- ↑ Undercover Research Group: Personal communication with animal rights and environmental activists corroborated by search of Parliamentary and press publications from the period. Eco-terrorism was coined by Ron Arnold in 1983 in an article for the magazine 'Reason', but did not appear to have gained traction in law enforcement until Louis Freeh, Director of the FBI started making it a priority for his agents in 1998. Nick Harding writing in the Independent in 2010 (see below) states the term was created in 1990 to describe anti-logging activists in the Pacific US. Animal Rights Extremism first appears as a phrase with public recognition in an article in the New Scientist magazine of 12 December 1998 entitled 'A martyr in the making - Britain's government shares the blame for the rise of animal rights extremism'.

- ↑ Animal Welfare - Human Rights: protecting people from animal rights extremists, Home Office, July 2004, archived at Statewatch.org, accessed 26 August 2014.

- ↑ John E. Lewis, Testimony of John E. Lewis, Deputy Assistant Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation before the Senate Judiciary Committee on 18 May 2004, regarding Animal Rights Extremism and Ecoterrorism, Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed 6 September 2014.

- ↑ ACPO welcomes 'economic damage' amendment to the Serious Organised Crime and Police Bill, ACPO press release, 31 January 2005. Archived at archive.today, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ We are aware that the Guardian article of 2009 mentions the term as being coined between 2001 and 2004, but it is not clear to us what this has been based upon, and it is not mentioned in any of the key document seen by the Undercover Research Group for the year 2004, particularly the Home Office paper of July 2004. While many later reports refer to the National Coordinator Domestic Extremism being created in 2004, this appears to be a case of retro-fitting the name to an office that was created at that time, but not formally named as such until later. However, the Undercover Research Group is open to being corrected on this should contemporaneous documents subsequently come to light or be shown to us. See also the note below regarding the 2001 Home Office publication "Extremism - Protecting People and Property", which was to be updated by NETCU as "Beyond Lawful Protest: Protecting Against Domestic Extremism", which indicates that while the word extremism was then in common parlance in 2001, 'domestic extremism' is a later development. In support of this, we note that NETCU, founded March 2004 (and prior to the NCDE / NDEU which were formed several months later, though later merged with), merely refers to 'extremism' in its name. It is also worth noting the January 2003 HMIC review of Special Branch 'A Need to Know' which refers to animal rights extremism and domestic terrorism, but not 'domestic extremism'

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Rob Evans, Paul Lewis & Matthew Taylor, How police rebranded lawful protest as 'domestic extremism', The Guardian, 25 October 2009, accessed 5 September 2014.

- ↑ Minutes of ACPO TAM meetings relating to the establishment of the NPOIU, 1998-2000, unpublished - these minutes make no use of the word 'domestic', though they do refer to animal rights and environmental extremism.

- ↑ Farewell to NETCU: A brief history of how protest movements have been targeted, Corporate Watch, 19 January 2011, accessed 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Based on discussions with animal rights, social justice and Earth First!" campaigners.

- ↑ Undercover Research Group, Re-visiting NETCU - Police Collaboration with Industry, Corporate Watch, 6 August 2014, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Paul Mobbs / The Free Range Network, Paper Q2: Britain’s Secretive Police Force, Free Range electrohippies project, April 2009, accessed 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Alan Lodge, On The Road: Criminal Justice Act (etc), DigitalJournalist.eu, accessed 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Caroline Graham, the victim of smears': Undercover policeman denies bedding a string of women during his eight years with eco-warriors, Mail Online, 17 January 2015, accessed 31 January 2015.

- ↑ BristleKRS, Email of 2 December 2014, unpublished, containing an analysis of definitions of animal rights and single issue extremism in TE-SAT reports 2007 to 2014. A list of TE-SAT reports is given on the Europol website.

- ↑ Christopher Andrew, In Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5], Penguin, 3 June 2010.

- ↑ Christopher Andrew, In Defense of the Realm: The authorised history of MI5, Penguin, 2009; also cited at MI5’s official website, MI5.gov.uk: see The Inter-War Years and The Threat of Subversion (accessed 16 August 2019).

- ↑ Donal O'Driscoll, 1969 prosecution of Ed Davoren and others, SpecialBranchFiles.uk, July 2019 (accesesd 16 August 2019).

- ↑ Transcript of cross examination of Det. Ch. Insp. Elwyn Jones in trial of Edward Michael Davoren and others, November 1969], documents taken from National Archives (DAVOREN, Edward Michael and others. Charge: Riot and assault on a constable. With photographs and plans. Session year: 1969. CRIM 1/5146) and accessed through SpecialBranchFiles.uk.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Police in £9m scheme to log 'domestic extremists', The Guardian, 25 October 2009. Accessed 26 December 2013.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Eco anarchists: A new breed of terrorist? Police forces challenged over files held on law-abiding protesters, The Guardian, 26 October 2009, accessed 5 September 2014.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Beyond Lawful Protest: Protecting Against Domestic Extremism, National Counter Terrorism Security Office, 2009, partially redacted document released in response to an FOIA request by Jason Sands.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 State Crackdown on Anti-Corporate Dissent, Corporate Watch, 2009.

- ↑ Personal communication with Max Gastone, representative of Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty during the injunction hearings.

- ↑ Aviation industry takes five million people to court, Greenpeace, 26 July 2007, accessed 20 January 2015.

- ↑ John Vidal & Dan Milmo, Catch-all Heathrow protest injunction could bar millions, The Guardian, 27 July 2007, accessed 14 January 2015.

- ↑ National MAPPA Team, MAPPA Guidance 2009 (version 3), 2009. pages 152-153.

- ↑ This model is reflected in other police documents of the same period. See for example, Avon and Somerset Police Crime Needs Assessment 2012, Office of the Avon and Somerset Police and Crime Commissioner, October 2012, para. 7.3, page 37.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Nick Harding, Eco anarchists: A new breed of terrorist?, The Independent, 18 May 2010, accessed 5 September 2014.

- ↑ National Co-ordinator Domestic Extremism, Frequently Asked Questions, Association of Chief Police Officers, ca. 2010-2011, archived by Undercover Research Group.

- ↑ Prevent Strategy, HM Government, June 2011, p.109 (Annex A: Glossary of Terms)

- ↑ A Review of National Police Units which Provide Intelligence on Criminality Associated with Protest, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, 2 February 2012.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 The full definition is given in (and attributed to the NDEU) Gordon Mills, The successes and failures of policing animal rights extremism in the UK 2004–2010, International Journal of Police Science & Management, Vol. 15, No.1, 18 February 2013.

- ↑ PREVENT Strategy (Cm 8092), Secretary of State for the Home Department June 2011, accessed 31 January 2015.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 A review of progress made against the recommendations in HMIC’s 2012 report on the national police units which provide intelligence on criminality associated with protest, Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary, June 2013.

- ↑ DCS Christopher Greany, Letter to Baroness Jenny Jones, National Domestic Extremism & Disorder Intelligence Unit, 21 March 2014, accessed 25 January 2015.

- ↑ Domestic Extremism, MI5.gov.uk, accessed 19 June 2014.

- ↑ Adi Bloom, Police tell teachers to beware of green activists in counter-terrorism talk, Times Educational Supplement, 4 September 2015 (accessed 5 September 2015).

- ↑ James Bargent, The Political Policing of Dissent in the UK, TowardFreedom.com, issue 39, 25 March 2011, accessed 20 January 2015.

- ↑ This matter was also covered extensively on campaign websites from FITWatch and NETCUWatch.

- ↑ Day 2 of the John Catt ‘domestic extremism’ Supreme Court hearing, The Network for Police Monitoring, 3 December 2014, accessed 14 January 2015.

- ↑ This is not Domestic Extermism, The Network for Police Monitoring, 1 February 2017 (accessed 16 August 2019).

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Timeline: Domestic Extremism, The Network for Police Monitoring, 2019 (accessed 16 August 2019).

- ↑ It's Time to Close Down the Police's "Domestic Extremism" Databases, The Network for Police Monitoring, 5 February 2019 (accessed 16 August 2019).

- ↑ So who exactly IS now classified as a ‘Domestic Extremist’?, The Network for Police Monitoring (NetPol), 22 April 2014, accessed 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Kevin Blowe, Secret Diary of an Olympic Domestic Extremist, The Network for Police Monitoring (NetPol), 5 February 2014, accessed 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Jenny Jones, The Met turned me into a domestic extremist – with tweets and trivia, The Guardian, 16 June 2014, accessed 12 January 2015.

- ↑ The rules of engagement: A review of the August 2011 disorders, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, 2011, accessed 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Paul Lewis & Rob Evans, Police spies: watchdog calls for safeguards over 'intrusive tactic', The Guardian, 2 February 2012. Accessed 19 January 2014.

- ↑ David Mead, The New Law of Peaceful Protest, Hart Publishing, 2010.

- ↑ Seamus Milne, We are all extremists now, The Guardian, 16 February 2009, accessed 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Seamus Milne, Spying on us doesn't protect democracy. It undermines it, The Guardian, 28 October 2009, accessed 14 November 2014.

- ↑ George Monbiot, Otter-spotting and birdwatching: the dark heart of the eco-terrorist peril, The Guardian, 23 December 2008, accessed 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Pennie Quinton, Rebranding protest as extremism, The Guardian, 30 October 2009, accessed 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Project Servator, The City of London Police, 2014, accessed 15 January 2015.

- ↑ Transcript of speech of James Brokenshire, International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, 15 March 2013, accessed 29 June 2014.

- ↑ Vikram Dodd, Chief constable warns against ‘drift towards police state’ , The Guardian, 5 December 2014, accessed 14 January 2015.

- ↑ Terrorism Act 2001, Section 1, Legislation.gov.uk, accessed 31 January 2015.

- ↑ This broad definition was criticised in July 2014 by the Government's Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, David Anderson QC. See Press Release, Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, 22 July 2014, accessed 31 January 2015.

- ↑ New definition of "terrorism" can criminalise dissent and extra-parliamentary action, Statewatch bulletin, vol. 10, no. 5 (Sept-Oct 2000), accessed 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Spying on protest groups has gone badly wrong, police chiefs say, The Guardian, 19 January 2011

- ↑ Met facing mounting crisis as activist spying operation unravels, The Guardian, 20 October 2011. Accessed 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Mick Creedon, Operation Herne: Report 3 - Special Demonstration Squad Reporting: Mentions of Sensitive Campaigns, Derbyshire Constabulary, July 2014, para. 1.7.

- ↑ Domestic extremism label is ‘manifestly deficient’ says former reviewer of terrorism laws, The Network for Police Monitoring (NetPol), 19 June 2019 (accessed 16 August 2019).

- ↑ David Anderson, 2017 Terrorist Attacks MI5 And CTP Reviews: Implementation Stock-Take (unclassified summary of conclusions, Home Office 11 June 2019.

- ↑ Victory for Netpol campaigning as Home Office confirms it has stopped using the term "domestic extremism", The Network for Police Monitoring (NetPol), 9 Aug 2019 (accessed 16 August 2019).

- ↑ J. Fanshawe, Letter to NetPol, Home Office, 30 July 2019 (accessed 16 August 2019 via NetPol.org).

- ↑ Alan Travis, Cameron terror strategy runs aground on definition of extremism, The Guardian, 3 May 2016 (accessed 16 August 2019).